August 2011

Magical Powers of the Color Red

By Billie Rubin, Hemoglobin’s Catabolic Cousin, reporting from the labs of Stanford Blood Center

Red, the color of blood, was once thought to have magical powers. Cro-Magnon man painted the sick and dead red, hoping to contain the life force. Early Egyptians painted their bodies with blood to ward off sickness. Later, pastes and dyes were substituted in the practice - a forerunner of makeup. In early England, red coverings were put on beds to treat smallpox, and strips of red cloth were used as cures for scarlet fever.

In many indigenous Australian Aboriginal peoples' traditions, red ochre, a color-producing earth pigment, is considered “Maban” (a magical material), and is applied to the bodies of dancers for ritual. In some secret ceremonies, actual blood is used as it is believed to attune the dancers to the invisible energetic realm of the Dreamtime, the belief that an individual’s soul exist before their life begins and continues to exist after death.

What else comes to mind for you as an association with the color red?

The Early History of Blood Transfusions

By Julie Ruel, Social Media Manager, Stanford Blood Center

Medicine and murder were two words I did not expect to see together in the title of an NPR talk on the history of blood transfusions. Holly Tucker, a professor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, was going about her usual business as she researched information for a class lecture on the discovery of blood circulation by an English physician in the 1620s. What she uncovered, purely by accident, led to her book about the history of blood transfusions, "Blood Work: A Tale of Medicine and Murder in the Scientific Revolution”.

The first blood transfusions on record took place in France during the 17th century. Controversy unfolded when Jean-Baptiste Denis, a French physician who was not well respected in his profession, was desperate to make a name for himself. In light of the recent revolutionary discovery of blood circulation, the British felt there was more to be experimented with. They wondered, “What would happen if we transfused animal blood into humans?” After all, animals were seen as being more pure than humans. They didn’t cause trouble. They were peaceful as they stood around grazing in the fields. The British were close to performing the first experiment when Denis jumped in and stole their idea, along with all the credit for it. They were none-too-pleased with the egotistical physician.

He certainly wasn’t impressing his own people, either. Many of the noble French were traditional Catholics, unwilling to accept the idea of animal-to-human blood transfusions.

Despite the opposition, the physician was determined to draw attention to himself and carry out the controversial procedure. A young boy in town suffering from fevers was a good candidate for experiment #1. To treat the fevers, it seemed logical to use blood from the cool, calm sheep. Denis performed the procedure and lo and behold, the boy survived! (It’s unclear whether the boy’s fevers were actually cured. But based on what we know of medicine today, that would have been purely coincidental.)

Experiment #2, transfusing sheep’s blood into a man simply for experimental purposes, was also a success (meaning, the patient survived).

The subject of experiment #3 was a mental patient who often wandered the streets of Paris yelling at folks at random. Blood from the peaceful cow would surely help this man. Sadly, it didn’t. After the transfusion, the man died. Held accountable for the death, Denis was charged with murder. The ordeal resulted in the ban of human blood transfusions in France unless approved by the Paris Faculty of Medicine. Denis was ultimately cleared of the charges, but soon after ceased to practice medicine.

In closing, here’s a look at some early beliefs and practices around blood that are hard to imagine by today’s standards:

• Before discovering that blood circulates, it was believed that it burned up in the heart, as one of the four humours.

• The French believed blood transfusions could cause a change in species.

• Goose quills were used to puncture the veins during early transfusions.

• Mental illness was thought to be the result of overheated blood causing vapors that affected the brain.

Needless to say, we’ve made leaps and bounds in transfusion medicine since then!

Free Career Workshop: Giving Blood Works

By John Williams, Marketing Manager, Stanford Blood Center

In 2009, during the height of the recession, Stanford Blood Center ran a promotion in which blood donors who donated during a two-week period were invited back to a career networking workshop, resume clinic, and job fair. The event, called “Giving Blood Works,” was a hit with job-seekers and a win-win for the unemployed and the recipients of the life-saving blood products. And let’s not overlook the benefit to the employers. After all, we like to think that someone who is willing to donate blood to help save a life must be a good job candidate!

