[John Tasioulas is Yeoh Professor of Politics, Philosophy and Law at the Dickson Poon School of Law, King’s College London and Visiting Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School. This is the third post in the Defining the Rule of Law Symposium, based on this article (free access for six months). The first is here and the second, here.]

One can, without linguistic impropriety, use the phrase “the rule of law” to denote a number of significant though distinct ideas. Most expansively of all, it can be used to refer to the rule of good law: to all of the values, running the gamut from justice through charity to efficiency, that law should embody or promote. This value catalogue, although probably very long and diverse, would not lack utility, since not everything we value need fall within the legitimate ambit of legal concern.

Still, those who have seriously meditated on the rule of law usually had something more specific in mind than the rule of good law. They have typically sought to articulate the ideal of the rule of law in a way that satisfies two constraints. First, a constraint of pluralism: the rule of law is only one evaluative standard, among various others, for assessing laws and legal institutions. Second, a constraint of unity or coherence: the various demands of the rule of law must be the expression of a coherent underlying ethical concern. Given the pluralism constraint, that underlying concern cannot merely consist in the ultra-minimal one of relevance to the ethical assessment of law.

Notoriously, there are ‘thicker’ and ‘thinner’ articulations of the rule of law, the former often called ‘substantive’, the latter ‘formal/procedural’, but they all typically seek to satisfy the desiderata of pluralism and coherence.

Ronald Dworkin, a leading proponent of the thick view, characterizes the rule of law as ‘rule by an accurate public conception of individual [moral] rights’ (R Dworkin, A Matter of Principle (Harvard University Press, 1985), 11-12). Since not all of the values relevant to the assessment of law are rights-based considerations, the pluralist constraint is satisfied. Meanwhile, coherence is secured through the organizing idea of moral rights that are appropriately reflected in law. Yet Dworkin’s view seems too expansive insofar as it equates the rule of law with justice generally, at least to the extent that the latter bears on law. This is because a venerable tradition of thought – one that includes Grotius, Hume, Kant and Mill – construes the concept of justice as picking out just those moral duties that have associated rights.

Hence, the motivation to adopt a ‘thin’ account of the rule of law, one centring on a series of formal and procedural requirements, e.g. that laws be prospective, framed in general and accessible terms, not constantly changing, and applied consistently by officials (see the classic recent formulation in J. Raz, ‘The Rule of Law and its Virtue’, Law Quarterly Review 93 (1977): 195-211). The limited scope of the rule of law, thinly understood, means that a legal system can in principle satisfy it in spite of being deficient with respect to values such as human rights or democracy. But the up-side is that the desideratum of pluralism is secured. On the other hand, the coherence of the thin view consists in the fact that its formal and procedural requirements pay proper tribute to the autonomy and dignity of those subject to the law, enabling them to make important choices against the background of being able reliably to predict how the law is liable to impinge on their lives in various scenarios. Like many with ‘thick’ sympathies, McCorquodale finds the thin view all-too minimalist, dismissing it as giving an account not of ‘the rule of law’, but of ‘rule by law’.

McCorquodale’s article offers a rival conception of the rule of law, which he then proceeds to show is applicable to international law. I focus here only on the first stage of his argument. For McCorquodale, the rule of law incorporates four elements conceived as objectives: “to uphold legal order and stability, to provide equality of application of the law, to enable access to justice for human rights, and to settle disputes before an independent legal body” (p.8) We may interpret this account as seeking to fuse the merits of the thick and thin accounts, while jettisoning the limitations of each, by plotting an intermediate position between them. For, arguably, three of its elements would be endorsed by most adherents of the thin view, so that it is the addition of access to justice for human rights that constitutes the distinctive ‘value added’ of his account relative to the former view. Since, presumably, not all moral rights are also human rights, this distinguishes his position from the even thicker Dworkinian version, thus avoiding the objection that he equates the rule of law with justice insofar as it bears on law.

The first question about McCorquodale’s account centres on what he means by human rights. A close reading of his article suggests he has in mind those rights laid down in international human rights law. But how can the content of an ethical value or norm, such as the rule of law, be dependent on a contingent and fallible human creation, such as international human rights law? Isn’t human rights law properly seen as responsible to a background morality of human rights to which it gives inevitably imperfect expression? This is why Dworkin speaks of an ‘accurate public conception’ of moral rights. Moreover, even if we were persuaded by McCorquodale’s assurances that the relevant human rights legally bind all states, and even non-state actors such as corporations, the fact remains that they might not have been binding or could cease to be so in the future. Would the demands of the rule of law fluctuate in line with these changes?

