Not the kind of fairy tale you were thinking of.

Not normally my thing, but I saw a link for of the late Princess of Wales on the 20th anniversary of her death – and from The Guardian, no less – and so I clicked. It’s a long piece, but as I read, the writing was so good I began to weep with envy (figuratively speaking). I kept wondering: “Who is the remarkable author of this piece?”

Well, it’s Hilary Mantel. I’m embarrassed to say I’m the only person in the Western World who has not read Wolf Hall, but if this gives any indication – someone please send me a battered paperback, priority mail:

By her own account, Diana was not clever. Nor was she especially good, in the sense of having a dependable inclination to virtue; she was quixotically loving, not steadily charitable: mutable, not dependable: given to infatuation, prey to impulse. This is not a criticism. Myth does not reject any material. It only asks for a heart of wax. Then it works subtly to shape its subject, mould her to be fit for fate. When people described Diana as a “fairytale princess”, were they thinking of the cleaned-up versions? Fairytales are not about gauzy frocks and ego gratification. They are about child murder, cannibalism, starvation, deformity, desperate human creatures cast into the form of beasts, or chained by spells, or immured alive in thorns. The caged child is milk-fed, finger felt for plumpness by the witch, and if there is a happy-ever-after, it is usually written on someone’s skin.

Mantel shares my own thoughts about grief and mourning, which, in our own superficial culture, is certainly worth a rethink:

A deathbed, once, was a location dense with meaning, a room packed with the invisible presences of angels, devils, ancestors. But now, as many of us don’t believe in an afterlife, we envisage no final justice, no ultimate meaning, and have no support for our sense of loss when “positivity” falters. Perhaps we are baffled by the process of extinction. In recent years, death narratives have attained a popularity they have not held for centuries. Those with a terminal illness scope it out in blogs. This summer the last days of baby Charlie Gard riveted worldwide attention. But what is the point of all this introspection? Even before the funeral, survivors are supposed to flip back to normal. “Keeping busy” is the secret, Prince William has advised.

Brava, madam

Grief is exhausting, as we all know. The bereaved are muddled and tense, they need allowances made. But who knows you are mourning, if there is nothing but a long face to set you apart? No one wants to go back to the elaborate conventions of the Victorians, but they had the merit of tagging the bereaved, marking them out for tenderness. And if your secret was that you felt no sorrow, your clothes did the right thing on your behalf. Now funeral notices specify “colourful clothing”. The grief-stricken are described as “depressed”, as if sorrow were a pathology. We pour every effort into cheering ourselves up and releasing balloons. When someone dies, “he wouldn’t have wanted to see long faces”, we assure ourselves – but we cross our fingers as we say it. What if he did? What if the dead person hoped for us to rend our garments and wail?

When Diana died, a crack appeared in a vial of grief, and released a salt ocean. A nation took to the boats. Vast crowds gathered to pool their dismay and sense of shock. As Diana was a collective creation, she was also a collective possession. The mass-mourning offended the taste police. It was gaudy, it was kitsch – the rotting flowers in their shrouds, the padded hearts of crimson plastic, the teddy bears and dolls and broken-backed verses. But all these testified to the struggle for self-expression of individuals who were spiritually and imaginatively deprived, who released their own suppressed sorrow in grieving for a woman they did not know. The term “mass hysteria” was a facile denigration of a phenomenon that eluded the commentators and their framework of analysis. They did not see the active work the crowds were doing. Mourning is work. It is not simply being sad. It is naming your pain. It is witnessing the sorrow of others, drawing out the shape of loss. It is natural and necessary and there is no healing without it.

Read the whole thing here.

Postscript on August 28, from the poet Melissa Green: Cynthia, I find most historical fiction what I call ‘Nike’ dressed up in Nikes – it isn’t real, it’s a costume drama with people speaking some sort of BBC British. But reading WOLF HALL (Yes, I too, came late to the party) I was quite astonished. I could see Cromwell standing in the garden with his cronies, and something about her language made me see utterly the sun on one cheek that shone differently on the cheek on another. The air sounded different, the footfalls, the wheeled carts, the snapping flags over Windsor, without even mentioning them. I believed I was there the way you do in the best movies–you blink when it’s all over and are stunned to find yourself in the 21st century. I was captivated as a reader, but as a writer, I kept flipping back and forth to find out how she did it, how the light looked utterly odd, the weight of their bodies on the paving stones sounded unusual. I couldn’t find out how she did it. And she did it better in the first book than in the second. I think she’s onto something here with Diana, and has written in a complex way about her. xo

