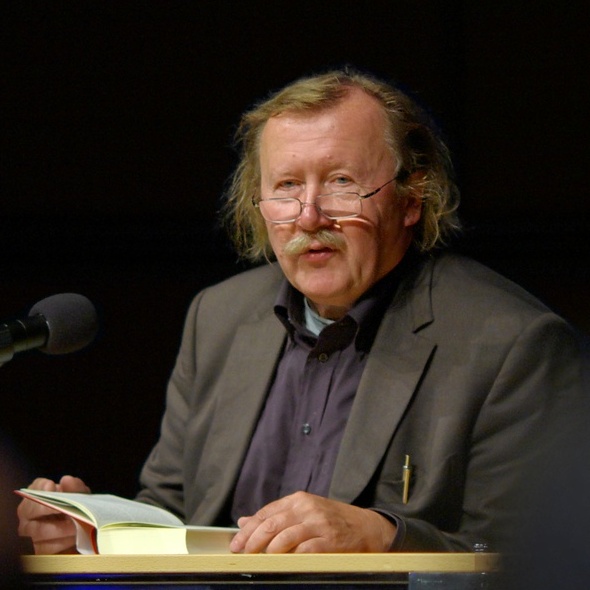

Who is the last man? Peter Sloterdijk on Nietzsche

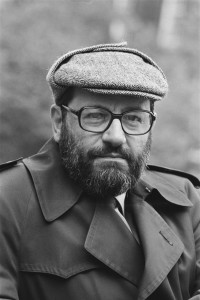

Tuesday, July 16th, 2019 Peter Sloterdijk is one of the most controversial thinkers in the world. In many ways, he is the heir of Friedrich Nietzsche, who is sometimes said to have inaugurated the 20th century. A year ago, the Book Haven published a summary of Sloterdijk’s Entitled Opinions conversation with radio host Robert Harrison. The podcast and summary was also posted at the Los Angeles Review of Books here. In December, we published a full transcript in German at Berlin’s Die Welt. You can read it here. Last week, the Los Angeles Review of Books published the full transcript, in English, here.

Peter Sloterdijk is one of the most controversial thinkers in the world. In many ways, he is the heir of Friedrich Nietzsche, who is sometimes said to have inaugurated the 20th century. A year ago, the Book Haven published a summary of Sloterdijk’s Entitled Opinions conversation with radio host Robert Harrison. The podcast and summary was also posted at the Los Angeles Review of Books here. In December, we published a full transcript in German at Berlin’s Die Welt. You can read it here. Last week, the Los Angeles Review of Books published the full transcript, in English, here.

A few excerpts below:

