Archive for

January, 2014

by Julian Ku

[I am passing along this reminder of the upcoming registration deadline on behalf of ILA President Ruth Wedgwood since many of our readers are likely to attend this meeting.]

Register by February 7, 2014 to snap up the advantageous “Early-Bird Rate”– saving $160 over the walk-up rate– for the historic joint meeting between the 150-year-old global International Law Association and the American Society of International Law, running April 7-12, 2014. The festivities will take place at the International Trade Center, next to the Washington Mall, during the height of Washington’s lovely Cherry Blossom Season. Family members will enjoy the trip too, since the Trade Center is close to all the best tourist stops in the nation’s capital, including the National Gallery, the Air and Space Museum, the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument, the Spy Museum, the Kennedy Center and the list goes on. Incredible program of public and private international law debates is described at www.ila2014.org or www.asil.org/annualmeeting. Adjacent J.W. Marriott Hotel at 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue has conference room rates that are well below market for Cherry Blossom Time. Notables including judges of the International Court of Justice, the International War Crimes Tribunals, and Supreme Courts around the world will be at the ILA-ASIL Joint Meeting to engage in our robust debates.

January 31st, 2014 - 4:30 PM EDT |

Comments Off on Registration Deadline for This Year’s Joint ILA/ASIL Annual Meeting http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/31/registration-deadline-years-joint-ilaasil-annual-meeting/ |

by Julian Ku

Last March, I took the world media (and Alan Dershowitz) to task for some pretty poor reporting on the extradition issues raised in the Amanda Knox case. Based on the reporting from yesterday’s conviction (again) of Amanda Knox in an Italian appeals court in Florence, I’m glad to report that the news coverage of the extradition issue (as well as Dershowitz’s analysis of it) has improved a great deal. I’ll admit I’ve been co-opted by the media a little, since I have given quotes to several publications about the case (click here for obnoxious self promotion).

What bothered me about the reporting last year was the insistence by news outlets and even several legal commentators that Amanda Knox was facing double jeopardy because she was facing a conviction for the same crime for which she was previously acquitted (see this quote here from CNN’s legal analyst Sonny Hostin as an example of this confusion). There are three problems with this argument:

1) The US Italy Extradition Treaty does not actually bar extradition for double jeopardy in the U.S. Constitutional sense. All it does is bar extradition if the person being extradited has already been charged for the same crime in the state doing the extraditing. For instance, the treaty would bar extradition to Italy for Knox only if the U.S. had prosecuted her for the Kerchner* murder. Judge Friendly’s discussion in the 1980 Sindona v. Grant case of a similar provision in an earlier US-Italy Extradition treaty focuses solely on whether the US charges were the same as the Italian charges. See also Matter of Extradition of Sidali (1995) which interpreted an identical provision of the US-Turkey extradition treaty.

2) The US Constitution’s double jeopardy bar does not apply to prosecutions by the Italian government (or any foreign government). This seems pretty unobjectionable as a matter of common sense, but many commentators keep talking about the Fifth Amendment as if it constrained Italy somehow. For obvious reasons, the fact that the Italian trial does not conform in every respect to US constitutionally-required criminal procedure can’t be a bar to extradition because that would pretty much bar every extradition from the U.S. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in US v. Balsys seems to have settled this question with respect to the Fifth Amendment self-incrimination rule, and it should apply to double jeopardy as well.

3) In any event, the conviction, acquittal, and then conviction again is almost certainly not double jeopardy anyways. Knox was convicted in the first instance, than that conviction was thrown out on appeal. That appellate proceeding (unlike a US proceeding) actually re-opened all of the facts and is essentially a new trial. But it is still an appellate proceeding and in the US we would not treat an appellate proceeding that reversed a conviction as an acquittal for purposes of double jeopardy. Moreover, it would essentially punish the Italian legal system for giving defendants extraordinary rights of appeal and tons more due process than they would get in the U.S. If Knox had been convicted in the U.S, she could not have re-opened all of the evidence the way she did in Italy, and probably would have had a harder time getting her original conviction overturned. So it seems crazy to call “unfair” a legal system which actually gave Knox a completely new chance to challenge her conviction.

Most media coverage seems to get these points (sort of). I think they have done so because folks like Alan Dershowitz have finally read the treaty and done a little research (he now agrees with this analysis of the treaty above, more or less), and because the magic of the Internet allowed my blog post from last March to be found by reporters doing their Google searches. So kudos to the Opinio Juris! Improving media coverage of international legal issues since 2005!

One final note: the only way this “double jeopardy” argument matters is if this gets to the US Secretary of State, who has final say on whether to extradite. He might conclude that the trial here was so unfair (because it dragged out so long) that he will exercise his discretion not to extradite. But this would be a political judgment, not a legal one, more akin to giving Knox a form of clemency than an acquittal. I would be surprised if the State Department refuses to extradite Knox, given the strong interest the U.S. has in convincing foreign states to cooperate on extradition. But Knox appears to have lots of popular support in the US. This may matter (even if it shouldn’t).

*The original post incorrectly called the murder victim “Kirchner”.

January 31st, 2014 - 9:58 AM EDT |

30 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/31/hows-media-amanda-knox-reporting-much-better-started-quoting/ |

by Chris Borgen

Following up on my earlier posts on the normative aspects of the struggle concerning Ukraine and other former Soviet countries (1, 2, 3) in the run-up to, and the aftermath of, the EU’s November summit in Vilnius, where Ukraine had been expected to sign an Association Agreement with the EU. However, the Yanukovich regime backed out at the last minute. I want to focus on recent developments in what analysts are calling the “post-Vilnius” atmosphere and what they reflect about how states and citizens compete over norms.

First, there is the spread of protests from the relatively pro-EU western Ukraine into the relatively pro-Russia eastern Ukraine. Electoral maps of Ukraine (1, 2) show the ideological division and why Ukraine is an example of what I’ve called a systemic borderland. The fact that the anti-government protests moving eastward across the map may be a sign of an increasing tilt towards following the original path of the government in seeking closer association with the EU. But it also may be nothing more that the populace being tired and angry of the political gridlock and motivated by pictures of anti-protestor violence in the western cities. In this latter scenario, the citizens in eastern Ukraine still want to be more closely tied with Russia, they are just sick of their government brutalizing their own people, for whatever the reason. News reports about protests are one thing, but understanding why people are protesting is very important in situations concerning whether or not domestic norms are in play.

I haven’t seen any significant data on whether there is a deeper normative shift taking place or whether the eastern protests are primarily a reaction to offensive government tactics.

The second development of note is the broadening of the Russia/ EU tensions. The New York Times article on this issue from the January 28 online edition is well worth a full read. Here are a few key points related to the normative aspects of the post-Vilnius tensions:

The future of Ukraine and disagreements over how Russia and EU have approached this are the drivers of the current international bickering. (Keep in mind the domestic tensions are also between the Ukrainian citizens and their government over how the Ukrainian government reacted to protests.) The international tensions stem from a concern about how Russia perceives its future, vis-à-vis Europe. From the Times:

Russia, [Michael Emerson, the former EU envoy to Moscow] said, needs to show that “all its talk about a ‘common European house’ from Lisbon to Vladivostok is not just a slogan and that Ukraine can be comfortable with both the E.U. and Russia.”

In short: is there one Europe or two? Will Ukraine be a bridge uniting Europe or a border between two normatively distinct Europes? A related issue is whether Russia even wants to explore deepening ties with the EU. The Times continues… (Continue Reading)

January 30th, 2014 - 11:03 AM EDT |

3 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/30/ukraine-protests-policy-papers-push-pull-normative-competition/ |

by Chris Borgen

I recently wrote a post that described the virtues of international lawyers thinking about the future and having an international law analog to “design fiction.” The main point being we as international lawyers are often so focused on historical examples, issues, and analogies that we need to spend more time considering the technological changes that are upon us and changing the world in which we live. A bit of tech futurism + international legal practice.

