What Did I Say?

March 18, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

The History of the Honey Trap

March 18, 2010

MI5 is worried about sex. In a 14-page document distributed last year to hundreds of British banks, businesses, and financial institutions, titled “The Threat from Chinese Espionage,” the famed British security service described a wide-ranging Chinese effort to blackmail Western businesspeople over sexual relationships. The document, as the London Times reported in January, explicitly warns that Chinese intelligence services are trying to cultivate “long-term relationships” and have been known to “exploit vulnerabilities such as sexual relationships … to pressurise individuals to co-operate with them.”

This latest report on Chinese corporate espionage tactics is only the most recent installment in a long and sordid history of spies and sex. For millennia, spymasters of all sorts have trained their spies to use the amorous arts to obtain secret information.

The trade name for this type of spying is the “honey trap.” And it turns out that both men and women are equally adept at setting one — and equally vulnerable to tumbling in. Spies use sex, intelligence, and the thrill of a secret life as bait. Cleverness, training, character, and patriotism are often no defense against a well-set honey trap. And as in normal life, no planning can take into account that a romance begun in deceit might actually turn into a genuine, passionate affair. In fact, when an East German honey trap was exposed in 1997, one of the women involved refused to believe she had been deceived, even when presented with the evidence. “No, that’s not true,” she insisted. “He really loved me.”

Those who aim to perfect the art of the honey trap in the future, as well as those who seek to insulate themselves, would do well to learn from honey trap history. Of course, there are far too many stories — too many dramas, too many rumpled bedsheets, rattled spouses, purloined letters, and ruined lives — to do that history justice here. Yet one could begin with five famous stories and the lessons they offer for honey-trappers, and honey-trappees, everywhere…

The Arab Tomorrow

March 18, 2010

The Arab world today is ruled by contradiction. Turmoil and stagnation prevail, as colossal wealth and hypermodern cities collide with mass illiteracy and rage-filled imams. In this new diversity may lie disaster, or the makings of a better Arab future.

October 6, 1981, was meant to be a day of celebration in Egypt. It marked the anniversary of Egypt’s grandest moment of victory in three Arab-Israeli conflicts, when the country’s underdog army thrust across the Suez Canal in the opening days of the 1973 Yom Kippur War and sent Israeli troops reeling in retreat. On a cool, cloudless morning, the Cairo stadium was packed with Egyptian families that had come to see the military strut its hardware. On the reviewing stand, President Anwar el-Sadat, the war’s architect, watched with satisfaction as men and machines paraded before him. I was nearby, a newly arrived foreign correspondent.

Suddenly, one of the army trucks halted directly in front of the reviewing stand just as six Mirage jets roared overhead in an acrobatic performance, painting the sky with long trails of red, yellow, purple, and green smoke. Sadat stood up, apparently preparing to exchange salutes with yet another contingent of Egyptian troops. He made himself a perfect target for four Islamist assassins who jumped from the truck, stormed the podium, and riddled his body with bullets.

As the killers continued for what seemed an eternity to spray the stand with their deadly fire, I considered for an instant whether to hit the ground and risk being trampled to death by panicked spectators or remain afoot and risk taking a stray bullet. Instinct told me to stay on my feet, and my sense of journalistic duty impelled me to go find out whether Sadat was alive or dead.

I wove my way through the fleeing crowd and managed to reach the podium. It was pandemonium. Wild-eyed Egyptian security men were running every which way, trying to apprehend the assassins and attend to the scores of foreign and local dignitaries present, seven of whom lay dead or dying. The utter chaos allowed me to get close enough to witness another unforgettable scene: Vice President Hosni Mubarak emerging from beneath a pile of chairs security men had thrown helter-skelter over him for protection. He was brushing dirt off his peaked military cap, which had been pierced by a bullet.

Mubarak, lucky to be alive, pulled himself together admirably that day to take over leadership of the shaken Nile River nation. But Egypt and the rest of the Arab world would never be the same. For centuries, Egypt had prided itself on being the center of that world. Seat of a 5,000-year-old civilization that at times had thought of itself as umm idduniya, “mother of the world, ” it was the most populous and economically and militarily powerful Arab state, a center of culture and learning that supplied physicians, imams, and technical experts to other Arab nations. Under Sadat and his predecessor, the pan-Arab hero Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918–70), Egypt had reasserted its primacy as the Arabs broke free of colonial rule after World War II and entered an era of soaring hopes. Sadat had even begun some pioneering reforms—allowing opposition political parties, implementing market-oriented economic changes—that might have rippled through the Arab world had he lived. Though many reviled him for signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, Egypt remained the most dynamic force in Arab affairs.

