Nine ways to end lies. From Solzhenitsyn with love.

Saturday, July 30th, 2016

Nyet.

A few days ago we wrote about lies and totalitarianism. Then I revisited Nobel writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn‘s essay on the subject in The Washington Post. It was dated February 12, 1974, the day he was arrested and deported. It was published nearly a week later on February 18. The article a useful reminder that sometimes the Soviet society had a lot in common with our own – perhaps because both are predicated on human nature, which is pretty much the same anywhere.

“At one time we dared not even to whisper. Now we write and read samizdat, and sometimes when we gather in the smoking room at the Science Institute we complain frankly to one another: What kind of tricks are they playing on us, and where are they dragging us? Gratuitous boasting of cosmic achievements while there is poverty and destruction at home. Propping up remote, uncivilized regimes. Fanning up civil war. And we recklessly fostered Mao Tse-tung at our expense – and it will be we who are sent to war against him, and will have to go. Is there any way out? And they put on trial anybody they want, and they put sane people in asylums – always they, and we are powerless.”

Well, we’ve fanned wars, too. And propped up remote regimes. And we’ve sponsored monsters and then turned against them. This election year has convinced me that lies are a bi-partisan, non-partisan, international issue, throughout all ages.

Solzhenitsyn declared war – the only war within his power: the personal non-participation in lies. “This opens a breach in the imaginary encirclement caused by our inaction. It is the easiest thing to do for us, but the most devastating for the lies,” he wrote. “Because when people renounce lies it simply cuts short their existence. Like an infection, they can exist only in a living organism.”