Unemployment continues to plague the Silicon Valley, so we have resurrected this program and will be offering a free workshop to those who donate and sign up at a Center location between September 1 and September 13. This time around, we have two networking experts from Career Generations, as well recruiters from VMWare, TIBCO, PAMF, Option 1, 4Info.com, and more. In addition, as some people will chose to retrain for a new career, we will have Foothill College on hand to discuss their career programs. The workshop will take place on Tuesday, September 13 at our Hillview Center.

Career counselor Lisa Stotlar believes that you must create your serendipity by being open to possibilities. Perhaps the act of giving blood to save a life might do just that. What better way to improve your morale, do a good act, and possibly find a job.

To make an appointment to donate blood and sign up for this event, please visit our website.

Tips and Tricks: Logging on to Your Donor Account

By Jennifer Sellen-Reczkowski, Marketing Communications Specialist, Stanford Blood Center

Click here to view this information in an online tutorial.

You’ve just donated blood and you’re wondering if that new all-bacon diet you started has affected your cholesterol level. As a Stanford Blood Center donor, you have access to our online tools, which make it easy to keep your wellness in check and stay on target with donation goals. Follow these steps to get started!

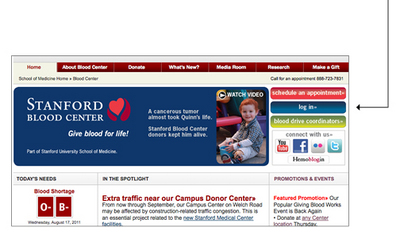

1. Visit our website. Navigate to bloodcenter.stanford.edu and click on the blue “log in” button at the top right of the screen.

2. Enter your donor ID number. This can be found on your donor ID card.

If you don’t have your donor ID number, send an email to sbconlinehelp@lists.stanford.edu or call us at 650-736-7786. We’ll ask you to confirm your date of birth so we can be sure to provide you with the correct ID number. We hope allow for custom usernames in the near future. Please stay tuned for updates.

3. Enter your password. Your default password is your birth date, entered as shown on the website, with slashes (example 01/01/1911).

If you would like to personalize your password, after you log in to your account, click the My Profile button, scroll to the password field and enter a new one.

4. Browse your account. Once logged in, you will be able to:

• view your blood type

• make an appointment

• check cholesterol test results and see vital statistics

• view previous donations

• manage existing appointments

• manage contact information, including address changes

• request an ID card be mailed to you

• shop in the loyalty store

We hope you’ll take advantage of these tools and find them rewarding. Of course the ultimate reward is the reminder that you’re saving lives whenever you donate!

Blood Collection in 1918

By Billie Rubin, Hemoglobin’s Catabolic Cousin, reporting from the labs of Stanford Blood Center

Towards the end of WWI, blood collection equipment consisted of a 1,000cc glass bottle with two perforated rubber stoppers. Glass tubing through each stopper was attached to rubber tubing, each with a needle at the end. One needle was for the donor, the other for the patient (probably one soldier to another), and suction was created with a syringe.

The equipment was sterilized in an autoclave or boiled in distilled water, and the needles were sterilized just before use in boiling liquid petrolatum (petroleum jelly or paraffin).

About 500cc of blood was collected in a glucose-citrate solution. Then by reversing the same syringe that was used to collect the blood, a pressure pump was created to infuse it. No testing was required. You just gave the patient 15 to 20cc of blood, waited 15 minutes and if he didn't react negatively, you would transfuse the rest. Hearing this really makes us appreciate current testing procedures and blood banking standards!

Donating Blood is Both High and Low Tech

By John Williams, Marketing Manager, Stanford Blood Center

It’s heartwarming when, in this time of technology-based connectivity, you see a family doing things together. In this case, Mary Sullivan and her sons Tom, Dan, Greg and Steve donated blood for the community as a family. Ironically, it was a technology-based promotion that drove this wonderful group into Stanford Blood Center that day.

