A recent article by SICHL members Sunil Puria and Anthony Ricci and members of the Stanford Otobiomechanics Group, Joris Soons and Charles Steele, Cytoarchitecture of the Mouse Organ of Corti from Base to Apex, Determined Using In Situ Two-Photon Imaging, appears on the cover of the Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology.

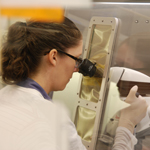

New techniques in imaging and genetic modification of mice allowed for the findings presented in this paper, which are a step towards a better understanding of how inner ear cells interact with each other and could lead to the development of computer models for the study of the mechanics of the inner ear.

We asked Sunil Puria and Joris Soons to describe this latest paper:

Sound vibrations from the external environment are collected by the eardrum, which then transmits them through the tiny bones of the middle ear to the fluid-filled inner ear where they vibrate a structure called the basilar membrane. Each of the frequency components comprising a complex sound such as speech or music excites the basilar membrane at a specific location along its length. These miniscule (on the order of a nanometer) displacements of the basilar membrane are then detected by some of the thousands of specialized hair cells embedded in the organ of Corti situated along this membrane, whereupon they are sent to the brain for interpretation.

Here we present, for the first time, detailed information about the three-dimensional organization and orientation of these hair cells and their surrounding supporting cells, which are factors thought to affect how the cells vibrate in response to sound, as well as information about how these structural factors vary along the length of the basilar membrane.

This structural information was obtained using an “mTmG” mouse variety, genetically engineered at Stanford, which features a red dye embedded in its cell membranes that makes the structures of the inner ear visible through an imaging technique called two-photon microscopy. This detailed information will help us to understand how the cells of the inner ear interact with each other, and in the near future will allow us to build computational models of the organ of Corti that we can use to test our hypotheses about cochlear mechanics in the mouse. This, in turn, will lead to a further unraveling of the complex mechanisms responsible for our remarkable sense of hearing.

Are all hair cells same or are they physicaly different according to their resonant frequency?

Thank you for your excellent question. Please see the answer from Dr. Ricci below:

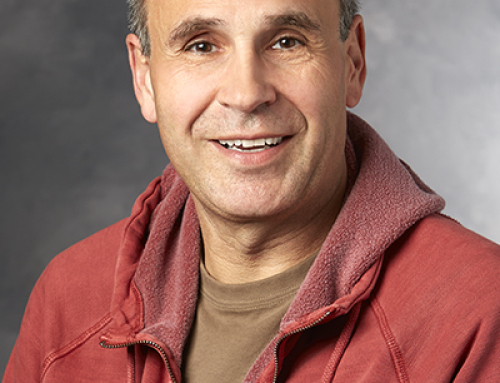

Good question and one we are trying to answer in more detail. Existing data suggests that hair cells, both inner and outer differ at multiple levels based on their frequency location. We know that the cells are morphologically different. We know that they are mechanically and electrically different and likely also synaptically different. We are presently trying to better define the molecular components responsible for these differences.

Thank you for answer!

Unfortunately it means that gene therapy will be much harder :(