Archive for

December, 2013

by Julian Ku

I’ve been working hard this break teaching in Hofstra’s winter program in Curacao. But I couldn’t resist stepping away from the beach and posting on the India-US flap over the arrest of an Indian diplomat in New York. Dapo Akande at EJIL Talk! has two great posts on the consular and diplomatic immunity legal issues. I have nothing to add, but wanted to focus on how the ICJ could actually play a role in resolving (or not resolving) this dispute.

As those following the incident may know, Devyani Khobragade, India’s deputy consul-general in New York, was arrested and charged with lying on her visa applications about the salary she was paying the maid she had brought from India. As a consular official, Khobragade could only assert functional rather than absolute immunity. Most of the outrage in India is about her treatment after arrest (which does seem excessive to me as well), but the legal issues mostly have to do with her immunity from arrest.

As Dapo points out, India may now be asserting that at the time of the arrest, Khobragade had already been transferred to India’s U.N. Mission. This might entitle her to the broader protections of U.N. diplomatic immunity as oppose to mere consular immunity. According to Dapo, Section 11(a) of the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations may grant her absolute immunity from arrest (but not from prosecution). India may also argue shifting her to the UN mission now gives her immunity from arrest going forward, even if she wasn’t a UN diplomat at the time of her arrest. Thus, on this theory, Khobragade could at least leave the U.S., or even wander New York free from the possibility of arrest or detention, even though the criminal prosecution would go forward.

Much of this would turn on whether Khobragade would need U.S. consent to acquire diplomatic status within the U.N. Again, I am far from expert on this but it seems a murky legal issue at best with plausible arguments for both sides based on the U.S./UN Headquarters Agreement and the Convention on Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations.

Sounds like a case for international dispute settlement! It turns out there are mandatory dispute settlement procedures under both agreements. The U.S./UN Headquarters Agreement allows the U.N. to take the U.S. to compulsory arbitration pursuant to Section 21. This would require the U.N. to side with India’s view on Khobrogade’s diplomatic status, but this is hardly impossible or even improbable that they would support a broad view of UN diplomatic rights and immunities.

Interestingly, India could also take the U.S. to the ICJ under Article VIII, Section 30 of the Convention on Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations.

SECTION 30. All differences arising out of the interpretation or application of the present convention shall be referred to the International Court of Justice, unless in any case it is agreed by the parties to have recourse to another mode of settlement.

Somewhat surprisingly, both India and the U.S. have signed on to the Convention without trying to limit the effect of this provision through a reservation (as China and others have done). Such a reservation may be of little effect anyway, but at least it would be an argument against ICJ jurisdiction. So I think that India could bring an ICJ case seeking a provisional measure guaranteeing Khobragade’s immunity from arrest under Article 11(a).

It is possible the U.S. would simply ignore any ICJ order, but this is not quite the same as the Medellin cases. First of all, it is the federal government rather than the state governments involved here, and the President probably has authority to order federal agents NOT to arrest Khobragade. Furthermore, the U.S. interest here is far weaker than in the Medellin case, which involved individuals who had been convicted of murder. In this case, the U.S. may be upset over allowing an alleged visa-fraudster to walk, but it is of a completely different magnitude than giving a new hearing to a convicted murderer.

In my view, it would be a perfectly legitimate exercise of presidential power to order executive branch officials to refrain from further action in this case. An ICJ provisional measures might provide a clearer justification for the President’s decision, although I think he probably has the authority right now to stop all of this. But the ICJ might provide a face-saving way for both sides to resolve this deeply fractious incident.

In any event, it will be interesting to see if India chooses the ICJ route. Or if the US even invites an ICJ resolution of this conflict. Indeed, if India goes to far in its retaliations against US diplomats, the U.S. might take India to the ICJ under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations!

The current ICJ even has one Indian judge, and one U.S. judge. One problem for India is that its legal position is hardly flawless, and it could very well fail in the ICJ. But if India thinks it has strong legal arguments (and they do look fairly strong to me), it seems like a textbook case for the ICJ. Indeed, since neither side shows any sign of backing down, I think the ICJ might actually be useful here.

December 30th, 2013 - 10:25 PM EDT |

Trackbacks(1) | 5 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/30/india-us-diplomatic-incident-resolved-icj/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

Train wreck, fiasco, disaster, dumpster fire, bad joke, kangaroo court, show trial — take your pick, the description applies. Eviatar’s post at Just Security a while back is a must-read; here is but one particularly disturbing snippet:

Recent pre-trial hearings have revealed, for example, that the Guantanamo courtroom was equipped with microphones able to eavesdrop on privileged attorney-client communications; that the CIA was secretly monitoring the hearings and, unbeknownst to the judge, had the ability to censor the audio feed heard by observers; and that the meeting rooms where defense lawyers met their clients had been secretly wired with video and audio monitors, hidden in devices made to look like smoke detectors. In addition, all legal mail is screened by government security personnel, and documents previously deemed acceptable were later confiscated from the defendants’ prison cells without explanation; those documents included a detainee’s own hand-written notes or a photograph of the grand mosque in Mecca.

Seventy years ago, the United States bent over backwards to provide high-ranking Nazis with fair trials. These days, a fair trial for someone as unimportant as bin Laden’s driver is nothing but a dream. How far the mighty have fallen.

December 30th, 2013 - 6:59 AM EDT |

4 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/30/jennifer-daskal-train-wreck-military-commission-system/ |

by An Hertogen

Your weekly selection of international law and international relations headlines from around the world:

Africa

Americas

- Edward Snowden has declared “mission accomplished” and also issued an alternative Christmas message for the UK’s Channel 4.

- Legal or not? A federal District Court judge in New York has ruled that the NSA data collection is legal, a week after a District Court judge in DC ruled it illegal.

Asia

Europe

Middle East

December 30th, 2013 - 2:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekly News Wrap: Monday, December 30, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/30/weekly-news-wrap-monday-december-30-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

John Sexton, the controversial President of NYU, has spoken out against the American Studies Association’s much-debated resolution in favour of boycotting Israeli universities. Here is his statement, issued jointly with NYU’s provost:

We write on behalf of New York University to express our disappointment, disagreement, and opposition to the boycott advocated by your organization of Israeli academics and academic institutions.

This boycott is at heart a disavowal of the free exchange of ideas and the free association of scholars that undergird academic freedom; as such, it is antithetical to the values and tenets of institutions of advanced learning.

I have no desire to wade into the debate over academic BDS, other than to say I’m generally wary of academic boycotts, but find it distressing that those who criticize the ASA for undermining academic freedom somehow never get around to criticizing Israel for its ongoing repression of Palestinian academics and students.

That said, NYU is the last university that should be issuing flowery defences of academic freedom. As Anna Louise Sussman points out in The Nation, President Sexton has not only refused to criticize the repression of academics in the UAE, where NYU has a campus, he has made statements that actually justify that repression:

Since April 8 the Emirati government has arrested five prominent Emiratis—activists, bloggers and an academic—for signing a petition calling for reform, and thrown them in jail, where they remain to this day. They are being held without charges, although they are in contact with their families and lawyers.

[snip]

Dr. Christopher Davidson, a reader in Middle East politics at Durham University who specializes in the politico-economic development in the Gulf, believes that by arresting people like Professor bin Ghaith, a high-profile academic, the government hopes to show that no one—no matter how connected they are—is beyond the government’s reach. Even Professor bin Ghaith’s connections to Paris-Sorbonne couldn’t save him, although Davidson chalks that up to the Sorbonne’s notable lack of response.

[snip]

According to NYU sociology Professor Andrew Ross, who has been an outspoken critic of the university’s involvement in the autocratic city-state, NYU president John Sexton recently told a group of concerned faculty members that he had reason to believe those arrested were a genuine threat to national security, something that Professor Lockman finds “particularly shocking.”

