The Economist gives us economists too much credit. It writes:

In... the idea that economics as a whole is discredited... backlash has gone far too far.... Economics is less a slavish creed than a prism through which to understand the world...

I would like to draw a distinction between economics as a way of thinking--the way good economists think, at least--and academic economics as a profession. Economics as a way of thinking is, I believe, still very valuable. But academic economics as a profession has proven itself to be not valuable at all in this financial crisis. As the Economist writes later on:

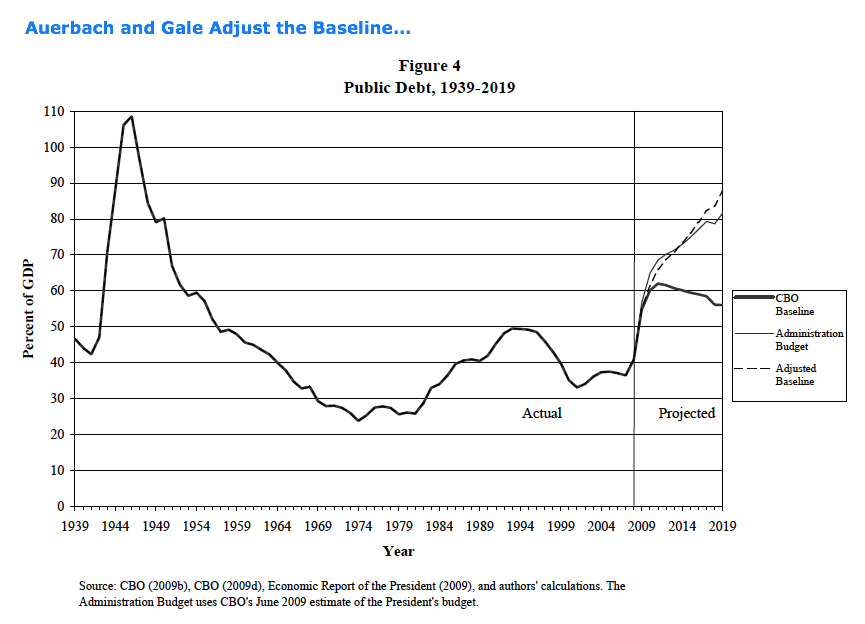

the financial crisis has blown apart the fragile consensus... [about] monetary policy... [because] in a banking crisis monetary policy works less well. With their compromise tool useless, both sides have retreated to their roots, ignoring the other camp’s ideas. Keynesians, such as Mr Krugman, have become uncritical supporters of fiscal stimulus. Purists are vocal opponents. To outsiders, the cacophony underlines the profession’s uselessness...

In my view, when you have Nobel Memorial Prize-caliber economists like Arizona State's Edward Prescott, Chicago's Robert Lucas and Eugene Fama, and Harvard's Robert Barro claiming that there are valid theoretical arguments proving that fiscal stimulus simply cannot work, not even in a deep depression--even though they cannot enunciate such theoretical arguments coherently--it is entirely fair for outsiders to conclude that academic economics as a profession is useless.

And I for the life of me cannot see what the arguments of the "purists" are. The basic quantity theory of money:

(M/P) * V(i) = Y

tells us that output depends on (a) the real money stock M/P, and (b) the velocity of money V, which (c) is an increasing function of the short-term nominal interest rate on government securities i. Fiscal policy--government deficits--change the quantity supplied of government bonds, and by supply-and-demand things that change the quantity of something change its price, and the price of government bonds is this interest rate i. It is true that Robert Barro has an argument that deficits caused by tax-law changes create offsetting changes in desired savings that neutralize the effect of increasing the supply of government bonds, but I know of no argument that claims the same for deficits caused by government-spending changes unless the goods the government buys and distributes with its spending are perfect substitutes for private consumption expenditures.

Some more context:

Economics: What went wrong with economics: OF ALL the economic bubbles that have been pricked, few have burst more spectacularly than the reputation of economics itself. A few years ago, the dismal science was being acclaimed as a way of explaining ever more forms of human behaviour, from drug-dealing to sumo-wrestling. Wall Street ransacked the best universities for game theorists and options modellers. And on the public stage, economists were seen as far more trustworthy than politicians. John McCain joked that Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, was so indispensable that if he died, the president should “prop him up and put a pair of dark glasses on him.”