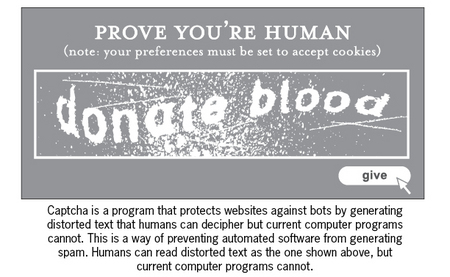

During a recent campaign, we encouraged donors to check in to one of our three Center locations on Foursquare or other location-based social networks, allowing them to share their whereabouts with their online community of friends. The Sullivan clan caught word of the promotion and donated blood together to earn the limited edition t-shirt, emblazoned with a graphic that replicates the “Captcha” box seen on many websites.

Creating promotions and programs that are relevant to our current and potential donors is paramount. For some folks, a phone call will always be the preferred manner of contact. For others, email works best. However, our recent expanded use of social media is proving to resonate with the high tech populace of Silicon Valley. To see an entire family respond to one of our new tech-savvy promotions tells us that we’re on the right track. Thank you Mary, Tom, Dan, Greg and Steve for participating in this new approach to such a fundamental activity – giving blood!

Just Another day at the Office

By Brooke Wilson, Communications Manager, Stanford Blood Center

You’re minding your business, going about your day, even doing something good for your health by popping into the gym for a workout—then suddenly a seizure sets in and you’re on the ground convulsing, foaming at the mouth, and unable to communicate. Not only has your day taken a dramatic turn—but your life may be in jeopardy. What happens next?

If you’re near a Stanford Blood Center blood drive, you’re in luck.

“We heard someone say that a man next door had fainted while working out,” said Robert Manio, R.N. Then, he and Charge Nurse Cat Layson, R.N., decided to investigate. Even though the person wasn’t a blood donor, they hoped they could help; Cat and Robert rushed to the nearby gym to assess the situation.

“The man was having a seizure when we arrived,” remembered Cat. “And we weren’t able to do mouth-to-mouth at that point.” They located the tools they needed (mouthpiece, defibrillator) and asked someone to call 911.

Then, the seizure stopped. But so did everything else—including his breathing and his heart. That’s when Cat and Robert used a defibrillator to deliver a controlled electric shock to the man’s heart. Then, a few seconds of CPR brought back his breathing and pulse.

“I’ve used defibrillators before, when I worked in a nursing home facility,” said Cat. “But that part was very stressful,” she said in reference to the time when the man wasn’t breathing. “I think I stopped breathing too, and once he finally took a breath, I did too.”

Cat and Robert then watched and maintained his vitals until the paramedics arrived with an ambulance to take the still-unconscious patient to a nearby emergency facility. “I was glad she [Cat] was there,” said Robert. “We work well together. But seeing this guy having a cardiac emergency really brought back memories for me; my father had a heart attack at the end of last year, and he passed away on January 1st.”

With humility and nobility, both Cat and Robert consider that day just like any other day of work at Stanford Blood Center. They seem shy about being called a “hero.” “I feel like this is expected of me,” explained Robert. “It’s part of my job.”

The Power of Two

By Isabel Stenzel, blood recipient and double lung transplant survivor

Hello Stanford Blood Center donors and friends! My name is Isabel Stenzel Byrnes and I'm a social worker and health educator, currently working for the Lucile Packard Pediatric Weight Control Program. I have a twin sister named Anabel, who is a genetic counselor at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital. We’d like to share our personal story with you in this blog.

Besides being our places of work, Stanford has special significance for both of us. We both graduated from Stanford University, I got married at Stanford, and actually Stanford Hospital saved both of our lives. Some of you may have even played a role in saving our lives.

