Stanford archive shows origins of Martin Luther King's 1963 'I have a dream' speech

Stanford's MLK Institute archive shows how the civil rights leader worked and reworked material for the famous speech that turns 48 this Sunday.

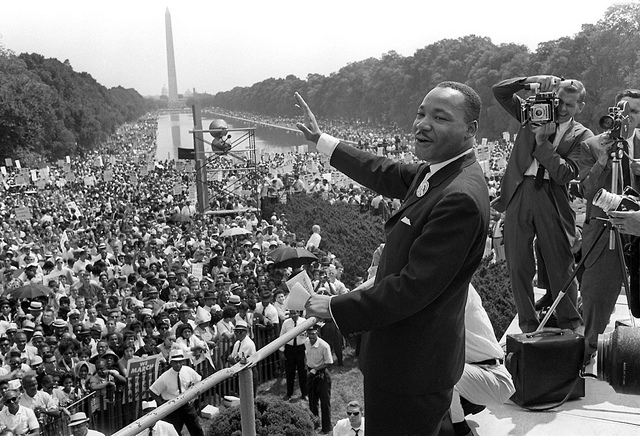

At a watershed moment in the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. called to a roaring crowd: "I have a dream!"

He then described his dream for equality and justice, his voice rising to a rousing conclusion: "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!"

That's King's famous "I have a dream" speech to 200,000 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, right?

Not quite. King spoke these words at the Freedom Rally in Detroit's Cobo Hall several months before the famous Aug. 28 speech that turns 48 on Sunday, as the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial is dedicated on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (Note: Due to weather, the dedication of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial has been postponed.)

"I think one of the misconceptions people have about King was that all of his material was spontaneous and did not repeat," said Stacey Zwald-Costello, assistant editor at the King Papers Project at Stanford University's Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

"However, the opposite is true – he spent a lot of time preparing his speeches and often recycled material, using it in different places and ways in order to get his point across."

The Cobo Hall speech is one of the more notable antecedents of the famous speech. It will be included in Vol. 8 of Stanford's projected 14-volume edition of King's most significant correspondence, sermons, speeches, published writings and unpublished manuscripts.

The speech, and his particular way of speech-making, must be understood in the context of his life, said Zwald-Costello. "His schedule was insane," she said. "He was giving talks two or three times a day."

Hearken back to an era before Google, YouTube and the 24/7 news cycle. King was traveling across the country, speaking constantly, in an era when he couldn't count on his words being broadcast on television, let alone the Internet. He had to say the same thing again and again to get his message across.

Although King was a very practiced, fourth-generation preacher, said Zwald-Costello, "he had a team with him. There were definitely people who were helping him write speeches, or coming up with ideas for speeches."

In the spring of 1963, he had spearheaded the Birmingham campaign of protests and was jailed in April. "It was a pinnacle for the nonviolent movement," said Zwald-Costello.

"This is really one of the last years for King's nonviolent direct action," she said. The civil rights movement was "going toward greater division and people more reluctant to participate in nonviolent direct action." The Black Power movement also was on the rise.

The famous speech has other antecedents besides Cobo Hall: King began giving speeches referring directly to the American dream in 1960, and gave versions of his dream speech throughout 1961 and 1962.

Those close to him, including the prominent gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who shared the stage with him that August day of the March on Washington, would have been familiar with his "dream." According to legend, as he delivered his speech, she shouted, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!"

So he winged it: "I have a dream … that the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood … that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." He mentioned the dream nine times.

King's version of the day was different. As he said later: "I started reading out that speech, and I read it down to a point. … And all of a sudden this thing came to me that … I used many times before … 'I have a dream.'

"I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn't come back to it."

King was named Time magazine's 1963 Man of the Year. In 1964, the 35-year-old Baptist preacher was the youngest man to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. The speech has been hailed as one of the greatest of the 20th century.

Media Contact

Stacey Zwald-Costello, MLK Institute: (650) 725-8829, szwald@stanford.edu

Cynthia Haven, Stanford News Service: (650) 724-6184, cynthia.haven@stanford.edu

Share This Story