“He suggested that these people were genuinely subversive and deserving of arrest, although human rights organizations, of course, have a different take,” said Lockman. “This kind of toadying to the crown prince and his ilk shows the hollowness of NYU’s role in this place.”

Ross and his colleagues at the New York chapter of the American Association of University Professors sent a letter addressed to Dean Sexton and Vice-Chancellor Al Bloom, warning that “Silence on this serious issue will set a precedent that could also have ominous consequences for the speech protections of NYUAD faculty.”

Apparently, academic freedom is important to NYU only when it’s Israeli academics whose freedom is at stake. The academic freedom — and actual freedom — of academics in states in which NYU has business interests? Not so much.

Hat-Tip: Max Blumenthal.

NOTE: For more about President Sexton’s unwillingness to defend academic freedom in the UAE, see this essay in The Atlantic. The articles notes that, ironically, the UAE discriminates against Israeli students who want to study in the country.

December 27th, 2013 - 7:08 AM EDT |

Trackbacks(3) | 42 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/27/nyus-selective-dedication-academic-freedom/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

At long last, Amnesty has weighed in on the debate between me and Ryan about its methodology for determining whether a state exercises universal jurisdiction over at least one international crime. As I expected, and contrary to Ryan’s claim, Amnesty does not consider it sufficient for a state to have incorporated the Rome Statute into its domestic legislation. On the contrary, it requires the existence of domestic legislation that extends universal jurisdiction over an international crime, whether specifically (“this legislation provides universal jurisdiction over international crime X”) or generically (“this legislation provides universal jurisdiciton over all international crimes defined in ratified treaties”). Here is the key statement from Amnesty’s response:

[T]he above mentioned conclusions are not based on counting “[s]tates as having enacted universal jurisdiction if the state is a party to the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court or, more precisely, if the state has adopted a form of implementing legislation along with ratification of the treaty”. That would be a mistake. For example: Chad, Gabon, Maldivas, Nauru, and Zambia – which are states party to the Rome Statute are enlisted in the report as not providing for universal jurisdiction for any of the crimes defined in the Rome Statute. And Ireland and Liechtenstein – which have ratified the Rome Statute and enacted legislation implementing it into national law — are also both considered as not providing for universal jurisdiction with regard to crimes against humanity and genocide. In sum, Amnesty International considers that the domestic law in these countries has the effect of conferring universal jurisdiction over crimes defined in, for example, the Rome Statute. Therefore Amnesty International are not basing the claim that such countries have universal jurisdiction on the fact of their ratification of the Rome Statute alone but rather on domestic legislation that enacts universal jurisdiction for all crimes in treaties (including for example the Rome Statute) that they have ratified.

Unfortunately, Ryan still insists that Amnesty is overcounting the number of universal jurisdiction states. Here is his response, in relevant part:

In other words, the problem with the coding procedure is that it appears to involve the following two steps:

Step 1: the proposition that the Rome Statute obligates state parties to enact universal jurisdiction for ICC crimes

Step 2: the decision to code a state as having enacted universal jurisdiction if it (a) is a party to the Rome Statute and (b) its domestic law provides for jurisdiction over crimes obligated by international treaty

As I explained in my original post, Step 1 is flawed. The Rome Statute does not include universal jurisdiction, and has no obligation whatsoever for state parties to provide (extraterritorial) jurisdiction for ICC crimes.

I suspect that the reason Amnesty sets forth the two steps as a part of its coding procedure is because it is meaningful – i.e., that it makes a difference in their results. It is difficult to discern, from the Annexes of the study, which particular states might be affected, because the relevant information is not provided.

There are a number of problems with this response. To begin with, there is no “Step 1” in Amnesty’s analysis…

December 26th, 2013 - 7:21 PM EDT |

Comments Off on Another Round in the Amnesty-Goodman-Heller Debate over Universal Jurisdiction http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/26/amnesty-responds-ryan-goodman-re-universal-jurisdiction/ |

by Peter Spiro

Citizenship practice and policy is mostly below the news radar; change is slow; and the field tends not to be reported in any sort of integrated way. So here are the key threads from 2013 and how they might spin out in 2014.

1. Citizenship is not priceless. A growing number of states are selling citizenship. Malta is the latest. EU citizenship can be yours for 1.15mn Euros. Hungary, Spain, and Portugal now offer permanent residency in return for smaller investments in residential property, which can lead to citizenship in short order; and Cyprus tossed consolation passports to foreigners who lost more than three million Euros in the country’s banking collapse. The trend has been somewhat predictably lamented by liberal nationalists (see this forum, for example, on EUI’s excellent citizenship observatory site, with a lead contribution from Ayelet Shachar), but look for other states to cash in on a commodity that has no effective marginal cost. Will 2014 see a passport price war?

2. Even the Germans can live with dual citizenship. Americans will have a hard time understanding how big a flashpoint dual citizenship has been in German politics over the last 15 years. As a condition for remaining a part of Angela Merkel’s coalition after recent elections, Social Democrats secured the elimination of the so-called “option model” that had required German-born dual nationals to renounce one or the other by age 23. Dual Turkish-German citizens living in Germany are the big winners. If Germans can live with dual citizenship, any country can. Expect the dramatic trend towards acceptance of the status to move into its mopping up stage, with remaining holdouts (e.g., Japan) giving up their old-world jealousies.

3. American no more. 2013 saw a continued uptick in the number of individuals renouncing U.S. citizenship, with Tina Turner following in the footsteps of Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin, along with thousands of ordinary Americans living abroad. Taxes supply the clear motivation, as much the burdensome administrative requirements imposed by the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) as the payment obligations themselves. Expat websites are aflame with outraged citizens ready to cut the cord. Expect this story to get closer to the front burner as FATCA enforcement kicks in during 2014. Do external Americans have enough political clout to repulse this IRS juggernaut?

4. Foreigners have privacy rights, too. In the NSA’s massive post-9/11 surveillance apparatus, it was open season on non-citizens outside the United States. With good jurisprudential reason: the Supreme Court (in Verdugo-Urquidez) squarely held that non-resident foreigners have no Fourth Amendment rights against the U.S. government. But that understanding is under pressure from other quarters. There’s the prospect of an international right to privacy. That won’t have much effect on America’s spymasters, at least not in the short run. The President’s NSA review board might be more influential. Its recent report called for substantial limitations on eavesdropping on foreigners (see pages 155-56). It will be interesting to see whether Obama buys in.

5. A human right to citizenship. The Dominican Republic came under withering human rights fire after its Supreme Court declared Dominican-born individuals of undocumented parents (almost all Haitian) not to enjoy Dominican citizenship. The ruling leaves 200,000 effectively stateless. Those crying foul included the major human rights groups, the UN, major powers, the Caribbean Community, and the Dominican diaspora. Expect the DR to reverse course during the coming year or face some material consequences. Other states are also coming under increasing scrutiny for rights-problematic citizenship practices. The Gulf States are getting more bad press for their notoriously ungenerous naturalization laws. Notwithstanding significant goodwill in the wake of the transition to democracy, Burma is not getting a free pass on its continuing refusal to facilitate citizenship for the Rohingyas. Human rights-based citizenship claims are clearly on the upswing, a context in which sovereignty once supplied a trumping defense.

6. Obama’s gives up on The New Citizenship. President Obama centered citizenship as a theme in a number of high profile speeches, including the trifecta of his nomination acceptance speech, his second inaugural address, and the State of the Union. In his words, citizenship “describes the way we’re made. It describes what we believe. It captures the enduring idea that this country only works when we accept certain obligations to one another and to future generations.” Lofty rhetoric, but nobody seemed to notice. Don’t expect any more stabs at this one. Much as he would like it to, this will not go down as the defining label of the Obama Presidency.

