Steven Strogatz on math, from basic to baffling.

Steven Strogatz on math, from basic to baffling.

Tags:

There’s a narrative line that runs through arithmetic, but many of us missed it in the haze of long division and common denominators. It’s the story of the quest for ever-more versatile numbers.

The “natural numbers” 1, 2, 3 and so on are good enough if all we want to do is count, add and multiply. But once we ask how much remains when everything is taken away, we are forced to create a new kind of number — zero — and since debts can be owed, we need negative numbers too. This enlarged universe of numbers called “integers” is every bit as self-contained as the natural numbers, but much more powerful because it embraces subtraction as well.

More in This Series

- From Fish to Infinity (Jan. 31, 2010)

- Rock Groups (Feb. 7, 2010)

- The Enemy of My Enemy (Feb. 14, 2010)

A new crisis comes when we try to work out the mathematics of sharing. Dividing a whole number evenly is not always possible … unless we expand the universe once more, now by inventing fractions. These are ratios of integers — hence their technical name, “rational numbers.” Sadly, this is the place where many students hit the mathematical wall.

There are many confusing things about division and its consequences, but perhaps the most maddening is that there are so many different ways to describe a part of a whole.

If you cut a chocolate layer cake right down the middle into two equal pieces, you could certainly say that each piece is “half” the cake. Or you might express the same idea with the fraction 1/2, meaning 1 of 2 equal pieces. (When you write it this way, the slash between the 1 and the 2 is a visual reminder that something is being sliced.) A third way is to say each piece is 50 percent of the whole, meaning literally 50 parts out of 100. As if that weren’t enough, you could also invoke decimal notation and describe each piece as 0.5 of the entire cake.

This profusion of choices may be partly to blame for the bewilderment many of us feel when confronted with fractions, percentages and decimals. A vivid example appears in the movie “My Left Foot,” the true story of the Irish writer, painter and poet Christy Brown. Born into a large working-class family, he suffered from cerebral palsy that made it almost impossible for him to speak or control any of his limbs, except his left foot. As a boy he was often dismissed as mentally disabled, especially by his father, who resented him and treated him cruelly.

A pivotal scene in the movie takes place around the kitchen table. One of Christy’s older sisters is quietly doing her math homework, seated next to her father, while Christy, as usual, is shunted off in the corner of the room, twisted in his chair. His sister breaks the silence: “What’s 25 percent of a quarter?” she asks. Father mulls it over. “Twenty-five percent of a quarter? Uhhh … That’s a stupid question, eh? I mean, 25 percent is a quarter. You can’t have a quarter of a quarter.” Sister responds, “You can. Can’t you, Christy?” Father: “Ha! What would he know?”

Writhing, Christy struggles to pick up a piece of chalk with his left foot. Positioning it over a slate on the floor, he manages to scrawl a 1, then a slash, then something unrecognizable. It’s the number 16, but the 6 comes out backwards. Frustrated, he erases the 6 with his heel and tries again, but this time the chalk moves too far, crossing through the 6, rendering it indecipherable. “That’s only a nervous squiggle,” snorts his father, turning away. Christy closes his eyes and slumps back, exhausted.

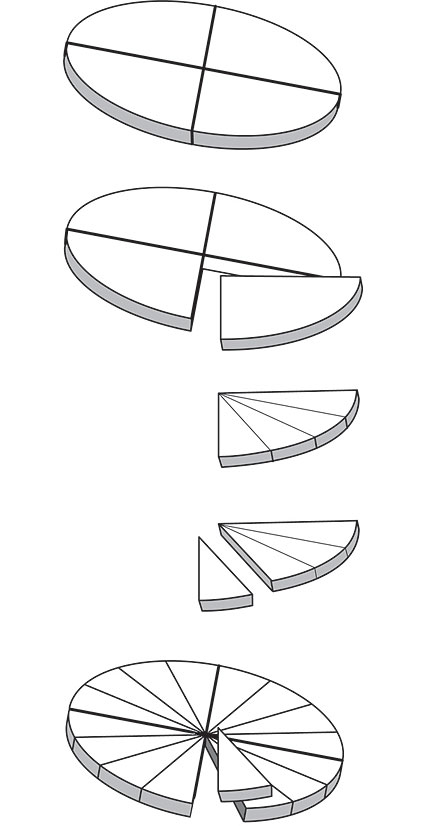

Aside from the dramatic power of the scene, what’s striking is the father’s conceptual rigidity. What makes him insist you can’t have a quarter of a quarter? Maybe he thinks you can only take a quarter of a whole or of something made of four equal parts. But what he fails to realize is that everything is made of four equal parts. In the case of something that’s already a quarter, its four equal parts look like this:

Since 16 of these thin slices make the original whole, each slice is 1/16 of the whole — the answer Christy was trying to scratch out.