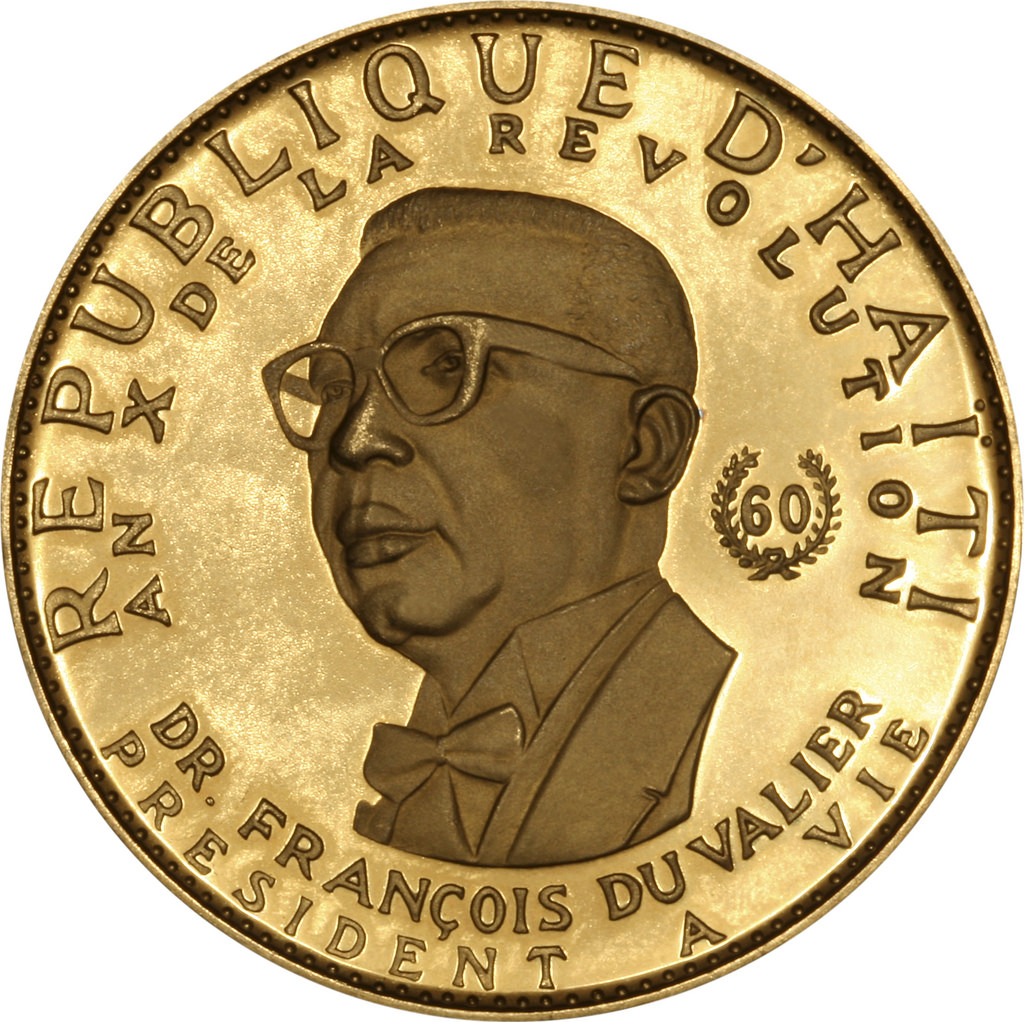

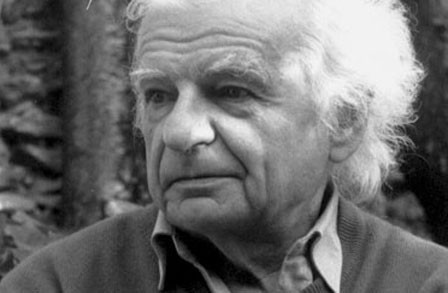

Solzhenitsyn in Cologne, 1974

It will be dangerous. “For young people who want to live with truth, this will, in the beginning, complicate their young lives very much, because the required recitations are stuffed with lies, and it is necessary to make a choice. But there are no loopholes for anybody who wants to be honest: On any given day any one of us will be confronted with at least one of the above-mentioned choices [actually, below-mentioned here – ED] even in the most secure of the technical sciences.”

“Either truth or falsehood: Toward spiritual independence, or toward spiritual servitude.”

You say it is still not easy? It is easier than self-immolation or a hunger strike, he writes. “And he who is not sufficiently courageous even to defend his soul – don’t let him be proud of his ‘progressive’ views, and don’t let him boast that he is an academician or a people’s artist, a merited figure, or a general – let him say to himself: I am in the herd, and a coward. It’s all the same to me as long as I’m fed and warm.”

His 9-point pledge, that he invites everyone to join, wherein you:

- Will not henceforth write, sign, or print in any way a single phrase which in his opinion distorts the truth.

- Will utter such a phrase neither in private conversation nor in the presence of many people, neither on his own behalf nor at the prompting of someone else, neither in the role of agitator, teacher, educator, nor in a theatrical role.

- Will not depict, foster or broadcast a single idea which he can see is false or a distortion of the truth, whether it be in painting, sculpture, photography, technical science or music.

- Will not cite out of context, either orally or written, a single quotation so as to please someone, to feather his own nest, to achieve success in his work, if he does not share completely the idea which is quoted, or if it does not accurately reflect the matter at issue.

- Will not allow himself to be compelled to attend demonstrations or meetings if they are contrary to his desire or will, will neither take into hand nor raise into the air a poster or slogan which he does not completely accept.

- Will not raise his hand to vote for a proposal with which he does not sincerely sympathize, will vote neither openly nor secretly for a person whom he considers unworthy or of doubtful abilities.

- Will not allow himself to be dragged to a meeting where there can be expected a forced or distorted discussion of a question.

- Will immediately walk out of a meeting, session, lecture, performance or film showing if he hears a speaker tell lies, or purvey ideological nonsense or shameless propaganda.

- Will not subscribe to or buy a newspaper or magazine in which information is distorted and primary facts are concealed.

By contrast, genocidaire

By contrast, genocidaire

The boy looks small in the hospital gown and is almost swallowed up by the bed as he’s waiting to enter surgery.

The boy looks small in the hospital gown and is almost swallowed up by the bed as he’s waiting to enter surgery.

Another birthday tribute from Los Angeles poet, scholar, and friend

Another birthday tribute from Los Angeles poet, scholar, and friend  Though some gems associated with Spooner are doubtless apocryphal, he does seem to have been almost congenitally disposed to mixing things up. He once spilled salt on a tablecloth and immediately poured claret over it. Giving guests a tour of his college, he warned them that a staircase they were about to descend was badly lit, then switched off the weak lighting, and led them down into total darkness. Also, he suffered from albinism, so his eyesight was poor. Reading lectures was a challenge, and he naturally mangled the text from time to time. It was reportedly during a formal address to farmers that he called them “noble tons of soil,” and it was during a speech before Queen Victoria that he said, “Which of us has not felt in his heart a half-warmed fish.”

Though some gems associated with Spooner are doubtless apocryphal, he does seem to have been almost congenitally disposed to mixing things up. He once spilled salt on a tablecloth and immediately poured claret over it. Giving guests a tour of his college, he warned them that a staircase they were about to descend was badly lit, then switched off the weak lighting, and led them down into total darkness. Also, he suffered from albinism, so his eyesight was poor. Reading lectures was a challenge, and he naturally mangled the text from time to time. It was reportedly during a formal address to farmers that he called them “noble tons of soil,” and it was during a speech before Queen Victoria that he said, “Which of us has not felt in his heart a half-warmed fish.”

Julia Fiedorczuk

Julia Fiedorczuk for R. K.

for R. K.

Having been nominated for a prestigious prize, and then lost it, poet

Having been nominated for a prestigious prize, and then lost it, poet  Read the whole thing

Read the whole thing

In a statement, French President

In a statement, French President