Justia has made the full docket of legal filings in the Happy Birthday case available for free online at https://dockets.justia.com/docket/california/cacdce/2:2013cv04460/564772

Published on:

Published on:

How much of a photo do you need to alter to avoid copyright infringement? Hint: Cheshire Cat

Bloggers and artists often ask, “how much of a photo do you need to alter to avoid copyright infringement?” Five changes? Fifteen? The Seventh Circuit addressed the issue in the Kienitz v Sconnie Nation case recently. According to the court, Sconnie Nation made t-shirts displaying an image of Madison Wisconsin mayor Paul Soglin, using a photo posted on the City’s website that was authored by photographer Michael Kienitz.

The court looked to the Cariou v Prince decision, but complained that its approach to appropriation art looked only at whether a work is “transformative” and doesn’t fully address a copyright owner’s derivative rights under 17 U.S.C. Sect. 106(2). This court analyzes the market effect, looking to see if the contested use is a complement to the protected work (allowed) rather than a substitute for it (prohibited).

The photographer in this case did not claim that the t-shirt was a disruption to his own plans to license the photo for t-shirts or tank tops. He did not argue that demand for the original work was reduced.

And as for Fair Use factor three, the amount and substantiality of the portion used … the court wrote “Defendants removed so much of the original that, as with the Cheshire Cat, only the smile remains.” The original background is gone, its colors and shading are gone, the expression in the eyes can no longer be read, and the effect of the lighting is “almost extinguished.” “What is left, besides a hint of Soglin’s smile, is the outline of his face, which can’t be copyrighted.”

Published on:

IP Without IP? A Study of the Online Adult Entertainment Industry

Stanford Technology Law Review

Existing copyright policy is based largely on the utilitarian theory of incentivizing creative works. This Article looks at content production incentives in the online adult entertainment industry. A recent trend of industry-specific studies tries to better understand the relationship between intellectual property (IP) and creation incentives in practice. This Article makes a contribution to the literature by analyzing a major entertainment content industry where copyright protection has been considerably weakened in recent years. Because copyright infringement is widespread and prohibitively difficult to prevent, producers have been effectively unable to rely on the economic benefits that copyright is intended to provide.

Qualitative interviews with industry specialists and content producers support the hypothesis that copyright enforcement is not cost effective. As a result, many producers have developed alternative strategies to recoup their investment costs. Similar to the findings of other scholarly work on low-IP industries, this research finds a shift toward the production of experience goods. It also finds that some incentives to produce traditional content remain. The sustainability of providing convenience and experience goods while continuing content production relies partially on general, but also on industry-specific factors, such as consumer privacy preferences, consumption habits, low production costs, and high demand. While not all of these attributes translate to other industries, determining such factors and their limits brings us toward a better understanding of innovation mechanisms.

Published on:

Guidance on websites and copyright registration from the U.S. Copyright Office

As part of its new draft Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, Third Edition, we have guidance on registration for websites. The draft of the full compendium is over 1200 pages and covers publication, recordation, notice, deposits, along with other topics. Members of the public may make comments anytime before (or after) the Third Edition goes into effect on December 15, 2014. For more see http://copyright.gov/comp3/

Published on:

Is it in the Public Domain? Review by Peter Hirtle

[UPDATE from Peter Hirtle: That didn’t take long. The authors of the handbook have responded to my specific issues below by updating and/or correcting the handbook. A new version is available at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/FINAL_PublicDomain_Handbook_FINAL(1).pdf. A very good resource has become even better.]

Stanford Copyright and Fair Use Center Advisory Board Member Peter Hirtle reviews Is it in the Public Domain?

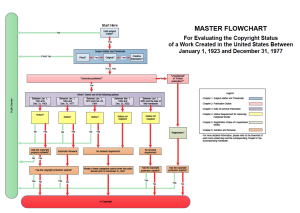

It is very difficult to determine whether works are in the public domain in the United States. That is why I had to create my duration chart as an aide–mémoire: any time I tried to remember the various options, I got them wrong. It is also why I felt compelled to write an article highlighting some of the traps lurking within the seeming clear-cut categories. And it is why Stephen Fishman needs 700+ pages in his legal treatise, Copyright and The Public Domain. Continue reading →

Published on:

Public Domain Handbook – Samuelson clinic

The Samuelson clinic has put together what looks like a useful, thorough new handbook to help you determine if a work is in the public domain. http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/Final_PublicDomain_Handbook.pdf

Most helpful is the complete FLOW CHART. We’ll put both the handbook and the flowchart in our CHARTS AND TOOLS section for your hand reference. http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/Final_PublicDomain_Flowcharts(6).pdf

Published on:

Future proofing copyright

The flawed copyright system has an impact on creative economy. Copyright’s influence on digital opportunities in the UK’s creative economy provided impetus for broad scale initiatives for improvement. Audience expectations have changed dramatically. #mediaxfocpod

mediaX connects businesses with Stanford University’s world-renowned faculty to study new ways for people and technology to intersect.