7. Ted Cruz may be a Canadian, but he is eligible for the presidency. There’s a delicious irony in the fact that the candidate most attractive to Obama-obsessed birthers himself has a much bigger question-mark relating to presidential eligibility. But even though Ted Cruz was born in Canada (and holds Canadian citizenship as a result), he is almost certainly eligible to run for president as a “natural born” U.S. citizen, holding citizenship at birth through his mother. Cruz says he has applied for termination of his Canadian citizenship. Expect the questions to linger if his candidacy looks viable; it’s just too easy a poke in the Tea Party gullet.

8. The path to legal residency matters more than the path to citizenship. At least among those affected, namely, 11-13 million undocumented aliens in the United States, as evidenced in a Pew Hispanic Center poll and reported by Julia Preston in a NYT story here. This can’t be surprising, since the main drawback of being out of status is locational insecurity. So why the persistence of the popular political tagline, “a path to citizenship”? It plays better for political proponents of regularization by lending their agenda a high-minded civic orientation. It also seems required by American notions of equality: we can’t just give undocumented aliens permanent residence insofar as it would offend baseline equality norms. Could reform advocates cave on this in 2014 if it presents the only path to a deal? Maybe.

9. Recementing ties to long-lost brothers and sisters. Spain followed through on its 2012 promise to extend citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain half a millennium ago. Though meaningful ties persist (including in a still-living language spoken by Sephardi), one might wonder if the Spanish government was looking to capitalize on somewhat tenuous ties to its economic advantage, granting citizenship to nonresidents at the same time residents (Moroccans, for example) face significant obstacles to naturalization. More controversially, Hungary moved ahead with policies to extend citizenship — and the vote — to nationalistic co-ethnics in neighboring Slovakia and Romania supportive of the right-wing government in Budapest. Look for more countries to strategically relax requirements for citizenship by descent as they increasingly see diaspora populations as an economic and/or political resource.

And a couple to watch for 2014: what would be the UK/EU citizenship mechanics of Scottish independence; will increasingly common birth tourism packages revive efforts to scale back birthright citizenship in the US; and how will citizenships of convenience play out in the Sochi Olympics. Happy New Year!

December 26th, 2013 - 7:05 PM EDT |

Trackbacks(1) | 6 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/26/2013-nine-trends-citizenship-practice/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

I have posted a new essay on SSRN entitled — borrowing a phrase from a dissent written by Judge Van den Wyngaert — “A Stick to Hit the Accused with”: The Legal Recharacterization of Facts Under Regulation 55. The essay is forthcoming in a book on the ICC that Carsten Stahn is editing for OUP. Here is the abstract:

Regulation 55 was one of 126 regulations adopted by the judges of the International Criminal Court on 26 May 2004. It permits a Chamber to legally recharacterize the facts contained in the prosecution’s Document Containing the Charges, subject to certain important procedural constraints. This Chapter provides a comprehensive critique of Regulation 55, which has already had a significant impact on at least three cases: Lubanga, Bemba, and Katanga. Section I argues that the judges’ adoption of Regulation 55 was ultra vires, because the Regulation does not involve a ‘routine function’ of the Court and is inconsistent with the Rome Statute’s procedures for amending charges. Section II explains why, contrary to the practice of the Pre-Trial Chamber and Trial Chamber, Regulation 55 cannot be applied either prior to trial or after trial has ended. Finally, Section III demonstrates that the Pre-Trial Chamber and Trial Chamber have consistently applied Regulation 55 in ways that violate both prosecutorial independence and the accused’s right to a fair trial.

It’s difficult to overstate how problematic Regulation 55 is. Katanga is perhaps the best example: the defence built its entire strategy around rebutting the idea that Katanga was responsible for the charged crimes as an indirect co-perpetrator, in keeping with the OTP’s allegations and the Pre-Trial Chamber’s assurance that questions of complicity were thereby moot. Katanga testified on his own behalf at trial, admitting that he had known about and perhaps indirectly contributed to his former subordinates’ crimes, but denying he intended to commit the charged crimes or had control over them (the material elements of indirect co-perpetration). The Trial Chamber then notified the defence six months after trial was over that it intended to also consider Katanga’s responsibility on the basis of common-purpose liability — relying to a significant extent on Katanga’s own testimony. And the Appeals Chamber thought that was just fine.

I could go on — but if you’re interested, you should just read the essay. You can download it here. Comments most welcome, as always.

December 23rd, 2013 - 12:57 PM EDT |

12 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/23/new-essay-legal-recharacterization-facts-icc/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Your weekly selection of international law and international relations headlines from around the world:

Middle East

- British and U.S. spies targeted a senior EU official, German government buildings, and the office of an Israeli prime minister, according to the latest leaked documents from Edward Snowden published on Friday. Israeli officials said they were not surprised by allegations of spying and played down the importance of any information its allies may have gleaned.

- In a rare public apology, the military leader of al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen has said that one of his fighters disobeyed orders and attacked a hospital attached to the defense ministry during a December assault that killed 52 people.

- Israeli police have blamed terrorists for a bomb that exploded on a bus in the Tel Aviv suburb of Bat Yam only moments after passengers left the vehicle.

Asia

Africa

Europe

Americas

December 23rd, 2013 - 5:49 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekly News Wrap: Monday, December 23, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/23/weekly-news-wrap-monday-december-23-2013/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Calls for Papers

- The Stanford Journal of International Law seeks contributions by academics, practitioners, and policymakers for its Symposium titled Governing Intelligence: Transnational Threats & the National Security State, which will take place on May 2, 2014 at Stanford Law School. Governing Intelligence will move beyond the surveillance debate to start an interdisciplinary dialogue about the power and limits of intelligence agencies from a comparative and international perspective. Contributions must address either of the following topics: (a) National Intelligence & Transnational Threats; or, (b) Individual Rights & Intelligence Gathering. The abstract submission deadline is February 1, 2014. Decisions will be released on a rolling basis. The full announcement, along with sub-topics, contact information, and submissions guidelines, can be found here.

- The Journal of International Criminal Justice (JICJ) invites submissions for a Special Issue provisionally titled The Interaction between Refugee/Migration Law and International Criminal/Humanitarian Law. The editors welcome submission of abstracts not exceeding 400 Words on any of the themes described above, or related areas of interest, on or before 28 February 2014, by email, at jicj [at] geneva-academy [dot] ch. The abstract should contain the author’s name, home institution, and the title of the proposed paper. Please also send a current CV. For more information, please click here (.doc).

- The Utrecht Journal of International and European Law is issuing a Call for Papers to be published in its forthcoming general edition on International and European Law. The Board of Editors of Utrecht Journal invites submissions addressing any aspect of International and European law; topics may include, but are not limited to, International and European Human Rights Law, International and European Criminal Law, Family Law, Health and Medical Law, Childrens’ Rights and the Law, Commercial Law, Media Law, Law of Democracy, Intellectual Property Law, Taxation, Comparative Law, Competition Law, Employment Law, Law of the Sea, Environmental Law, Indigenous Peoples, Land and Resources Law, Alternative Dispute Resolution or any other relevant topic. Deadline for Submissions: 30 March 2014. Author guidelines and more information can be found here.

- The Grotius Center of Leiden University in The Hague has announced a call for papers for its upcoming seminar: Peacebuilding and Environmental Damage in Contemporary Jus Post Bellum: Clarifying Norms, Principles and Practices taking place June 11 – 12, 2014. Traditional approaches to environmental protection face particular challenges during and after conflict. Calls for the acceptance of specific ecological obligations and procedures in post-conflict environments encounter resistance and constraint in military operations. Some harms and obligations lend themselves to systemic or abstract regulation. Others require context- and case-specific consideration. Jus post bellum provides a potential framework to take into account these specificities. It allows exploration of otherwise disparate areas of law and practice under a unified framework that focuses on post-conflict societies and the creation of sustainable peace.