A version of the same kind of mental rigidity, updated for the digital age, made the rounds on the Internet a few years ago when a frustrated customer named George Vaccaro recorded and posted his phone conversation with two service representatives at Verizon Wireless. Vaccaro’s complaint was that he’d been quoted a data usage rate of .002 cents per kilobyte, but his bill showed he’d been charged .002 dollars per kilobyte, a hundredfold higher rate. The ensuing conversation climbed to the top 50 in YouTube’s comedy section.

About halfway through the recording, a highlight occurs in the exchange between Vaccaro and Andrea, the Verizon floor manager:

V: “Do you recognize that there’s a difference between one dollar and one cent?”

A: “Definitely.”

V: “Do you recognize there’s a difference between half a dollar and half a cent?”

A: “Definitely.”

V: “Then, do you therefore recognize there’s a difference between .002 dollars and .002 cents?”

A: “No.”

V: “No?”

A: “I mean there’s … there’s no .002 dollars.”

A few moments later Andrea says, “Obviously a dollar is 1.00, right? So what would .002 dollars look like? I’ve never heard of .002 dollars… It’s just not a full cent.”

The challenge of converting between dollars and cents is only part of the problem for Andrea. The real barrier is her inability to envision a portion of either.

From first-hand experience I can tell you what it’s like to be mystified by decimals. In 8th grade Ms. Stanton began teaching us how to convert a fraction into a decimal. Using long division we found that some fractions give decimals that terminate in all zeroes. For example, 1/4 = .2500…, which can be rewritten as .25, since all those zeroes amount to nothing. Other fractions give decimals that eventually repeat, like

5/6 = .8333…

My favorite was 1/7, whose decimal counterpart repeats every six digits:

1/7 = .142857142857….

The bafflement began when Ms. Stanton pointed out that if you triple both sides of the simple equation

1/3 = .3333…,

you’re forced to conclude that 1 must equal .9999…

At the time I protested that they couldn’t be equal. No matter how many 9’s she wrote, I could write just as many 0’s in 1.0000… and then if we subtracted her number from mine, there would be a teeny bit left over, something like .0000…01.

Like Christy’s father and the Verizon service reps, my gut couldn’t accept something that had just been proven to me. I saw it but refused to believe it. (This might remind you of some people you know.)

But it gets worse — or better, if you like to feel your neurons sizzle. Back in Ms. Stanton’s class, what stopped us from looking at decimals that neither terminate nor repeat periodically? It’s easy to cook up such stomach-churners. Here’s an example:

0.12122122212222…

By design, the blocks of 2 get progressively longer as we move to the right. There’s no way to express this decimal as a fraction. Fractions always yield decimals that terminate or eventually repeat periodically — that can be proven — and since this decimal does neither, it can’t be equal to the ratio of any whole numbers. It’s “irrational.”

Given how contrived this decimal is, you might suppose irrationality is rare. On the contrary, it is typical. In a certain sense that can be made precise, almost all decimals are irrational. And their digits look statistically random.

Once you accept these astonishing facts, everything turns topsy-turvy. Whole numbers and fractions, so beloved and familiar, now appear scarce and exotic. And that innocuous number line pinned to the molding of your grade school classroom? No one ever told you, but it’s chaos up there.

NOTES:

George Vaccaro’s blog provides the exasperating details of his encounters with Verizon.

The transcript of his conversation with customer service is available here.

For readers who may still find it hard to accept that 1 = .9999…, the argument that eventually convinced me was this. They must be equal, because there’s no room for any other decimal to fit between them. (Whereas if two decimals are unequal, their average is between them, as are infinitely many other decimals.)

The amazing properties of irrational numbers are discussed at a higher mathematical level here.

The sense in which their digits are random is clarified here.

Thanks to Carole Schiffman for her comments and suggestions, and to Margaret Nelson for preparing the illustrations.