Saudi Cartoonist Hana Hajar Sketches a Path for Female Cartoonists November 18, 2009

Posted by Malika in : Art/Theater, Comics/Cartoons , add a commentHana Hajar doesn’t consider the work she does groundbreaking–to her, transforming her thoughts into satirical drawings is simply a means to express herself.

But as Saudi Arabia’s sole prominent female cartoonist, Hajar is an undeniable trailblazer.

She has worked since 2005 for the Saudi-based English language newspaper, Arab News, where her sketches challenge everything from the role of women in Saudi society, to the war in Iraq, to the on-again, off-again status of peace talks between the Israelis and Palestinians.

Her cartoons are eye-catching, with many featuring vivid colors and over-pronounced facial features. But present in every sketch is Hajar’s signature incisive wit.

Image via Hana Hajar's website.

In one recent cartoon (pictured above), Hajar broaches the subject of the over-examination of Muslim women in today’s society. In the sketch, a Muslim woman, cloaked in a black hijab and abaya, is surrounded by a throng of hands wielding oversized magnifying glasses, all pointed at her. A fuse trails out behind the woman, as another hand reaches out to light it with a match.

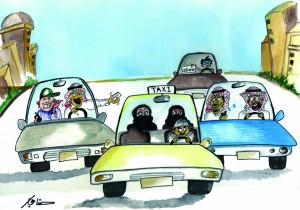

Another sketch (pictured below) depicts two women in abayas and niqab riding in a taxi, as they are bombarded on all sides by men, thrusting cell phones and phone numbers at them.

Another sketch (pictured below) depicts two women in abayas and niqab riding in a taxi, as they are bombarded on all sides by men, thrusting cell phones and phone numbers at them.

Image via Hana Hajar's website.

The cartoons are humorous, insightful and offer a perspective into Saudi society that is otherwise rarely seen. But when asked to name a favorite, Hajar says she can’t choose just one.

“All my work for me is the best. Each one represents a [different] position, and means a lot to me,” she tells MMW.

For Hajar, drawing the cartoons is the easy part. Breaking into the business was somewhat harder.

“One challenge is women’s entry into this art, which was monopolized by men for a long period of time,” she says. “But I’ve found great encouragement from my family and those who are around me.”

Growing up in Medina, Hajar’s passion for drawing began at an early age, when she found herself painting and sketching cartoons and “cynical personalities” for fun.

What was once a hobby turned into a full-time job years later, when she was offered a position at Arab News after winning a caricature competition.

Now, Hajar churns out satirical cartoons for the newspaper as well as her personal web site, HanaHajar.com, on a regular basis, all as a means to weigh in on whatever topic catches her eye.

“In the event that I want to criticize something, I find that the expression turns to drawing more than expressing it at talking,” Hajar says. “I find myself resorting to drawing.”

Though she delves into controversial topics at times, she says she hasn’t experienced any negative societal or government feedback about her work. But she admits that she censors herself at time, even before her pen hits the paper.

“I do not do anything related to religion, or sex and the limits of this – I lay [those boundaries] down for myself,” she says. “I do not draw anything contrary to my identity as a Muslim. I criticize the negative aspects only.”

The need to practice self-censorship might explain why more women haven’t yet entered the field. But Hajar says she has gotten a deluge of positive feedback from women who tell her they are happy with her work.

She says she hopes to encourage them to become comfortable with expressing their opinions through art.

“I’ll be the first cheerleader to [those] careers,” she says.

Grassroots Politics and Women’s Activism Forum in D.C. November 17, 2009

Posted by Yusra in : Culture/Society, Events, Politics , add a commentWhile in Washington, D.C., last month, I attended a forum on Muslim women’s rights titled “Women and the Politics of Change in the Middle East,” at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. It was sponsored by the Women’s Learning Partnership, an international NGO dedicated to women’s leadership and empowerment, especially in Muslim majority countries. The event was held to honor the 30th anniversary of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination (CEDAW). CEDAW is a U.N. treaty aimed at providing a universal framework for women’s rights.

The speakers (Lina Abou Habib, Mahnaz Afkhami, Wajeeha Al-Baharna, Asma Khader, Rabéa Naciri, and Azar Nafisi) all have experience leading grassroots campaigns to eliminate gender discrimination in their societies. Described by one speaker as “circumstantial feminism,” their movement focuses on getting Muslim majority governments to implement CEDAW without reservations. Many governments have ratified it without implementing articles 9 and 15—these are the most important articles because they call for equality in family and nationality laws.