The full call for papers can be read here. Submissions should include an abstract of no more than 300 words and be accompanied by a CV. Please indicate for which seminar the abstract is intended. Submissions must be written in English and sent to j [dot] m [dot] iverson [at] cdh [dot] leidenuniv [dot] nl and j [dot] s [dot] easterday [at] cdh [dot] leidenuniv [dot] nl no later than 27 January 2014.

- The second event being hosted by the Grotius Center, Property and Investment in Contemporary Jus Post Bellum: Clarifying Norms, Principles and Practices is also seeking papers. This event will focus specifically on three main areas: (i) Housing, land and property of displaced persons, (ii) protection of culturally significant property, and (iii) investment. It will investigate how property and investment rights can be reconciled with other rights in the context of jus post bellum; and what approaches law are most likely to produce a just and sustainable peace.The full call for papers can be read here. Just as with the first seminar’s call for papers, submissions should include an abstract of no more than 300 words and be accompanied by a CV. Please indicate for which seminar the abstract is intended. Submissions must be written in English and sent to j [dot] m [dot] iverson [at] cdh [dot] leidenuniv [dot] nl and j [dot] s [dot] easterday [at] cdh [dot] leidenuniv [dot] nl no later than 27 January 2014. Selected participants for both seminars will be informed 22 February 2014. Final papers should be submitted by 16 May 2014.

Events

- Max Planck Masterclass in International Law will take place from 29 April – 2 May 2014 in which Professor Martti Koskenniemi will discuss: Critical Studies of International Law. The scholarship of international law is often caught in the dichotomy between apologetic etatism and utopian humanism. No one has described this contraposition and its implications more clearly than Martti Koskenniemi, most prominently in “From Apology to Utopia” (1989). During the last decades, he has been preeminent in criticizing what he calls the “Kitsch” of international legal scholarship. He emphatically describes the perplexities and disputability of concepts such as human rights or the international community. Beside his contributions in the field of deconstructivist thinking, Martti Koskenniemi has also published several pieces with a historical take. To name again but one lighthouse publication, “The gentle civilizer” (2004) tells an insightful and critical story about the emergence of international law as part of liberal modernity. The number of participants is limited in order keep the character of a seminar. Please send your applications, including a letter of motivation and a CV, till 31 January 2014 to masterclass2014 [at] mpil [dot] de. During the Masterclass, one afternoon will be dedicated to presentations from participants. Whoever would be interested in presenting his or her work in that session, is invited to indicate so and to send a short abstract along with the application. On Thursday, 1 May 2014, Professor Koskenniemi is going to give a public lecture at the DAI Heidelberg (http://www.dai-heidelberg.de/), entitled “Sovereignty, Property and International Law. A Historical View”. Everybody is cordially invited to join for that lecture.

- The Hague University of Applied Sciences (HUAS) has announced an upcoming multidisicplinary conference entitled: Africans and Hague Justice: Realities and Perceptions of the International Criminal Court in Africa, from 23-24 May 2014 at the HUAS in The Hague. Professor Kamari M. Clarke (University of Pennsylvania) Professor Charles C. Jalloh (University of Pittsburg) and Professor Makau W. Mutua (SUNY Buffalo Law School) will be speaking during the conference. For more information and registration, please visit the conference website.

Last week’s events and announcements can be found here. If you would like to post an announcement on Opinio Juris, please contact us. Season’s Greetings to all our readers!

December 22nd, 2013 - 9:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Events and Announcements: December 22, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/22/events-announcements-december-22-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

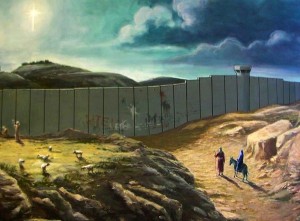

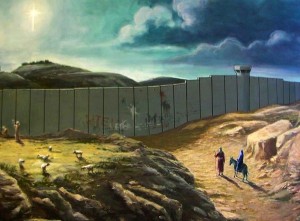

British artist Banksy knocks it out of the park again, with a rather unusual rendering of a Nativity scene:

As ArtInfo notes, this is not Banksy’s first comment on the Israel/Palestine conflict. He painted nine amazing murals directly on the wall in 2005, including a boy drawing a chalk ladder over the wall and a girl floating over the wall with a bouquet of balloons.

Is there a more brilliant and politically insightful artist working today than Banksy? I’m still blown away by the meat truck filled with wailing stuffed animals that he had driving around Manhattan. It’s one of the most powerful pro-vegetarian statements I’ve ever seen. Watch the video here.

December 22nd, 2013 - 6:36 AM EDT |

4 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/22/merry-christmas-banksy/ |

by Duncan Hollis

That’s the punchline of a podcast Radiolab just released this week, provocatively titled “Sex, Ducks and The Founding Feud”. Along with John Bellinger, Joseph Ellis and Nick Rosenkranz, I was interviewed for the story by Jad Abumrad and Kelsey Padgett. It was a fun experience overall trying to explain to a general audience the importance of the US treaty power and how it plays out in the Bond case, and Missouri v Holland before that. On the whole, I enjoyed hearing some fabulous sound editing (which is not surprising given Jad’s previous work won him a McArthur Genius award). Entertaining as it is though, I also found the piece quite thoughtful in framing the importance of the treaty power and offering both sides of the arguments, even if one might quibble over a few details here and there (eg the constitutionality of the implementing legislation versus that of the treaty).

Interested readers can take a listen here.

December 21st, 2013 - 12:38 PM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/21/love-greater-treaties/ |

by An Hertogen

This week Kevin briefly turned the blog into The Onion Juris with his satirical ICTY press release, after the Court, in Kevin’s opinion, nailed the final nail in the coffin of its legitimacy. In a guest post, Eugene Kontorovich framed the question as a design choice in terms of who should bear the risk when a judge becomes unavailable before a trial has ended.

Not satire was Kevin’s post about glitter territorism. Kevin also posted a surreply to Ryan Goodman on whether Amnesty International inflated universal jurisdiction numbers.

We ran a symposium on Kristina Daugirdas’ Congress Underestimated from the latest AJIL issue, with comments by Paul Stephan, Daniel Abebe, and David Gartner. Kristina’s reply is here.

Jessica rounded up the news, and I listed events and announcements.

Have a nice weekend!

December 21st, 2013 - 4:30 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekend Roundup: December 14-20, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/21/weekend-roundup-december-14-20-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

Oklahoma City police are obviously upset that the UK has pulled ahead of the US in the competition to have the most absurd definition of terrorism. Hence this:

On Friday, Oklahoma City police charged a pair of environmental activists with staging a “terrorism hoax” after they unfurled a pair of banners covered in glitter—a substance local cops considered evidence of a faux biochemical assault.

Stefan Warner and Moriah Stephenson, members of the environmental group Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance, were part of a group of about a dozen activists demonstrating at Devon Tower, the headquarters of fossil fuel giant Devon Energy. They activists were protesting the company’s use of fracking, its role in mining of Canada’s tar sands, and its ties to TransCanada, the energy company planning to construct the Keystone XL pipeline. As other activists blocked the building’s revolving door, Warner and Stephenson hung two banners—one a cranberry-colored sheet emblazoned with The Hunger Games “mockingjay” symbol and the words “The odds are never in our favor” in gold letters—from the second floor of the Devon Tower’s atrium.

