Three authors encourage Stanford freshmen to 'keep hoping and dreaming and fighting'

"Three Books" program brings authors Abraham Verghese, Lan Samantha Chang and Malcolm Gladwell together to discuss outsiders, outliers and what we mean by "success."

Three acclaimed authors guided Stanford's incoming freshmen in a moving, provocative and often inspirational discussion that focused on outsiders, outliers and what we really mean by "success."

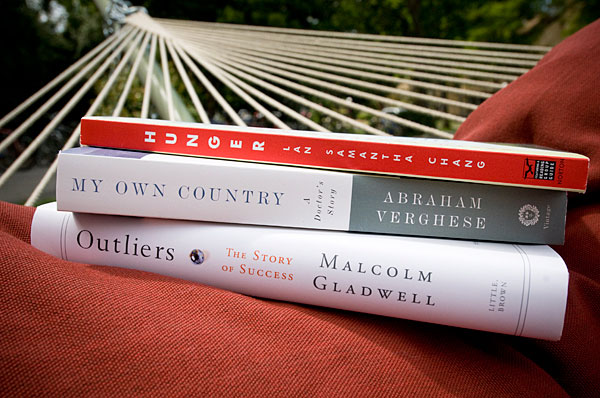

The event was this year's "Three Books" program for the entire freshmen class, held in a packed Memorial Auditorium on the evening of Sept. 16. Stanford mailed the books – Lan Samantha Chang's Hunger, Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers: The Story of Success and Abraham Verghese's My Own Country – to the students earlier this summer.

Two of the authors have strong Stanford ties: Verghese, a specialist in infectious diseases, is a professor of medicine at Stanford; Chang, director of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, is a former Stegner Fellow. The third, Gladwell, is a writer for the New Yorker.

The trio was selected by the husband-and-wife faculty duo who moderated the discussion: Professors Harry and Michele Elam. He is senior associate vice provost for undergraduate education; she is director of the Program in African and African American Studies.

Michele Elam, an English professor, noted that all three authors wrote books that seemed to "explode usual discourses about identity, politics, race."

The authors question "the arbitrary conditions for success" and ask, "What social legacies are powerfully impacting my life? Not 'What will be my profession?' but 'What is meaningful work?'"

Gladwell's book describes the context of genius and argues that genius does not rely solely on individual talent, ambition or hard work – it relies on factors within the community and society as a whole. Chang's collection of stories, mainly describing the experiences of Chinese immigrants to America, shows the consequences of acknowledging memories. Verghese's account describes his work at a Veterans Affairs Hospital in Johnson City, Tenn., working with the AIDS epidemic and its impact on rural communities.

Outsider looking in

Verghese, who grew up in Ethiopia although his family is Indian, said he never heard the word "expatriate" until civil war broke out in the 1970s and his family immigrated to America. As a writer, he said he feels he is "very much an outsider looking in" – a feeling he suspected was shared by many in the audience.

"It's not a bad thing. It doesn't make you lesser," he reassured the students.

Both Chang and Verghese discussed the pressure from immigrant parents to become, as Verghese put it, "a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer or a failure."

"My parents wanted me to be a doctor," said Chang. "They wanted me to be safe in this country. However, I was like an ox moving in another direction." She wrote "doctor" as her destiny in her college application, and later deferred her entrance into the law school that admitted her. She even had a stint in public policy school. "There's no straight-shot path for many people to find out what they really want to do," she said.

Verghese also headed toward his parents' expectations – but crashed on the shoals of mathematics. He was inspired instead by the protagonist of W. Somerset Maugham's Of Human Bondage. "Not everybody could be an artist or a math genius," he concluded, "but anyone with an interest in fellow human beings … could be a great doctor."

At the beginning of his medical career, he said, "I had the conceit of cure" – a luxury not available to, say, oncologists. It was ironic and fitting that "a fatal illness should fall in the lap of people like me."

Treating AIDS patients, however, taught him "the difference between healing and curing." He described the effect of the disease in terms of "the physical sense of something lost, a great sense of violation."

"There was so much one could do about the sense of spiritual violation," he said. His visits with families brought about a healing of sorts. "I was doing nothing but just being there," he said, but, referring to the Stanford freshmen, added, "If you asked me when I was their age, I would never have defined that as success."

Some of the idealistic freshmen, interested in making a more equitable society, wondered how to change Gladwell's dynamics for the poor and less advantaged.

Gladwell said it was important to "remember when we talk about opportunities and advantages, we're not just talking about wealth and position."

The British-born Canadian son of an English mathematician and civil engineering professor and a Jamaican-born psychotherapist who is the descendent of African slaves, Gladwell pointed out that he came from "a long line of people who valued education." His mother came from a family that "felt that their daughters could go on and do whatever they wished."

"It's possible to be hugely advantaged without having money in your pocket," he said.

Determinants of success

Invited to debate Gladwell about the effect of collective versus individual determinants of success, Chang declined but emphasized "the power of narrative and individual stories. Those narratives can be more powerful than numbers."

Although she also came from a family that had, and valued, education, she noted of her three sisters, "Our lives have been quite different. Some of us were more adventurous than others, some have gone farther in our profession than others.

"There's something to be said for self-determination. It's possible to tell a different story about yourself – not the one others tell about you. You can compose your own story. You have your own ability to choose who you are." Rather than contradicting Gladwell's view, she said they were studying the same questions from different angles.

Gladwell's conversation often turned to how collective influences can be manipulated to boost individual potential. Although we cannot easily replicate the effects and privileges wealthy families can pass on to their children, he said, "Maybe we can do a better job.

"Do we give everyone the same chance to fulfill potential? That is a much harder task of democracy."

Student Garry Mitchell from the Ujamaa theme house asked how one moves forward without leaving behind important aspects of their own culture – and how to face those who criticize students for assimilating too much or not enough.

Verghese said that Yeats' "perfection of the life," as opposed to "perfection of the work," includes family roots and the culture we come from. Rather than facing a "choice," we must "negotiate those two paths."

One student asked Chang if she thought the encouragement to follow dreams risks "setting us up for punishment."

"I do. I do. I do," Chang answered emphatically, but nevertheless added, "You should go ahead and keep having extravagant dreams. Keep hoping and dreaming and fighting."

Media Contact

Cynthia Haven, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-6184, cynthia.haven@stanford.edu

Share This Story