Mubarak’s accession would bring an abrupt end to Egypt’s preeminence. Cautious and unimaginative, the former air force commander has never in his 29-year reign come close to filling the shoes of his predecessors. Afflicted by health problems, he will turn 82 in May and is not expected to reign much longer. Cairo is awash with speculation about who will replace him. Its discontented intelligentsia is debating intensely whether Egypt any longer has the wherewithal, or vision, to shape Arab policies toward an immovable Israel, a belligerent Iran, fractious Palestinians, or an imposing America, much less grapple with the Islamist challenge to secular governments.

During the Mubarak years, other voices and centers have arisen, particularly on the western shores of the Persian Gulf. There, monarchies once thought quaint relics of Arab history—including Qatar, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates—have taken on new life. The accumulation of massive oil wealth in the hands of kings and emirs amid soaring demand and prices over the past few decades has given birth to a far more diverse and multipolar Arab world. It has made possible innovations in domestic and foreign policy and supplied vast sums for the building of glittering, hypermodern “global cities” that lure Western and Asian money, business, and tourists away from Cairo.

As the Mubarak era nears its end, Egyptians are not alone in wondering whether a new and more dynamic leader will restore the nation to its central role and take the lead in giving the Arabs a stronger and more united voice in global affairs. Whether any Egyptian leader, or for that matter any Arab leader, can rise to lead this fragmented world will be a central issue in the years ahead. Another is whether Arab unity is any longer a desirable goal.

Arabs have long shared an unusually strong sense of common identity and destiny. The Arab states, unlike those of Western Europe, Africa, Asia, or Latin America, are bound together by a common language and shared religion. They have a border-transcending culture rooted in 1,400 years of Islam, with its memory of the powerful caliphates based in Damascus and Baghdad. With the exception of Saudi Arabia, which escaped the European yoke, they also share a history of fervent anticolonial struggle against France and Britain that began with the crumbling of the Ottoman Empire during World War I. The Ottomans had ruled the Arabs for nearly 500 years, deftly dividing them while governing with a relatively light hand. The Arab Revolt (1916–18) against the Ottoman Turks, led by the emir of Mecca, Sharif Hussein ibn Ali, and abetted by Britain’s legendary Lawrence of Arabia, ignited the dream of a reunified Arab nation…

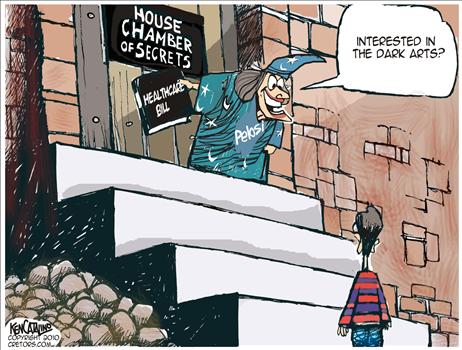

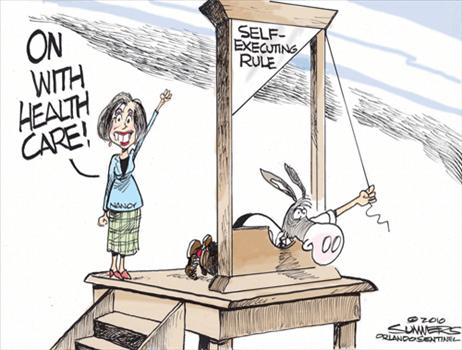

The Dark Arts

March 18, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

The Diagnosis

March 18, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

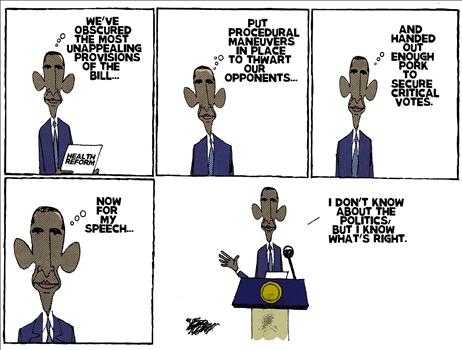

What Do I know?