Police who responded to the scene arrested Warner and Stephenson along with two other protesters. But while their fellow activists were arrested for trespassing, Warner and Stephenson were hit with additional charges of staging a fake bioterrorism attack. It’s an unusually harsh charge to levy against nuisance protestors. In Oklahoma, a conviction for a “terrorist hoax” carries a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

Oklahoma City police spokesman Captain Dexter Nelson tells Mother Jones that Devon Tower security officers worried that the “unknown substance” falling from the two banners might be toxic because of “the covert way [the protesters] presented themselves…A lot were dressed as somewhat transient-looking individuals. Some were wearing all black,” he says. “Inside the banners was a lot of black powder substance, later determined to be glitter.” In their report, Nelson says, police who responded to the scene described it as a “biochemical assault.” “Even the FBI responded,” he adds. A spokesman for Devon Energy declined to comment.

Nothing quite says terrorism like transient-looking individuals wearing black. And, of course, we have all been deeply unsettled by new black anthrax that’s all the rage with al-Qaeda youth today.

Ain’t glitter terrorism fabulous?

December 19th, 2013 - 8:57 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Glitter, the New Anthrax http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/19/glitter-new-anthrax/ |

by Eugene Kontorovich

[Eugene Kontorovich is a Professor of Law at Northwestern University School of Law.]

What should an international court do when the judges hearing a case are not around to decide it, as has happened on the ICTY in the Seselj case that Kevin has written about?

The death or serious illness of an international judge during the pendency of a case is an entirely foreseeable matter. International criminal trials are quite long (an average of three years from the start of trial to judgement). At the ICTY, the length can be as long as nine years. The average age of judges on the Court is 62 at appointment. See the Realities of International Criminal Justice for these and other figures.

Given that proceedings are long and judges old, an empty seat on the bench should, from an institutional perspective, not be a surprise. The best way to deal with this, if one is concerned about the issue, is the designation of alternate judges. This happened at Nuremberg, and is provide for in Art 74(1) of the Rome Statute, and in the Special Courts for Sierra Leone and Lebanon, where they “shall be present at each stage of the trial or appeal to which he or she has been designated.”

So the lack of a provision for such supernumeraries is a design choice or error. Certainly alternates burden an already expensive system. On the other hand, alternates are a known form of “insurance” for the continuance and integrity of international criminal trials.

So the question is who should bear the risk if the Tribunal does not “purchase” such insurance and the feared contingency occurs – the defendant or the Court (and perhaps justice). The general principle of strict construction in favor of the defendant in criminal matters would suggest imposing the costs on the Court, and yes, on international justice, which is more risk-averse (diversified across multiple cases).

Most fundamentally, because it is the officers of the Court that can best avoid such problems (by expediting proceedings) the consequences should fall on them. Of course, one does not wish to encourage hurried proceedings. So if the cost of such errors is seen as unacceptably high, alternates should be provided for in the future, or the rules requiring judicial presence relaxed.

December 18th, 2013 - 4:10 AM EDT |

3 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/18/guest-post-kontorovich-missing-judges-design-choice/ |

by Kristina Daugirdas

[Kristina Daugirdas is Assistant Professor of Law at Michigan Law]

First off, I would like to thank Paul, Daniel, and David for their very thoughtful comments. I’m glad to have the opportunity to respond to some of the key points that they made.

Paul provocatively suggested that perhaps we should care about results rather than democratic accountability per se. If a particular set of institutional arrangements actually improves human lives, maybe it’s of secondary importance whether those institutional arrangements are anti-democratic. Put in the terms of my article, the question wouldn’t be whether the World Bank suffers from a democratic deficit, but whether Congress’s participation in setting World Bank policy advances the Bank’s efforts to rid the world of poverty.

That’s a challenging question. Many government and Bank officials decry Congress’s meddling, arguing that it politicizes the Bank, that coping with congressionally-created financial crises detracts resources and staff time away from the Bank’s core mission, and that Congress’s interventions amplify the Bank’s tendency to cater to members who contribute funds at the expense of members who borrow them. Those are serious concerns. At the same time, the U.S. Congress was a forceful advocate of some innovations in the Bank’s operations that are widely praised, including the establishment of the World Bank Inspection Panel. The voting rules at the World Bank ensure that only those proposals that are able to gain the support of a range of member states are translated into World Bank policy. The obviously parochial legislated instructions that could impede the Bank’s efforts to support development are typically dead on arrival.

Both Daniel and David ask whether the dynamics the article describes in the World Bank context are likely to carry over to other international organizations, especially those that are more central to foreign affairs. Isn’t the conventional wisdom about the President’s dominance in foreign affairs, Daniel asks, really a story about high-salience foreign-affairs issues? Well, kind of. It’s certainly right that “foreign affairs” is often equated, explicitly or implicitly, with war and national security. But one of the points I hoped to emphasize is that this is an increasingly outdated and misleading perception of what “foreign affairs” encompasses. Today, nearly every federal regulatory regime has an international counterpart of some kind. To name just a few, there are international agreements that address wetlands protection, financial institutions, and food safety standards. If we want to understand the dynamics between the political branches in foreign affairs, we would be seriously remiss to ignore the vast realm of lower-salience issues.

The narrower question nonetheless stands: Continue Reading…

December 17th, 2013 - 1:00 PM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/17/ajil-symposium-reply-kristina-daugirdas/ |

by David Gartner

[David Gartner is Professor of Law at Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University]

In Congress Underestimated, Kristina Daugirdas offers a valuable new perspective on the role of the Congress in shaping the foreign relations of the United States with respect to international institutions. The article presents a fascinating case study of the assertive role of the Congress in influencing executive branch positions towards the World Bank and offers an interesting counter-example to the idea that the President reigns supreme in contemporary foreign relations. In these comments, I want to address two important questions raised by the article: First, is it right that Congress has been underestimated with respect to its influence over the World Bank? Second, is the World Bank case exceptional or does it reflect a more generalizable conclusion about the role of Congress in shaping US policy towards international institutions?

Daugirdas argues that leading accounts of Congress as a feeble participant in foreign affairs have underestimated its influence over US participation in the governance of the World Bank. She highlights the ways in which Congress has used its power of the purse to impose conditions on funding and give directives regarding the positions taken by the US Executive Director of the World Bank. Across Presidential administrations and in times of both unified and divided government, the executive branch has largely followed these congressional instructions with respect to the World Bank. Although the article recognizes some limits to this influence, it captures an important source of congressional leverage even as it potentially overstates its ultimate impact on the day-to-day operations of the Bank.

Continue Reading…

December 17th, 2013 - 10:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on AJIL Symposium: Congress and the World Bank http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/17/ajil-symposium-congress-world-bank/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

PRESS RELEASE

(Exclusively for the use of the media. Not an official document)

The Hague, 25 December 2013

MS/PR1593e

Acquitted defendants to be immediately apprehended and executed

The Trial Chamber on Saturday issued a decision on the status of the freedom of individuals acquitted by the Tribunal. The Chamber unanimously ordered all such individuals immediately apprehended and executed.

The Chamber’s order is made pursuant to Rule 54 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, which provides that “[a]t the request of either party or proprio motu, a Judge or a Trial Chamber may issue such orders, summonses, subpoenas, warrants and transfer orders as may be necessary for the purposes of an investigation or for the preparation or conduct of the trial.” The Trial Chamber rejected the argument of counsel for acquittees Ante Gotovina and Momčilo Perišić, made in an October 31 motion, that Rule 54 did not apply to the post-trial phase of a case and, in any event, did not permit the Chamber to order the execution of an acquitted individual. The Chamber noted that “the trial” could be fairly read to include the post-judgment phase and pointed out that the Rule provided the Chamber with broad discretion to do whatever is “necessary.”

The Chamber also rejected the claim of defence counsel that Art. 14(3) of the Statute, which provides that “[t]he accused shall be presumed innocent until proved guilty,” prohibited post-acquittal execution. The Chamber held that the provision did not apply, because an individual acquitted by the Tribunal could no longer be considered an “accused.” The Chamber equally disagreed with the claim that the decision countenanced summary execution, noting that it had carefully considered the merits of the issue and that, as judges, the Chamber would never countenance any action that was inconsistent with the rights of the defence.

