Quake-Catcher Network seeks volunteers on campus to host seismic sensors

Stanford Earthquake researcher Jesse Lawrence wants to plug in small seismic sensors into USB ports on computers across the campus. The sensors, which periodically send a report to the researcher’s computers, will provide valuable data on how buildings respond to earthquakes.

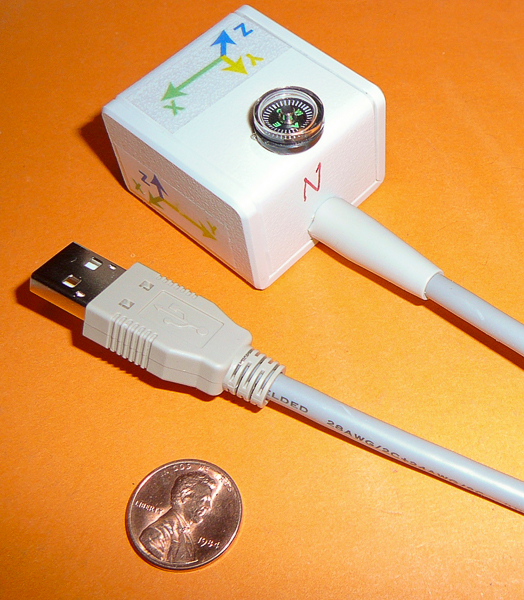

If you can spare a little space on your office wall about the size of a small Post-it Note, you may be able to host a tiny seismic sensor that will help the researchers of the Quake-Catcher Network delve deeper into the subterranean world of earthquakes.

The group wants to create a dense network of more than 100 sensors in buildings across the campus to study how the energy that earthquakes generate travels through the subsurface geologic structure, when the seismic energy focuses on particular buildings and when it doesn’t, and how different types of buildings behave when they are shaking during an earthquake.

There are a few basic requirements for a volunteer’s computer, such as being less than about five years old, running either a Windows or Macintosh operating system and having a spare USB port to which the sensor can be hooked up. The computer also has to have an Internet connection so the sensor data can periodically be sent to the project’s server. But in terms of where your computer is located, the researchers are pretty flexible.

"For a lot of this, we prefer the sensors to be in fairly quiet locations," said Jesse Lawrence, assistant professor of geophysics and a principal investigator on the project. "But if you have a noisy location, that is also interesting to us. We want a whole variety of data. We’d like to find out what we can do with noisy data."

By understanding how a building responds to ambient day-to-day sources of shaking such as elevators going up and down, doors slamming, ventilation systems pumping, and cars and trucks rolling by, the researchers will be better able to predict how the building might respond to more severe shaking during an earthquake. Having the routine data will also let them clean up the signals recorded during a seismic event, enabling them to do a more precise analysis of how the energy moved through the subsurface and affected the buildings.

In addition to building a network across the campus, the researchers also want to put large numbers of sensors in individual buildings, Lawrence said.

"There are a lot of instruments in buildings, but very few instrumented buildings are instrumented well," he said. For example, he said, the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco has only about three sensors spread throughout its 48 floors.

"One of the things that we would like to do is investigate buildings like Hoover Tower," he said. "We are going to measure every floor of Hoover Tower and get the vibrations."

Lawrence said that while the researchers want to put sensors on the ground floors and basements of buildings, because shaking in those locations will be more representative of the actual ground motions, they are also interested in recording motion on higher floors. And they are interested in putting sensors on both exterior and interior walls on the same floor, including temporary or non-weight-bearing walls, to see how motion varies within a building, which he said has not been investigated much up to now.

Volunteers do not have to commit to hosting a sensor for a set length of time.

"We are interested in putting the sensors out for any sort of duration, from a couple weeks to a couple years," Lawrence said. "A couple weeks provide a good ambient noise data set and a couple years will allow us to record some of the intermediate earthquakes, or a large earthquake if one happens. And we could actually see how well did we do at our predictions."

Installing a sensor only takes a few minutes, requiring just a quick dab of rubber cement to attach the sensor to a wall and downloading some software, according to Lawrence, who said the sensors can be easily removed.

The network operates on the same principles as other distributed computing projects such as Stanford’s folding@home project, in which people are donating computer time to a study of how proteins fold by having the sensor program running in the background, using only a small amount of the computer’s processing power to record vibrations and occasionally transmit the data to the project’s server here on campus.

If you are interested in joining the Quake-Catcher Network, you can visit the project’s home page for further information.

Share This Story