Back in 1972, Ana and I were born with cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic lung disease that affects about 30,000 Americans. At birth, Ana had an intestinal blockage, and required emergency surgery. She received her first blood transfusion at three days of age. Some person out there allowed my twin sister to survive, and to join me in a lifetime of love, joy, and adventure.

CF is a very difficult disease. We developed chronic lung infections by the age of ten, and went in and out of the hospital for intravenous antibiotic “tune-ups.” By the time we were 18 years of age, we had been in the hospital cumulatively about 36 weeks of our lives, each. Also, we had to do respiratory treatments several times a day, every day of our lives, just to keep our airways clear. As twins, we developed a symbiotic relationship and helped each other with these treatments, allowing us to become independent from our parents and leave home for college.

Unfortunately, with each lung infection, our lungs became progressively damaged. One of the worst side effects of severe lung damage is hemoptysis, or the coughing up of blood. The day before my thirtieth birthday, I experienced a massive lung bleed and had a very real out-of-body experience. My dear husband had to witness what the ER staff said “looked like a trauma case.” I believe I coughed up nearly 3 cups of blood, and with limited lung capacity I went into shock and nearly died. I remember waking up on a ventilator in the ICU, and looking up to see bags of red blood dripping into me. I was amazed. Some part of someone else was infusing into me, and I was so grateful. It eased my immense fear, confusion and post-traumatic stress of what had just happened.

The next few months were the toughest times of my life. My lungs continued to bleed despite surgical procedures to block the pulmonary arteries. I was chronically anemic, and received several more transfusions. When one has low lung capacity, it is hard enough to breathe. When one is anemic, and not able to carry the oxygen properly in the blood, it is even more miserable. Each time I received blood, I remember feeling a surge of energy—like I had just been given a hit of caffeine! I felt SO much better—and again remember feeling so grateful for the good Samaritans out there who were helping me survive.

During my own struggles with CF, my sister’s story unfolded. Her lung capacity was always worse than mine. At 28, she had 20% of lung function remaining, and was dependent on an oxygen tank to breathe. She was emaciated and chronically fatigued. Despite tremendous fears, she decided to be listed for a double lung transplant. After 16 months on the waiting list, on June 14, 2000, a compassionate family who faced a tragedy said yes to organ donation, and my sister was saved. Her surgery was nine hours long. Because the CF lungs are so scarred, they adhere to the chest wall and removing them leads to massive amounts of bleeding. Ana received 30 units of blood during her surgery. She survived, and within 12 days, she went home to learn how to breathe again, walk again, and live again. Within 12 months, Ana was swimming, hiking, jogging, volunteering and working almost full-time. It was truly human resurrection--- all thanks to an organ donor and many blood donors.

Three years after Ana’s surgery, my health declined precipitously. I was in denial of how sick I was, so I had just gotten listed for a transplant. Suddenly, I could not breathe. Just brushing my teeth became an arduous task of suffocation. Within days, I was slipping away, with my carbon dioxide rising to dangerous levels that brought me close to a coma. My twin had to witness losing the closest soul mate of her life. I said my goodbyes to my husband and family, while in and out of consciousness. Days before I went into respiratory failure, I had a spiritual epiphany and kept telling people, “There’s going to be a miracle.” Within days, I coded and was placed on a ventilator. My family prayed for a miracle.

Less than 48 hours later, on February 6, 2004, my family heard five words that changed their lives forever: “We have lungs for Isabel.” Somewhere in Central California, a young man had become brain dead after a tragic car accident. He and I were both on ventilators in ICU together, with our families praying for a miracle at our bedsides. Somehow, fate chose him to go and me to stay. I will never understand why. But this young man had told his mother that if anything ever happened to him, he wanted to be an organ donor so he could help people… and his mother obliged.

My surgery was very difficult. My surgeon, the famous Dr. Bruce Reitz, who performed the first heart-lung transplant at Stanford in 1981, said I had less than 12 hours to live, and he had never performed surgery on anyone with a carbon dioxide level as high as mine (it was 140; normal is around 40). I bled profusely like my twin, due to the difficulty of removing my lungs, which literally breathed their last breath. I received 40 units of blood. Within two days, I woke up, thanked God, my doctors, and my lung and blood donors, and started to cherish each and every breath I was granted on this very borrowed time.