Finally, the Chamber emphasized that today’s decision was consistent with the object and purpose of the Statute, which is to combat impunity. “The Chamber cannot permit individuals to avoid justice through technicalities such as acquittal,” the judges wrote.

The Office of the Prosecutor issued a statement in support of today’s decision, citing Churchill’s suggestion that high-ranking Nazis be rounded up and shot as precedent for the Trial Chamber’s order. It also immediately filed a motion with the Trial Chamber asking it to prospectively apply the order to current trials, in the unlikely event that guilty defendants such as Karadžić or Mladić are acquitted.

PS. No actual acquitted individuals were harmed in the making of this post, which is satire. Alas, the reasoning that it makes fun of is all too real. See here, for example.

December 16th, 2013 - 9:51 PM EDT |

8 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/breaking-icty-orders-immediate-execution-acquitted-defendants/ |

by Daniel Abebe

[Daniel Abebe is Professor of Law and Walter Mander Teaching Scholar at the University of Chicago]

In Congress Underestimated: the Case of the World Bank, Professor Daugirdas studies the World Bank to gain better traction on two important debates in the foreign affairs law literature, namely the extent to which the President, vis-à-vis Congress, is dominant in foreign affairs and the claim that international organizations like the World Bank weaken democracy by enfeebling domestic legislatures. As I understand it, her argument is that contrary to the conventional wisdom of presidential dominance, Congress has used the threat of reduced World Bank funding and specific voting instructions to force the President to at least embrace, if not implement, Congress’s preferences. Moreover, Congress’s influence on U.S. policy at the World Bank challenges the view that international organizations undermine democracy by enfeebling Congress’s capacity to influence policy outcomes. If correct, her overall argument challenges existing conceptions of the relationship between the President and Congress in foreign affairs, and complicates our understanding of the interaction between domestic legislatures and international organizations.

Congress Underestimated: the Case of the World Bank is filled with rich institutional detail about the World Bank’s internal operations and the negotiations between Congress and the President over World Bank policy. Although much of the detail warrants discussion, due to the space constraints of a blog post I will focus my comments on the two related arguments and the evidence offered in support. Let me start with the presidential dominance claim and move from there.

Continue Reading…

December 16th, 2013 - 2:00 PM EDT |

Comments Off on AJIL Symposium: Comments by Daniel Abebe on “Congress Underestimated” http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/ajil-symposium-comments-daniel-abebe/ |

by Paul Stephan

[Paul B. Stephan is the John C. Jeffries, Jr., Distinguished Professor of Law and David H. Ibbeken ’71 Research Professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.]

Many scholars believe that a shift of authority to international organizations benefits the Executive Branch more than Congress. The Executive interacts directly with these organizations and bears undiluted accountability for the consequences of their actions. Congress deals with them sporadically and has weak institutional interests. Members are elected by local, rather than national, constituencies and therefore have an incentive to focus on local rather than national effects of foreign affairs, the actions of international organizations included. Therefore, some have suggested (myself included), Executive Branch actors might prefer international delegations as a means of hobbling legislative oversight. To oversimplify greatly, people like me have argued that internationalists who wish to deepen and broaden international cooperation through institutions might find themselves playing into the hands of the Imperial Presidency.

Kristina Daugirdas’s excellent article pushes back against the widely held belief that international institutions augment Executive power at the expense of Congress. Rather than theorize, she does research. Her careful study of the history and pattern of legislative oversight of the World Bank demonstrates the Congress has the capacity effectively (and significantly) to influence U.S. policy toward the Bank, and even to alter the Bank’s behavior. Creation of the Bank did not lead to a surrender of the legislature’s prerogatives, but rather gave members (especially in the House) a new pressure point for extracting concessions from the Executive.

The key factor that enables Congress to ride herd on the Bank, Daugirdas observes, is the Bank’s need for periodic new funding. This was not always true, as the Bank was designed to generate a positive return on its founding capital. The creation of a more aggressively redistributionist institution in the form of the International Development Association in 1960 changed this dynamic, because the IDA depends on frequent infusions of new capital. Because Congress must approve any U.S. contributions, it can hold the funding hostage to its policy preferences. Moreover, it has demonstrated an ability to monitor the Bank and thus to respond to slippage between its instructions and the Bank’s performance. In early years, when Congress instructed the U.S. Executive Director not to vote in favor of certain loans, the U.S. representative behaved as required but did nothing to alter the votes of other Directors. After Congress responded through more aggressive pressure on the funding lever, the Bank shifted course.

Although the need for regular funding is the salient variable, also important is the role of departmentalism within the Executive Branch. The White House, with its own agenda as well as acting as the focal point for all the Executive’s components to express their interests, may have a particular policy, but the Treasury has the responsibility for managing the United States’s relationship with the Bank and deals regularly with Congress. When Congress has been unhappy, Daugirdas shows, it focuses its displeasure on Treasury, which in turn works hard to steer the Bank’s behavior in the direction Congress wants, whatever the White House might prefer.

This article does several wonderful things. Continue Reading…

December 16th, 2013 - 12:00 PM EDT |

Comments Off on AJIL Symposium: Congressional Oversight of International Organizations http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/ajil-symposium-congressional-oversight-international-organizations/ |

by An Hertogen

Today and tomorrow, we are joining forces again with the American Journal of International Law to bring you a discussion of Kristina Daugirdas‘ article, “Congress Underestimated”:

Using the World Bank as a case study, this article casts doubt on the empirical foundation for the claim that international organizations undermine democracy by undermining legislatures, at least in the United States. The article also argues that the conventional wisdom about the executive branch’s dominance in foreign affairs may be overstated—especially outside the context of wars and crises. Over the past forty years, Congress has undertaken persistent and often successful efforts to shape day-to-day U.S. participation in the World Bank, a key international organization.

Congress has relied on a combination of tools to accomplish this. It has adopted legislation instructing the U.S. representative at the World Bank to oppose specified categories of loans and pursue specified policies. It has credibly threatened to cut appropriations. And it has stepped up its monitoring of both the World Bank and the executive branch’s interactions with it. The President has objected that Congress’s legislated instructions contravene constitutional limits on its authority. But these protestations have not held Congress back. The Treasury Department—the executive branch agency that implements U.S. policy with respect to the Bank—has diligently followed Congress’s instructions to ensure that Congress continues to provide necessary appropriations.

By focusing on Congress’s ongoing role in influencing the World Bank’s operations, this article addresses a perplexing oversight in the literature concerning the democratic accountability of international organizations in the United States. To the extent that this literature considers Congress at all, it has focused narrowly on two discrete points: Congress’s role in the initial decision to authorize U.S. participation in international organizations and its role in implementing new international legal obligations that these organizations generate. But limiting the inquiry to these discrete points misses much of what is important. First, international organizations are durable institutions with long lives; the World Bank, for example, has been around since 1945. Concerns about democratic accountability do not wane over time. To the contrary, they are likely to grow more acute. Second, many international organizations, including the World Bank, conduct their mandated activities without generating new international norms that bind their member states, with the consequence that their activities do not raise the question of whether implementing legislation is necessary.

Commentators are Paul Stephan (Virginia), Daniel Abebe (Chicago) and David Gartner (Arizona State). As always we welcome readers’ comments!

December 16th, 2013 - 10:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on AJIL Symposium on “Congress Underestimated” by Kristina Daugirdas http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/ajil-symposium-congress-underestimated-kristina-daugirdas/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Your weekly selection of international law and international relations headlines from around the world:

Middle East

Asia

Africa

Europe

Americas

December 16th, 2013 - 6:45 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekly News Wrap: December 16, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/weekly-news-wrap-december-16-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

So, it’s official: the ICTY Trial Chamber has decided to let Judge Niang replace Judge Harhoff on the Seselj case:

The Trial Chamber on Friday issued a decision on the continuation of the proceedings in the case of Vojislav Šešelj, following the disqualification of Judge Frederik Harhoff and appointment of Judge Mandiaye Niang to the Bench.

