But wait! It gets better! More on Huck Finn and the n-word.

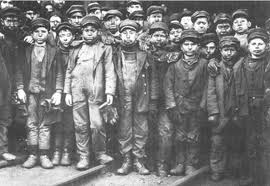

Friday, December 31st, 2010Yesterday, I wrote about the latest flap over Mark Twain‘s use of the n-word in Huckleberry Finn. NYC Councilman Charles Barron apparently thinks the book should be banned: “I find it interesting that Huckleberry Finn is a classic when it says [the n-word] 200 times,” he said.

Barron is not alone in his reservations. Poet and professor Sam Gwynn made this comment on yesterday’s post:

“Frankly, I just can’t teach it any longer. I know it’s great, and I can lecture for a day or so about how Twain is being faithful to the dialects and to the way that people spoke back then. But trying to lecture about its literary merits takes a back seat when I see how African American students (I’m talking about teenage sophomores, taking the class for core credit) are reacting to the iterations of THAT WORD. The problem is that Twain doesn’t distinguish between those who are using the word in a “kindly” manner (we could probably assume that this is the only word for black people that Huck has ever heard) and those who are using it an an epithet. Used indiscriminately in these ways, it just makes everyone in a classroom uncomfortable. Maybe if I were a better (or younger) teacher I could use this book to challenge all kinds of assumptions about language and art. I just don’t find myself up to the fight anymore, at least at the sophomore level. I think this is a pretty good 2/3 of a novel, but I really wonder why it has become canonized as the GAN.” [That’s the Great American Novel for the uninitiated.]

Now, here’s the news flash: A constant reader tipped me off that Barron’s problem is about to be solved by NewSouth books! Dr. Alan Gribben is publishing a new edition that, among other innovations, dispenses with the n-word altogether.

Gribben explains that Twain’s novels “can be enjoyed deeply and authentically without those continual encounters with hundreds of now-indefensible racial slurs.” It is the first volume to wash out Twain’s mouth with soap. Gribben believes that the presence of the n-word has gradually diminished the readership of Twain’s masterpiece.

Gribben said that another radical departure from standard editions is that these will be published as the continuous narrative that he says the author originally envisioned. “People during that time did not think of him as a fiction writer,” the Twain scholar told The Montgomery Advertiser. “Twain had difficulty at times developing plot lines for his novels and much preferred his travel books.”

But dumping the n-word is clearly the controversy that will boost sales.

I think he’s on to something. As a woman, I have always had issues about the ending of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. You know, the bit where Kate kneels down and blathers on about being her husband’s slave. Surely one of our modern-day blank verse wizards could crank out something a little less offensive? For that matter, I would like to see the b-word, the c-word, and the w-word eliminated from our public discourse about females running for office.

And there’s way, way too much violence in the Bible. Lots of foreskins gathered, a number of rapes (including one gang rape), massacres on a regular basis. Think of all those psalms that begin with rivers or vineyards and end with a wish that someone’s brains be dashed out against a wall. These nasty bits could do with a serious editing and revision … whoops! Stephen Mitchell already has.

Seriously, though. Sam Gwynn’s objections to the book are not to be taken lightly — Sam is a smart guy. But the Bowdlerization of Twain concerns me.

The new Twain will be out in February. Can we wait?

Postscript on 1/4: NewSouth books replies in the comments section below:

Cynthia and Sam, thank you both for your thought-provoking comments about this. The best thing NewSouth’s edition of Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn could do is generate more discussion about race, language, and literature, and we were pleased to read your post.

Again, we’ll note that the inspiration for this volume of Twain’s books came from Dr. Gribben’s actual conversations with teachers, uncomfortable with or in some cases restricted from teaching especially Huckleberry Finn because of the language within. We see our edition as a teaching tool with numerous applications, from the teacher who wants to teach Twain’s works without getting into the language controversy, to a teacher who wants to teach the NewSouth edition side-by-side with another edition to specifically discuss controversial language and responses to the two works. Before this edition, that wouldn’t have been possible.

The publisher promises to post the introduction to the book on its website soon.

Postscript on 1/5: Hey, we started a fire with this one! First the Book Haven, then the world: check it out here.