In effect, their implementation would mean that a woman can travel without her husband’s approval and pass on citizenship to her children, even if she marries a non-citizen. As it stands now, the law denies citizenship to any child born to a non-national father. The Women’s Learning Partnership published first-hand testimonies of how this law affects women and families. Asma Khader, a Jordanian activist, said CEDAW was ratified in Jordan in 1998 because there was a movement, a public push for more rights. Yet even the ratification of CEDAW-which is what the women consider the minimum for women’s rights, doesn’t guarantee its implementation.

“The public—not the media—creates the buzz; it’s not the other way around,” she said. “There are success stories that go unnoticed.”

The CEDAW blog posts a few interviews, and non-profit and women’s rights organizations promote press releases and related events, yet the media isn’t too focused on the work these women do.

For example, in 2004 women mobilized, took to the streets and lobbied parliament to change the family law. In 2007, the law changed so that now Moroccan women can pass on their nationality to their children, just not to a non-Moroccan husband. Rabéa Naciri, a Moroccan activist and professor, said that resulted in more dialogue and less fear and stigmatism across the Arab world.

“We (fellow activists) learned to work in solidarity, which is something the Arab countries cannot do,” she said. “We began achieving successes and small reforms in Morocco, Algeria, Jordan and Egypt, but in general they are not well known. The media focus is on what isn’t working.”

As each of the women described their experience lobbying and organizing at the local and then international level, they reiterated Naciri’s claim that the media isn’t rushing to cover their positive stories.

All the speakers said while the push for change in family law mostly affects women, it should also include men.

Wajeeha Al-Baharna, an activist from Bahrain said media coverage or not, by focusing on just one aspect of women’s rights (citizen rights and the nationality laws in their countries), women are able to bring attention to their status as second class citizens.

After meeting with Bahraini women, whom Al-Baharna said feel guilty for choosing non-Bahraini husbands (as if they made their children victims of the state’s constrictive law), the campaign met with official bodies—the Parliament and the Shura Council—and then tried to expand their efforts regionally in what was called the Gulf Initiative. They faced resistance from men and women, whom Al Baharna said protested without knowing what they were protesting about.

The activists met with Shia clerics and a joint committee of Sunni clerics and women’s committees. The Shia clerics insisted the law couldn’t be changed from the constitution. Now there is a family law for Sunnis that Shia sects do not follow, she said.

“Sometimes it feels like we are in a constant headlock,” said Khader. “The legislations aren’t moving because we don’t have women in leadership positions. No one is pushing our demands or guaranteeing our rights.”

The event was a way to bring attention to their struggle, and an illustration of how word-of-mouth, media, and public relations can help with their grass-roots movement campaign. Seeing four Arab women and two Iranian women from different countries and backgrounds together on stage, talking about their common identity and the role they deserve to play in their societies was a powerful statement in itself. It showed that women can mobilize and work together, and will continue to speak out until in the name of equality and fair treatment.

Naciri summed it up perfectly when she said, “As Arab women, we have in common not only the discrimination against us, but the desire to live in equality and accomplish our ambitions.”

Marketing Muslim Lifestyles and Rethinking Modesty November 16, 2009

Posted by Alicia in : Books/Magazines, Events, Merchandise/Commodities , 15commentsIf a hijab in Pucci-designed print could speak, what would it say?

I attended a seminar presented by Professor Reina Lewis on Muslim women’s lifestyle magazines last night and was faced with this bizarre question. It all started with the actual seminar itself, which showcased the latest research adventures of the fashion and design professor. Weaving together previous work that included alternative Orientalist narratives in the 19th century and queer lifestyle magazines, Lewis’ paper focused on the Muslim women’s magazines that emerged at a crucial time (post-9/11) when more positive representations of Muslims were needed in a Western public discourse that had none. And the so usual suspects were mentioned: emel, Sisters, Muslim Girl, Azizah, and an anomaly, Alef–being the only one that didn’t try hard to get a particularly Muslim lifestyle look.

Having the enviable position of fashion professor, Lewis was more interested in how women/the human form were presented the magazines, what Islamic fashion is really all about, and the advertising contained within the magazines than the content. For her, visual representation in print media of women who were getting more covered up than their mothers, grandmothers, and their non-Muslim peers was striking and counter-cultural.

