Biden visit exposed Israeli settler truths

This article was first published at the Guardian Online.

There was a moment of rare clarity this week for America's efforts to advance Israeli-Palestinian peace. The US vice-president Joe Biden was on a visit, ostensibly a charm offensive to an Israel that has been heretofore neglected by the Obama administration's most senior echelons, and an opportunity to discuss broad regional issues, notably Iran. By coincidence, Biden's trip coincided with special Middle East envoy George Mitchell's launching of indirect, or proximity, talks, between the Israelis and Palestinians. Perhaps less coincidental, Biden's presence was greeted by announcements of dramatic new plans for Israeli settlement expansion in East Jerusalem. A crisis in the relaunched Israeli-Palestinian peace talks had apparently arrived a little earlier than expected – day zero to be precise. Not that those resumed negotiations were being greeted by much more than scepticism anyway. For most observers and even participants, the customary and polite suspension of disbelief that normally accompanies a new round of peace talks was barely on display.

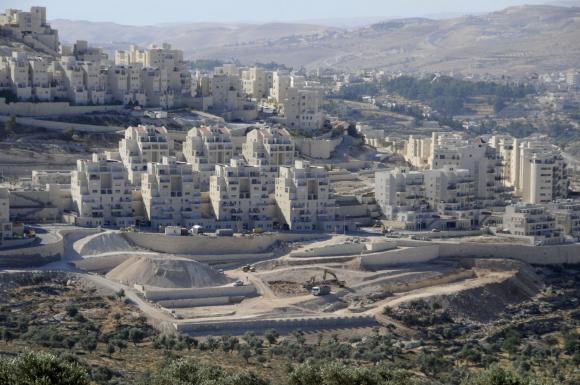

Both sides seemed ready to settle down to a predictable and protracted game of placing blame for failure at the other's door. Then, on the day of Biden's arrival, Israel announced plans to market 112 new housing units in the West Bank and bettered that 24 hours later (shortly after the Biden-Netanyahu confab) when a district committee gave planning authorisation to 1,600 new units in East Jerusalem.

What provided this episode with refreshing clarity was the way in which it exposed the deeper dynamics that are driving contemporary Israeli realities.

Netanyahu seems to have been genuinely blindsided by this development. Israel's settlement addiction proved stronger even than the prime minister's desire to spend a few days going settlement cold turkey. Israel's leadership scrambled to summon their best explanations and apologies – the decision was insensitive, ill-timed, a local initiative, and a mere technical planning detail. If only the decision had been taken two days or two weeks earlier or later everything would have been OK. And so in one fell swoop the naked Israeli settler reality was exposed in all of its absurdity.

For the rest of the world, East Jerusalem, just like the West Bank, is occupied territory; all settlements over the Green Line are illegal (even if not everyone always uses that word). For Israel's leaders, the timing may have been unfortunate, but the impulse to settle Palestinian land is fundamentally sound. Palestinian land is claimed as state land or confiscated, plans are authorised, tenders are issued, construction begins, and settlers move in. After more than 40 years, and endless seemingly trivial and mundane bureaucratic decisions, over 500,000 Israelis now reside beyond the Green Line (for a detailed analysis of this process, read East Jerusalem settlement experts Daniel Seidemann and Lara Friedman here). The settlers and their sympathisers are entrenched in every relevant nook and cranny of Israel's bureaucracy and security establishment. The momentum that they can now generate (especially but not only when their sympathisers hold senior government office), is stronger than Israel's demographic concerns, is stronger than fear of Israel acquiring an international pariah status, and as was proven this week, is stronger than the needs of the US-Israel relationship. America's vice-president has just seen this dynamic first hand and up close.

Mainstream Israeli commentators were apparently shocked to discover the power of the settler momentum. Pundits such as Ari Shavit, known for their staunch nationalism and vilification of human rights groups working in the territories, had a rude awakening. In Ha'aretz he described "the settlements in the West Bank that serve the centrifuges in Natanz [Iran]. If sane Israel does not wake up, it will be defeated by the metastasising of the occupation and the lack of the central government's ability to stop it."

And that, in a nutshell, is why Benjamin Netanyahu may be our last, best chance for a two-state peace deal.

