Winklevoss Twins Find Great Tool For Separating Suckers, Money

If you have never heard the expression, "a fool and his money are soon parted," then boy do the Winklevoss twins have a golden investment opportunity for you.

The wealthy Winklevii, who famously battled Mark Zuckerberg over their contributions to the creation of Facebook, filed paperwork on Monday for an initial public offering of a new exchange-traded fund tracking the price of bitcoins, the unregulated digital currency. The filing says Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss, presumably out of the goodness of their hearts -- and for a small fee, of course -- will use the ETF to make investing in bitcoins easy and fun for the masses.

And it should make for a fantastic investment, if you don't really care about ever seeing your money again.

"It's an IQ test," wrote an anonymous blogger on the investment blog Macro Man. "Bitcoin is anonymous, untaxed (for now) and quite liquid in and of its own right despite all the complexities of a cryptocurrency. A bitcoin ETF is taxed, has fees, may or may not be liquid at all. So, this is really a test: do you want to facilitate the exit of the Winkelvii from an investment at inflated levels which they will soon be taxed upon or do you want to sit this hand out?"

Back in April, the Winklevii revealed that they owned about $10 million worth of bitcoins, or about 1 percent of all the bitcoin wealth in existence.

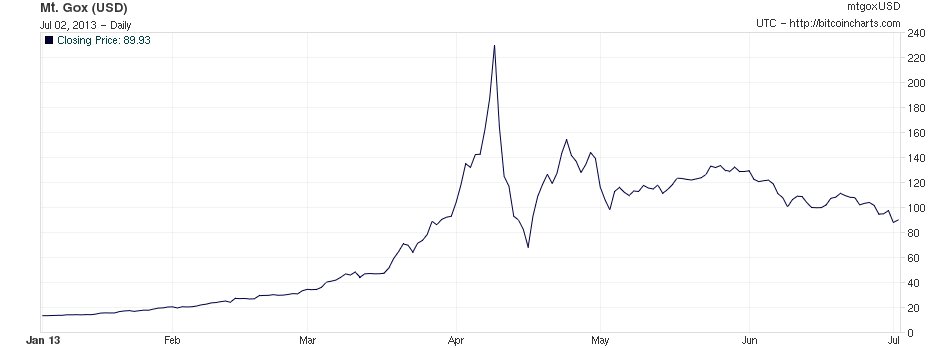

At the time, bitcoins were in the middle of a sickening crash, tumbling from an all-time peak of $266 per bitcoin to $105 in the course of one trading day. The price has stabilized in recent weeks, but has continued on its downward path, recently fetching about $90. (Story continues below chart, courtesy of BitcoinCharts.com.)

This wild price ride is just one of the many, many risks involved in buying an ETF tracking bitcoins. In fact, the section of the IPO paperwork discussing "risk factors" takes up 18 pages -- longer than the filing's 12-page description of what the heck bitcoins even are.

The unusual risks include the possibility that the ETF's bitcoins, which are just digits stored in a computer after all, could accidentally or on purpose be erased from existence forever. A hacker could possibly figure out how to defeat the ETF's security system. A hacker or evil robot could grab control of more than half the processing power on the Bitcoin Network, the global system for producing and distributing bitcoins, which might adversely impact your investment just a touch.

Various governments could also decide to more closely regulate or outlaw the use of bitcoins, which are attractive to money launderers who like the currency's anonymity. The top bitcoin exchange, Tokyo-based Mt. Gox, has, in separate episodes in recent months, temporarily shut down trading and blocked U.S. users from withdrawing their money. A Winklevoss IPO might help legitimize the currency, notes The New York Times, but it will not affect the currency's Wild-West flavor very much. (If this isn't enough, Quartz's Simone Foxman, Bloomberg View's Evan Soltas and Wonkblog's Timothy Lee have each taken a stab at listing the ETF's many risks.)

Of course, many of these are the same risks that anyone takes when buying bitcoins. And the process of buying bitcoins is a bit tedious and complicated, as New York magazine's Kevin Roose found out recently.

But if for some reason you feel you just have to get in on the bitcoin action, you must decide whether your intolerance for the tedium of buying bitcoins is worth the amount of money you will pay the Winklevii for handling that transaction for you.

Meanwhile, any ETF brings with it the risk that its value will not match the underlying value of the assets it holds, as many ETF investors have recently discovered to their horror.

And buying the ETF means you'll be taking on all the risks of bitcoin without some of the purported benefits of bitcoin, such as keeping your cash away from Uncle Sam and his black helicopters or whatever. In fact, you'll be paying taxes on any money you make in that ETF -- assuming you get very lucky and don't lose it all.

Mark Gongloff | July 2, 2013 12:34 PM ET