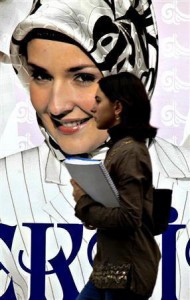

A fashion advertisement in Istanbul, Turkey.

The same way Nylon and Harper’s Bazaar are different from each other in presentation and content, Muslim lifestyle magazines set themselves apart in these ways too, but addition to that the magazines self-define or defined by others as either “Muslim” or “Islamic”. emel, Lewis said, is a “Muslim” magazine in that it reaches out to an audience of diverse backgrounds and levels of religiosity, while Azizah is more “Islamic” because it caters to a more conservative readership. It’s hard to not find these labels contentious as they could lead to a series of polemical questions, like, is emel less Islamic than say, Azizah or can a lifestyle magazine as a guide help a reader gain a more Islamic look?

Of course the latter is a silly question, but having read fashion and lifestyle magazines myself before I’d say that there is a level of self-identification in (a few of) the models and the “I am what I buy” ethos that is much invested in brand advertising today. And so for attaining the trendy or at least up-to-date Muslimah look, one only need to look at what other people are wearing, and simply flick through magazines for reference.

During the Q & A session, someone from Saudi Arabia had asked a thought-provoking question about the real purpose of fashion in faith-based women’s magazines. It was a question that I had pondered over a long time ago when I decided on two things: to not be a follower of fashion and not to wear the hijab. The question goes something like this, “If fashion is about self-expression and to a large extent ‘being noticed’, how does Islamic dressing and the fickle world of fashion reconcile with the concept of modesty and inconspicuousness?” I remember the days when I had to wear the hijab in college and becoming the object of male attention which made me uncomfortable. Without the hijab, I found to my relief that the unwanted attention seemed to have lessened, but this had nothing to do with how much skin I was showing with or without the hijab, rather the headscarf became a marker of what good young Muslim men found attractive. This was when I learned that the hijab had more complex meanings.

This brings me back to the rhetorical Pucci headscarf and what modesty means to different Muslim women. In addition to being a symbol of devotion, modesty, and cultural identity, the hijab today has taken an extra meaning, one that fits nicely with the global consumer culture and current trends. The hijab as represented even in the most conservative Islamic women’s magazines often doubles up as a fashion accessory.

Not to sound overly fussy, but isn’t being fashionable attention-grabbing and hence immodest? I need to mention again that I am not into lifestyle magazines, fashion, and do not wear the headscarf, so I’m perhaps the least equipped person to explain whether Islamic fashion is modest or not. At the same time I think my assumptions that modesty clashes with fashion is probably unfounded, too.

What are your thoughts?

Friday Links — Novemer 13, 2009 November 13, 2009

Posted by Fatemeh in : Links , 1 comment so far- Saudi women participate in a black ribbon campaign to lobby against guardianship.

- Aicha Ech Channa wins the Opus Prize for helping unwed mothers despite Moroccan society’s condemnation.

- emel magazine highlights Britain’s Sure Start program and profiles a woman who volunteers for it.

- Oxford starts a scholarship in memory of Neda Agha Soltan.

- The Arab Women Organization has organized a media training session to implement an “information strategy for Arab women designed to present a true and balanced image of Arab women and their active contribution to the comprehensive and sustainable development.”

- A woman was sentenced to two years in a British prison after being found with documents relating to weapons construction.

- Muslim women in Varanasi, India condemn a fatwa against a nationalist song.

- A Philadelphia woman talks a gunman into turning himself in.

- More on Shadi Sadr’s human rights award.

- Fairuz magazine profiles Leila Ben Ali.

- The man who murdered Marwa El Sherbini has been sentenced to life in jail. Via TalkIslam. More from IslamOnline and The Guardian.

- The 2009 Global Gap Gender Report shows that Saudi women’s place in society is up, while Syrian women’s place has dropped.

- emel magazine reviews An Ode to My Sisters.

- Gaza holds a women’s film festival.

- Iraq’s first female students of the country’s police academy graduate.

- CNN talks about sex and divorce in Egypt.

- The U.A.E. intends to appoint the world’s first state-sanctioned female muftis next year. Via New Statesman.