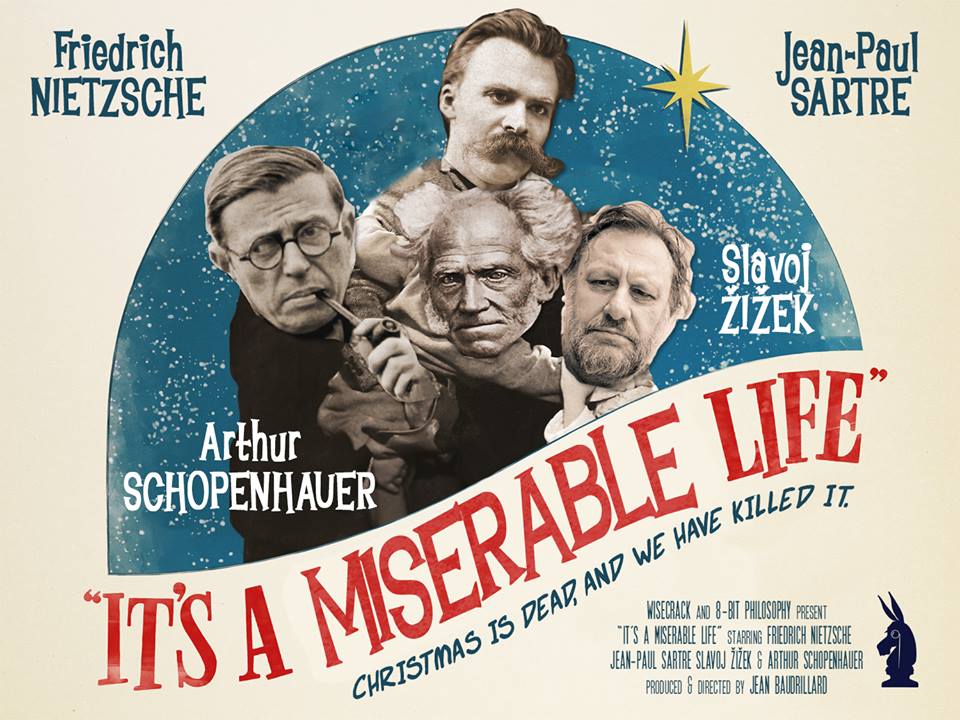

Harrison: I find that when it comes to Nietzsche being a prophet, in some ways he was blind about what would be the most dominant feature of the coming century, though many people consider him the inaugurator of the 20th century. He has almost nothing to say about the dominance of modern technology in the era to come. Okay, you can say that this was a blind spot in his thinking. In Zarathustra, especially in part four, however, he has a prophetic vision that has to do with our own time. He thinks of the last men. Who is the last man? In what way are the parameters of that last man contained within … for example, the consumerist of our own society, who is complacent?

We’re no longer dealing with the petite bourgeoisie or those 19th-century categories. It’s very much the contemporary citizen as a global citizen, a kind of capitalist of consumerism who does not think beyond the creaturely comforts of this day and the next day. There’s something in his thinking that promises to show us a way to transcend this fatality. European civilization after all these centuries and millennia cannot end in the last men. Or will it?

Sloterdijk: Here, in Nietzsche, appears a major problem that will occupy humanity in the centuries to come: the question of how to maintain what I call the vertical tension inside the human being. For everything that has to do with verticality, Nietzsche is the specialist coming from the tradition. He discovered this new type of problem — how to maintain the vertical tension if the higher region has been removed. As if Jacob’s Ladder, over which the angel can march up and down should still stand upright without having the support on the upper level. So there is still height, but no support from above. Everything has to be erected from below. The vertical tension has a rocket-like dynamic, a will to growth, and that can be easily expressed in biological terms. You can go back to Goethe, who said that all life is movement and extension, and from here you get to a less megalomaniac conception of growth.

Harrison: Well, in fact, in Nietzsche Apostle, you speak about his extraordinary genius as a marketer of his own brand. You don’t merely invent a brand that then takes off in the market. What you do is create the market for the very brand that you’re promoting. And Nietzsche created a market for a brand of … I think it’s related to what you’re talking about, the ladder of having realized that — in the regime of the last man, a regime of egalitarianism — there will always be a drive for distinction. He marketed his philosophy as a promise, as a way to understand a need before it even became apparent to the world itself, that there was going to be a need for distinction in this world.

But you also say, somewhat prophetically, that he was promising losers a formula by which they could be on the side of winners. This was also part of his brand. Can you say something about this? When you speak about verticality, are you speaking about this need for distinction in this particular regime?

Sloterdijk: I think Nietzsche was among the very rare thinkers who had a feeling for the deep connection between moral philosophy and public relations. This can be shown by the subtitle of Zarathustra: Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen — “A Book for All and Nobody.” And I’m convinced that this is Nietzsche’s genius. This subtitle betrays something of his innermost drive. His way of polemics, as Heidegger would put it, was not really polemics. It was teaching, and so it was a kind of “action teaching” — action teaching like Joseph Beuys would call his performances. Nietzsche was a kind of action teacher writing a book for all and nobody, and discovering in so doing the very structure of higher morality.

This kind of morality creates a field of behavior that is not applicable to living populations but traces the horizon for new generations to inhabit. This necessarily has to be a challenge, just as Buddhism was before it was brought out as an Indian form of gospel, as a way of salvation, just as the Christian Gospel was a pure challenge to the pagan environment of the former world. And so Nietzsche designs a horizon for those who in the morality markets of the future will distinguish themselves as individuals who show how the path of humanity can be continued. And in that context, you read this most provocative sentence from the introduction, the so-called prologue to Zarathustra: “Man is a rope between the animal and the Superman,” and you decide if you want to be a successful rope-walker or not. And if you are not successful as a rope-walker — you have nevertheless tried it.

That is the meaning of this philosophical pantomime that concludes the prologue of Zarathustra. He sees the rope-walker who has fallen down, and he says, “You made the danger. Out of danger you made your profession. There is nothing to despise in that, and for that reason I am going to bury you with my own hands.” That is Zarathustra’s message. It’s not success that decides everything. It is the will to remain within the movement and to walk on the rope, if you do not want to remain a part of the masses that are looking up and admiring people doing crazy things.

Read the whole thing here.

My review is online at The New York Times Book Review today

My review is online at The New York Times Book Review today

What better way to celebrate Christmas than with a secular Turkish-American writer discussing

What better way to celebrate Christmas than with a secular Turkish-American writer discussing