The extremism and excesses of his government may finally open enough eyes and lead to enough local and international action to roll back this settler behemoth. More moderate Israeli governments, even those perhaps sincerely committed to a variation on the de-occupation, two-state solution theme, have definitively failed to halt the settlements march. When Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert were negotiating on paper potential Israeli withdrawals, the settlements and the occupation were being expanded and entrenched on the ground. Even when Ariel Sharon was removing 7,500 settlers from Gaza, he was adding a greater number to the West Bank and East Jerusalem. But under Netanyahu, what you see is what you get.

And perhaps this clarity and this exaggeration is exactly what is needed. Everything else, all the relevant actors, were stuck in an ugly paralysis. The Palestinians remain divided and devoid of strategy. For 20 years the Fatah-led PLO had been waiting for the US to deliver Israel for an equitable two-state outcome. The only alternative to negotiations to gain any traction had been indiscriminate and unjustifiable violence. The Arab states had produced a breakthrough peace initiative in 2002 but it never translated into a programme for public diplomacy or even pressure to be brought to bear on Israel, America, or the Quartet. The US and EU continue to place their faith in confidence-building measures and unmediated negotiations between the parties, hoping against hope that a formula which had failed for over a decade would produce a breakthrough and that rational argument might prevail.

Not surprisingly, none of this was going anywhere. It has taken a Netanyahu-led extreme right, religious government in Israel (the defunct Labor party of Ehud Barak can be justly ignored as window dressing) to send a signal strong enough to perhaps pierce this paralysis. Israelis and Palestinians, it is clear, are in an adversarial relationship, talk of partnership is premature, talk of confidence-building is naive. Transparently run Palestinian institutions and well-groomed Palestinian security forces will not remove the settler-occupation complex. And neither will gentle persuasion. The naked extremity of the Netanyahu government is producing new international initiatives and new coalitions.

In Jewish diaspora communities, there is a determination to reclaim a more moderate and progressive vision of what it means to be pro-Israel and to apply Jewish ethics and Jewish values, that helped guide civil rights struggles in the past, to contemporary Israeli reality. Such efforts are gaining ground – notably the emergence of J Street in America. Inside Israel, a new progressive discourse, still lacking real parliamentary representation, is struggling to make its voice heard in civil society—notably in weekly demonstrations at Sheikh Jarrah. On the Palestinian side, alternative strategies to the negotiation dependency or violence that dominated the past are gaining ground – especially in non-violent resistance to land confiscations and the separation barrier. Prime Minister Fayyad's plan for statehood by mid-2011 could become a significant hook if it develops some teeth.

European actors have been toying with initiatives of their own in adapting to this new reality. All 27 member states achieved a remarkable consensus in endorsing the most powerful and comprehensive statement of EU policy last December. Lady Ashton, at least declaratively, has gotten off to an impressive start and will be visiting the region next week, and crucially Gaza will be on her itinerary. Britain is taking the lead in imposing labelling on settlement products, and the French and Spanish governments are exploring options for advancing Palestinian statehood even in the face of peace process stalemate.

None of this would likely have happened if the government in Israel was nice-sounding and well-intentioned, but ultimately hapless in the face of the settler-occupation complex. Nothing is also likely to really come to fruition without the US assuming leadership. These new developments may serve to create an environment in which there is more political space for the US to operate in.

US administrations have helped generate moments of decision for Israel in the past and not only in the Egyptian peace deal and full evacuation of the Sinai brokered by President Carter. President Bush confronted Yitzhak Shamir with the withholding of loan guarantee monies, leading to the election of Yitzhak Rabin in 1992 in a campaign in which settlements and opposition to them featured prominently. Benjamin Netanyahu's first term in office ended abruptly when President Clinton challenged him to sign, and then implement, the Wye River Memorandum of 1998, something his coalition could not sustain and which led to the election of Ehud Barak, ushering in at the time a moment of great hope.

The realities today are no longer the same. The Israeli inability to confront its own settler-occupation demon is more deeply entrenched. Israel will have to be presented with clear choices, clear answers to its legitimate security and other concerns, and clear consequences for nay-saying. A successful effort will also have to be more comprehensive and more regional in its scope, almost certainly involving Syria and bringing Hamas into the equation. No one should expect this to be easy. But if one person can generate American will to lead such an effort and an international alliance to see it through, then surely that person is the Israeli leader who we saw on display in all his glorious stubbornness this week.

linkage between reaching peace with the Palestinians and addressing the Iran issue:

linkage between reaching peace with the Palestinians and addressing the Iran issue:

I am currently engaged in an

I am currently engaged in an