One of the best-known critiques of the profession considered the lack of imagination of the international legal profession. In 2001, Martti Koskeniemi wrote in The Gentle Civilizer of Nations that international law had been depoliticized and marginalized “as graphically illustrated by its absence from the arenas of today’s globalization struggles” or it had become “a technical instrument for the advancement of the agendas of powerful interests or actors in the world scene.” (page 3) He further wrote that international lawyers “in the past 40 years have failed to use the imaginative opportunities that were available to them, and open horizons beyond academic and political instrumentalization, in favor of worn-out internationalist causes that form the mainstay of today’s commitment to international law.” (page 5)

Now, having made a plea for a little more tech futurism in international law, I note that Professor Benjamin Bratton has just done a great job of taking the form of technological futurism most prevalent in TED conferences and smacking it upside the head a few times. Moreover, he did this in a sharp TEDx presentation (and an essay in The Guardian). I highly recommend watching the full TED talk. There’s a lot there that also applies to international legal profession.

Bratton describes the problem of “placebo politics”—focusing on technology and innovation as the solution to major world problems, but not taking into account the difficult issues of history, economics, and politics that bedevil actual workable solutions. Problems become oversimplified. He wrote in The Guardian:

Perhaps the pinnacle of placebo politics and innovation was featured at TEDx San Diego in 2011. You’re familiar I assume with Kony2012, the social media campaign to stop war crimes in central Africa? So what happened here? Evangelical surfer bro goes to help kids in Africa. He makes a campy video explaining genocide to the cast of Glee. The world finds his public epiphany to be shallow to the point of self-delusion. The complex geopolitics of central Africa are left undisturbed. Kony’s still there. The end.

You see, when inspiration becomes manipulation, inspiration becomes obfuscation. If you are not cynical you should be sceptical. You should be as sceptical of placebo politics as you are placebo medicine.

For more on Kony 2012, see our discussion of it, here.

Bratton continued:

If we really want transformation, we have to slog through the hard stuff (history, economics, philosophy, art, ambiguities, contradictions). Bracketing it off to the side to focus just on technology, or just on innovation, actually prevents transformation.

Instead of dumbing-down the future, we need to raise the level of general understanding to the level of complexity of the systems in which we are embedded and which are embedded in us. This is not about “personal stories of inspiration”, it’s about the difficult and uncertain work of demystification and reconceptualisation: the hard stuff that really changes how we think. More Copernicus, less Tony Robbins.

[Emphases added.]

International lawyers can be (but aren’t always) good at the facts on the ground, the messy realities of history, politics, economics. If my previous post was about how lawyers need to keep a weather eye on how new tech is changing the present and shaping the future, then Bratton reminds us how the technologists need to appreciate the hard realities of the present and to remember the lessons of past. In other words, each of us has a lot to learn from the other.

January 29th, 2014 - 10:10 AM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/29/ted-talks-placebo-politics-work-international-lawyers/ |

by Duncan Hollis

I’m pleased to flag the fact that the American Journal of International Law has recently launched its own blog — AJIL Unbound. Interested readers can find out more about the project and the Journal‘s interest in reader feedback here. In the meantime, AJIL Unbound is currently hosting an on-line discussion of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. in concert with the Journal‘s print-based Agora on that same case in its October 2013 issue. I look forward to reading these posts and also to seeing how AJIL Unbound develops and evolves in the weeks and months ahead.

January 28th, 2014 - 7:07 PM EDT |

Comments Off on Welcome to the Blogosphere AJIL Unbound http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/28/welcome-blogosphere-ajil-unbound/ |

by Anthony Colangelo

[Anthony Colangelo is Associate Professor of Law at SMU Dedman School of Law.]

As my comment to Roger’s initial post noted and my forthcoming piece in the Cornell Law Review explains, like Bill Dodge I view the presumption against extraterritoriality’s operation in Kiobel as going principally to the cause of action allowed by the ATS as opposed to the ATS proper. Though as Roger points out, the Supreme Court did find itself construing the ATS in order to discern whether the presumption applied to the cause of action, making an already messy area of law incoherent in light of the Court’s own most recent precedent, as I noted in an OJ Insta-Symposium contribution last spring.

What I’d like to explore now is another question raised by this terrific series of posts: the extent to which state law incorporating international law may authorize suits for causes of action arising abroad after Kiobel. This question is both especially urgent because it involves a potential alternative avenue for litigating human rights abuses abroad in U.S. courts, and especially vexing because it juxtaposes different doctrinal and jurisprudential conceptualizations of the ability of forum law to reach inside foreign territory. On the one hand, the question can be framed as whether forum law applies extraterritorially; on the other, it can be framed as a choice of law among multiple laws, of which forum law is one. These different ways of framing the question are not necessarily mutually exclusive, yet they can lead to radically different results. Namely, Supreme Court jurisprudence stringently applying a presumption against extraterritoriality to knock out claims with foreign elements stands in stark contrast to a flexible cadre of state choice-of-law methodologies that liberally apply state law whenever the forum has any interest in the dispute.

The result is a counterintuitive disparity: state law enjoys potentially greater extraterritorial reach than federal law. The disparity is counterintuitive because the federal government, not the states, is generally considered the primary actor in foreign affairs. Indeed, the presumption against extraterritoriality springs directly from foreign affairs concerns: its main purpose is to avoid unintended discord with other nations that might result from extraterritorial applications of U.S. law. If the federal government is the primary actor in foreign affairs, and if the presumption operates to limit the reach of federal law on a foreign affairs rationale, it follows that state law should have no more extraterritorial reach than federal law.

Yet at the same time there is a long and robust history stretching back to the founding of state law providing relief in suits with foreign elements through choice-of-law analysis. Hence, not only does the disparity between the reach of federal and state law bring into conflict federal versus state capacities to apply law abroad (or entertain suits arising abroad), it also brings into conflict the broader fields that delineate those respective capacities: foreign affairs and federal supremacy on the one hand, which argue in favor of narrowing the reach of state law to U.S. territory, and private international law and conflict of laws on the other hand, which argue in favor of allowing suits with foreign elements to proceed in state court under state law. Continue Reading…

January 28th, 2014 - 4:10 PM EDT |

2 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/28/guest-post-colangelo-kiobel-conflicts-law/ |

by William S. Dodge

[William S. Dodge is The Honorable Roger J. Traynor Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Research at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law. From August 2011 to July 2012, he served as Counselor on International Law to the Legal Adviser at the U.S. Department of State, where he worked on the amicus briefs of the United States in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. The views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the State Department or of the United States.]

The Supreme Court held in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 133 S. Ct. 1659 (2013), that the presumption against extraterritoriality applies to suits brought under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS). In a recent post, Roger Alford asks whether a federal court sitting in diversity or a state court of general jurisdiction may still hear the federal common law claims for torts in violation of the law of nations that the Court recognized in Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692 (2004). The answer depends on whether Kiobel applied the presumption against extraterritoriality to the ATS itself or to Sosa’s federal common law cause of action.