- Brunei is sending a woman to be part of a Kaspersky Lab Commonwealth Antarctic Expedition collaboration.

- The Star profiles a sports hijab designer.

- The Organization of Islamic Conference will not interfere in Turkey’s headscarf issue.

- A Spanish high school shut down a planned protest against the fact that headscarves can be worn, but not hats.

- A Muslim women in Mehbullahpur, India, helps get ghettoized Muslim women and their families on their feet.

- Again with Sarkozy and the burqa ban!

- Muslim women in Gloucestershire, U.K. take community cycling lessons.

- A one-day conference in Pittsburg this week will look at health care issues and women’s role in Muslim families.

- Diwan profiles poet Nimah Nawwab.

- Saudi Arabia’s Justice Minister said that women are well on their way to becoming practicing lawyers in the country–representing female clients only, that is.

- According to The National, almost one third of the women who approach the emirate’s shelter for victims of domestic abuse are Emirati, but there are many more who do not come forward.

- Refugee women in the U.K. are at high risk for forced marriages.

- Barnard College and Glamour teamed up to honor the One Million Signatures Campaign.

- Women flocked to see the first female football game in the West Bank.

- emel profiles a blind Muslim woman and her guide dog.

Supporting Mothers: Aicha Ech Channa’s Opus Prize November 12, 2009

Posted by Krista in : News , 3commentsWell, readers, I’m feeling an interesting combination of exhausted and giddy at the moment after my graduation today, which doesn’t lend itself well to my usual snarky media critique. I won’t even try. Instead, I’m going to point you in the direction of this article (mentioned recently on MMW’s Twitter feed), so that you can feel all happy and warm and fuzzy, too.

Half the reason for this is because the picture accompanying the story is just so darn cute (masha’Allah):

Aicha Ech Channa. Photo via Thomas Whisenand, for the Opus Project

But it’s also a cool story about a Moroccan woman, Aicha Ech Channa, who has recently been given an award for her work with unwed mothers:

She is the first Muslim to win the Opus award. The annual humanitarian award from the Minnetonka-based Opus Prize Foundation goes to unsung heroes for their faith-based acts of compassion.

[...]

Ech Channa, 68, is the founder and president of the Association for Women’s Solidarity. In the 1980s, she was working for the Moroccan Ministry of Social Affairs, where unwed mothers came seeking help, even though little help was available. Under Islamic law, the women were considered prostitutes, and many had their babies taken away over their objections.

Considering that unacceptable, Ech Channa launched her program in 1985. It offers women legal counseling, job training and medical and psychological support with a goal of making them self-sufficient so they can raise their children.

Having done some volunteer work with a community of young mothers, I appreciate projects that offer a combination of forms of support that these women might need. I also think it’s cool that although the article makes repeated (excessive) mention of the people who oppose Ech Channa’s project on religious grounds, it’s also clear that she herself is “committed to her faith,” and motivated by it to do the work she’s doing, believing that “Every human being has a flame [of love] inside them that must be fanned.”

Is Women’s Empowerment as Simple as Drawing a Line? Thoughts on the Khede Kasra Campaign November 11, 2009

Posted by Eman Hashim in : Advertisements, Culture/Society , 5commentsBack in early 2008, the Hariri Foundation’s Women Empowerment Program wanted to start a national campaign addressing Lebanese society—all its classes, religions, and cultural backgrounds—with one goal: that the idea of “women’s rights” is not a prestigious cliché, but a value and a part in our daily life. So they hired Leo Burnett to do that in a low-cost way that stays away from religious issues.

In his interview with Nathalie Bontems, Bukhara Mouzannar, the executive creative director at Leo Burnett, stated: “We had to go for minimalism, something that everybody, including the less educated segment of the population, which is our core target, would understand.”

And this was it:

Using basic Arabic language rules that distinguish whether one is addressing a male or a female, the campaign uses an accent (called “kasra”, the Arabic word for the grammatical symbol added to a word to make it sound feminine) to highlight the differences in language: when one reads a male-formed word, he or she will assume it can be meant for both but it will sound masculine. Readers are asked to place kasras underneath words that are normally read as male to include themselves.

In the campaign’s big street billboards, three phrases are used: “Your responsibility”, “Your right” and “Your willpower”. Without a kasra, everyone asked to read them did so in the male form.