In the wake of the biggest economic calamity in 80 years that reputation has taken a beating.... [T]heir pronouncements are viewed with more scepticism than before. The profession itself is suffering from guilt and rancour. In a recent lecture, Paul Krugman, winner of the Nobel prize in economics in 2008, argued that much of the past 30 years of macroeconomics was “spectacularly useless at best, and positively harmful at worst.” Barry Eichengreen, a prominent American economic historian, says the crisis has “cast into doubt much of what we thought we knew about economics.”...

[T]wo central parts of the discipline—macroeconomics and financial economics—are now, rightly, being severely re-examined.... There are three main critiques: that macro and financial economists helped cause the crisis, that they failed to spot it, and that they have no idea how to fix it. The first charge is half right. Macroeconomists, especially within central banks, were too fixated on taming inflation and too cavalier about asset bubbles. Financial economists, meanwhile, formalised theories of the efficiency of markets, fuelling the notion that markets would regulate themselves and financial innovation was always beneficial. Wall Street’s most esoteric instruments were built on these ideas.

But economists were hardly naive believers in market efficiency. Financial academics have spent much of the past 30 years poking holes in the “efficient market hypothesis”. A recent ranking of academic economists was topped by Joseph Stiglitz and Andrei Shleifer, two prominent hole-pokers. A newly prominent field, behavioural economics, concentrates on the consequences of irrational actions.... But as insights from academia arrived in the rough and tumble of Wall Street, such delicacies were put aside. And absurd assumptions were added.... The charge that most economists failed to see the crisis coming also has merit. To be sure, some warned of trouble. The likes of Robert Shiller of Yale, Nouriel Roubini of New York University and the team at the Bank for International Settlements are now famous for their prescience. But most were blindsided. And even worrywarts who felt something was amiss had no idea of how bad the consequences would be....

Macroeconomists also had a blindspot.... Their framework reflected an uneasy truce between the intellectual heirs of Keynes, who accept that economies can fall short of their potential, and purists who hold that supply must always equal demand. The models that epitomise this synthesis--the sort used in many central banks--incorporate imperfections in labour markets (“sticky” wages, for instance, which allow unemployment to rise), but make no room for such blemishes in finance. By assuming that capital markets worked perfectly, macroeconomists were largely able to ignore the economy’s financial plumbing. But models that ignored finance had little chance of spotting a calamity that stemmed from it.

What about trying to fix it? Here the financial crisis has blown apart the fragile consensus between purists and Keynesians that monetary policy was the best way to smooth the business cycle. In many countries short-term interest rates are near zero and in a banking crisis monetary policy works less well. With their compromise tool useless, both sides have retreated to their roots, ignoring the other camp’s ideas. Keynesians, such as Mr Krugman, have become uncritical supporters of fiscal stimulus. Purists are vocal opponents. To outsiders, the cacophony underlines the profession’s uselessness....

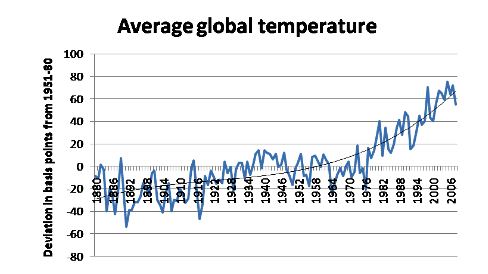

[T]here is a clear case for reinvention, especially in macroeconomics.... [A] broader change in mindset is still needed. Economists need to reach out from their specialised silos: macroeconomists must understand finance, and finance professors need to think harder about the context within which markets work. And everybody needs to work harder on understanding asset bubbles and what happens when they burst. For in the end economists are social scientists, trying to understand the real world. And the financial crisis has changed that world.