As a general matter, the presumption against extraterritoriality does not apply to jurisdictional statutes. Putting Kiobel to one side for the moment, I know of only two cases in which the Supreme Court has used the presumption to interpret statutes that might be characterized as jurisdictional. In Argentine Republic v. Amerada Hess Shipping Corp., 488 U.S. 428, 440-41 (1989), the Court applied the presumption to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, and in Smith v. United States, 507 U.S. 197, 203-04 (1993), it applied the presumption to the Federal Tort Claims Act. But both the FSIA and the FTCA codify rules of immunity, which the Court has characterized as substantive, and so neither statute is purely jurisdictional. No one suggests that the presumption against extraterritoriality limits 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (the federal question statute), or 28 U.S.C. § 1332 (the diversity and alienage jurisdiction statute), or 18 U.S.C. § 3231 (the subject matter jurisdiction statute for federal criminal offenses). Yet none of these jurisdictional provisions contain the clear indication of extraterritoriality that would be necessary to rebut the presumption. To take one example, if the presumption against extraterritoriality were applied to 18 U.S.C. § 3231, a federal court would have to dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction a federal prosecution for bombing U.S. government facilities abroad despite the fact that the substantive criminal statute (18 U.S.C. § 2332f) expressly applies when “the offense takes place outside the United States.” That makes no sense, and is not a result that any sensible court would reach.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010), confirms the distinction between substantive statutes to which the presumption against extraterritoriality applies and jurisdictional statutes to which it does not. In Morrison, the Court used the presumption to limit a substantive provision of the Securities Exchange Act, finding “no affirmative indication in the Exchange Act that § 10(b) applies extraterritorially.” Id. at 2883. But notably, the Court did not apply the presumption against extraterritoriality to the Exchange Act’s jurisdictional provision. To the contrary, the Court specifically held in Part II of its opinion that “[t]he District Court here had jurisdiction under 15 U.S.C. § 78aa to adjudicate the question whether § 10(b) applies to National’s conduct,” id. at 2877, despite the fact that § 78aa contains no clear indication of extraterritoriality, which would be needed to rebut the presumption if it applied.

Kiobel is consistent with the distinction that courts applying the presumption against extraterritoriality have long drawn between jurisdictional and substantive statutes. “We typically apply the presumption to discern whether an Act of Congress regulating conduct applies abroad,” the Court noted. 133 S. Ct. at 1664 (emphasis added). The ATS was not such a statute; the Sosa Court had held that it was “strictly jurisdictional.” But Sosa also held that the ATS authorized courts to recognize federal common law causes of action for torts in violation of the law of nations, and it was to those causes of action that the Supreme Court applied the presumption in Kiobel. “[W]e think the principles underlying the canon of interpretation similarly constrain courts considering causes of action that may be brought under the ATS.” Id. (emphasis added). Thus, after reviewing the text and history of the ATS, the Court concluded “that the presumption against extraterritoriality applies to claims under the ATS, and that nothing in the statute rebuts that presumption.” Id. at 1669 (emphasis added).

To be clear, Continue Reading…

January 28th, 2014 - 12:00 PM EDT |

2 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/28/guest-post-dodge-presumption-extraterritoriality-apply-jurisdictional-statutes/ |

by Jonathan Hafetz

[Jonathan Hafetz is an Associate Professor of Law at Seton Hall University School of Law. This post is written as a comment to Stuart Ford’s guest post, published yesterday.]

Stuart Ford’s article, Complexity and Efficiency at International Criminal Courts, seeks to address the common misperception that international criminal trials are not only expensive, but also inefficient. Professor Ford’s article focuses principally on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which, in terms of the total number of accused, is the largest international criminal tribunal in history. Professor Ford seeks to measure whether the ICTY has, in effect, provided good bang for the buck. He concludes, rightly I believe, that it has. Although his primary aim is to develop a way for measuring a tribunal’s efficiency, Professor Ford’s article also has important implications for broader debates about the merits of international criminal justice.

Professor Ford defines efficiency as the complexity of a trial divided by its cost. While trials at the ICTY often have been long and expensive, they have also been relatively efficient given their complexity. Further, the ICTY preforms relatively well compared to other trials of similar complexity, such as terrorism trials conducted in the United States and Europe, as well as trials that are somewhat less complex, such as the average U.S. death penalty case. Garden-variety domestic murder trials, which at first blush might appear more efficient than the ICTY, do not provide a useful point of comparison because they are much more straightforward.

Once complexity is factored in, the ICTY appears comparatively efficient. Its record is more impressive considering that an often recognized goal of international criminal justice—creating a historical record of mass atrocities—can make the trials slower and less efficient in terms of reaching outcomes for specific defendants.

Professor Ford also finds that the ICTY performed more efficiently than the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), thus challenging a perceived advantage of such hybrid tribunals over ad hoc tribunals like the ICTY. His conclusion suggests the need for future research on comparisons among tribunals within the international criminal justice field, which might have implications from an institutional design perspective. Continue Reading…

January 28th, 2014 - 9:00 AM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/28/guest-post-hafetz-measuring-value-criminal-trial/ |

by Stuart Ford

[Stuart Ford is an Assistant Professor at The John Marshall Law School.]

It is common to see people criticize international tribunals as too slow, too expensive, and inefficient. Professor Whiting even argues this is now the consensus position among “policymakers, practitioners, and commentators (both academic and popular).” But are these criticisms accurate? At least with respect to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), I believe the answer is no.

Most of those who have criticized the ICTY are implicitly comparing the ICTY to trials in domestic courts. And indeed, ICTY trials take much longer than the average domestic criminal proceeding. For example, in 2011 nearly 70% of criminal trials in federal courts in the United States took one day or less to try and there were only 37 trials that lasted more than 20 days. See here at Table T-2. In comparison, the average ICTY trial has lasted 176 days. So, it is true that trials in the U.S. are much quicker than trials at the ICTY, but it is also true that ICTY trials are vastly more complex than the average domestic trial, and we generally expect more complex trials to be more expensive. As a result, it is misleading to compare the cost and length of the ICTY’s trials to those in other courts without first accounting for the complexity of those trials.

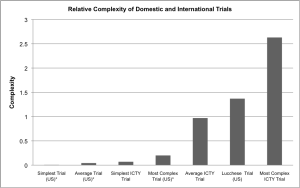

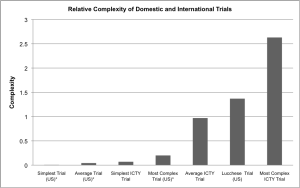

Consequently, I propose a method for measuring trial complexity based on the number of trial days, trial exhibits and trial witnesses needed to complete a trial. The figure below shows the relative complexity of trials at the ICTY and in the U.S. As you can see, the average domestic trial barely registers on the chart, and even the Lucchese trial, one of the most complex trials ever conducted in the U.S., is only about half as complex as the ICTY’s most complex trial. But measuring complexity is just the first step to understanding whether the ICTY is too slow and expensive.

Continue Reading…

January 27th, 2014 - 9:00 AM EDT |

7 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/27/guest-post-ford-complexity-efficiency-international-criminal-courts/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Your weekly selection of international law and international relations headlines from around the world:

Africa

Asia

Americas

Middle East

Europe

January 27th, 2014 - 8:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekly News Wrap: Monday, January 27, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/27/weekly-news-wrap-january-27-2014/ |

by Chris Borgen

The New York Times reports that Ilham Tohti, a Uighur economics professor, has been arrested by Chinese authorities for separatism and inciting ethnic hatred. A number of his students are also seemingly being detained. Tohti is just one person and, perhaps unfortunately for him, his case is emblematic of larger regional tensions in China and Central Asia.

The Uighurs are a Turkic-speaking ethnic group, about 80% of whom live in the southwestern part of the Xianjian Uighur Autonomous Region in Western China. Xianjiang is a geopolitical crossroads and is also important for China’s energy policy, with significant oil and natural gas reserves. Moreover, a Council on Foreign Relations backgrounder on Xianjian and the Uighurs explains that

Xinjiang shares borders with Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and the Tibet Autonomous Region, some of which have minority communities of Uighurs. Because of the Uighurs’ cultural ties to its neighbors, China has been concerned that Central Asian states may back a separatist movement in Xinjiang.

The CFR also gives a précis of the last century:

Since the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, Xinjiang has enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy. Turkic rebels in Xinjiang declared independence in October 1933 and created the Islamic Republic of East Turkistan (also known as the Republic of Uighuristan or the First East Turkistan Republic). The following year, the Republic of China reabsorbed the region. In 1944, factions within Xinjiang again declared independence, this time under the auspices of the Soviet Union, and created the Second East Turkistan Republic.