Published on:

Who’s the Owner: A White Paper on “Improving Copyright Information Management: An Investigation of Options and Areas for Further Research”

The U.S. Copyright Office came to Stanford Law School yesterday to conduct a roundtable on Recordation Reengineering, The Stanford Law School Law and Policy Lab submitted comments and a thoughtful White Paper, and live tweeted the proceeding along with us (see @slspolicylab and @fairlyused). The Law and Policy Lab was represented at the roundtable by Peter Holm, third year law student. We interviewed Peter to get the essence of the issue and the White Paper, which is available as document 23 on the Copyright Office comments page.

The roundtable was conducted by Robert Brauneis, Abraham L. Kaminstein Scholar in Residence, U.S. Copyright Office.

The White Paper was submitted to Brauneis by Ariel Green, Sean Harb, Peter Holm, Kingdar Prussien, Kasonni Scales, and Juliana Yee, Copyright Policy Lab Practicum

Mary Minow: What was the impetus that led Stanford to research and write this White Paper?

Peter Holm: The Copyright Office contacted Stanford initially and Professor Paul Goldstein contacted us. I took a copyright class in the Fall of 2012 with Professor Goldstein. He emailed a few of us over the summer to see if we were interested. He described it as a chance to offer concrete suggestions to modernize the Copyright Office operations.

Minow: That sounds broad. When did the focus narrow to copyright document recordations?

Holm: That narrower focus developed in the Fall as we spoke with Maria Pallante, Register of Copyrights; Jacqueline Charlesworth, General Counsel, United States Copyright Office, and then with Professor Bob Brauneis who is there as a scholar in residence on these issues.

Minow: Why does this matter?

Holm: To have economic value, an owner of copyrighted works has to be able to sell and make his works available. If you don’t know who the owner is, you can’t make those transactions and the works lose value, so availability of this information is integral.

Minow: How do people find out now about who owns what copyrights?

Holm: It varies by industry. Neither registration of copyrights nor recordation of copyright transfers are required, but both have benefits to the owner. Because taking these steps is voluntary, the amount of information available for any given work varies considerably. So for example, in the music industry, there is extensive ownership information and licensing availability through ASCAP, BMI and the Harry Fox agency. So if I want to play Elton John at a party open to all Stanford students, I can get a license from those collecting societies and not worry about who owns the rights.

Whereas if I find a book in the library, published in 1955 and I want to use it, it’s harder to find information. There are probably records at the Copyright Office for the initial owner, as registration used to be required, but subsequent transfers might not have been recorded, so many questions remain. Did he transfer the copyright at some point? If not, is the author still alive? Did it go to his heirs, and who are they?

There is a substantial cost to investigating this, and often one doesn’t know who to talk to.

Minow: What’s the gist of your proposal?

Holm: It’s not a proposal per se. It’s really a list of options and tradeoffs. We look at the role of the copyright office. Should it hold a giant database, partner with third parties? Really it comes down to how do we best provide access to the public and get the information they need without overly burdening authors with unnecessary requirements? We don’t want to make it too hard for them to exercise their rights to transfer works, since transfers are potentially beneficial.

Minow: What are the benefits of recording transfer documents, since it’s not required?

Holm: It gives constructive notice of the transfer. Also, if you record a transfer document there is a presumption of validity for that document over subsequent instruments of transfer of the same title.

Minow: Thanks for talking with us today.

——

Peter Holm is a third year law student at Stanford Law School.

Mary Minow is the Executive Editor of the Stanford Copyright & Fair Use page.

Published on:

Deadline: April 14th. Public invited to weigh in on orphan works – US Copyright Office

ORPHAN WORKS is red hot again. After a number of failed legislative attempts and a couple of high profile court cases, its back to the drawing board, albeit a better defined drawing board. On the one hand, most everyone agrees that for true orphans, it would be great for us all to be able to digitize, copy, adapt, distribute and otherwise use them. On the other hand, how do we know it’s a true orphan? What if there is an “orphan” owner?

The Copyright Office just held two days of public roundtables on Orphan Works (See twitter #orphanworks for some flavor of the sessions). The Copyright Office has now opened up the floodgates for public comment from those of us who were not in D.C. Continue reading →