The Master of Materials

For Associate Professor Yi Cui, better materials mean better batteries, solar panels, renewable power storage and more.

To meet Yi Cui is to be immediately struck by two things: the extraordinary breadth of his interests, and his drive to design new materials that could change our world.

The associate professor of Materials Science and Engineering is currently pursing research that could lead to lighter, longer-lasting and more powerful portable batteries, new storage solutions for renewable power generation, super-thin solar panels, flexible display screens, printable and transparent batteries and innovations, such as new methods of water filtration and nano-biological interface.

What’s more, Cui has a good chance of making genuine advances in each of these fields. He’s already established a name as the inventor of a technique that could improve the capacity of conventional lithium batteries by a factor of 10, earning himself the moniker ‘the battery master.’

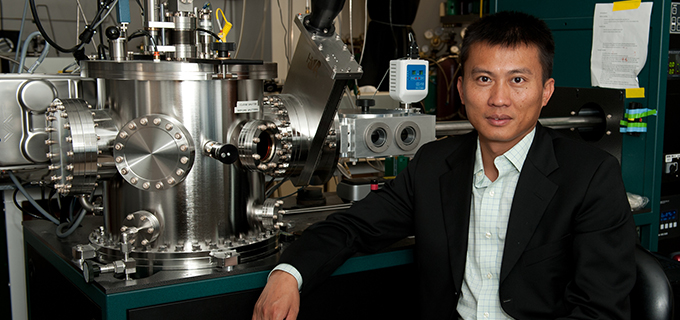

Yi Cui, associate professor of materials science and engineering. Photo: Steve Castillo

Cui’s many interests are hardly scattershot. Most involve the manipulation of materials at the nanoscale. And they’re all born from a fundamental turn in Cui’s thinking that occurred when he joined the Stanford faculty in 2005.

“As a graduate student, I was interested in nanoscience and nanotechnology,” he recalls. “We produced beautiful new materials like nanowires and nanocrystals, but they didn’t always have an obvious use. After I joined Stanford, I decided to look first at what society really needs and then to ask whether we could design better materials to address those problems. And, in many cases, the answer has been ‘yes.’

Towards better batteries

One of the first nanoscientists to apply an engineering perspective to the field, Cui initially took on the challenge of improving lithium ion batteries. It was a completely new direction for him – a bold move considering he’d just entered a tenure track position.

“Some seven years ago, I realized that batteries were going to be very important in addressing our energy issues,” Cui says. “You need high-energy batteries for portable electronics or for electrical cars. You want to store a lot of energy per unit weight and volume. But at present our batteries really aren’t that good.”

Lithium ion batteries consist of two electrodes – a positive cathode and a negative anode – separated by a lithium salt electrolyte. The anodes are typically made from graphite, even though it’s long been known that silicon would bind with (and thus store) 10 times as many lithium ions as carbon. That’s because silicon expands significantly and breaks when it stores lithium, rendering it all but useless as a battery component.

Thanks to his expertise in nano-synthesis, however, Cui had a hunch that he could make silicon work.

“My immediate reaction was that if you make silicon into wires of very small diameters, they probably would not break,” he says.

So Cui began building a silicon nanowire electrode. Eventually, he and his research team created silicon nanotube anodes coated with silicon oxide shells that not only had a much higher storage capacity, but could also last six times longer than conventional graphite anodes. Just recently, they announced a new ‘yolk-shell’ design that promises the same improved performance while also being easier to manufacture. Cui thinks silicon has promise for use in commercial batteries.

More battery innovations

Next Cui wanted to improve to the lithium ion cathode. Here, he turned to sulfur, another material that stores lithium 10 times more efficiently than the existing lithium cobalt oxide cathode. But sulfur is an engineering nightmare to work with. Like silicon, sulfur expands on contact with lithium. Its intermediate reaction products will also dissolve in the electrolyte. Plus, sulfur and the lithium sulfide compound it forms are poor conductors.

Again, Cui turned to nanoscience to make functioning sulfur cathodes. Last year he and his students debuted a long, but just 200 nanometers wide, hollow carbon nanofiber that could constrain sulfur expansion but still allow lithium ions to pass through them and be stored.

They expect to announce a second generation of nanomaterial cathode designs very soon. Cui also is investigating energy storage on a much larger scale, this time in collaboration with Emeritus Professor of Materials Science and Engineering Robert Huggins, emeritus professor of materials science and engineering. They’ve jointly published widely-noted research suggesting that an electrode made of crystalline nanoparticles of copper hexacyanoferrate might be used to create cheap and long-lasting batteries that could help integrate wind or solar power generators with the electrical grid.

Most battery research remains focused on portable storage where weight and size count for a lot, notes Huggins. “We set out to work in a different direction, on materials and systems and concepts that are more relevant to the grid. It’s very important.”

“He’s always in motion,” Huggins says of Cui. “He works very hard and he’s highly innovative. He’s really a leader in nanotechnology.”

Beyond batteries, Cui and his collaborators have developed printable electrodes that can be used in super-capacitors, and applied their expertise in nanowires to create conductive meshes that could be used to make thin-film solar cells, textile- and paper-based batteries, transparent electronics, and, most recently, bendable touchscreens.

They’ve even branched out into environmental technology, developing a water filter that uses electricity to kill bacteria.

Rational materials design

Cui says his innovation process is guided by what he calls ‘rational materials design.’

“First, I have a problem I want to address,” he explains. “Then I take the fundamental scientific principals, my knowledge of materials and my intuition – and I come up with a design for the materials to address the problem.”

In 2008, Cui founded a startup, Amprius, to commercialize the silicon anodes that he’s developing. That’s given him a still deeper insight into the engineering problems that have to be resolved before a theoretical solution can become a usable product.

Back at Stanford, Cui was awarded a Sloan Research Fellowship and named a David Filo and Jerry Yang Faculty Scholar in 2010. In 2011 he was awarded Harvard’s Wilson Prize in chemistry. He also maintains a visiting professorship at the Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

A busy lab

Given the man in charge, it’s no surprise that Cui’s lab in the Gordon and Betty Moore Materials Research building at Stanford is a hive of activity. Some three dozen post-doctoral researchers, graduate students and undergraduates are busy at banks of machines designed to build, analyze, separate, cook, coat, print, measure and otherwise manipulate materials at the nanoscale.

Post-doc Kristie Koski knew Cui when she was majoring in chemistry at UC Berkeley and when Cui was undertaking his own post-doctoral research. She remembers regularly needing to check a nuclear magnetic resonance experiment in the middle of the night. “I’d be walking around the halls of Berkeley at 3:00 in the morning,” she recalls, “and Yi would be there. He was that dedicated.”

While he’s rarely in the lab at 3:00 a.m. any more, Cui’s constantly mulling new ways to solve interesting, practical problems. “Even when I go home I’m thinking about it,” he says.

He’s glad to have held on to the fundamental curiosity that he had a child growing up in China, well before its more recent surge of economic wealth.

“We didn’t have the luxury of anything like a chemistry set to play with, but I’ve always been fascinated by phenomena and wanted to ask the question, ‘why?,’ ” he says. “If I can make a difference to a human life, that excites me as well.”

Last modified Fri, 16 Nov, 2012 at 10:19