In 1949, the Chinese Communist Party took over the territory and declared it a Chinese province. In October 1955, Xinjiang became classified as an “autonomous region” of the People’s Republic of China. The Chinese government in its white paper on Xinjiang says Xinjiang had been an “inseparable part of the unitary multi-ethnic Chinese nation” since the Western Han Dynasty, which ruled from 206 BCE to 24 AD.

And then we come to the story of Ilham Tohti, the economics professor. The New York Times reports:

A vocal advocate for China’s embattled Uighur minority, Mr. Tohti, 44, was the rare public figure willing to speak to the foreign news media about the Chinese government’s policies in the vast region that borders several Central Asian countries. He was also the target of frequent harassment by the Chinese authorities, especially after he helped establish Uighurbiz.net, a website for news and commentary on Uighur issues.

There has been unrest in China’s west over the past year…

(Continue Reading)

January 26th, 2014 - 9:41 PM EDT |

Comments Off on China’s Crackdown on the Uighurs and the Case of Ilham Tohti http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/26/chinas-crackdown-uighurs/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Calls for Papers

- This serves as a reminder that the deadline for submissions for the 2014 Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law Conference is fast-approaching. The original deadline has been extended to 29 January 2014. Please also note that the keynote address will be given by Judge Kenneth Keith of the International Court of Justice. For more information, please click here (.pdf).

- Transnational Legal Theory publishes theoretical scholarship that addresses transnational dimensions of law and legal dimensions of transnational fields, regulatory regimes and evolving normative-institutional arenas. The journal is currently accepting submissions for a special symposium issue that addresses the potential and substance of Transnational Criminal Law (TCL), an evolving and still largely under-explored field of law. TCL is at the intersection of domestic, international and comparative criminal law and reaches deep into contemporary debates over conceptions of crime and illegality, social values and regulatory politics. Abstracts outlining the direction of the planned submission are invited by Monday 17 February 2014 and final papers are due by Monday 28 April 2014. Abstracts and/or submissions as well as any inquiries should be directed to tlteditorial [at] hartpub [dot] co [dot] uk or PZumbansen [at] osgoode [dot] yorku [dot] ca. For more information, click here (.doc).

Events

- ASIL has announced an event entitled: “Careers in International Organizations,” scheduled for this Wednesday, January 29, 5:30pm-7:30pm in Washington, D.C. This event will also be livestreamed. Please register/get more info here. A quick description: “Working at an international organization offers unique insight into how international law is made through the convergence of national interests, personal dynamics, global realities, and constantly evolving norms. But how does a lawyer enter these labyrinths? What is it like to work in them? How do you get the assignments that advance your career once inside? And where do you go from there? Panelists at this event sponsored by ASIL’s New Professionals Interest Group will share the perspectives they have gained from the United Nations, the World Bank, the Organization of American States, and other international organizations, answering these questions and ones posed by the audience. Panelists include: Simone Schwartz-Delgado, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; Grace Menck, Inter-American Development Bank; Heidi Jimenez, Pan-American Health Organization; and Steve Koh, ASIL (former attorney at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and International Criminal Court).”

- Students for the Promotion of International Law (SPIL), Mumbai is proud to present its flagship event to you “Reliance Industries Limited presents 5th Government Law College International Law Summit, Government Law College, Mumbai.” SPIL, Mumbai has endeavored for the past four years to promote International Law among the students and legal fraternity alike through its flagship event, the “International Law Summit”. In line with its past tradition, SPIL, Mumbai will be hosting the “5thGovernment Law College International Law Summit” with its theme “International Investment Law”, from 31st January to 2nd February, 2014.

- On February 7-8, 2014, the Brigham Young University Law School and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) will host a Workshop on Teaching International Humanitarian Law (IHL) at BYU Law School in Provo, Utah. The Workshop is targeted at law professors interested in teaching an IHL course for the first time (otherwise known as the Law of Armed Conflict), integrating IHL modules into their current courses and/or rethinking their current teaching of this important subject. Topics covered will include: Building a Course Structure; Integrating IHL into non-IHL Courses; Using Problems, Scenarios and Hot Topics in Teaching IHL; Experiential Learning in IHL Instruction; and Internships, Jobs, and Other Opportunities in IHL. The Workshop provides an opportunity for law faculty to think creatively about teaching IHL, network with others, exchange ideas, and expand teaching of these topics. The cost of the two-day seminar is $250 per person and includes breakfast and lunch both days, dinner the first day, and all workshop materials. For further information and to register, please click here.

Announcements

- Transnational Dispute Management announces another journal issue: TDM 1 (2014) – Reform of Investor-State Dispute Settlement: In Search of a Roadmap. From TDM:

“Edited by Jean E. Kalicki (Arnold & Porter LLP and Georgetown University Law Center) and Anna Joubin-Bret (Cabinet Joubin-Bret) this TDM special issue on the “Reform of Investor-State Dispute Settlement: In Search of a Roadmap” has close to 70 papers making it the largest TDM Special Issue to date. The interest in this topic, and the breadth of proposals offered by our contributors, demonstrates both the importance of holding this dialogue and the creativity of astute users and observers of the present system. This Special Issue is particularly timely in light of the European Union public consultation on investor-state dispute settlement and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership just begun by EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht.”

Last week’s events and announcements can be found here. If you would like to post an announcement on Opinio Juris, please contact us.

January 26th, 2014 - 9:30 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Events and Announcements: January 26, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/26/events-announcements-january-26-2014/ |

by Duncan Hollis

We here at Opinio Juris were saddened to hear of the passing last week of Georgetown Professor Barry Carter. Our condolences go out to his friends and family. Georgetown Dean William Treanor has a tribute to Barry here.

For my part, I’ve used Barry’s textbook (which he originally authored with Philip Trimble, then Curt Bradley, and now Allen Weiner) ever since I started teaching international law. Despite a heavy U.S. emphasis, it offers a compelling and highly accessible introduction to international law. I know it’s part of the reason so many students find themselves drawn to a career in international law. In recent months, I’d enjoyed getting to know Barry more as we both served as Advisers to the 4th Restatement on Foreign Relations Law project. I enjoyed his many comments to that effort and I know his contributions there will be sorely missed.

Readers can leave their own memories and tributes to Barry on a page at Georgetown Law’s website here.

January 25th, 2014 - 11:01 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Barry E. Carter 1942-2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/25/barry-e-carter-1942-2014/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

This week on Opinio Juris, Julian discussed the US’ funding (along with the EU and the UK) of a team of investigators gathering war crimes evidence in Syria and why that effort would probably not lead to any prosecutions. Chris pointed out a trend with regard to in cyber(in)security with his post on zero-day exploits, noting that the “money in the market has shifted from rewarding security to incentivizing insecurity.”

Duncan covered the latest breach by the US on its obligations under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations after Texas executed Edgar Tamayo, a Mexican national, earlier this week; Roger posed the question about whether the presumption against extraterritoriality only apply to the alien tort statute or also to the underlying federal common law claims in the Kiobel decision and Kevin gave us his new e-mail address as he transitions to SOAS in London.

Additionally we’ve featured stellar guest posts: one from Chantal Meloni, analyzing the latest communication to the International Criminal Court about allegations of torture carried out by UK forces against Iraqi detainees from 2004-2008; a piece from Farshad Ghodoosi continuing Duncan’s discussion on the Iranian New Deal, but offering analysis under Iranian law; and a contribution from Adam Steinman, who covered the US Supreme Court’s decision in Daimler AG v. Bauman, an Alien Tort Statute case involving human rights violations by Daimler Argentinian subsidiary during Argentina’s “dirty war” of the 1970s and 1980s.