The other-worldly philosophers: [M]acroeconomists were not wholly complacent. Many of them thought the housing bubble would pop or the dollar would fall. But they did not expect the financial system to break. Even after the seizure in interbank markets in August 2007, macroeconomists misread the danger. Most were quite sanguine about the prospect of Lehman Brothers going bust in September 2008.

Nor can economists now agree on the best way to resolve the crisis. They mostly overestimated the power of routine monetary policy (ie, central-bank purchases of government bills) to restore prosperity. Some now dismiss the power of fiscal policy (ie, government sales of its securities) to do the same. Others advocate it with passionate intensity.... For Mr Krugman, we are living through a “Dark Age of macroeconomics”, in which the wisdom of the ancients has been lost.

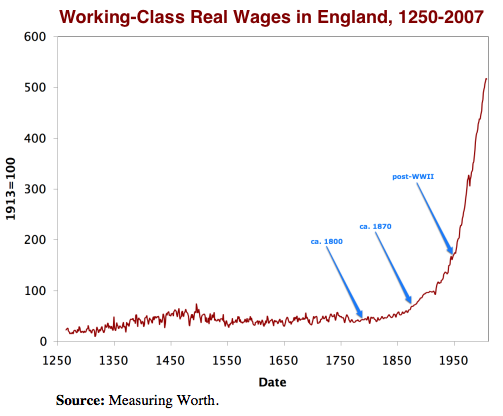

What was this wisdom, and how was it forgotten? The history of macroeconomics begins in intellectual struggle. Keynes wrote the “General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.”... [The] classical mode of thought held that full employment would prevail, because supply created its own demand... whatever people earn is either spent or saved; and whatever is saved is invested in capital projects. Nothing is hoarded, nothing lies idle. Keynes... [thought] investment was governed by the animal spirits of entrepreneurs, facing an imponderable future. The same uncertainty gave savers a reason to hoard their wealth in liquid assets, like money, rather than committing it to new capital projects. This liquidity-preference, as Keynes called it, governed the price of financial securities and hence the rate of interest. If animal spirits flagged or liquidity-preference surged, the pace of investment would falter, with no obvious market force to restore it. Demand would fall short of supply.... The Keynesian task of “demand management” outlived the Depression, becoming a routine duty of governments... aided by economic advisers.... [T]heir credibility did not survive the oil-price shocks of the 1970s. These condemned Western economies to “stagflation”, a baffling combination of unemployment and inflation, which the Keynesian consensus grasped poorly and failed to prevent.