March 17, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

Anne Frank: The Untold Story At Bergen Belsen

March 17, 2010

Frail, bone-cold and surrounded by death, Jewish teenager Anne Frank did her best to distract younger children from the horrors of a Nazi concentration camp by telling them fairy tales, a Holocaust survivor says.

The account by Berthe Meijer, now 71, of being a 6-year-old inmate of Bergen Belsen offers a rare glimpse of Anne in the final weeks of her life in the German camp, struggling to keep up her own spirits even as she tried to lift the morale of the smaller children.

That Anne had a gift for storytelling was evident from the diary she kept during two years in hiding with her family in Amsterdam. The scattered pages were collected and published after the war in what became the most widely read book to emerge from the Holocaust.

But Meijer’s memoir, being published in Dutch later this month, is the first to mention Anne’s talent for spinning tales even in the despair of the camp.

The memoir deals with Meijer’s acquaintance with Anne Frank in only a few pages, but she said she titled it “Life After Anne Frank” because it continues the tale of Holocaust victims where the famous diary leaves off.

“The dividing line is where the diary of Anne Frank ends. Because then you fall into a big black hole,” Meijer told The Associated Press at her Amsterdam home.

Anne’s final diary entry was on Aug. 1, 1944, three days before she and her family were arrested. She and her older sister Margot died in March 1945 in a typhus epidemic that swept through Bergen Belsen, just two weeks before the camp was liberated. Anne was 15.

The stories Anne told were “fairy tales in which nasty things happened, and that was of course very much related to the war,” Meijer said.

“But as a kid you get lifted out of the everyday nastiness. That’s something I remember. You’re listening to someone telling something that has nothing to do with what’s happening around you — so it’s a bit of escape…”

Her Majesty Has Spoken

March 17, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

Offerings

March 17, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

The overpopulation myth: Growing human numbers will not destroy the planet. Over-consumption will

March 17, 2010

Many of today’s most-respected thinkers, from Stephen Hawking to David Attenborough, argue that our efforts to fight climate change and other environmental perils will all fail unless we “do something” about population growth. In the Universe in a Nutshell, Hawking declares that, “in the last 200 years, population growth has become exponential… The world population doubles every forty years.”

But this is nonsense. For a start, there is no exponential growth. In fact, population growth is slowing. For more than three decades now, the average number of babies being born to women in most of the world has been in decline. Globally, women today have half as many babies as their mothers did, mostly out of choice. They are doing it for their own good, the good of their families, and, if it helps the planet too, then so much the better.

Here are the numbers. Forty years ago, the average woman had between five and six kids. Now she has 2.6. This is getting close to the replacement level which, allowing for girls who don’t make it to adulthood, is around 2.3. As I show in my new book, Peoplequake, half the world already has a fertility rate below the long-term replacement level. That includes all of Europe, much of the Caribbean and the far east from Japan to Vietnam and Thailand, Australia, Canada, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Algeria, Kazakhstan, and Tunisia.

It also includes China, where the state decides how many children couples can have. This is brutal and repulsive. But the odd thing is that it may not make much difference any more: Chinese communities around the world have gone the same way without any compulsion—Taiwan, Singapore, and even Hong Kong. When Britain handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997, it had the lowest fertility rate in the world: below one child per woman.

So why is this happening? Demographers used to say that women only started having fewer children when they got educated and the economy got rich, as in Europe. But tell that to the women of Bangladesh, one of the world’s poorest nations, where girls are among the least educated in the world, and mostly marry in their mid-teens. They have just three children now, less than half the number their mothers had. India is even lower, at 2.8. Tell that also to the women of Brazil. In this hotbed of Catholicism, women have two children on average—and this is falling. Nothing the priests say can stop it.

Women are doing this because, for the first time in history, they can. Better healthcare and sanitation mean that most babies now live to grow up. It is no longer necessary to have five or six children to ensure the next generation—so they don’t.

