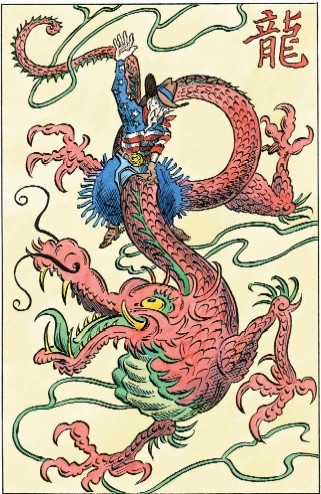

The Dragon Next Door

Once again there is talk in Washington that the United States should treat China as a dangerous adversary, a militaristically aggressive power like Germany in the 1930s. Former secretary of state Henry Kissinger, however, has correctly called such an approach “unwise.” A policy of “containment” would only increase the threat of war in the Pacific and undermine the chances of dealing constructively with conflicts of interest.

We should try instead to build a cooperative relationship with China. Two kinds of problems seem to prevent such a relationship, but they have been exaggerated. First, it is true that the United States faces a huge challenge competing in the globalized economy with a nation in which a well-educated and increasingly affluent population sector about the size of the whole U.S. population enjoys an endless supply of cheap labor and makes increasing demands on the world’s scarce resources, notably oil. I believe, however, that the American business world has the technological and entrepreneurial resources to meet this challenge.

Second, many Americans are concerned with the way that Chinese policies actually or potentially conflict with U.S. interests in peace on the Korean peninsula, the security of Japan, the security of Taiwan, and respect for international law in Southeast Asia. Again, however, there are no insuperable problems in this regard. The pursuit of U.S. interests in these cases depends on our retaining the naval primacy in the Pacific that we won in World War II, which China is not going to challenge in the foreseeable future. Moreover, there are no irresolvable disagreements between the United States and China in any of these cases. The threat posed by North Korea is a product of North Korean, not Chinese, behavior. As for the problem in the Taiwan Straits, China and the United States could clash if Taipei defied Beijing by taking decisive steps toward independence, and if Beijing then took military action against Taiwan. Such a nightmare, however, is unlikely. For many years now, relations between China and Taiwan have been moving toward peace and economic interdependence.

| The Chinese are unable—habitually and culturally—to view as normal the international network of power centered in the United States. |

The real source of tension between Beijing and Washington is usually overlooked. It lies outside these two types of problems and dangerously impedes pragmatic efforts to resolve them. It consists of the way that the United States and China are currently locked into ideological visions demonizing each other. This ideological impasse will aggravate U.S.-Chinese relations still more in the next decades, when these two nations will probably have conflicts of interest regarding ever more formidable problems, such as those about energy resources. We and the Chinese, therefore, should minimize this ideological impasse in order to deal as reasonably as possible with our concrete conflicts of interest.

Mutual Demonization

The nature of this impasse is complicated and little understood. First of all, when one looks at the whole spectrum of publicly articulated opinion in China—official and nonofficial, Marxist and non-Marxist—one finds a deep ambivalence about the West, especially the United States.

On the one hand, the desire in China to emulate Western modernity is widespread and far stronger than in the Muslim world. Ever since the late nineteenth century, when the Chinese discovered that Western nations were wealthier, more powerful, and freer than China, they have used Western ideas to criticize and change themselves. Strong affinities exist between Chinese and American ways of life because both cultures tend to put individual merit above inherited social position. Modern Chinese culture also resembles ours in its emphasis on critically scrutinizing and revising traditional ways, wavering between healthy skepticism and impulsive iconoclasm. (Those traits are far from universal in the world today.) Moreover, the Chinese are aware that we stayed out of the imperialistic scramble for power in China before 1949 and helped them overcome Japanese imperialism during World War II. To this day, these memories color interactions between Chinese and Americans on many levels. The Chinese also have a tradition of realism and flexibility in the management of foreign relations and for now are willing to play an international role secondary to that of the United States, the world’s most powerful nation.

On the other hand, in China today runs a strong current of opinion highly critical of the Western model of capitalism and democracy. Many Chinese object to the glaring inequalities produced by capitalism and the individualistic freedom on which capitalism thrives, what the Chinese call li-ji zhu-yi (putting primacy on selfish interests). Most important, the Chinese have largely rejected or misunderstood the modern Western concept of legality fundamental to capitalism. Mainstream Chinese intellectuals are enthusiastic about “the rule of law,” but by this they mean laws that are fully moral and rational, not scrupulous respect for the letter of the law even when it is perceived as irrational. Thus the Chinese are uncomfortable with both the idea of legality as the rules of the game in a capitalistic and democratic society and the idea that individuals morally playing this game normally pursue their own self-interest.

| We know much too little to tell the Chinese how to deal with the enormous complexities of their political development. We should admit as much. |

To be sure, Chinese pursue their selfish interests as much as Westerners do, but they deplore this, insisting it is not what they want. Clearly utopian, their goal is to unleash the dynamism of a market economy while improving on Western modernity by minimizing selfishness and inequality. The Chinese, moreover, apply this moralistic outlook to international relations and also combine it with an emphatically teleological vision of history, believing that there is a “global tide of events” (shi-jie-de chao-liu) moving toward an era of international harmony free of the pursuit of selfish interests. Thus they cannot see normal international relations as a process of bargaining between nations all pursuing national self-interest. Instead, they define it as a struggle between altruistic nations (such as China) moving with the tide of history toward an era of international harmony and nations (such as the United States) resisting that historical tide by pursuing national self-interest at the expense of other nations. Even while respecting the United States as a model of modernization, the Chinese see it as a hotbed of capitalistic selfishness, inequality, and “hegemonism.”

| All of us in the world of Western capitalism see each other as neighbors with a shared sense of decency and civilization. This comforting feeling of neighborliness is missing when we look out across the Pacific. |

To be sure, the Chinese are capable of pragmatically adjusting their policies to minimize conflict with the United States. Nevertheless, they are unable—habitually and culturally—to view as normal the international network of power centered in the United States, not to mention any combination of this network with the use of military force, as in our current war in Iraq.

