“Pity the Beautiful”: The necessary angel and the sound of light

Sunday, April 29th, 2012 A postcard in the mail, telling me Dana Gioia‘s new book, Pity the Beautiful, is officially out. It’s the first collection since he stepped down as chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts in 2009. The postcard, with an amiable handwritten note from Mary Gioia, invited me to a reading and discussion at Kepler’s in Menlo Park on Wednesday, May 2, at 7 p.m. (Another one, on May 15, will take place at the Booksmith, 1644 Haight Street, San Francisco.)

A postcard in the mail, telling me Dana Gioia‘s new book, Pity the Beautiful, is officially out. It’s the first collection since he stepped down as chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts in 2009. The postcard, with an amiable handwritten note from Mary Gioia, invited me to a reading and discussion at Kepler’s in Menlo Park on Wednesday, May 2, at 7 p.m. (Another one, on May 15, will take place at the Booksmith, 1644 Haight Street, San Francisco.)

I already wrote about Dana’s ghost story here, and a little about the book itself here, and about the magical evening in Santa Rosa, when Dana read some of the poems to me and his wife Mary here.

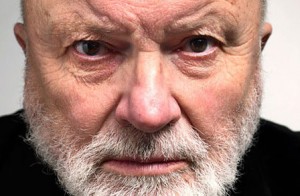

I was intrigued that the new book is dedicated to Morten Lauridsen, with the words “the necessary angel” beneath the composer’s name. Some years ago Dana sent me Lauridsen’s Lux Aeterna – a marvel. I’d never heard of the composer before Dana’s introduction – he’s largely overlooked in the MSM, though widely performed in choral music circles.

The composer said in an interview with Bruce Duffie:

I’m getting all this mail on the Lux Aeterna, because it’s a large cycle; every one of the five movements relates to light, a universal symbol in so many ways. It was a great deal of pleasure to write that particular cycle, and I wrote it as my mother was in the process of dying, so it was a way of, as so many artists do, of dealing with that kind of a situation in an artistic way. … On Lux Aeterna and so many of my works, I like the immediacy — to draw my listener in immediately, to hold their attention, to transport them, to do something to do them on some level, whether it’s excite them, or move them, or elate them, or whatever.

The connection is no surprise, really. Dana began his studies at Stanford with aspirations to become a composer. Since changing directions towards poetry and business (he has an M.B.A.), he has created the libretti for two operas – Alva Henderson‘s Nosferatu, and Paul Salerni‘s Tony Caruso’s Last Broadcast. Fewer know Dana was one of the champions of Derrière Guard, founded by the composer Stefania de Kenessey.

Lauridsen got a National Medal of Arts in 2007 – during Dana’s term as chairman of the NEA. Then Dana stepped down and became the Judge Widney Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at the University of Southern California – where Lauridsen has been a professor of composition at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music for more than three decades.

So Dana has at last returned to poetry full time. The new collection has many fine poems, and a few translations. The title poem is likely to get the most notice, but I know the one I’ll remember is the three-part “Special Treatments Ward”:

I.

So this is where the children come to die,

hidden on the hospital’s highest floor.

They wear their bandages like uniforms

and pull their IV rigs along the hall

with slow and careful steps. Or bald and pale,

they lie in bright pajamas on their beds,

watching another world on a screen.

The mothers spend their nights inside the ward,

sleeping on chairs that fold out into beds,

too small to lie in comfort. Soon they slip

beside their children, as if they might mesh

those small bruised bodies back into their flesh.

Instinctively they feel that love so strong

protects a child. Each morning proves them wrong.

No one chooses to be here. We play the parts

that we are given – horrible as they are.

We try to play them well, whatever that means.

We need to talk though talking breaks our hearts.

The doctors come and go like oracles,

their manner cool, omniscient, and oblique.

There is a word that no one ever speaks.

II.

I put this poem aside twelve years ago

because I could not bear remembering

the faces it evoked, and every line

seemed – still seems – so inadequate and grim.

What right had I whose son had walked away

to speak for those who died? And I’ll admit

I wanted to forget. I’d lost one child

and couldn’t bear to watch another die.

Not just the silent boy who shared our room,

but even the bird-thin figures dimly glimpsed

shuffling deliberately, disjointedly

like ancient soldiers after a parade.

Whatever strength the task required I lacked.

No well-stitched words could suture shut these wounds.

And so I stopped …

But there are poems we do not choose to write.

III.

The children visit me, not just in dream,

appearing suddenly, silently –

insistent, unprovoked, unwelcome.

They’ve taken off their milky bandages

to show the raw, red lesions they still bear.

Risen they are healed but not made whole.

A few I recognize, untouched by years.

I cannot name them – their faces pale and gray

like ashes fallen from a distant fire.

What use am I to them, almost a stranger?

I cannot wake them from their satin beds.

Why do they seek me? They never speak.

And vagrant sorrow cannot bless the dead.

(Meet you at the reading on Wednesday at Kepler’s. And if you’re too far away, check out these 2011 interviews with Dana and Martin Perlich here. Below, Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium – he says “it’s become the best-selling octavo in the history of Theodore Presser, who has been in business for over two hundred years now. We’ve had perhaps 3,000 performances of it.”)