Postscript on August 28, from the poet Melissa Green: Cynthia, I find most historical fiction what I call ‘Nike’ dressed up in Nikes – it isn’t real, it’s a costume drama with people speaking some sort of BBC British. But reading WOLF HALL (Yes, I too, came late to the party) I was quite astonished. I could see Cromwell standing in the garden with his cronies, and something about her language made me see utterly the sun on one cheek that shone differently on the cheek on another. The air sounded different, the footfalls, the wheeled carts, the snapping flags over Windsor, without even mentioning them. I believed I was there the way you do in the best movies–you blink when it’s all over and are stunned to find yourself in the 21st century. I was captivated as a reader, but as a writer, I kept flipping back and forth to find out how she did it, how the light looked utterly odd, the weight of their bodies on the paving stones sounded unusual. I couldn’t find out how she did it. And she did it better in the first book than in the second. I think she’s onto something here with Diana, and has written in a complex way about her. xo

Postscript on August 27: On Facebook, Daniel Porter contributed G.K. Chesterton‘s remarks on fairy tales to the post: “Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear.” – Tremendous Trifles (1909), XVII: “The Red Angel”

Postscript on August 27: On Facebook, Daniel Porter contributed G.K. Chesterton‘s remarks on fairy tales to the post: “Fairy tales, then, are not responsible for producing in children fear, or any of the shapes of fear; fairy tales do not give the child the idea of the evil or the ugly; that is in the child already, because it is in the world already. Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey. What fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey. The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination. What the fairy tale provides for him is a St. George to kill the dragon. Exactly what the fairy tale does is this: it accustoms him for a series of clear pictures to the idea that these limitless terrors had a limit, that these shapeless enemies have enemies in the knights of God, that there is something in the universe more mystical than darkness, and stronger than strong fear.” – Tremendous Trifles (1909), XVII: “The Red Angel”

A few years ago, I drove from Paris to Provence in a little silver Citroën to explore Avignon, the birthplace of a French theorist is the subject of my forthcoming book, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (spring 2018 with Michigan State University Press). One facet of Avignon I didn’t experience, however, was the Quatuor Girard, an eminent string quartet formed by members of the Girard family, René’s great-nieces and great-nephews. My interest was not entirely research, however, but largely aesthetics. Listen to the short recording below.

A few years ago, I drove from Paris to Provence in a little silver Citroën to explore Avignon, the birthplace of a French theorist is the subject of my forthcoming book, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (spring 2018 with Michigan State University Press). One facet of Avignon I didn’t experience, however, was the Quatuor Girard, an eminent string quartet formed by members of the Girard family, René’s great-nieces and great-nephews. My interest was not entirely research, however, but largely aesthetics. Listen to the short recording below.

You thought British spy George Smiley was gone for good? He’s back in

You thought British spy George Smiley was gone for good? He’s back in

Instead, in the autumn of 1932, the Soviet politburo, the elite leadership of the Communist Party, decided to use the famine to crush Ukraine’s sovereignty and block any future peasant rebellion. They took a series of decisions that deepened the famine in the Ukrainian countryside, blacklisting villages and blocking escape. At the height of the crisis, organised teams of policemen and local party activists, motivated by hunger, fear and a decade of hateful propaganda, entered peasant households and took everything edible: potatoes, beets, squash, beans, peas, farm animals and even pets. Immediately afterwards, they banned anyone from leaving Ukraine and set up cordons around the cities so that peasants could not get help.

Instead, in the autumn of 1932, the Soviet politburo, the elite leadership of the Communist Party, decided to use the famine to crush Ukraine’s sovereignty and block any future peasant rebellion. They took a series of decisions that deepened the famine in the Ukrainian countryside, blacklisting villages and blocking escape. At the height of the crisis, organised teams of policemen and local party activists, motivated by hunger, fear and a decade of hateful propaganda, entered peasant households and took everything edible: potatoes, beets, squash, beans, peas, farm animals and even pets. Immediately afterwards, they banned anyone from leaving Ukraine and set up cordons around the cities so that peasants could not get help.

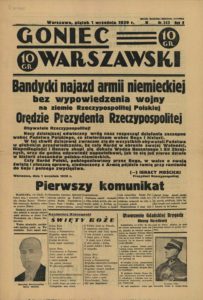

September 1, 1939, is the day Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

September 1, 1939, is the day Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Marat Grinberg writes about

Marat Grinberg writes about

Postscript on August 28, from the poet

Postscript on August 28, from the poet  Postscript on August 27: On Facebook, Daniel Porter contributed

Postscript on August 27: On Facebook, Daniel Porter contributed