The Chinese, then, are uncomfortable with the way that the Pacific has become an American lake, not to mention the way that the United States has used diplomacy and military means to surround Asia with a belt of power reaching from NATO to the U.S. alliance with Japan. This Chinese ambivalence about the global role of the United States is reinforced by the Chinese sense of their own global centrality, which China’s George Washington, Sun Yat-sen, summed up as China’s obligation to “save [itself] . . . and save the world” (jiu zhong-guo, jiu shi-jie).

To be sure, there is common ground between some of these Chinese views and the whole Western tradition of self-criticism, not to mention between the Chinese and the American criticisms of President Bush’s policy in Iraq. Nevertheless, most Americans see as absurd any idea that China’s mission is to “save the world” by spreading the Buddhist and Confucian vision of morality and international harmony; China’s claim that it is abnormal for nations to pursue national self-interest; and China’s express discomfort with the projection of U.S. power throughout the Pacific and along the coast of Eurasia.

| Totalitarianism depends on fear. Visit China and you’ll meet one person after another who has no such fear. |

Most important, if one wants to talk about who is responsible for saving the world, Western culture denies that this could be the responsibility of a non-Western people. The American consensus is that this job belongs to the United States. Both the Democratic and Republican Parties strongly support the idea that U.S. foreign policy should aim to realize human rights and democracy throughout the world. President Bush did not invent this idea, he just combined it with the idea of fighting terrorism. By defining all undemocratic governments as evil, or at least abnormal and awaiting democratization, the Bush administration demonizes the Beijing regime as surely as Beijing demonizes the United States. Indeed, the Bush administration is not bashful about linking its China policy with its ongoing effort to seek the democratization of any nation with a different form of governance.

Thinking the Unthinkable

Given this clash between fundamental Chinese and U.S. perspectives on the international world, it is easy to see why the two sides can only tentatively mute the tension between them, instead of forthrightly and pragmatically dealing with their concrete conflicts of interest. We Americans thus are dangerously locked into a view of our Pacific neighborhood that is much more pessimistic than that of our Atlantic neighborhood.

To be sure, some of our European friends can be obnoxious, especially those supercilious French, and scholars like Timothy Garton Ash have sensitively explored the tensions preventing the optimal coordination of U.S. and European policies. Basically, however, all of us in the world of Western capitalism see each other as neighbors with a shared sense of decency and civilization, and this comforting feeling of neighborliness is missing when we look across the Pacific.

There are obvious reasons why it is missing, but it is dangerous to assume that the Pacific area will always be a less friendly neighborhood than the Atlantic. Such a gloomy assumption can become a self-fulfilling prophecy and aborts the possibility of building on the historical and cultural tendencies in the United States and China that could bring us closer together. To build on them, the key step is to disentangle the concrete issues on which we disagree from the ideological views with which we demonize each other. This will require both sides to start thinking what so far has been unthinkable.

On the Chinese side, the unthinkable is the idea of international relations as an arena where national self-interest can only be channeled toward a certain standard of legal, reasonable behavior, not eliminated, and where it is normal for developments such as World War II to create patterns of unequal international power that can only slowly evolve, such as the current naval primacy of the United States in the Pacific. Although many educated Chinese will say there is nothing wrong with this view, it contradicts the rhetorical mainstream of their nation.

| By defining all undemocratic governments as evil, or at least abnormal, the Bush administration demonizes the Beijing regime as surely as Beijing demonizes the United States. |

On the U.S. side, we have to stop seeing ourselves as the political role model for the world; we must admit that we lack the knowledge to tell the Chinese how they should deal with the enormous complexities of their political development; and we cannot make our respecting the legitimacy of their government contingent on their accepting our ideas about how to reorganize it.

How can this process of mutual de-demonization be accomplished? Actually, it is already under way. It is based on that good chemistry between Chinese and U.S. culture mentioned above, which is accelerating with the ever-increasing traffic between our two nations. This traffic includes academic exchanges, but it also includes vital interactions between nonacademics, such as business people, members of the military, medical doctors, artists, and intellectually alert tourists. A good example is Admiral Joseph W. Prueher who, as U.S. ambassador to Beijing under President Clinton, won the respect of the Chinese while still forthrightly representing U.S. interests. An aviator, a warrior, and an administrator—not an academic—this man’s ability to analyze Chinese political realities was greater than that of many China scholars. Conversely, the traffic across the Pacific has brought us innumerable visitors and immigrants from the Chinese world whose great contributions to our society in many fields inevitably influence our image of their homeland.

Americans cannot continue to believe that the Chinese live with the fear on which totalitarianism depends when they meet one person after another in China who has no such fear—witness the 300,000 or so Taiwanese who have left their democratic society in Taiwan to live in Shanghai; the professor in a Shanghai university who publicly argues that Chinese laws lack moral legitimacy; and the professor at Peking University who says in the classroom that Mao’s revolution “replaced morality with ideology.”

On the Chinese side, developing a more favorable image of the rival power across the Pacific should be still easier because, as already mentioned, Chinese public opinion for more than a century has combined doubts about Western modernity with a basic desire to emulate it.

Leaders on both sides of the Pacific must build on these tendencies toward mutual appreciation to facilitate the cooperation both sides need to face urgent problems that are only too obvious.

Join the Conversation