Urging women to take part in every aspect of life, the campaign asked each woman to know that she is one of those addressed by any word in the default form as a symbol of each and everything happening around her. By placing the kasra in words, each woman is taking her place in the audience of this word, and in turn take her place in the world.

In a very symbolic move, all Lebanese people were asked to actually draw the kasra under the words to really move the people into actually doing something about it. When I draw the sign that makes that word feminine, I will always remember the feminine share in each and every word afterwards. In another words, I will always remember that I am one of those people meant by each and every word because I exist!

As mentioned in the video, interaction with the campaign was massive, including both men and women and hitting different parts of the society. Several different TV presenters in Lebanon wore the Kasra symbol as a symbol of their support and participation in the campaign.

While so many articles and bloggers applauded the initiative, others questioned the approach. Tracey McCormick, in her article “Rock the Kasra“, asked a question for those who believe language can be a way of changing ideologies:

How could these intellectuals, these doctors of belaboring, put so much emphasis on a single word? Did they really think they could effect change with one linguistic meme?

…

At one point you really need to ask yourself, “Can changing the language change a person’s perception?”

But at the end of her article, she considered the “putting the kasra” action a step toward slimming the gap between the words and the ideas by making every person actually change the language by his or her own hands.

The campaign started to get more attention from Arabic, English, and French presses in Lebanon. And then awards came pouring in, including the Mena Cristal Awards, Cannes’ Gold Lion, and The Golden Drum Awards.

But where are everyday Lebanese people in all this? The campaign obviously grabbed lots of international and official attention, but what about the normal Lebanese citizen? There are so many articles and interviews about the awards, but none speaking to Lebanese themselves. Many Leo Burnett staff members were interviewed, but the Hariri Foundation is nowhere to be found. Aside from Lebanese newspaper articles, there seems to be very little reaction from Lebanese society.

And as much as this campaign has succeeded in gaining international attention and awards, the questions about its method are still left unanswered: can language actually change how people think? Can linguistic differences affect how someone feels about herself, her life, and her role in it?

This is what Khede Kasra has set out to do. Only time will tell whether the campaign has succeeded at doing more than winning awards.

Politics as Usual: Press TV Covers Afghanistan November 10, 2009

Posted by Safiya Outlines in : Politics, Television , 4commentsA substantial amount of the media critiqued at MMW involves Muslim women being viewed as part of a minority. As flawed as it often is, one wonders if the media in Muslim majority countries may make fewer missteps. Moving on from that possibility, what about countries which have an interpretation of Islam as their legal and constitutional basis?

With satellite and online media rapidly expanding, it is possible to explore this theory. Press TV is an English language new channel, heavily guided/funded by the Iranian state. It focuses mainly on news and documentaries.

One of these documentaries is Maybe Tomorrow, which focuses on life in Afghanistan, both before and after the Taliban. The documentary is 25 minutes long and features interviews with two Afghan politicans: the Presidential candidate Ramazan Bashardost and Fuzie Koffie, a member of parliament (MP).

Bashardost was interviewed at length about rebuilding Afghanistan and how he feels the NGOs have wasted much of the supposed aid. He is seen greeting both members of the public and fellow politicians, while elaborating on his views.

Koffie is first seen in classroom where Afghan women are learning how to use computers. The power cuts and the teacher states that the electricity cuts out several times a day.

While we eventually see Koffie meet with constituents and make phone calls, she is not questioned in as much detail as Bashardost. When asked about being a female MP, she explains that she feels very proud. Then she describes a dilemma common to many Muslim women: that while she is again proud of her traditional values, including her brothers’ protectiveness, she dislikes it when that protectiveness becomes stifling, as it clashes with her views as a feminist.

Sadly, that is as in depth as the documentary gets with Koffie. This seems such a frustratingly missed opportunity and a shoddy attempt at tackling serious issues. Especially as she could give so much insight into the Afghan women’s struggle in reconciling tradition with modernity, with all the complexities that entails.

The main issue was the stark difference in treatment of the two MPs by the documentary makers. Bashardost was allowed to talk at length, was always shown in a professional context and was asked strictly about political matters. Koffie, on the other hand was shown equally at home and at work, but was only allowed short sound bite answers to specific questions, most of which focused on her being a woman and one on who she would vote for.