Finally, I wrapped up the news and listed events and announcements.

Thanks again to our guest contributors and have a nice weekend!

January 25th, 2014 - 9:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekend Roundup: January 18-25, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/25/weekend-roundup-january-25-2014/ |

by Roger Alford

I just completed a draft essay on Kiobel for the Notre Dame Law Review (the symposium will include luminaries such as A.J. Bellia, Doug Cassel, William Castro, Bradford Clark, Bill Dodge, Eugene Kontorovich, Thomas Lee, Michael Ramsey, Ralph Steinhardt, Beth Stephens, and Carlos M. Vázquez). To my surprise after careful reflection there remains an important question that I have not seen discussed anywhere thus far: Does the presumption against extraterritoriality apply to the statute only or also to the underlying federal common law claims recognized in Sosa? If it only applies to the ATS, then does it follow that the underlying federal common law claims can be pursued elsewhere, such as in federal courts exercising diversity jurisdiction or in state courts exercising general jurisdiction?

To test the hypothesis, let’s assume that following Kiobel Congress immediately amended the ATS to make it clear that the statute applied extraterritorially. The amendment made no mention of the underlying common law claims one way or another. What impact would that amendment have on the extraterritorial application of the federal common law claims? If the jurisdictional statute suddenly applied extraterritorially by congressional mandate, would the underlying federal common law claims be cognizable for extraterritorial conduct and injury?

If the answer to that question is yes, then does it also follow that the only extraterritorial limitation that Kiobel recognized was with respect to the statute, not the underlying federal common law claims? Reading Kiobel in light of Sosa presents the following possible syllogism: if (1) there is a limited category of federal common law claims actionable for violations of the law of nations; and (2) the statutory canon limits the extraterritorial reach of the ATS, not the underlying common law claims; then (3) the common law claims may be pursued in federal courts exercising diversity jurisdiction or state courts exercising general jurisdiction.

The first uncontroversial premise is that the ATS does not create a cause of action for violations of the law of nations, the common law does. In Sosa the Court held that the ATS, although only a jurisdictional statute, was “enacted on the understanding that that the common law would provide a cause of action for the modest number of international law violations with a potential for personal liability….” It then held that “no development in the two centuries from the enactment of § 1350 … has categorically precluded federal courts from recognizing a claim under the law of nations as an element of common law. Congress has not in any relevant way amended § 1350 or limited civil common law power by another statute.” For such a common law claim to be actionable, however, it must be “based on the present-day law of nations” and “rest on a norm of international character accepted by the civilized world and defined with a specificity comparable to the features of the 18th-century paradigms we have recognized.” The Court in Kiobel reinforced this understanding of a “modest number” of “federal common law claims” actionable for violations of the law of nations. In other words, both Sosa and Kiobel confirm that the ATS is not the source or the limit for common law claims involving international law violations.

The second more controversial premise is that the ATS is a jurisdictional statute and that the presumption against extraterritoriality applies only to the statute, not to the underlying federal common law claims. In Kiobel the Court declared that “the presumption against extraterritoriality constrains courts exercising power under the ATS.” That presumption, the Court said, is “a canon of statutory interpretation” that assumes “when a statute has no clear indication of an extraterritorial application, it has none.” The purpose of the canon is to avoid unintended clashes between our laws and those of other nations by requiring Congress to manifest a clear intent to regulate conduct abroad. Although the ATS “does not directly regulate conduct or afford relief” the Court concluded that “we think the principles underlying the canon of interpretation similarly constrain courts considering causes of action that may be brought under the ATS.” The Court then looked to the text, history and purpose of the ATS to determine whether Congress intended for the ATS to apply abroad, and found “nothing in the statute to rebut the presumption.” Had there been such evidence, the jurisdictional statute would apply extraterritorially without altering the content or reach of the underlying common law claims. Likewise, as noted above, should Congress amend the ATS so that it applies extraterritorially, this too would not alter the content or reach of the underlying common law claims. Thus, the presumption against extraterritoriality applies to limit Congress’ grant of jurisdictional authority to adjudicate federal common law claims for violations of the law of nations.

The surprising conclusion one draws from these two premises is that federal common law claims actionable for violations of the law of nations still may be pursued in federal courts exercising foreign diversity jurisdiction or state courts exercising general jurisdiction. As for the former, foreign diversity jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332 requires a $75,000 amount in controversy and the inclusion of a U.S. citizen either as a plaintiff or defendant. The typical “foreign-cubed” facts pursued in ATS claims would be foreclosed under this grant of jurisdiction. However, where a U.S. citizen is involved in a diversity action, the federal common law claims recognized in Sosa may survive Kiobel’s presumption against extraterritoriality. The presumption against extraterritoriality will apply to the diversity jurisdiction statute as well, but as Anthony Bellia and Bradford Clark argue in their forthcoming essay “[i]t is uncontroversial that federal courts may exercise foreign diversity jurisdiction over tort claims by aliens against U.S. citizens for acts occurring outside the United States.”

This conclusion also means that state courts sitting as courts of general jurisdiction may resolve the federal common law claims recognized in Sosa. Unless one interprets the presumption against extraterritoriality articulated in Kiobel as limiting the underlying common law claims rather than the jurisdictional statute, the international law claims that heretofore were pursued in federal court under the ATS still could be pursued in state court as federal common law claims. There is nothing unusual in suggesting that federal common law claims may be adjudicated in state courts. State courts routinely apply and make federal common law, including claims involving admiralty and implicating the rights and obligations of the United States.

But let’s assume that this syllogism is wrong. If the Court’s application of the presumption against extraterritoriality applies both to the ATS and the underlying federal common law claims, there remains the possibility that state courts could fashion state common law claims based on the criteria established in Sosa. State law routinely mirrors comparable federal law. There is nothing in Sosa or Kiobel that prevents a state court from recognizing a state cause of action for violations of “a norm of international character accepted by the civilized world and defined with a specificity comparable to the features of the 18th-century paradigms,” such as piracy, violations of safe conducts, or offenses against ambassadors. Courts applying the common law already have established gradations of torts that embrace negligence, gross negligence, intentional torts and strict liability. There is no logical reason that an international law violation could not be a state common law cause of action, or at a minimum a critical factor in the determination of liability or damages under state law.

To suggest that the statutory presumption against extraterritoriality does not apply to federal common law claims (or similar state common law claims) is not to suggest the absence of territorial limits. As with the extraterritorial application of state laws, the constitutional limits of the Due Process Clause set forth in Allstate Ins. Co. v. Hague prevent state courts from applying common law claims in the absence of any “significant contact or significant aggregation of contacts, creating state interests, with the parties and the occurrence or transaction.” Nor is there any reason to think courts resolving common law claims for international law violations would go so far as to violate international limits of prescriptive jurisdiction. Both constitutional and international law impose obligations of a territorial nexus separate and apart from the statutory presumption against extraterritoriality. The territorial limits of common law claims for international law violations are derived from constitutional and international law, not canons of statutory interpretation.

I’m not convinced that all of this reasoning is correct, and even less convinced that lower courts will buy these arguments. But I thought it was important enough to flag for our readers.

January 24th, 2014 - 12:11 AM EDT |

6 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/24/presumption-extraterritoriality-apply-ats-federal-common-law-claims/ |

by Adam N. Steinman

[Adam N. Steinman is Professor of Law and Michael J. Zimmer Fellow at Seton Hall University School of Law. This contribution is cross-posted at Civil Procedure & Federal Courts Blog.]

Last week the Supreme Court issued its decision in Daimler AG v. Bauman, a case covered earlier here and here and here. In many ways, the case resembles Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, last Term’s decision on the Alien Tort Statute (ATS). The Daimler plaintiffs had brought claims under the ATS against Daimler—a German company headquartered in Stuttgart—for human rights and other violations committed by Daimler’s Argentinian subsidiary during the “dirty war” of the 1970s and 1980s. The Supreme Court’s decision in Daimler, however, is all about personal jurisdiction, and it is not limited to the ATS context.

