I had looked forward to meeting Judy Stone, The San Francisco Chronicle’s movie critic. She wasn’t solely a film buff. The passionate advocate for world cinema also published a number of stunning interviews with leading figures in literature and culture.

I had looked forward to meeting Judy Stone, The San Francisco Chronicle’s movie critic. She wasn’t solely a film buff. The passionate advocate for world cinema also published a number of stunning interviews with leading figures in literature and culture.

While going through old boxes of papers, I stumbled across a xerox I’d made of her excellent and insightful interview with Nobel poet laureate Czesław Miłosz, which was included in her 2006 Not Quite a Memoir: Of Films, Books, the World. I googled her, and learned she was still alive and living in the Bay Area … but not for long. The celebrated critic died in San Francisco on Friday, Oct. 6, of natural causes.

An excerpt from the interview:

In his Nobel address, Miłosz referred to the number of published books that have denied that the Holocaust ever took place, suggesting that it was invented by Jewish propagandists. “If such an insanity is possible,” he asked, “is a complete loss of memory as a permanent state of mind improbable? And would it not present a danger more grave than genetic engineering and/or poisoning of the natural environment?”

Such a loss of memory is probable, he reasons. Referring to the television miniseries Holocaust, he asks with a sense of horror: “Do people really have to see reality changed into melodrama to come a little closer to visualizing how it really was?”

Are we losing memory?

Miłosz has played a role in stimulating different levels of consciousness in Poland – for instance, through his 1958 translation into Polish of the writing of Simone Weil. …

“I have been influenced by Weil in a profound way,” Miłosz says. “Primarily because of her very deep concern with evil. That was her main preoccupation: suffering, pain, the evil of the world. This goes back to my preconceptions when I was a schoolboy. I was interested in heresies which were concerned with evil and with suffering, and Simone Weil is a slightly heretical writer.”

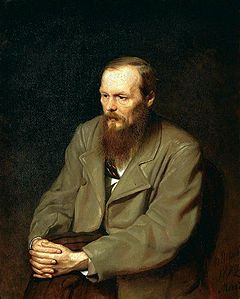

Miłosz’s preoccupation with Weil and Dostoevsky is linked to his meditations on the figure of Job, who dared to question God but whose faith withstood the test of all calamities.

“Job is at the center of Weil’s attention, and I quote at length from her in my introduction to the Book of Job. We are again close to the Book of Job with Dostoevsky. It plays a crucial part in the structure of The Brothers Karamazov. I have never taught other Russian writers. Only Dostoevsky. I laughingly tell my students that Dostoevsky, who hated Poles and Catholics, is taught by a man who is very far from Dostoevsky’s Russian Orthodox views. But I’m fascinated by those deeply felt contradictions in Dostoevsky and his sensitivity to the question of evil. So you see, we are always turning around the same problem.”

“Only Dostoevsky.”

I ask if he sees the world in terms of good and evil.

“Unfortunately, I guess I do,” Miłosz replies. “I have a very clear, very strong feeling of opposed forces of good or evil. It’s something which you acquire only through experience and very elemental. That’s precisely the gist of what Nadezhda Mandelstam says in her memoir. This is characteristic of her and of Solzhenitsyn and all who went through misfortune, affliction. In those extreme situations, good and evil acquire elemental force. Western civilization is losing that clear distinction: Everything can be explained away; everything is relative. In dramatic circumstances, you feel clearly the good forces and the demonic forces in action.”

***

I ask if his wartime experiences in Poland had influenced his decision to translate the Bible.

“To some extent, my memories elude my consciousness,” Miłosz replies. “I suspect it’s been operating on a much deeper level of horror, so translating the Bible is a quite logical way of coping with some subconscious things … like dreams.”

Tags: Czeslaw Milosz, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Judy Stone, Simone Weil