Afghan women typify the Muslim women experience of being spoken about endlessly, but so rarely being spoken to. When Muslim-owned media is as adept in silencing us as it’s non-Muslim counterparts, one wonders when exactly it will be our time to speak.

Stay tuned! November 6, 2009

Posted by Fatemeh in : Uncategorized , add a commentSalam waleykum, readers!

We’ve had a reduced posting schedule this week because I’ve been swamped with traveling and other things. But don’t worry: next week, we’ll be back to our regular schedule: same MMW time, same MMW channel!

Saudi Female Journalist Becomes LBC’s Scapegoat November 4, 2009

Posted by Guest Contributor in : News, Television , 8commentsThis post was written by Sabria Jawhar, and originally appeared at the Saudi Gazette and at her personal blog.

Something got lost in all the outrage last week over the conviction and lashing sentence of the 22-year-old Saudi woman journalist, Rozanna Yami. Something got lost in all the outrage last week over the conviction and lashing sentence of the 22-year-old Saudi woman journalist who worked for the Lebanese Broadcasting Corp (LBC). What exactly is the LBC doing to support their journalist?

Rozanna Yami. Image via Saeed Shamaa/EPA.

The answer is absolutely nothing.

According to a Reuters report this week, the young woman had nothing to do with the Bold Red Line broadcast segment in which a Saudi man bragged about his sexual conquests. The man was sentenced to five years in jail and lashings, but the woman journalist only worked as a “fixer,” someone who arranges interviews for foreign media. She apparently had nothing to do with the segment involving the braggart. Her crime apparently is that she worked for the LBC, which was not licensed to operate in Saudi Arabia.

Let’s set aside the idiocy that the Saudi government did not know that the LBC was not licensed. Let’s focus on the conduct of the LBC. The Lebanese were kicked out of the country, so they suffered a bit for their actions. But they also couldn’t get out of Saudi Arabia fast enough, leaving behind a vulnerable employee who proved to be the LBC’s scapegoat for their poor behavior. King Abdullah this week pardoned the woman, but she still must face a tribunal before the Saudi Ministry of Culture and Information.

A year ago the LBC approached me and offered a job that eventually went to this young Saudi journalist. I spoke over the phone with their producers and a presenter. It quickly became clear that the LBC was not interested in Saudi news, but creating tabloid headlines.

Among the topics the LBC was eager to cover were strange sexual practices, voodoo and black magic, especially black magic practiced on wayward husbands. Runaway girls, marriages of convenience and spinsterhood were other topics the LBC wanted to present. The LBC was clearly interested in the sensational aspects of Saudi culture, taboo subjects that are not topics of conversation. Yet the LBC seemed unmoved that these stories would perpetuate Saudi stereotypes in a period in which Saudis are under attack for their cultural and religious differences.

Part of my responsibility as a Saudi journalist is that if wrongdoing is exposed or taboo subjects are addressed, solutions must be provided in these stories. Perhaps more important is the safety and well-being of the people we interview. It’s likely that Saudis who participate in media interviews on sensitive subjects will face consequences for their actions.

It’s one thing to interview a Saudi woman who chooses to remain unmarried to pursue a career. It’s another for a young woman forced into spinsterhood by her father who wants her income. If such a woman gave an interview, she would have to answer to her family. What kind of support would the LBC provide for the girl if she was thrown out of the house? I think none. No two better examples of abandonment can be found than the sex braggart and the Saudi journalist.

During our discussion about my role in their Bold Red Line series, the LBC producers were cavalier, if not dismissive, about my concerns over the consequences of these kinds of interviews. When the discussion turned to me being hired as a producer, I thought that I could control editorial content. But the answer was no. Editorial control came from Beirut.

It became apparent that if I were to arrange the interviews, it would become my responsibility to see that the interviewees did not suffer any consequences for their frank talk. But that is an extremely risky task without the support of the employer.

I recognized the LBC was not prepared to offer any support after a broadcast to its Saudi employees or the interview subjects. Their desire to present sensitive Saudi issues as tabloid fodder was not much different than Western media parachuting into Riyadh for two days to do a story on how the abaya and niqab are oppressive to women. It makes for interesting television and boosts ratings, but it leaves a lot of pain and humiliation in its wake.

I rejected the LBC’s offer. Their attitude toward Saudi Arabia was insincere and cynical. I could not see how the Bold Red Line series would benefit or shed any light on Saudi culture, other than presenting Saudis as parodies of themselves.

