A father knows best: Vint Cerf re-thinks the Internet in Stanford talk

He helped develop the Internet in the 1970s while at Stanford. Now, Vint Cerf is thinking about how to improve his creation that's become the greatest communication force of our time.

To most, a wine cellar is just a cool place to keep some vintage vino. For Vint Cerf, the revered former Stanford engineering professor and graduate of the university, it is a portal into the future. His wine cellar is networked. Cerf can monitor and control the temperature, humidity and other important information from his smartphone.

Welcome to the "Internet of things," a much-discussed vision of a tomorrow in which virtually every electronic device – ovens, stereos, toasters, wine cellars – will be networked.

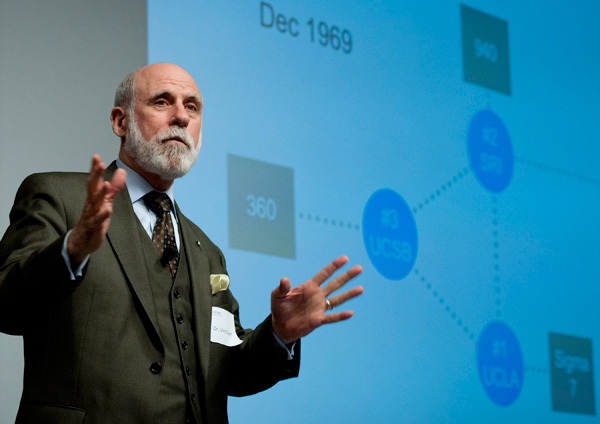

Improving Internet security requires a delicate balance between freedom and control, Vint Cerf told the audience at Stanford Engineering's 'Heroes' Day.'

Cerf, who is now vice president and chief Internet evangelist at Google, laid out that vision as the guest of honor at Stanford Engineering's first "Heroes' Day." The former professor's lone request on his day of honor was to be with students. His topic: re-thinking the Internet.

And when one of the so-called "Fathers of the Internet" says we need to re-think his baby, people listen. Cerf addressed a standing-room crowd in the NVIDIA Auditorium at Stanford's Jen-Hsun Huang Engineering Center on Tuesday. Hundreds more tuned in via live webcast.

As Cerf held forth, those in the house and online would discover that re-thinking the Internet will take a lot of thinking.

Rules of the road

Back in the mid-1970s, when Cerf was a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Stanford, he and a partner at the Department of Defense, Bob Kahn, were assigned to create a system of data transfer between computers that could withstand the sort of Cold War imaginings that dominated the day. They essentially had to make sure that if the world came to an end, data would get through.

What the pair came up with was the basic architecture of the Internet and TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol), the "rules of the road" that govern how all those ones and zeroes get addressed, subdivided, sent packing and somehow arrive where they are supposed be and get put back together as they should.

It was a divide-and-conquer, redundant-path model that turned the Internet into an unstoppable force and made it virtually impossible to bring the system down.

Why, then, does Cerf think we must re-think his handiwork, the greatest communication force of our time?

"The Internet was just not designed for the way we use it today," he said. "In the 1970s, we were only trying to link a few sites together – a few universities, a couple military bases. We had no way to anticipate billions of personal computers, much less smartphones that are far smarter and infinitely more mobile than the classroom-size computers of the time."

First off, the naming system developed by Cerf and Kahn – known as IP addressing – is proving inadequate. Their system allowed for about a billion IP addresses. With personal computers and smartphones becoming more ubiquitous, the world will need billions of IP addresses.

We have simply run out of ways to address all our machines, Cerf said.

And there are more machines coming if the Internet of things comes to fruition.

A looming cloud

Security, however, is the real looming cloud, Cerf said. The defense mechanism to date has been to circle the wagons by creating firewalls to protect us from attack by outside forces. But firewalls are leaky and prone to attack from within by viruses, malware, spyware and worse. We are left with billions of devices vulnerable to attack.

But improving security requires a delicate balance between freedom and control, Cerf said. He was careful to delineate that our need for stronger authentication should not limit online anonymity. The fact that the Internet allows people to gather and publish information with the option to remain anonymous has been a driving force behind the Internet, Cerf said.

The hard, hard problems

These technical issues do not even begin to get at the monumental policy issues facing a new Internet that must work across borders and political realities.

"As we are seeing in China and Egypt and elsewhere, the Internet is an undeniable social force," Cerf said. "This is a threat to some. Yes, the Internet is free and open today, but there are no guarantees. It might not always be so."

Such complex policy issues will no doubt need to be resolved.

"These are hard, hard problems and we haven't even talked about the commercial questions – who gets to make money and how are they going to make it," he asked, hinting at the vastness of the task ahead.

Innovation and revolution

Our reward for re-thinking the Internet is that there is room not only for innovation but for revolution.

"The way things are today doesn't always have to be so," Cerf said. "We can imagine a better Internet and we can make it happen."

This Internet of things, for instance, could help us meet the challenges of energy efficiency through improved production and storage of electricity, and smarter power management could greatly smooth the peak-and-valley pattern of energy production and demand.

A nod to Stanford

Looking back at his life and his invitation to join the faculty at Stanford, Cerf was humble.

"I turned them down," he said. "I didn't think I was smart enough to be teaching such smart students. But when the people who wrote the textbooks I was learning from, Don Knuth and others, kept calling, I couldn't say no. Stanford was great for two reasons: freedom and very, very smart students. I always knew I had a smart kid sitting in front of me helping me out."

And he waxed philosophical when talking about his latest project – an often misunderstood undertaking he calls the "Interplanetary Internet."

"Some people don't want me to talk about the Interplanetary Internet," he said. "They think I've gone off the deep end, but we're not talking about communicating with aliens here. I wouldn't even know how to do that, but if we are to someday travel across the vast distances of the galaxy, we will need to learn how to communicate over long stretches of space and time."

As he tells it, the Interplanetary Internet is just one more extension of his life's work. "It's about ensuring that our messages make it to their intended audiences, that they are intelligible, and that they are whole when they get there."

These are the lessons Vint Cerf has learned best of all.

Andrew Myers is associate director of communications in the School of Engineering.

Media Contact

Andrew Myers, Stanford School of Engineering: (650) 736-2245, andrew.myers@stanford.edu

Share This Story