The Ninth Circuit had held that Daimler was subject to general personal jurisdiction in California based on the activities of its American subsidiary, MBUSA. Because it involves general jurisdiction, Daimler is an important follow-up to the Court’s 2011 decision in Goodyear Dunlop v. Brown. Writing for a unanimous Court in Goodyear, Justice Ginsburg explained that general jurisdiction over corporations is proper “when their affiliations with the State are so ‘continuous and systematic’ as to render them essentially at home in the forum State.”

In Daimler, all nine Justices conclude that it would be unconstitutional for California to exercise general jurisdiction over Daimler. Justice Ginsburg again writes for the Court, although Justice Sotomayor writes a separate concurrence that disagrees with much of Justice Ginsburg’s reasoning. Parts of the decision—and some of the areas of disagreement—are harder than usual to follow because the parties either conceded or forfeited a number of potentially important points during the course of the litigation [See p.15]. That said, the most significant parts of the Daimler decision address three issues:

(1) When can a subsidiary’s activities in the forum state be attributed to the parent for purposes of general jurisdiction?

(2) More generally, when is a corporation subject to general jurisdiction under the Goodyear standard?

(3) What role (if any) do the so-called “reasonableness” factors play in the general jurisdiction context?

The majority opinion does not provide much affirmative guidance on the first question, although Justice Ginsburg rejects the Ninth Circuit’s approach. The Ninth Circuit had attributed MBUSA’s contacts to Daimler using an “agency theory,” which “rested primarily” on the premise that “MBUSA’s services were ‘important’ to Daimler, as gauged by Daimler’s hypothetical readiness to perform those services itself if MBUSA did not exist.” [p.17] Justice Ginsburg reasons that this view “stacks the deck, for it will always yield a pro-jurisdiction answer.” [p.17]. Nor—on these facts—could attribution be based on Daimler’s “control” over MBUSA. According to the Ninth Circuit, Continue Reading…

January 23rd, 2014 - 2:01 PM EDT |

Comments Off on Guest Post: Steinman–SCOTUS Decision in Daimler AG v. Bauman: Constitutional Limits on General Jurisdiction http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/23/guest-post-steinman-scotus-decision-daimler-ag-v-bauman-constitutional-limits-general-jurisdiction/ |

by Duncan Hollis

News out of Texas today that it executed Edgar Tamayo, a Mexican national, for killing a police officer, Guy Gaddis. Tamayo was one of the nationals Mexico named in the Avena case. Thus, he fell within the scope of the ICJ’s order that the United States provide ‘review and reconsideration’ of the conviction and sentence of named Mexican nationals in light of the U.S. failure to provide a right to consular access within a reasonable time of their arrest pursuant to the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR). Thus, whatever Texas’ interests in ensuring justice was served on someone who killed a police officer, the execution is a clear violation of U.S. obligations under the ICJ Statute (Art. 59), the UN Charter (Art. 94), and, of course, the VCCR itself (Art. 36), given US adherence at the time to the VCCR’s Optional Protocol.

This marks (I believe) the third Mexican national Texas has executed since the ICJ issued its decision in Avena, and since the U.S. Supreme Court declared in Medellin that the US treaty obligations in question are non-self executing, meaning that as a matter of U.S. constitutional law, the Executive is powerless to stop Texas absent further implementation of the VCCR (or other treaties) by federal legislation. The prospects of Congressional action to implement Avena, however, seem pretty dim at this point.

So, what happens now? Will Mexico continue to treat each new execution with the same weight as it has previously? There are still dozens of Mexican nationals to whom the Avena decision had purported to offer relief. I also wonder if the State Department will maintain the same level of lobbying against these executions or if its statements will become more a matter of lip service? I’d note, for example, the extent of federal lobbying seems to be lessening over time — compare Kerry’s comments on Tamayo’s case with the 2008 efforts by the White House, State, and Justice Department to delay Mr. Medellin’s execution). In other words, will the regularity with which these executions (and the arguments surrounding them) seem destined to occur diminish their visibility for either the States themselves or their nationals? Is Mexico’s claim against the United States strengthened or weakened by the United States’ continued inability (or some might say unwillingness) to comply with its international obligations? As a formal matter, one would have to insist that Mexico has more to complain about with each execution. But, on a more practical level, I’d argue Mexico’s chances for relief are likely to diminish the more the international community comes to expect continued U.S. non-compliance with the Avena judgment. That may not be the right result, but I’m thinking it’s the most likely one. What do readers think? Am I missing something?

January 23rd, 2014 - 12:44 PM EDT |

3 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/23/united-states-breaches-vienna-convention-consular-relations/ |

by Chris Borgen

All Things Considered ran an interview this past Monday with Alex Fowler, the chief privacy officer of Mozilla (developer of the Firefox web browser), stemming from a blog post Fowler had written critiquing President Obama’s speech last week concerning NSA activities. When asked about the “most glaring reform needs” that were not addressed in the President’s speech, Fowler said:

right now, we have a policy approach in Washington which is focused on not closing security holes but actually [on] hoarding information about security backdoors and holes in our public security standards and using those then to exploit them for intelligence needs. In our perspective, and I think certainly those of your listeners – as you think about the news related to Target data breaches and breaches with Snapchat and other common tools that we use every day – that what we really need is to actually focus on securing those communications platforms so that we can rely on them. And that we know that they are essentially protecting the communications that we’re engaged with.

This relates to the market for so-called “zero-day exploits,” where the U.S. government pays hackers for information about holes in software security that its intelligence and law enforcement agencies can then use for surveillance. (The market for zero-day exploits is described in greater detail in this previous post.) The U.S. also pays the sellers of these exploits to keep the holes secret, not even warning the company that has the security hole, so that the exploit may remain useful to the U.S. government for as long as possible. Unfortunately, this also means it will remain open for criminal hackers who have also discovered the hole.

The injection of U.S. government funds has transformed a formerly loose, reputation-based, market into a lucrative global bazaar with governments driving up prices and the formation of firms with business models based on finding and selling exploits to the U.S. and other governments. Although cash-rich companies like Microsoft are responding by trying to out-bid state actors for information about zero day exploits in their own products, the money in the market has shifted from rewarding security into incentivizing insecurity…

(Continue Reading)

January 23rd, 2014 - 9:51 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Hackers’ Bazaar: the President’s NSA Speech and the Market for Zero-Day Exploits http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/23/presidents-nsa-speech-market-zero-day-exploits/ |

by Julian Ku

Jess Bravin has an interesting report out in Thursday’s WSJ (subscrip. req’d) detailing U.S., UK, and EU support (and funding) for a team of investigators to gather evidence of war crimes by Syrian government and military officials.

For nearly two years, dozens of investigators funded by the U.S. and its allies have been infiltrating Syria to collect evidence of suspected war crimes, sometimes risking their lives to back up promises by Western leaders to hold the guilty accountable.

As Bravin notes, the U.S. government has issued several high profile statements warning that any war crimes committed in Syria would be punished and Syrian government officials and army commanders would be held accountable. Gathering this evidence fulfills part of this pledge to hold war criminals accountable.

What is sad about this exercise, however, is that there is little evidence that the threat of eventual criminal prosecution (issued back in 2011 by Hillary Clinton) has deterred the commission of serious atrocities by the Syrian government. The WSJ report suggest that the evidence being gathered is growing at depressingly fast rates (and this NYT report adds more horrific detail). Frankly, the threat of prosecution is either not credible, or less threatening to the Syrian army and government leaders than defeat in this increasingly desperate civil war. (Professor Jide Nzelibe and I predicted this pattern of behavior by desperate dictators long ago in this article).

