REUTERS

There was a time, not so long ago, when cars supposedly personified the American character. Our aggression, our style, our rugged independence. In the last 30 years, the automobile has faded slightly in the American imagination, but today the car industry does, in fact, explain the American economy.

It is a surprisingly durable, fantastically productive juggernaut, whose success relies on the old, the rich, and foreign trade -- and less on American workers.

***

To begin this story, let's appreciate the big picture. The car economy, a small but mighty sliver of American industry, has been on a roll. Since 2009, car production has nearly doubled, accounting for between 15 and 20 percent of our whole recovery.

Ford and GM said this past August was the best month for car sales in seven years. JD Power is saying it might be the best month on record. But man cannot live on cars alone, and neither can countries. "We're not big enough to tow the whole boat," Sean McAlinden, chief economist at the Center for Automotive Research, told me. "It's lonely all out there by yourself."

For decades, housing has been the engine the moves recoveries. When people would clean up their debt, they'd swing a house. And, at least since 1950, a house meant a garage, and a garage meant a new car. As Jordan Weissmann has written , cars and houses accounted for more than half of the recovery in the 1970s, a third of the "Reagan Recovery" in the early 1980s, a sixth of the recoveries in the early 1990s and 2000s.

But this time, cars are leading houses, thanks to a surprising source: older Americans. "[Demand] is coming from an increased buying rate of people over 55," McAlinden said, "which is scary because we don't have a lot of repeat sales left in us."

Young people are essentially locked out of the car market, just as they have been locked out of the housing market -- and the labor market. Average vehicle prices are as high as ever, but wages are low, and unemployment for young people has typically been twice as high as for the overall population. There is also evidence that cars have fallen from their cultural perch, squeezed by urbanization among young people and the growth of a new, expensive, social, mobile technology -- the smartphone.

Young vs. old might not be the most important binary for car companies. That would be rich vs. poor. The U.S. is beginning to look like the aristocratic auto market we're used to seeing in Europe, McAlinden said, where the top 25 percent buys most of the new cars and the bottom 75 percent only buys old and used. "Seventy-five percent of households here are relying on used cars, thinking 'I hope that rich guy is done,'" he said.

Plutocracy in the car market isn't unique, but rather illustrative. There is “no such animal as the U.S. consumer,” three Citigroup analysts concluded in the heart of the real estate boom in 2005. Instead, we have the rich and the rest. As Don Peck wrote in his summer 2011 cover story for The Atlantic, for many industries, "the rest" just don't matter.

All the action in the American economy was at the top: the richest 1 percent of households earned as much each year as the bottom 60 percent put together; they possessed as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent; and with each passing year, a greater share of the nation’s treasure was flowing through their hands and into their pockets. It was this segment of the population, almost exclusively, that held the key to future growth and future returns.

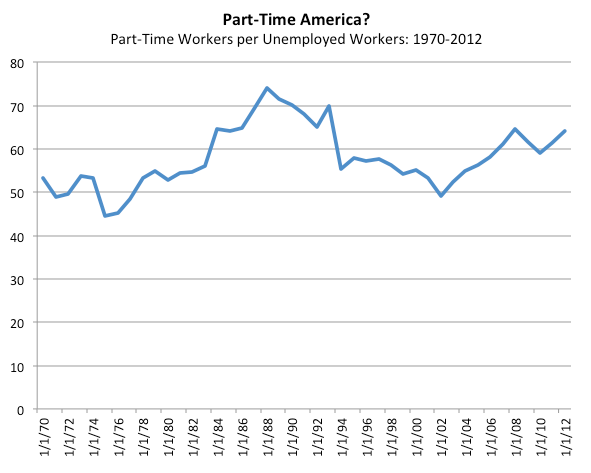

The last two years have done nothing to make those Citigroup economists look anything less than prophetic. Middle-income jobs (like, say, auto-parts workers) made up 60 percent of jobs lost in the recession, but lower-wage occupations have accounted for about 60 percent of jobs gained the recovery. The auto recovery, like the U.S. recovery, is built on a fragile assumption: The rich can be rich enough for the rest of us.

So Much Work, So Where Are the Jobs?

The amazing car comeback has not translated into equally amazing jobs. Auto manufacturing employment is up since 2009, but whereas the motor industry has accounted for 15 to 20 percent of economic growth, it's accounted for just 2 to 3 percent of job growth. "We're at record productivity levels," McAlinden said. But productivity across the industry hasn't trickled down as better pay or equally rising employment. Instead, car companies are making more with less. According to CAR figures shared with The Atlantic, total motor vehicle output has grown 75 percent faster than total industry employment.

Why? First, the auto industry is seeing record levels of overtime. Second, car companies are relying on logistics and trucking companies -- not typically counted in auto manufacturing categories -- to work in and around the factories today to assist with assembly and sequencing of parts. These workers, even if unionized, tend to be paid less than members of the auto union. Third, car companies are importing more finished parts from Mexico -- hatchbacks, body panels, electronics -- which means cheaper Mexican workers have replaced Americans.

Data shared by Yen Chen, a senior economist at CAR, shows auto imports from Mexico on an absolute tear since 2009, far outstripping China, Canada, and Japan.

"We suspect that the record levels of parts imports is a big reason why employment is stuck in the rut," McAlinden said. The parts sector in Mexico employs 540,000 people, compared to about 480,000 in the U.S. Remarkably, Mexico's industry is already "bigger" than the United States. As we've seen with other global industries, American employment has been restrained by large companies moving more labor along their supply chain to cheaper countries. American companies simply don't need that many more Americans.

***

The modern auto recovery is, over all, a sensational story. We need growth, and we're getting more of it from cars than perhaps another other industry.

But unpacking this story reveals a more frightening picture of American industry and productivity. In the mid-20th century, a strange and wonderful blip of good fortune for the American middle class, unions concentrated in the manufacturing sector helped millions of American families achieve healthy and rising wages, thanks to collective bargaining and a burgeoning industry that wasn't yet automated or globalized. But that story is over. It has been replaced by a new American story where one of the country's most iconic industries scarcely needs more American workers to do all the work it needs.