Originally posted in ReMix: The Stanford University Libraries Newsletter

Sixteen volumes selected from among the Libraries’ “beautiful books” were recently added – approximately 1,400 images in all – to the Stanford Digital Repository, where anyone can

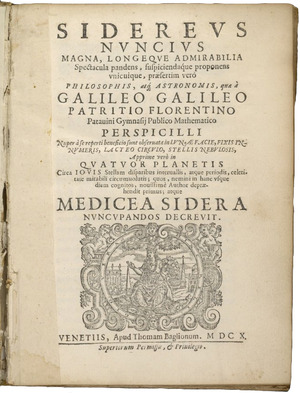

now view Renaissance artistic visions of the fall of Troy, see the universe as Galileo showed it to hiscontemporaries, hear Dr. Johnson pitching his idea for the first serious English dictionary, and admire one of the last magnificent examples of the golden age of English fine printing just before WWII. As with all of Stanford’s rare and antiquarian books, the printed originals of these digitized volumes are cataloged inSearchWorks and can be requested for viewing in the Special Collections reading room. Now, via each item’s PURL (persistent uniform resource locator, which ensures that these materials are available from a single URL over the long term), researchers can work with digital as well as original printed editions. Scholars have discovered, though, that each has its own advantages and disadvantages, and often find it useful to consult both in their work.

Rare books curator John Mustain, who selected items for the repository, explained the origin of the “beautiful books” designation: “In fact, the naming of this project was done without extensive thought and deliberation. The first book scanned, the 1483 edition of Pliny’s letters, was done before the beautiful books project (or its name) had been fully conceived. After the job was finished, a colleague, Stu Snydman (manager of digital production and web application development), told me that the Pliny was a beautiful book, and he suggested that we scan more such items, scan them as a formal project, books with marginalia (as the 1483 Pliny has), books with interesting provenance, books esteemed for their beauty. When I asked him what we would call the project, he answered without pause “Why not ‘beautiful books’?” In this way the project was launched and the name chosen.”

Pliny’s letters, was done before the beautiful books project (or its name) had been fully conceived. After the job was finished, a colleague, Stu Snydman (manager of digital production and web application development), told me that the Pliny was a beautiful book, and he suggested that we scan more such items, scan them as a formal project, books with marginalia (as the 1483 Pliny has), books with interesting provenance, books esteemed for their beauty. When I asked him what we would call the project, he answered without pause “Why not ‘beautiful books’?” In this way the project was launched and the name chosen.”

There are many questions – some suggested by this digitization project itself – about the nature and beauty of books which could be posed here and about which our readers might debate. What makes a book beautiful? The Collection of Seventeen Greek and Latin texts, for example, is hardly attractive by conventional standards but is a splendid visual artifact, akin to archaeology, of Renaissance education. Does reading a work in a beautifully printed edition affect appreciation? Some collectors, for instance, read the works they collect in common editions in order to preserve their valuable copies in pristine or sometimes uncut condition. Is a first edition or a deluxe edition preferable to a Penguin paperback? Some readers prefer the portability and handling of paperbacks, and might even call them beautiful, especially their cover art. Can digital versions, which cannot be touched or smelled, adequately represent the beauty and antique qualities of early printed works? See further, on this question, the link in our News & Views section to anarticle on the bibliographic and social codes in printed books. Should we prefer an antiquarian copy as printed during or shortly after an author’s lifetime to a recent edition benefiting from textual criticism and scholarly annotation? I suppose that depends mainly on one’s purpose in reading. Finally, does illustration, since many equate “beautiful books” with “illustrated books,” enhance meaning in a literary work? Illustrations in post-mortem editions usually seem to represent the author’s intentions, but perhaps not always. Many other questions could surely be asked, if not answered, here.

editions in order to preserve their valuable copies in pristine or sometimes uncut condition. Is a first edition or a deluxe edition preferable to a Penguin paperback? Some readers prefer the portability and handling of paperbacks, and might even call them beautiful, especially their cover art. Can digital versions, which cannot be touched or smelled, adequately represent the beauty and antique qualities of early printed works? See further, on this question, the link in our News & Views section to anarticle on the bibliographic and social codes in printed books. Should we prefer an antiquarian copy as printed during or shortly after an author’s lifetime to a recent edition benefiting from textual criticism and scholarly annotation? I suppose that depends mainly on one’s purpose in reading. Finally, does illustration, since many equate “beautiful books” with “illustrated books,” enhance meaning in a literary work? Illustrations in post-mortem editions usually seem to represent the author’s intentions, but perhaps not always. Many other questions could surely be asked, if not answered, here.

We can more easily agree, I imagine, that beautiful books are integral to the concept of culture; indeed, they are often said, particularly for the illustrated and illuminatedmanuscripts of the ancient and medieval periods, to best represent  national cultures andaesthetic norms. These same manuscripts are often displayed in museum cases today and have retained their ability to touch lives, even of those who never read the works contained in them.

national cultures andaesthetic norms. These same manuscripts are often displayed in museum cases today and have retained their ability to touch lives, even of those who never read the works contained in them.

Presented below, in chronological order, are digital offerings ranging from a 1490 incunabulum through a 1939 British fine press printing ofPervigilium Veneris (illustration, right), a fourth-century Latin poem celebrating the arrival of spring with its famously poignant refrain:

Cras amet qui numquam amavit, quique amavit cras amet.

Loveless hearts shall love to-morrow, hearts that have loved shall love once more.

In the spirit of this poem (adapted for booklovers), please accept our invitation to enjoy one of these beautiful books.

Selections from "Beautiful Books":

Sphaera mundi, 1490, by Joannes Sacro Bosco (fl. 1230), with astronomical illustrations.

Proverbia Senece, 1495, an alphabetical compilation of proverbial sayings (sententiae) from Seneca’s works.

Historia Troiana, 1498, the fall of Troy in the Latin version attributed during the Middle Ages to Dares Phyrgius.

Parthenice, 1499, Baptista Mantuanus’s life of Mary in epic language.

In Robertum Seuerinatem panaegyricum Carmen, 1499, also by Baptista Mantuanus.

Operetta del amore di Iesu, 1505, by Girolamo Savonarola.

Collection of Seventeen Greek and Latin texts, 1543-1544, various portions of classical texts issued as pamphlets with wide margins and generous line spacing for use of students and heavily annotated throughout.

Icones historiarum, 1547, containing Hans Holbein’s 94 woodcut illustrations of the Old Testament designed at roughly the same time as his 41 engravings of The Dance of Death.

Sidereus nuncius, 1610, containing Galileo’s sketches of the moon and the first scientific treatise based on observations made through a telescope.

A Collection of Emblemes, 1635, by George Wither, with 200 plates of emblems engraved by Crispin de Passe.

Innocentia vindicata, 1695, by Celestino Sfondrati, with 46 full-page emblematic copperplates with devices within cartouches of various designs.

Book of common prayer, 1717, Church of England, engraved throughout.

Plan of a dictionary of the English language, 1747, by Samuel Johnson.

Miseries of Human Life, 1809, by T. Rowlandson, from the “golden age of caricatures” (1780s-1830s).

Characters in the grand fancy ball, 1828, with hand colored line engravings of costumes drawn from the works of Sir Walter Scott and Baron La Motte Fouqué.

Pervigilium Veneris, 1939, one of 100 numbered copies with engravings by John Buckland-Wright and issued by the Golden Cockerel Press, side-by side Latin and English.

Add comment