It didn’t occur to me until this young Saudi female journalist stood trial for the LBC’s negligence that the LBC’s producers would prey on someone who is young, perhaps naïve, and eager to advance her journalism career.

Now this young woman is suffering for the sins of the LBC, which has stood by mute. They offered no lawyer and no statement of condemnation for her treatment by the Saudi courts. LBC should be an embarrassment to Middle East journalists. At a time when Arab journalists are seeking to be taken seriously as professionals and attempt to adhere to an ethical standard, the LBC’s cowardice illustrates just how little progress we have made.

Sexiness for Everyone (even Muslims) November 2, 2009

Posted by Krista in : Advertisements , 6commentsLiaison Dangereuse, a German online lingerie store, recently released a new video advertisement. With Arabic-sounding music in the background, a woman is shown getting out of the shower (we can see, from the back, that she has no clothes on), putting on her make-up, then walking (wearing nothing but high heels–to each her own, I suppose) to her dresser, where she puts on her underwear, bra and socks, all the while looking at herself in the mirror. Last (anyone see where this is going yet?), she puts on a burqa. The final scene is of her face at a window, with this phrase showing up: “Sexiness for everyone. Everywhere.”

Warning: This video contains explicit images.

Some have suggested the add may be empowering (and, according to this one, especially empowering for “women in certain desert nations.” I’m not even going to go there.) As Dodai of Jezebel writes, with some reservations, “You could view the woman in the commercial as confident and self-assured.” True. Furthermore, unlike the major impression given in a different discussion about Muslim women’s lingerie, the confidence and “sexiness” that this woman displays are seemingly for her alone; she is not wearing this clothing simply to be attractive to a man. We can perhaps even take from this an empowering message for everyone, the idea that we can all feel sexy, if we so choose, without anyone else having to see us or to think of us as sexy.

But.

All of that said, the empowerment message doesn’t really hold up. There is a whole lot of irony that these images are made so explicit in a public advertisement, given that they are supposedly valuing a sexuality that isn’t overtly expressed on the outside. The public spectacle of an apparent private moment of expressing confidence in one’s own body obviously negates the privacy of that moment.

All the other arguments aside, it seems therefore pretty hard to argue that this ad is something positive or empowering, if it would probably be rather offensive and disrespectful to most of those who would presumably be the ones it attempts to empower.

And, although the message seems to be about personal sexuality, there’s definitely still a strong male gaze and sense of objectification (and exoticization) at play, and it’s pretty unlikely that this was irrelevant in the construction of the video. One online response to the advertisement referred to its protagonist as an “exotic hottie” that the audience (and I’m guessing this is referring specifically to the heterosexual male component of the audience) is “treated to.” Another says:

Welcome to Friday, gentlemen, a day when your mind drifts to thinking about risking surfing porn from your work desk. Well, here’s a video appetizer, via Berlin ad agency glow GmbH, for German online lingerie store Liaison Dangereuse. Tagline: Sexiness for everyone. Everywhere.” It’s got brief bare butt, and an ending twist that’ll make you Catholics feel a little guilty.

So yeah, sexiness is “everywhere” and “for everyone,” ready to be served up as your pre-weekend porn appetizer. Great.

More important is the bigger context in which this ad appears – the fascination about Muslim women’s bodies, and the curiosity about what’s “behind the veil.” In fact, this isn’t even the first time that Muslim women’s lingerie has been discussed on MMW; apparently, it’s a hot topic. Why? As I’ve said previously,

What could be a more titillating image than that of a Muslim women (presumably veiled, of course) picking out something sexy to wear when in her private harem home? It might as well be proof of the Orientalist fantasy of the seductive, exotic temptress that exists within every Muslim woman, if only we could unveil her. (*shudder*)

Sadly, this isn’t even remotely new; see, for example, the kind of work that’s been done on the behind-the-veil/into-the-harem writing of colonial times. Meyda Yegenoglu’s Colonial Fantasies or Malek Alloula’s work (summarised fairly well here) are interesting places to start. The obsession with the veil (and with what’s under it) has a long history, and one that is intricately connected to colonization, racism, and sexism. This advertisement does nothing to disrupt that history, leaving us with a character who is still being objectified, as a Muslim and as a woman, even when this is under the guise of female empowerment.