Moreover, as Bravin also notes, several diplomats have suggested that amnesty for some or all of the Syrian government’s leaders would have to be considered for any successful peace deal. Since the U.S. military option to remove the current government is off the table, and since the civil war seems headed for a stalemate, it would be irresponsible of the U.S. to demand full accountability for war crimes as a condition of any peace deal. To do so might just lead to more atrocities, and still no punishment.

Which means that there is not much chance that the evidence gathered by these brave and dedicated individuals described by Bravin will ever be used in a criminal prosecution. Sure, it will be leverage during peace talks, but not much more than that.

January 22nd, 2014 - 10:39 PM EDT |

Trackbacks(1) | 5 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/22/u-s-funds-effort-gather-evidence-syrian-war-crimes-prosecutions-will-probably-never-happen/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

Posting has been a bit light lately and will continue to be light for a while, because I am in the process of relocating to London. If you would like to contact me, please use my new SOAS email address: kh33 [at] soas [dot] ac [dot] uk. I am not sure how long I will be able to get emails at my Melbourne address.

January 22nd, 2014 - 4:10 PM EDT |

Comments Off on New Email Address http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/22/new-email-address/ |

by Farshad Ghodoosi

[Farshad Ghodoosi is a JSD candidate at Yale Law School.]

In continuation of the discussion about the New Iranian Deal started by Duncan Hollis, I decided to take a stab at clarifying the Iranian side of the story. The new deal, the so-called Geneva Agreement (24 Nov. 2013) and the ensuing implementation agreement (that took effect on Jan 20th, 2014), between Iran and the 5 plus 1 group seems to be more than a joint plan of action. Practically, it attenuates some of the bites of the previous Security Council Resolutions on the Iran Nuclear Program and will create tit-for-tat commitments on both sides. Whether the agreements reached thus far create binding obligations under international law is beyond the scope of this piece and requires further details on the recent –yet unpublished – implementation agreement. However, the drafters of the agreement of Nov. 24th deftly avoided the term “agreement” and instead employed the term “comprehensive solution”.

This choice of term might have been to avoid the formalities of treaty law internationally but also domestically vis-à-vis Iran. Naming might make a difference under Iranian Law. Generally speaking, the Iranian Constitution seeds skepticism towards international agreements and contracts in the present Iranian legal system. Article 77 declares, “international protocols, treaties, contracts and agreements should be ratified by the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majlis)”. The Article is very broad and all encompassing. Those hardliners unhappy about the deal in Iran’s parliament are pressing on implementing this article, stating that the agreement needs to be ratified domestically, otherwise it is void of effects. On the other hand, supporters in parliament categorize it as a “preliminary agreement” not requiring parliament approval.

I believe a preliminary agreement is still an agreement and is subject to Article 77 of the Iranian Constitution. If I were in the shoes of the supporters of the deal in the Parliament, I would emphasize the word “comprehensive solution” as it is reflected in the text. The term “comprehensive solution” is not listed in the Article 77 of the Iranian Constitution and therefore would arguably not need parliament approval.

Another hurdle for international agreements is Article 125 of the Iranian Constitution. This Article stipulates that “signing international treaties, protocols, agreements and contracts of the Iranian states with other states and also signing conventions pertaining to international organizations, subsequent to Islamic Consultative Assembly approval, is vested in the President or his legal representative.” The Council of Guardians, the body responsible for interpreting the Constitution, restricts this Article to instances where the international instrument contains “an obligation” or “a contract” (decision March 13, 1983). It handed down its decision in a situation where “a letter of intent” for cooperation was signed between Iran and India while there were doubts whether parliament had to approve it.

Despite the language in the Iranian Constitution, I believe, it is not certain that Articles 77 and 125 make the Iranian legal system a dualist system. In dualist systems, international instruments are devoid of any status in domestic law until ratified through the legislative process. I posit that the matter should be clear in the language of the Constitution. Under Article 77, however, the sanction for non-compliance with the provision is unclear. It does not mention whether non-compliance renders the international agreements ineffectual, or makes them of lower status (similar to regulations) in relation to other domestic laws. Alternatively, it could be simply a ground for impeachment or question from the President. Article 125 also seems only to vest the signing authority on the President to render the international instruments official, and not necessarily dictate their binding nature. It might sound like a long shot, but I believe, notwithstanding the requirement of parliamentary approval, international agreements could still be invoked and enforced in Iranian domestic law—at least as a contractual agreement between parties. This interpretation makes international agreements and contracts with Iran, most of which are not ratified by parliament, valid and effective under Iranian Law.

I would like to end this post with a separate comment — the absence of any dispute resolution mechanism in the deal. It is indeed not a very smart idea to omit any form of dispute resolution mechanisms. Considering the lack of trust and the history of contention between both sides (especially Iran and the US), any minor disagreement might lead to dismantling the entire agreement and the new rapprochement (as was apparently close to happening in the implementation the Joint Action Plan). There are several potential reasons parties avoided incorporating any dispute resolution mechanism. First and foremost, they probably disliked the idea of handing over such a highly political matter to a judicial body of any sort. Another potential reason was to avoid making the agreement seem like a treaty subject to international law or otherwise a binding instrument. Nonetheless, I believe disagreements over implementing the agreement could have been vested to an arbitral body or a mediation panel at least in an advisory capacity.

January 22nd, 2014 - 11:57 AM EDT |

1 Comment » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/22/guest-post-ghodoosi-comprehensive-solution-agreement-new-iran-deal-framed-iranian-law/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Your weekly selection of international law and international relations headlines from around the world:

Africa

Asia

- North Korea has called on South Korea to end “all acts of provocation and slander,” after it warned of “an unimaginable holocaust” if the South carried out military exercises with the United States.

- Myanmar authorities have denied any civilian deaths but confirmed a clash took place after a rights group reported several people including women and a child have been killed in an attack on Rohingya Muslims in western Myanmar.

Americas

Middle East

Europe

January 20th, 2014 - 8:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekly News Wrap: Monday, January 20, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/20/weekly-news-wrap-monday-january-20-2014/ |

by Chantal Meloni

[Dr. Chantal Meloni teaches international criminal law at the University of Milan is an Alexander von Humboldt Scholar at Humboldt University of Berlin.]

1. A new complaint (technically a Communication under art. 15 of the Rome Statute) has been lodged on the 10th of January to the Intentional Criminal Court, requesting the Prosecutor to open an investigation into the denounced abuses committed by UK military forces against Iraqi detainees from 2003 to 2008.

The complaint has been presented by the British Public Interest Lawyers (PIL), representing more than 400 Iraqi victims, jointly with the Berlin-based European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR).

The lawyers’ allegation is that grave mistreatments, including torture and other degrading abuse techniques, were commonly used during the six years in which the UK and Multinational Forces operated in Iraq.

According to the victims’ account the mistreatment was so serious, widespread and spanned across all stages of detention as to amount to “systemic torture”. Out of hundreds of allegations, the lawyers focused in particular and in depth on eighty-five cases to represent the mistreatment and abuses inflicted, which would clearly amount to war crimes.

2. This is not the first time that the behaviour of the UK military forces in Iraq is challenged before the ICC. In fact, hundreds of complaints have been brought on various grounds both to domestic courts and to the ICC since the beginning of the war. As for the ICC, after the initial opening of a preliminary examination, following to over 404 communications by Iraqi victims, in 2006 the ICC Prosecutor issued a first decision determining not to open an investigation in the UK responsibilities in Iraq. According to that decision, although there was a reasonable basis to believe that crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court had been committed, namely wilful killing and inhumane treatment, the gravity threshold was not met. Indeed the number of victims that had been taken into account at that time was very limited, totalling in all less than 20 persons, so that the Prosecutor found that the ‘quantitative criteria’, a key consideration of the ICC prosecutorial strategy when assessing the gravity threshold, was not fulfilled.