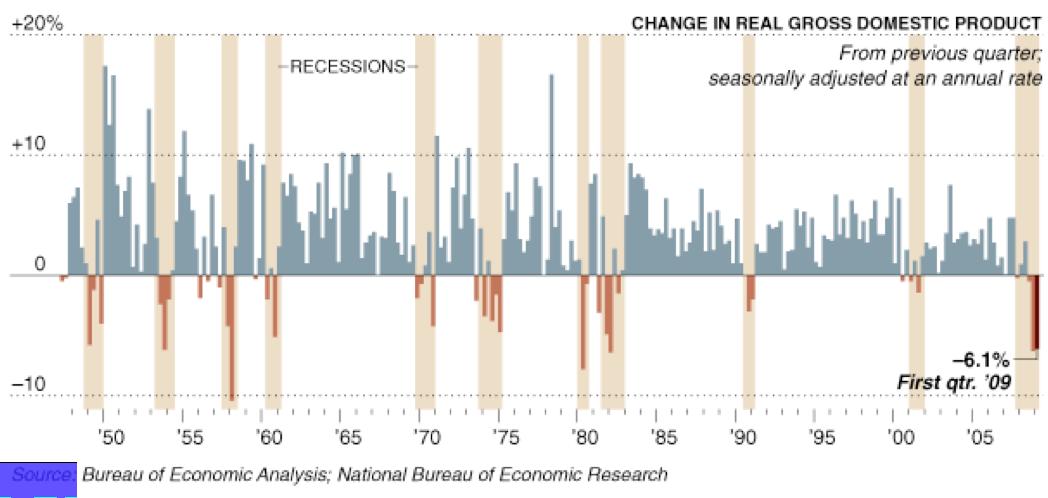

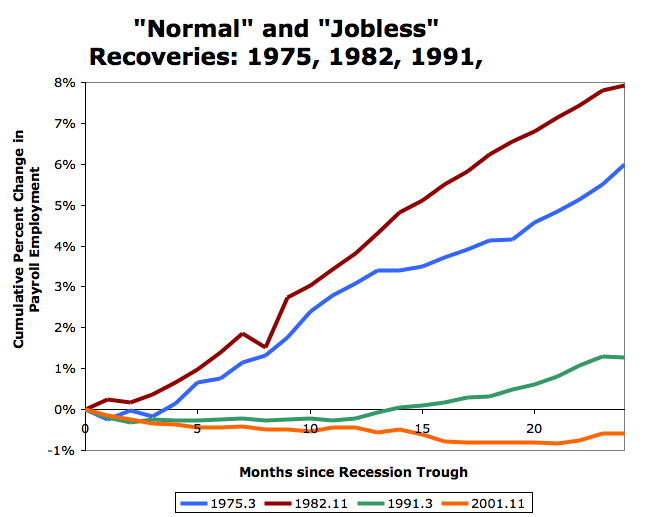

The Federal Reserve, led by Paul Volcker, eventually defeated American inflation in the early 1980s, albeit at a grievous cost to employment. But victory did not restore the intellectual peace. Macroeconomists split into two camps.... The purists... blamed stagflation on restless central bankers trying to do too much. They started from the classical assumption that markets cleared, leaving no unsold goods or unemployed workers. Efforts by policymakers to smooth the economy’s natural ups and downs did more harm than good.... [P]ragmatists... [saw] the double-digit unemployment that accompanied Mr Volcker’s assault on inflation was proof enough that markets could malfunction. Wages might fail to adjust, and prices might stick. This grit in the economic machine justified some meddling by policymakers. Mr Volcker’s recession bottomed out in 1982. Nothing like it was seen again until last year. In the intervening quarter-century of tranquillity, macroeconomics also recovered its composure. The opposing schools of thought converged.... For about a decade before the crisis, macroeconomists once again appeared to know what they were doing....

[Willem] Buiter... believes the latest academic theories had a profound influence.... He now thinks this influence was baleful... a training in modern macroeconomics was a “severe handicap” at the onset of the financial crisis, when the central bank had to “switch gears” from preserving price stability to safeguarding financial stability. Modern macroeconomists worried about the prices of goods and services, but neglected the prices of assets. This was partly because they had too much faith in financial markets....

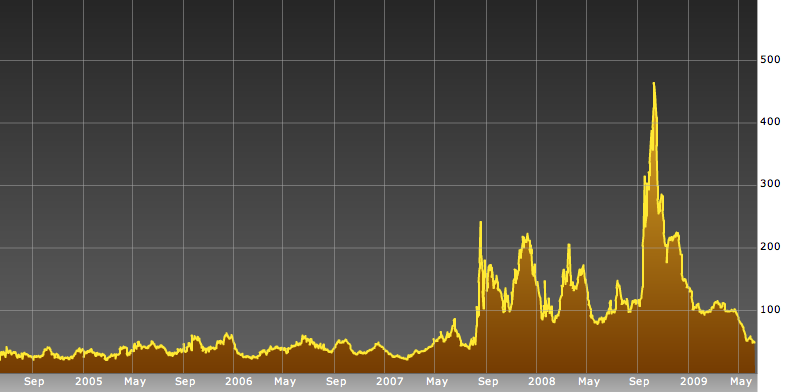

Before the crisis, many banks and shadow banks... believed they could always roll over their short-term debts or sell their mortgage-backed securities, if the need arose. The financial crisis made a mockery of both assumptions. Funds dried up, and markets thinned out. In his anatomy of the crisis Mr Brunnermeier shows how both of these constraints fed on each other, producing a “liquidity spiral”. What followed was a furious dash for cash, as investment banks sold whatever they could, commercial banks hoarded reserves and firms drew on lines of credit. Keynes would have interpreted this as an extreme outbreak of liquidity-preference.... But contemporary economics had all but forgotten the term....

