d.compress: Designing for discovery & intent

Students gathered at the d.school at the end of the 2014 fall quarter to participate in d.compress — an event meant to help them synthesize the previous quarter and look forward with intent. (Olivia Vagelos)

A workshop was held at the d.school just before students left for the holidays. Aptly called “d.compress”, it offered students an opportunity to retreat from the stresses and pressures of the fall-quarter finals period.

The event was organized by d.school Course Production Lead and Stanford alumna Tania Anaissie and Stanford alumna, designer and entrepreneur Olivia Vagelos. Invitations were sent out to the d.school community with a sign-up sheet. The event was geared primarily towards students and, as the weather turned rainy, came with the offer of hot chocolate and cookies.

Curious, I signed up.

We gathered in the media production studio (nicknamed “Studio 4″) on the second floor of the d.school. The room is small, cramped and generally locked. But Olivia and Tania transformed the space into a lounge. There was soft lighting, music and, yes, hot chocolate and cookies.

The participants came from a variety of educational ranks — everyone from undergraduates, to graduate students and fellows.

The group was large but still fit the space. Olivia and Tania took us through a getting-to-know-you game called “Party, Park, Jail.” The exercise was meant to help students get to know one another, open themselves up more so than they otherwise would and acknowledge who and where they were in that particular moment in time.

We were then asked a series of questions, such as:

- What do you spend a lot of time doing?

- What are you good at?

- What do you enjoy doing?

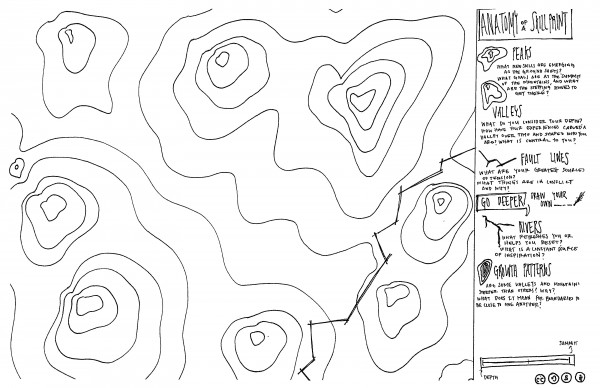

Then, based on the answers, we filled in a map — the skill print. We were given a scaffold in the form of a 2-dimensional topography. Peaks represented emerging skills. Valleys represented the skills you felt more confident in. Peaks were represented by one color, valleys by another. You could add extra growth patterns to show steeper inclines and declines. You could shade in the levels differently, with darker shading representing steeper gradients.

Fault lines represented points of great tension or conflict. Rivers were meant to show what helped to refresh or replenish you.

The map students were given in d.compress to represent their skills, both deep and emerging, their stress points and more during a workshop held prior to winter break at the d.school. (Olivia Vagelos)

If the skill print sounds familiar, that may be because you’ve encountered it as one of the four prompts from design work conducted at the d.school. This body of work has come to be known as Stanford 2025. The work was done to explore the future of living and learning at Stanford. The skill print — an idea that emerged as a potential replacement for the transcript — emerged from that.

This isn’t the skill print, of course. That doesn’t exist — at least not yet. This is a prototype Olivia and Tania developed for the purposes of the d.compress exercise. Someone else may imagine it to look and feel differently — a finger-print, say, instead of a topographical map.

- Students participate in the d.compress event, filling our their maps in words and colors. (Olivia Vagelos)

- A model of the map shown to participants during the d.compress workshop held at the d.school this past fall. (Olivia Vagelos)

- The scene while planning for the d.compress workshop. (Olivia Vagelos)

- Students participate in the d.compress workshop at the d.school just before the end of the 2014 fall quarter. (Olivia Vagelos)

The goal was to create a tool for discovery rather than display. Olivia and Tania sought to answer this question: How might you get people to surprise themselves, find new connections and make new meaning out of what they have.

“We wanted this exercise to be a chance for students to reflect on skill sets they’ve developed up to this point and also an opportunity for students to gain clarity around what skills they want to further develop moving forward,” said Tania via e-mail. “We hoped this would help them plan their next quarter and remainder of time at Stanford with intent.”

The 23-year old designers and former classmates toyed with a string map before settling on a topographical one. They also decided to give everyone the same starting map (above). The goal was to have a static representation of a dynamic system with the finished product being a snapshot of an individual’s experience.

In terms of the map itself. There was some debate as to whether the map should be two dimensions or three. They settled on a two-dimensional map representing three dimensions.

Olivia was excited by the idea of a physical, 3-dimensional map with fully-realized peaks, valleys and fault lines. But she recognized that raising the resolution of the map introduced a tension. On the one hand, a higher-resolution map could give someone greater creative agency and grow their creative confidence. Then again, it could also leave someone feeling disappointed if they failed to have their grand vision well-articulated.

That said, Olivia and Tania were surprised at how inclined participants were to be visual and less verbal on their maps. The team expected people to write more, instead they drew more. The duo was surprised by how easy it seemed to be for participants to fill in the fault lines.

“Usually it is difficult for people to admit and articulate weaknesses and insecurities,” said Olivia, “I think there was something in the framing of it instead as “tension” that was important.”

When asked what they would change, Olivia turned to the map’s peaks and valleys. “There were so many valid ways to interpret this metaphor,” she said, “but then you also have to pick at some point.”

There was also the question of how detailed of an example they should give. “We would have liked to give them a more specific example of a peak and a valley that was more story-based and narrative-based.”

If you are interested in conducting a similar exercise with your students, community or organization. Here’s Olivia’s recommendation: “Push yourself to make meaning out of the opportunities of the metaphor. … Give yourself the opportunity to go there.”

Also, don’t feel constrained by the tool provided here. “This is just a baseline,” said Olivia. “My goal is to always try to surprise yourself and let yourself go down the rabbit hole a little bit. … Don’t just stay on the surface.”

Creating space for idea capture

by Emi Kolawole|January 15, 2015

1 Comment

Open these: links for open policy makers (week 28) | Open Policy Making

[…] Kolawole enjoyed an exercise to design for self-discovery (HT […]