The Chamber unanimously ordered that the proceedings would resume from the point after the closing arguments, and move into the deliberations phase as soon as Judge Niang has familiarized himself with the file. The Trial Chamber will issue a decision once this has been completed.

The Chamber agreed that a new judge is able to assess witness testimony given in his absence through other means, including video recordings. Consequently, the Chamber concluded that Judge Niang will be thus able to evaluate the credibility of witnesses heard during the proceedings in the Šešelj case, and familiarise himself with the record of the proceedings to a satisfactory degree.

[snip]

The Prosecution argued that that the trial should continue at the deliberation stage, after Judge Niang familiarises himself with the existing case record. The Prosecution claimed that such a solution would not be unprecedented in the Tribunal’s practice, pointing to the trial of Slobodan Milosevic where Judge Bonomy replaced Judge May.

The ICTY has yet to release an English translation of the decision, but Dov Jacobs notes on twitter that the Trial Chamber claims allowing Judge Niang to participate in deliberations, despite not hearing a single witness or item of evidence, is “in the interest of justice.” By “in the interests of justice,” of course, the Trial Chamber means “in the interests of conviction,” because there is nothing remotely just about permitting a judge to decide the fate of an individual whose trial he did not attend for even a single day.

Alas, that is only one of many absurdities in the case. As I have pointed out before, the Tribunal is appointing Judge Niang pursuant to a rule of procedure, Rule 15bis, that applies only to “part heard” cases. But applying the rule as written would prevent Seselj from being convicted, so the Tribunal is simply ignoring what it says. And, of course, the OTP is playing its part by invoking the dreaded Milosevic case as precedent, conveniently ignoring the fact that Judge Bonomy was appointed to replace Judge May before the defence began its case in chief, a situation that — unlike Seselj’s — is actually covered by Rule 15bis.

But don’t worry, Judge Niang is supposedly going to spend the next six months “assess[ing] witness testimony given in his absence through other means, including video recordings,” and will thus be able to “familiarise himself with the record of the proceedings to a satisfactory degree.” Of course he will: it’s not like the trial lasted 175 days, involved 81 witnesses, included 1,380 exhibits, and generated more than 18,000 pages of trial transcript (a mere 100 pages of transcript per day, assuming Judge Niang never takes a day off and fits his reading in around the hundreds of hours of witness testimony he will need to watch).

I’ve always defended the legitimacy of the ICTY — even after experiencing first-hand in the Karadzic case how unfair the Tribunal can be at times. But no longer. Unless the Appeals Chamber does the right thing, this latest decision will forever tarnish both the ICTY’s legacy and international criminal justice more generally.

December 16th, 2013 - 6:37 AM EDT |

Trackbacks(1) | 20 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/16/final-nail-ictys-coffin/ |

by An Hertogen

- Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Freie Universität Berlin have announced a new joint 3-year interdisciplinary Doctoral Program entitled “Human Rights under Pressure – Ethics, Law and Politics” (HR-UP), funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Einstein Foundation Berlin. HR-UP offers young researchers a unique opportunity to conduct cutting-edge research on the most pressing contemporary challenges for human rights, including issues arising from crises and emergencies, globalization and diversity. Doctoral researchers admitted to the program will receive competitive fellowships and mobility funds for research terms at the partner university. They will be jointly supervised by senior researchers from Germany and Israel, and participate in both jointly and locally held courses, including a two-week introductory intensive course in Jerusalem, joint interdisciplinary colloquia, research ‘master-classes’, and three annual summer schools in Berlin. The program also includes two post-doctoral positions (one in each university). The deadline for applications is January 27th, 2014. For further information, and to apply, please visit www.hr-up.net.

- The Third Conference of the Postgraduate and Early Professionals/Academics Network of the Society of International Economic Law (PEPA/SIEL) will take place in São Paulo (Brazil), on April 24-25, 2014, in cooperation with DIREITO GV – São Paulo Law School. This conference offers postgraduate students (students enrolled in Masters or PhD programmes) and early professionals/academics (generally within five years of graduating) studying or working in the field of International Economic Law an opportunity to present and discuss their research. It also provides a critical platform where participants can test their ideas about broader issues relating to IEL. One or more senior practitioners or academics will comment on each paper after its presentation, followed by a general discussion. Interested students should e-mail a CV and a research abstract (no more than 400 words) no later than January 12, 2014. More information is here.

- The Institute of Advanced Legal Studies at the University of London is organising a workshop on National Security and Public Health as exceptions to Human Rights on May 29, 2014 and is now calling for papers. All the information and the call for papers can be found here:here.

- If you’re looking for a stocking stuffer for the international law geek in your life, the International Game of Justice developed by Valentin Jeutner, a PhD student at Gonville and Caius College, at the University of Cambridge, may be just what you are looking for. More information is here.

Last week’s events and announcements can be found here. If you would like to post an announcement on Opinio Juris, please contact us.

December 15th, 2013 - 10:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Events and Announcements: December 15, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/15/events-announcements-december-15-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

In my previous post, I questioned Ryan’s claim that Amnesty International’s totals concerning the number of states exercising universal jurisdiction over at least one international crime “may be significantly inflated.” I pointed out that, contrary to what he was asserting, the report did not count a state simply because it it had incorporated the Rome Statute into its domestic legislation; on the contrary, in every case it identified the specific legislative provision(s) that extended universal jurisdiction over one or more international crimes.

Ryan has replied to my post. Here is the core of his response:

Kevin agrees with one aspect of my argument. He writes, “As Ryan rightly points out, the Rome Statute is neither based on universal jurisdiction nor requires states that implement it to adopt universal jurisdiction.”

Kevin, however, disagrees with another aspect. But this disagreement is based on a misunderstanding of my argument. I accept responsibility as an author for any lack of clarity. Kevin writes, “Amnesty does not seem to be suggesting that implementing the Rome Statute simpliciter is enough to consider a state to have universal jurisdiction over the international crimes therein.”

Kevin thinks I disagree with that description. But I agree with it.

Ryan does not explain how I misunderstood his argument, and I fail to see how I did. If he does not believe Amnesty is overcounting states in its study by including those that merely incorporate the Rome Statute, what is the basis for his claim that Amnesty’s numbers are “significantly inflated”? After all, the title of his original post is “Counting Universal Jurisdiction States: What’s Wrong with Amnesty International’s Numbers.” And why did he write “Here’s what troubles me: Amnesty International appears to count states as having enacted universal jurisdiction… if the state has adopted a form of implementing legislation along with ratification of the treaty”?

Confused about what I got wrong, I asked Ryan on twitter whether he was withdrawing his claim that Amnesty’s universal-jurisdiction numbers are “significantly inflated.” He said he was not. So he still believes that at least some non-negligible number of states that Amnesty counts in its study do not, in fact, exercise universal jurisdiction over at least one international crime.

That is an empirical claim, and one that Ryan has not supported. He has yet to cite even one state that he believes Amnesty wrongly included in its study — much less enough states to justify his claim that Amnesty’s numbers are “significantly inflated.”

December 14th, 2013 - 5:20 PM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/14/surreply-ryan-goodman-universal-jurisdiction/ |

by An Hertogen

This fortnight on Opinio Juris, Deborah reminisced about her handshake with Nelson Mandela during her time as a junior White House staffer and Roger posted about the day Mandela was free.

Mandela’s example was invoked at the WTO Ministerial Conference in Bali, where trade ministers reached their first trade agreement in years. Julian argued that the WTO however does not need the Bali Package for its dispute settlement system to remain relevant and Duncan discussed whether the Bali Package requires US Congressional approval. In other WTO news, Roger discussed how the WTO Dispute Panel in its recent EU-Seal Products decision recognized the self-judging nature of the public morals exception in article XX:a GATT.