There are holdouts, of course. In parts of rural Africa, women still have five or more children. But even here they are being rational. Women mostly run the farms, and they need the kids to mind the animals and work in the fields.

Then there is the middle east, where traditional patriarchy still rules. In remote villages in Yemen, girls as young as 11 are forced into marriage. They still have six babies on average. But even the middle east is changing. Take Iran. In the past 20 years, Iranian women have gone from having eight children to less than two—1.7 in fact—whatever the mullahs say.

The big story here is that rich or poor, socialist or capitalist, Muslim or Catholic, secular or devout, with or without tough government birth control policies in place, most countries tell the same tale of a reproductive revolution.

That doesn’t mean population growth has ceased. The world’s population is still rising by 70m a year. This is because there is a time lag: the huge numbers of young women born during the earlier baby boom may only have had two children each. That is still a lot of children. But within a generation, the world’s population will almost certainly be stable, and is very likely to be falling by mid-century. In the US they are calling my new book “The Coming Population Crash.”

Is this good news for the environment and for the planet’s resources? Clearly, other things being equal, fewer people will do less damage to the planet. But it won’t on its own do a lot to solve the world’s environmental problems, because the second myth about population growth is that it is the driving force behind our wrecking of the planet.

In fact, rising consumption today far outstrips the rising headcount as a threat to the planet. And most of the extra consumption has been in rich countries that have long since given up adding substantial numbers to their population, while most of the remaining population growth is in countries with a very small impact on the planet. By almost any measure you choose, a small proportion of the world’s people take the majority of the world’s resources and produce the majority of its pollution…

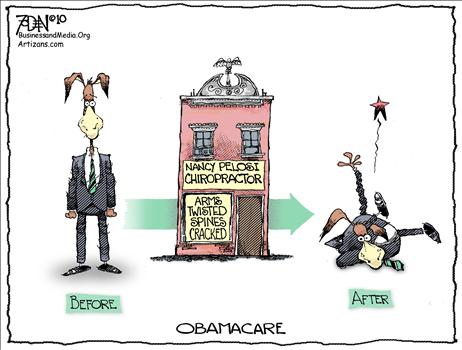

Before And After

March 17, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

Let Them Eat Cake

March 17, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

IT COULD all come down to abortion. Health-care reform hangs in the balance. Nancy Pelosi, the speaker of the House of Representatives, is desperately trying to round up the last few votes. If the House passes a bill the Senate passed in December, it can then be tweaked through the “reconciliation” process and sent to President Barack Obama for signature. But every single House Republican is likely to vote no, so Ms Pelosi needs 216 Democratic votes (out of 253) for a majority. This is proving surprisingly hard. Among the holdouts are a dozen or so pro-life Democrats, several of them Midwestern Catholics, who object to the abortion provisions in the Senate bill.

Thanks to the Supreme Court, abortion has been legally protected since 1973 and neither Congress nor any state has the power to ban it. But a law called the Hyde amendment bars federal funding for abortion, except in cases of rape or incest, or to save the life of the mother. The question now is whether Obamacare will use taxpayers’ money to subsidise abortion more widely. Mr Obama insists that it will not. Under his plan, many individuals and small businesses will buy subsidised health insurance through state-sponsored exchanges. Under the Senate bill, they would only be able to obtain abortion coverage through these exchanges if they paid for it with a separate, unsubsidised, cheque. Thus, federal dollars would be kept out of abortion clinics, say the bill’s supporters. But many pro-lifers are not convinced. So the version of the health bill that was passed by the House would have required those who wanted abortion coverage to buy a completely separate insurance policy. The Democrat who wrote the House abortion provision, Bart Stupak, says he won’t back the Senate bill. Several other pro-life Democrats may also balk.

As a candidate, Barack Obama spoke of soothing the rage that abortion arouses. He promised to seek common ground between the two sides, for example by trying to reduce the number of unplanned pregnancies. But there is only so much common ground between those who think abortion is a fundamental right and those who deem it murder. And since Mr Obama came to power, attitudes have grown less permissive. While a plurality (47%) of Americans still believe that it should be legal in most cases, nearly as many (44%) believe that it should not. Such views are heavily influenced by religion: 71% of white evangelicals but only 25% of religiously unaffiliated Americans would ban it.

