A place for design thinking in academic research

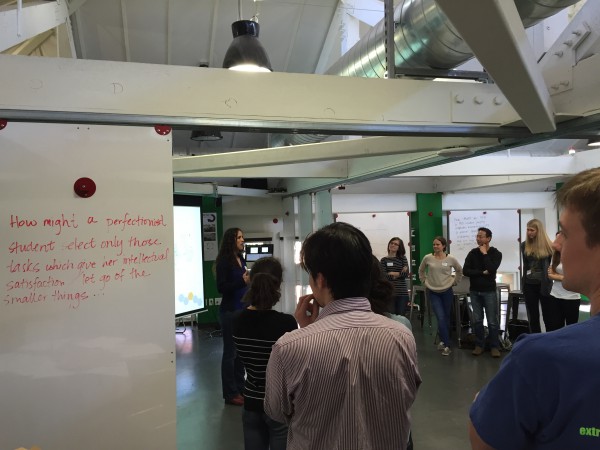

The second class of “Research as Design” begins. The class explores the application of design thinking in professional research. (Emi Kolawole)

Can design thinking help people do better research and better science?

Enter the d.school pop-up class “Research as Design: Redesign Your Research Process“, which was taught this past winter. The class provides PhD candidates, post-doctoral researchers, master’s degree candidates, faculty and others engaged in professional research at Stanford an opportunity to learn how they may apply design thinking to their work.

The instructors seek to help their students discover needs and explore potential solutions to problems in their research efforts. Prior to the class, I spoke with Amanda Cravens, a collaborative technology specialist and researcher at Stanford Law School. Along with the other members of the class’s teaching team, Nicola Ulibarri, Anja Svetina Nabergoj and Adam Royalty, Amanda has been conducting research around the role design thinking could play in the world of long-form research (PDF).

A problem of one and many

“Research is very much an individual problem, especially for PhD students,” Amanda told me. The goal of the class is to make finding the solution to that individual problem a collaborative effort.

The class explores the larger question of how this population’s emotional needs might be understood and addressed. It’s a change from the common approach, which is to take care of people’s mental health needs individually and separate from their research.

Amanda and I agreed that I should sit in on a class to see how they teach design thinking to this community. I agreed, fascinated by the idea of paving a vibrant and dynamic pathway to creative agency in the world of graduate research — a world I had come to see as overly constrained and staid.

I arrived to a full classroom of academics in a variety of fields, including biology, robotics and environmental science. Each d.school class must have a mix of students from a variety of disciplines. This class had that, but it also had a common thread in that everyone in the class was involved in research in some way. Students from the law school, business school and engineering school may have been different in their pursuits, but they had a natural point of empathy: the challenge of research. That commonality made for a unique class environment — one where empathy was almost automatically present from the beginning.

Solving someone else’s research challenge may, in fact, mean solving your own.

Quiet confidence

The class was taught in a much calmer mode than I was used to for a d.school class, but that was the teaching team meeting their students where they were. They had to in order to bring them to a new and, perhaps, more uncomfortable place. The quiet was in no way an indication of a lack of enthusiasm either. Students were actively involved in every exercise. They did their collaborative and heads-down work with purpose.

The class started with empathy interviews and need-finding. Students paired off and interviewed one another. They then moved into defining the problem their partner faced in their research. Students interviewed one another again and then engaged in a why-laddering exercise to ascertain underlying needs.

The why-ladder, for those not familiar, is a process where you post a problem statement and then challenge that statement by asking “why” at least five times. When I asked the class how many students had used a why ladder before, no one raised their hands. The lesson was entirely new.

Eventually, each class member arrived at a “how might we” statement.

Here’s an example:

“How might we improve the confidence of a very talented researcher”?

Let’s pause here. The word “confidence” or variations on the theme of empowerment dominated in classroom discussions and notes. That the topic arose wasn’t surprising. It’s prevalence, however, was striking.

Amanda (middle ground) sits with students as they learn to apply design thinking to their work. (Emi Kolawole)

A personal journey

Amanda had warned me before the class that that one of the least accounted for aspects of research work was the emotional toll the process can take on the researcher. She had first-hand experience with this phenomenon when she was working to complete her PhD.

During that time, she and her teaching teammates had applied design thinking in their own work, biasing towards sharing ideas and creating their own multidisciplinary, collaborative teams to help one another work through problems. Their practice, however, was unique for their respective fields at the time.

They have since found, through their own experience and further research, that being proactive about emotional needs leads to greater productivity. Amanda now has five tips for researchers who seek to bring design thinking into their work:

- Stop and reflect: Continually ask yourself “What’s going on?” and “Where are you?”. This means adopting a habit of mindfulness, sometimes placing process over goals.

- Find people: Set up your environment so you are not alone. Find a team. If you can’t find one, create one.

- Pay attention to your emotions: What roles are they playing in and around your work? What would it take to turn things around? What do you need to add or subtract from your life so you can be happy and vibrant and creative enough to do amazing work?

- Embrace the idea of failing early and failing often: In academia, the feedback cycle can be six months to a year long, and the fear of failure is often incredibly intense. The moment you have something you can share— anything — get out there and show somebody. You might as well get feedback early so you have more time to improve it rather than striving for perfection on your own.

- Identify to whom in your network you can show your early attempts and drafts: You can’t always show just anyone anything, but be sure to identify those people with whom you can be the most open. What stage of “finished” does your advisor need in order to give you useful feedback? Your labmates? Your grandma?

Students gather at the end of class to discuss their experience learning to apply design thinking to high-end research. (Emi Kolawole)

The number of “how might we” statements around the topic of confidence during the day’s class cut to the heart of one of the d.school’s underlying goals: fostering creative confidence. Research is, at its core, a hunt for discovery and insight. It is even a core component of the design thinking process in the form of empathy interviewing and need-finding.

The class eventually went from defining problems to brainstorming potential solutions with a series of constraints. During one point in the brainstorm all responses had to involve a tree where, at another point, ideas had to cost at least $1 million. The first half of the six-hour class session focused primarily on teaching students about the design thinking process.

The second half of the class drilled in on the define phase of the process, starting with the Charles & Ray Eames video “Powers of Ten” — an exploration of magnitude:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fKBhvDjuy0

Students were then called on to re-define their partner’s problem, looking at actions their partner could take in an hour, a day, a week, a month or even a year to reach a solution.

Eventually the students moved to prototyping and on to presenting their ideas. The class day ended six hours after it started, with students having gone through two design rotations. There were, by the end of class, a number of ideas strewn across numerous whiteboards as well as prototypes and their remnants covering tables. The students, all disciplined scholars, appeared exhausted but satisfied.

The class meeting, a rapid and robust tour through the design thinking process, was the second of four sessions.

This was a very different classroom experience than any I had witnessed since coming to the d.school. Everything from the quieter but still intense classroom energy to the unique mix of students with a common problem thread, highlighted how myriad the applications of design thinking can be.

If you are in the midst of research and have questions about the application of design thinking on your work, feel free to pose them in the comments or tweet them to us at @stanforddschool.

Learn to teach the d.school way: Apply to be a teaching fellow!

by Emi Kolawole|March 24, 2015