Trade issues have inspired recent political protests in Ukraine, which Chris used to illustrate how geopolitics has become normative, and how all normative geopolitics is local. Chris also asked where international law should go now that life is imitating the art of political science fiction.

Kevin noted the OTP’s remarkable slow-walking of the Afghanistan examination. A series of articles on Judge Harhoff’s resignation also confirmed to Kevin-once he stopped fuming about the persistent misquoting of the Perisic judgment-that the Judge needed to be removed from the Seselj case. Kevin also assessed Ryan Goodman’s argument that Amnesty International has overstated the number of states that have implemented universal jurisdiction in its report on the issue.

Julian covered various topics that we have known him for recently. He noticed how Russia’s non-compliance with the ITLOS Artic Sunrise order went unnoticed in most media, and concluded that states do not take a reputational hit in case of non-compliance. Julian followed up on earlier posts regarding China’s ADIZ, and argued that the US position is not backed up by a coherent international legal framework. You can also see Julian in action in this video from a Cato Institute event on Argentina’s Debt Litigation and Sovereignty Immunity. On a lighter note, Julian also pondered how the US and Canada could legally merge, and pointed out the happy news that Santa has a visa waiver to enter the US.

Following the recent diplomatic success of the P5+1 and Iran, Sondre Torp Helmersen revisited the impact of the Iran hostage crisis for diplomatic law. Kristen focused on the effect of the deal for UN, rather than unilateral US and EU, sanctions on Iran.

In other organizational news, Kristen updated us on recent developments in Bluefin Tuna management.

Finally, Jessica and I listed various events and announcements that came to our attention (1, 2), and Jessica wrapped up the news headlines (1, 2).

Have a nice weekend!

December 14th, 2013 - 4:50 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekend Roundup: November 30-December 13, 2013 http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/14/weekend-roundup-november-30-december-13-2013/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

Not long ago, Amnesty International released an updated version of its massive study “Universal Jursidiction: A Preliminary Survey of Legislation Around the World.” The report concluded, inter alia, that 86% of the world’s states exercise universal jurisdiction over at least one kind of international crime. (Most commonly, war crimes.)

In a post today at Just Security, my friend and regular sparring partner Ryan Goodman suggests that Amnesty’s number “may be significantly inflated” (emphasis added):

Here’s what troubles me: Amnesty International appears to count states as having enacted universal jurisdiction if the state is a party to the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court or, more precisely, if the state has adopted a form of implementing legislation along with ratification of the treaty. Amnesty makes that decision on the stated assumption that the Rome Statute implicitly requires member states to adopt universal jurisdiction corresponding to its core crimes.

As Ryan rightly points out, the Rome Statute is neither based on universal jurisdiction nor requires states that implement it to adopt universal jurisdiction. That said, I do not believe Amnesty is doing what Ryan says it is — considering a state to have universal jurisdiction over a crime simply because it has incorporate the Rome Statute into its domestic legislation. In defense of that claim, Ryan cites a paragraph from the study’s methodology section (p. 9):

Crimes defined in national law, with reference to treaties.

In some instances, the state has defined a crime under international law, such as genocide, as a crime in national law and provided that its courts have jurisdiction over crimes in treaties it has ratified (some provisions do not specify that the treaty has to have been ratified). In those instances, the state would have jurisdiction not only over crimes in aut dedere aut judicare treaties, but treaties like the Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention) and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute) that do not contain an express obligation to exercise universal jurisdiction, although they may contain an implied obligation to do so. Annex I indicates that the state has jurisdiction over the relevant crime (YES).

This paragraph is not a picture of clarity, but Amnesty does not seem to be suggesting that implementing the Rome Statute simpliciter is enough to consider a state to have universal jurisdiction over the international crimes therein. What the paragraph says, I think, is that some states adopt universal jurisdiction legislation that does not specifically mention international crimes (e.g., State X shall have universal jurisdiction over genocide), but instead applies universal jurisdiction to any crime defined in a treaty ratified by that state — a much broader formulation.

More importantly, the report’s country-by-country analysis (Annex II) does not indicate that Amnesty counts a state as a universal jurisdiction state simply because it has incorporated the Rome Statute into its domestic legislation. On the contrary, the report always paraphrases the specific language in domestic legislation that supports the existence of universal jurisdiction. Consider three states — France, Kenya, and South Africa — all of which have incorporated the Rome Statute:

France

– art. 689-11 (anyone may be prosecuted by French courts who habitually resides on French territory and is responsible for one of the crimes within the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court – genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes – committed abroad, if the acts are punishable in the state where committed or if that state or the state of the person’s nationality is a party to the Rome Statute, provided that the prosecution was requested by the relevant minister, and that this official has verified that the International Criminal Court has expressly declined jurisdiction and that no international criminal court has requested surrender and no state has requested extradition)

Kenya

– International Crimes Act 2008, s. 8 (war crimes in International Crimes Act, s. 6 if the person is, after commission of the offence, present in Kenya) Crimes against humanity: International Crimes Act 2008, s. 8 (crimes against humanity in International Crimes Act 2008, s. 6 if the person is, after commission of the offence, present in Kenya) Genocide: International Crimes Act 2008, s. 8 (genocide in International Crimes Act 1959, s. 6 if the person is, after commission of the offence, present in Kenya)

South Africa

War crimes: ICC Act 2002, ss. 4 and 5 (provided that the person, after the commission of the crime, is present in the territory of the Republic and that the National Director authorises the prosecution) Crimes against humanity: ICC Act 2002, ss. 4 and 5 (see war crimes) Genocide: ICC Act 2002, ss. 4 and 5 (see war crimes)

If there are any Amnesty readers out there, please feel free to settle the dispute!

December 13th, 2013 - 8:03 PM EDT |

Trackbacks(2) | 3 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2013/12/13/is/ |

by Kristen Boon

Most reporting on the nuclear agreement with Iran has tended to generalize about the types of sanctions and the impact of the deal on these various measures, so it would be easy to assume that United Nations sanctions are being eased or lifted, but this is not the case. The deal primarily eases unilateral sanctions by the United States and the European Union against Iran, leading to what is estimated to be around $7 billion in sanctions relief.

UN sanctions against Iran—found in resolutions 1737, 1747, 1803 and 1929—will only be assessed at the six-month mark, with an eventual goal (the so-called “comprehensive solution”) of lifting them within a year. In the near term, the only commitment with regard to UN sanctions is that no new nuclear-related UN Security Council sanctions be imposed.

This raises an important issue: how should UN sanctions be approached in the meantime?

Under Article 25 of the UN Charter, member states remain obligated to give effect to Security Council measures. The new deal with Iran has not altered the obligation to implement sanctions. But on this front, work remains to be done. Gaps in the implementation of UN sanctions against Iran, which have been in place since 2006, are pervasive. Dual-use items, such as goods, software, and technology that may be used for both civilian and military purposes, have been a particular problem. Interpretation of resolution language and implementation of general terms in specific contexts have also led to implementation problems. Finally, because information on sanctions busters can involve classified information, states are very careful about what they share and with whom they share it.

EU officials have made clear that they, too, will continue to strictly implement sanctions not affected by the deal. This strategy was in question due to a series of challenges to UN and EU targeted sanctions. Criteria developed by the European Court of Justice in the Kadi case (regarding sanctions under resolution 1267) now require far greater detail for listings, and indicate that listed individuals and entities must have an opportunity to challenge those listings as a matter of human rights. These ideas are now beginning to influence the design and expectations for other types of sanctions regimes. (For background on the July 2013 Kadi decision, see my earlier post on Opinio Juris.)