In the first months of the crisis, macroeconomists reposed great faith in the powers of the Fed and other central banks.... Frederic Mishkin... presented the results of simulations from the Fed’s FRB/US model. Even if house prices fell by a fifth in the next two years, the slump would knock only 0.25% off GDP, according to his benchmark model... [because] the Fed would respond “aggressively”, by which he meant a cut in the federal funds rate of just one percentage point. He concluded that the central bank had the tools to contain the damage at a “manageable level”. Since his presentation, the Fed has cut its key rate by five percentage points to a mere 0-0.25%. Its conventional weapons have proved insufficient to the task. This has shaken economists’ faith in monetary policy. Unfortunately, they are also horribly divided about what comes next.

Mr Krugman and others advocate a bold fiscal expansion... stimulating resources that might otherwise have lain idle.... Mr Barro thinks the estimates of Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors are absurdly large. Mr Lucas calls them “schlock economics”, contrived to justify Mr Obama’s projections for the budget deficit....

Economists were deprived of earthquakes for a quarter of a century. The Great Moderation, as this period was called, was not conducive to great macroeconomics. Thanks to the seismic events of the past two years, the prestige of macroeconomists is low, but the potential of their subject is much greater. The furious rows that divide them are a blow to their credibility, but may prove to be a spur to creativity.

Financial economics: Efficiency and beyond: IN 1978 Michael Jensen, an American economist, boldly declared that “there is no other proposition in economics which has more solid empirical evidence supporting it than the efficient-markets hypothesis” (EMH). That was quite a claim. The theory’s origins went back to the beginning of the century, but it had come to prominence only a decade or so before. Eugene Fama, of the University of Chicago, defined its essence: that the price of a financial asset reflects all available information that is relevant to its value.

From that idea powerful conclusions were drawn, not least on Wall Street. If the EMH held, then markets would price financial assets broadly correctly. Deviations from equilibrium values could not last for long. If the price of a share, say, was too low, well-informed investors would buy it and make a killing. If it looked too dear, they could sell or short it and make money that way. It also followed that bubbles could not form—or, at any rate, could not last: some wise investor would spot them and pop them. And trying to beat the market was a fool’s errand for almost everyone. If the information was out there, it was already in the price.

On such ideas, and on the complex mathematics that described them, was founded the Wall Street profession of financial engineering. The engineers designed derivatives and securitisations, from simple interest-rate options to ever more intricate credit-default swaps and collateralised debt obligations. All the while, confident in the theoretical underpinnings of their inventions, they reassured any doubters that all this activity was not just making bankers rich. It was making the financial system safer and the economy healthier.

That is why many people view the financial crisis that began in 2007 as a devastating blow to the credibility not only of banks but also of the entire academic discipline of financial economics. That verdict is too simple. Granted, financial economists helped to start the bankers’ party, and some joined in with gusto. But even when the EMH still seemed fresh, economists were picking holes in it.... Academia thus moved on, even if Wall Street did not.... The EMH, to be sure, has loyal defenders. “There are models, and there are those who use the models,” says Myron Scholes, who in 1997 won the Nobel prize in economics for his part in creating the most widely used model in the finance industry—the Black-Scholes formula for pricing options. Mr Scholes thinks much of the blame for the recent woe should be pinned not on economists’ theories and models but on those on Wall Street and in the City who pushed them too far in practice.

Financial firms plugged in data that reflected a “view of the world that was far more benign than it was reasonable to take, emphasising recent inputs over more historic numbers,” says Mr Scholes. “Apparently, a lot of the models used for structured products were pretty good, but the inputs were awful.” Indeed, the vast majority of derivative contracts and securitisations have performed exactly as their models said they would. It was the exceptions that proved disastrous.... Even as financial engineers were designing all sorts of clever products on the assumption that markets were efficient, academic economists were focusing more on how markets fall short....