Let’s assume that McCorquodale either revises his view so as to appeal to human rights of morality, rather than law, or else has that he has some compelling defence of his reliance on legal norms. The question then arises: why add human rights, in particular, to the familiar formalist constraints? After all, there are many values that the law should advance, other than human rights, such as peace, the preservation of nature, humanitarian concern, economic efficiency, and so on. Is it not simply arbitrary to conjoin human rights, from all these other legally-relevant values, to the formalist requirements? In other words, in trying to take a stand between thick and the thin, McCorquodale appears to fall foul of the desideratum of unity or coherence.

The likely response is that he is not incorporating all human rights into the rule of law, but only some of them. On the one hand, he claims that the rule of law requires access to justice for all human rights (p.18). On the other hand, he asserts that not all human rights are therefore part of the rule of law, instead only some are (p.7). Presumably, the included human rights will be that sub-set that suitably coheres with the three formalist requirements. The human rights that are ‘within the rule of law’, McCorquodale says, include ‘the right to a fair trial, the right to liberty, the right to equality and the right not to be discriminated against’. Their inclusion is on the basis that they are ‘procedural rights directly relevant to the rule of law’. (p.17).

But this move confronts two hefty challenges. The first is that it remains unclear what the principle of selection is for determining which human rights form part of the rule of law. McCorquodale’s answer seems to be that these are procedural rights, but the sense given to ‘procedural’ is fuzzy and overly expansive. It is not at all obvious in what sense the rights to liberty and non-discrimination, which figure in his list of incorporated rights, are procedural rights in a way that, for example, the rights to life or to political participation are not. Absent an adequate explanation, his account of the rule of law lacks coherence, even if we grant the somewhat nebulous thesis that while the rule of law enjoins the protection of all human rights not all such rights are part of the rule of law.

The second challenge is that, even with a convincing principle of selection, we might discover that his view ultimately collapses into a version of the thin view. This is because the latter view can be made to encompass some human rights, i.e. those that integrate with its concern to safeguard human autonomy and dignity by means of the predictability achieved through compliance with the familiar set of formal and procedural demands. The thin view of the rule of law, for example, incorporates a strong prohibition on retrospective criminal punishment, which itself reflects a corresponding human right. It also incorporates a demand of formal equality in the application of law – treating like cases alike – that also plausibly implicates a human right. So, the thin view seems compatible with a more limited, yet also more coherent, embrace of human rights within the rule of law ideal. If McCorquodale seeks a more generous embrace of human rights within the rule of law ideal, without going to the extreme of incorporating all of them, he needs to be explain how this can be achieved without sacrificing the overall coherence of the ideal, turning it into an ad hoc, but incomplete, list of legally-relevant values.

Print This Page

Print This Page O’Keefe’s book will be of primary interest to scholars, because it is very long and extremely dense. But it’s a must-read, both for its comprehensiveness and for its impressive willingness to tackle fundamental theoretical issues in ICL, such as the nature of an international crime. The only downside to the book is its expense — £95. I hope OUP will release a paperback version in the near future.

O’Keefe’s book will be of primary interest to scholars, because it is very long and extremely dense. But it’s a must-read, both for its comprehensiveness and for its impressive willingness to tackle fundamental theoretical issues in ICL, such as the nature of an international crime. The only downside to the book is its expense — £95. I hope OUP will release a paperback version in the near future.

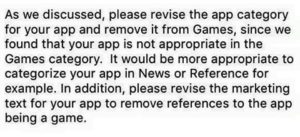

The game in question — from which the screenshot is taken — is entitled

The game in question — from which the screenshot is taken — is entitled  The gaming community is mocking Apple’s decision, and rightfully so. As Hardcore Gamer points out, “Liyla and the Shadow of War is a game. Having a serious message about a real-world conflict doesn’t make it any less so, and it’s insulting not just to the developers but to gaming in general to say otherwise.” Indeed, there is no way Apple actually believes that Liyla and the Shadow of War isn’t a game; it simply doesn’t want to host a game developed by a Palestinian that encourages thinking critically about Israel’s violence toward Palestinians. But rejecting the game on political grounds would itself be seen as political — correctly — so Apple comes up with a ridiculous pretext for rejecting it and hopes nobody notices.

The gaming community is mocking Apple’s decision, and rightfully so. As Hardcore Gamer points out, “Liyla and the Shadow of War is a game. Having a serious message about a real-world conflict doesn’t make it any less so, and it’s insulting not just to the developers but to gaming in general to say otherwise.” Indeed, there is no way Apple actually believes that Liyla and the Shadow of War isn’t a game; it simply doesn’t want to host a game developed by a Palestinian that encourages thinking critically about Israel’s violence toward Palestinians. But rejecting the game on political grounds would itself be seen as political — correctly — so Apple comes up with a ridiculous pretext for rejecting it and hopes nobody notices.