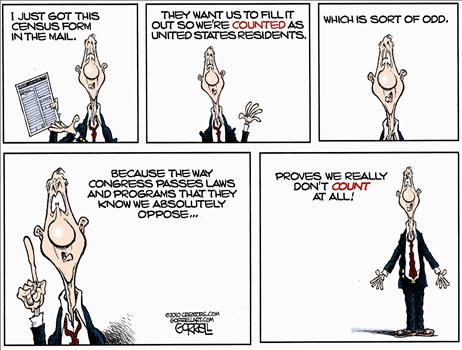

The Census

March 16, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

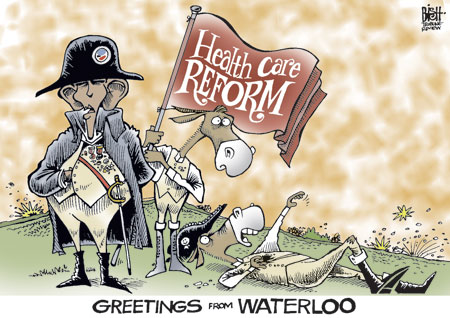

Greetings From Waterloo

March 16, 2010

The Kiss

March 16, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

Sic Semper Tyrannis

March 16, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.

The Plague of the Plagiarists

March 16, 2010

Last month, in what is becoming a perennial scandal in journalism, two writers admitted to plagiarizing in their work. Zachery Kouwe, a young business reporter at the New York Times, resigned after he was found to have lifted passages from the Wall Street Journal on the Times’ DealBook blog. “I write essentially 7,000 words every week for the blog and for the paper,” he told the New York Observer by way of explanation. “I was pushing myself to do as much as I possibly can. I was careless.” Journalist Gerald Posner of the Daily Beast also blamed the accelerated pace of online publishing when he was caught using multiple passages of others’ work without attribution. “The core of my problem was in shifting from that of a book writer-with two years or more on a project-to what I describe as ‘the warp speed of the net,’” he wrote on his blog. He vowed, “I shall not be doing journalism on the internet until I am satisfied that I can do so without violating my own standards and the basic rules of journalism.”

Recent years have also witnessed an increase in what might be called plagiarism-by-design: authors who liberally lift passages from others’ work without attribution but justify their use of it by calling the finished product a “mashup” or “pastiche” of multiple forms. Seventeen-year-old German writer Helene Hegemann, whose novel recently appeared on best-seller lists in Germany, was uncontrite when observers pointed out that she had lifted large passages of her book from a less-well-known novel. Her generation doesn’t see this as thievery, she said, but as a new form of expression that samples and mixes from a multitude of sources to create something new. “There’s no such thing as originality anyway, just authenticity,” Hegemann said in a statement. Similarly, in David Shields’ recent book Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, he calls for a revolution in literature that would allow writers freely to plagiarize from others so as to avoid being “constrained within a form.” “The novel is dead,” Shields declares. “Long live the antinovel, built from scraps.”

In all of these cases the medium that allows for liberal sampling and stealing is technology, particularly the Internet. Kouwe and Posner both blamed it for their plagiarism, while Hegemann and Shields praise it for its wealth of artistic raw material. In fact, what each of these cases suggests is a broader shift in our understanding of personal responsibility and an abandonment of patience in the digital age. The speed and power of the Internet is now invoked to justify behavior that a generation ago would have been considered unethical, but today we are urged to embrace it as a revolution in technique rather than a failure of character…

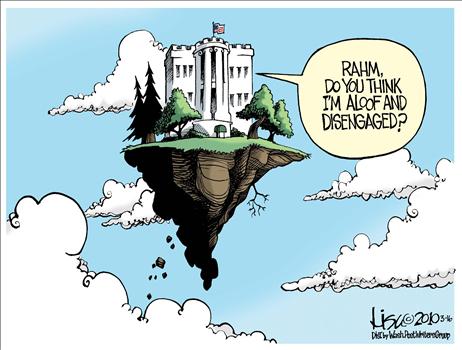

Obama’s Latest Health Care Proposal

March 16, 2010

Good Question

March 16, 2010

This image has been posted with express written permission.

This cartoon was originally published at Town Hall.