Therefore, what is there new that in the view of the lawyers warranted the re-proposition of such a request? In the first place it shall be noted in this regard that during the eight years that passed since then many more abuse allegations have emerged (see the Complaint, p. 110 ff.). Most notably, hundreds of torture and mistreatment allegations show a pattern – spanning across time, technique and location – which would indicate the existence of a (criminal) policy adopted by the UK military forces when dealing with the interrogation of Iraqi detainees under their custody.

In the words of the lawyers, “it was not the result of personal misconduct on the part of a few individual soldiers, but rather, constituted widespread and systematic mistreatment perpetrated by the UK forces as a whole”. Continue Reading…

January 19th, 2014 - 9:00 AM EDT |

5 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/19/guest-post-meloni-can-icc-investigate-uk-higher-echelons-command-responsibility-torture-committed-armed-forces-iraqi-detainees/ |

by Jessica Dorsey

Calls for Papers

- The European Society of International Law’s IEL group is holding a workshop on Sept 3, 2014 in Vienna. Their Call for Papers can be found here. Please note the 1st March deadline to submit proposals.

- The Organizing Committee of the 2014 Society of Legal Scholars’ PhD Conference, to be held at the University of Nottingham on 8th of September, 2014, are inviting the submission of abstracts. This year’s theme is ‘Judging in the Twenty-First Century’. Details of the event, the call for papers and how to submit an abstract can be found here.

Events

- Cardozo School of Law, the Center for Global Communication Studies at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and the Price Media Law Moot Court Competition present an event: Snowden, Surveillance and the Pentagon Papers, on January 23, 2014 at the Cardozo School of Law in New York. More information can be found here; RSVP to cjones [at] yu [dot] edu

Announcements

Last week’s events and announcements can be found here. If you would like to post an announcement on Opinio Juris, please contact us.

January 19th, 2014 - 8:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Events and Announcements: January 19, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/19/events-announcements-january-19-2014/ |

by An Hertogen

In the past fortnight on Opinio Juris, Kevin wasn’t convinced by the Muslim Brotherhood’s argument that can accept the ICC’s jurisdiction on an ad hoc basis because it is still Egypt’s legitimate government. He also discussed the OTP’s motion to challenge Rule 134quater and the Trial Chamber’s decision to conditionally excuse Ruto from continuously attending his trial in The Hague.

Julian gave the US State Department an “F” over its handling of the visa fraud allegations against India’s Deputy Consul-General in New York. Julian was also doubtful about a recommendation for the US to accede to UNCLOS as a way to assert leadership and push back China’s claims in the East and South China Seas.

In two guest posts, Lorenzo Kamel compared the EU’s approach to Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian Territories with its approach to Northern Cyprus and Western Sahara. Further on Israel and Palestine, Eliav Lieblich discussed a recent court hearing in which Israel is trying to revive maritime prize law against a Finnish ship intercepted when it tried to breach the Gaza blockade.

We engaged in cross-blog dialogues with Kevin’s thoughts on Manuel Ventura’s critique of specific direction over at Spreading the Jam, and a discussion with EJIL:Talk! of the European Court of Human Rights’ decision in Jones v. UK, discussed on our end by Bill Dodge and Chimène Keitner.

In other posts, Duncan asked whether the interim agreement over Iran’s nuclear program was a secret treaty, Kristen shared reflections on UN law making, Deborah discussed the inaccuracy of attaching the “al-Qaeda” label too liberally and the political consequences of attaching such a label, and Peter pointed out a key provision on Obama’s NSA reforms (policy directive) allowing foreigners as well as Americans data protection with regard to bulk surveillance data.

If you want more to read, you can check out the AJIL Agora on Kiobel, mentioned by Julian, or read the new blog Global Military Justice Reform to which Deborah drew our attention.

Finally, I wrapped up the news (1, 2) and listed events and announcements (1, 2).

Have a nice weekend!

January 18th, 2014 - 6:00 AM EDT |

Comments Off on Weekend Roundup: January 4-17, 2014 http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/18/weekend-roundup-january-4-17-2014/ |

by Peter Spiro

From the third paragraph of President Obama’s implementation of surveillance reforms (Presidential Policy Directive/PPD-28).

[O]ur signals intelligence activities must take into account that all persons should be treated with dignity and respect, regardless of their nationality or wherever they might reside, and that all persons have legitimate privacy interests in the handling of their personal information.

The primary operative provision of the directive, section 2, adopts limitations on bulk surveillance data that “are intended to protect the privacy and civil liberties of all persons, whatever their nationality and regardless of where they might reside.” Likewise for section 4 and the safeguarding of personal information. (Protections for non-citizens are much more prominent in the operative instrument than in Obama’s Justice Department speech today, which unsurprisingly played to domestic politics more than international sensitivities, though it is there, too.)

So Obama bought into a key Review Group recommendation. Whether or not one thinks the overall policy will suffice to rein in the NSA (a mixed verdict, at best), the fact that it applies to citizens and non-citizens alike strikes me as a pretty big deal – can’t think of an obvious precedent. As the biggest player on the global landscape, it will certainly contribute to the crystallization of an international right to privacy.

It also reduces the importance of the Supreme Court’s 1990 ruling in Verdugo-Urquidez, which found non-US citizens outside the United States to enjoy no Fourth Amendment rights (and which no doubt supplied the key legal authority for NSA programs aimed at foreigners). That doctrine becomes less consequential as the net supplied by other sources of law rises below rights located in the Constitution. The absence of constitutional rights no longer translates into no rights. This is another front on which sovereigntist victories in the Supreme Court will be hollowed out over the long run by forces beyond its control.

January 17th, 2014 - 12:12 PM EDT |

5 Comments » http://opiniojuris.org/2014/01/17/obamas-nsa-speech-foreigners-get-protections/ |

by Kevin Jon Heller

The decision was given orally, and no written decision is available yet. But here is what The Standard‘s online platform is reporting:

The International Criminal Court has conditionally excused Deputy President William Ruto from continuos presence at trial but with some conditions.

The judges outlined nine conditions during the Wednesday ruling. ICC Presiding Judge Eboe-Osuji in the oral ruling said: “The Chamber hereby conditionally excuses Mr Ruto from continuous presence at trial on the following conditions: As indicated in the new rule 134, a waiver must be filed. That’s one condition. The further conditions are these: in the case, two, when victims present their views and concerns in person, three, the entirety of the delivery of the judgement in the case, four, the entirety of the sentencing hearing, if applicable, five, the entirety of the sentencing, if applicable, six, the entirety of the victim impact hearings, if applicable, seven, the entirety of the reparation hearings, if applicable, seven, the first five days of hearing starting after a judicial recess as set out in regulation 19 B I S of the regulations of the Court, and nine, any other attendance directed by the Chamber either/or other request of a party or participant as decided by the Chamber. The Chamber considers that the attendance of Mr Ruto pursuant to the requirement indicated in condition number eight, being attendance and first five days of hearing starting after a judicial recess, will require him to be present for today’s hearing and the next — sorry — starting tomorrow and the next five days. However, in view of the need for Mr Ruto to deputise for the president of the Republic of Kenya during his absence from the country from the 16 of January 2014, Mr Ruto is excused from presence at trial on the 16th and the 17th of January 2014. Mr Ruto shall, however, be present for the remainder of the period indicated under condition number eight”.

Kenya shouldn’t get too excited about the Trial Chamber’s ruling. Remember: the Appeals Chamber reversed the Trial Chamber’s previous decision concerning Ruto’s presence and articulated a very different, and much narrower, interpretation of Art. 63(1) of the Rome Statute. The OTP was never going to win at the trial level; the Appeals Chamber is much more likely to take seriously the differences between Rule 134quater and the multi-part test it previously articulated and to consider whether the Rule is ultra vires.

We shall see.