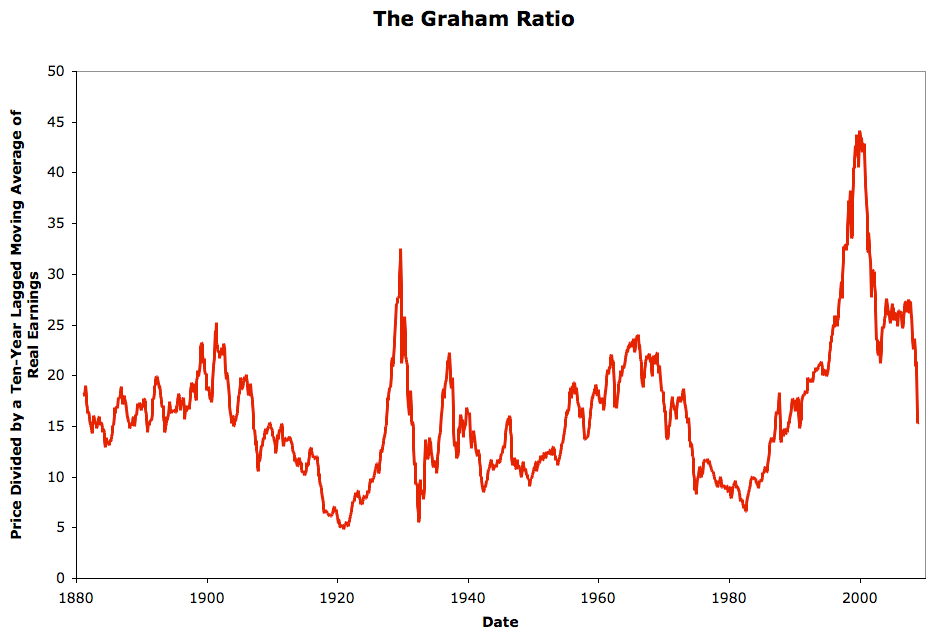

Behavioural economists were among the first to sound the alarm about trouble in the markets. Notably, Robert Shiller of Yale gave an early warning that America’s housing market was dangerously overvalued. This was his second prescient call. In the 1990s his concerns about the bubbliness of the stockmarket had prompted Alan Greenspan, then chairman of the Federal Reserve, to wonder if the heady share prices of the day were the result of investors’ “irrational exuberance”. The title of Mr Shiller’s latest book, “Animal Spirits” (written with George Akerlof, of the University of California, Berkeley), is taken from John Maynard Keynes’s description of the quirky psychological forces shaping markets. It argues that macroeconomics, too, should draw lessons from psychology. “In some ways, we behavioural economists have won by default, because we have been less arrogant,” says Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago, one of the pioneers of behavioural finance. Those who denied that prices could get out of line, or ever have bubbles, “look foolish”. Mr Scholes, however, insists that the efficient-market paradigm is not dead: “To say something has failed you have to have something to replace it, and so far we don’t have a new paradigm to replace efficient markets.” The trouble with behavioural economics, he adds, is that “it really hasn’t shown in aggregate how it affects prices.”...

One task, also of interest to macroeconomists, is to work out what central bankers should do about bubbles—now that it is plain that they do occur and can cause great damage when they burst. Not even behaviouralists such as Mr Thaler would want to see, say, the Fed trying to set prices in financial markets. He does see an opportunity, however, for governments to “lean into the wind a little more” to reduce the volatility of bubbles and crashes. For instance, when guaranteeing home loans, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, America’s giant mortgage companies, could be required to demand higher down-payments as a proportion of the purchase price, the higher house prices are relative to rents. Another priority is to get a better understanding of systemic risk, which Messrs Scholes and Thaler agree has been seriously underestimated. A lot of risk-managers in financial firms believed their risk was perfectly controlled, says Mr Scholes, “but they needed to know what everyone else was doing, to see the aggregate picture.” It turned out that everyone was doing very similar things. So when their VAR models started telling them to sell, they all did—driving prices down further and triggering further model-driven selling...

![[20090717.xls]Sheet1 Chart 1](https://swap.stanford.edu/was/20100322163935im_/http://img.skitch.com/20090717-jest7at3bgwg6uwh8k5ikm5fms.jpg)