Fast forward several more years. After ecstatic days of swimming and winning medals at the US Transplant Games, jogging a half marathon, hiking Half Dome and writing a book together as healthy twins, Ana went into severe rejection. Only 50% of lung recipients survive five years, as lung transplants remain the least successful solid organ transplant. That’s because everything we inhale is potentially infectious, and each infection “wakes up” the immune system, starting the process of rejection. My sister’s rejection was merciless; within eight months she went from training for a marathon to being in a wheelchair dependent on oxygen. Thanks to God and Stanford doctors, Ana was offered a second transplant.

On July 13, 2007, Ana received the gifts of life again in the form of an anonymous organ donor and many blood donors. The second transplant was extremely tricky, as removing already transplanted lungs that have been stapled to the chest wall caused even more bleeding than CF lungs. It was touch and go, and the doctors fought for her life. When I saw Ana in the ICU, hours after her surgery, I was only allowed at the doorway of her room. Her blood pressure was dangerously low and the doctors were still working on her, trying to stabilize her vitals--- and give her more blood. Miraculously, just weeks later after a very tough recovery, Ana went home. We started to live again as healthy twins.

Our lives since then have been unimaginable. We make sure to be athletic to cherish the gift of health we’ve received. I’ve started to play the bagpipes to celebrate my lungs and allow the universe to hear my organ donor. My lung capacity is 125% of normal—something I couldn’t even dream of before my transplant. In 2007, Ana and I published a memoir, (The Power of Two, University of Missouri Press, 2007), and we have traveled all over the country speaking about cystic fibrosis and organ donation awareness. We have been graced with meeting our organ donor families to say THANK YOU. We returned to work, have witnessed the births of our nieces, are leaders in the CF and transplant communities, and have met countless friends along the way. My parents are so, so, so thankful to still have their twin daughters. And, in 2010, Ana got married, and I recently celebrated my 13th wedding anniversary with my loving husband. You see, when you donate blood and organs to save people, you don’t just save one patient. You save the entire family. I am saved because someone saved my twin. My twin is saved because someone saved me. And our entire communities are saved because we can still be here, contributing and trying to make a difference.

My illness was something I never wanted. Being public about it hasn't been easy. And coping with multiple losses including the high chance of dying young was something I wouldn't wish upon anyone. But, the gift of my illness is that it taught me to truly, truly live intentionally. And that kind of living has led to these remarkable opportunities. Today, Ana and I have no regrets. Ana and I are the luckiest people in the world.

I want to emphasize that NONE of these opportunities would have been possible without the selfless act of blood donors who went out of their way to help strangers. From the bottom of our hearts and lungs, we THANK THEM for giving us the gift of health. Together Ana and I received over 90 units of blood- probably from 90 different donors. In Japanese, the word for blood is ‘chi.’ Chi is also the word for energy. We received the living, breathing energy from 90 people and our lives now manifest that energy. We are living deliberately for our blood donors and for our organ donors. And our story is just one of millions that blood donors like you have touched.

Since 2009, Ana and I have been blessed to be involved in a documentary film, “The Power of Two,” inspired by our memoir. We never, ever imagined that our life experience with CF would unfold into these extraordinary opportunities! The film portrays the miracle of breath: something that never comes easy for anyone with cystic fibrosis or other lung diseases.

We wish you health more than anything. Right now, stop and take a slow, deep breath and feel your life force enter all the way to the depths of your lungs. May you truly feel our appreciation. May you be blessed with goodness as much as you have blessed others.

In gratitude,

Isabel Stenzel Byrnes

Please visit Isabel & Ana's website to learn more about the film. You can also watch the two-minute trailer here.

To sign up to be an organ donor, visit www.donatelife.net.