'Microfluidic' chips may accelerate biomedical research

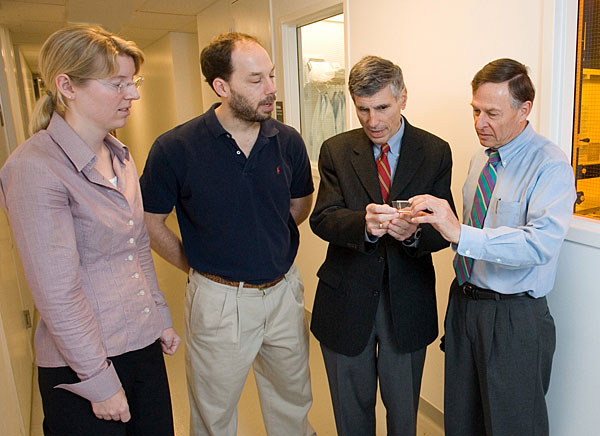

From left: Foundry Director Jessica Melin, bioengineering Professor Stephen Quake, Medical School Dean Phil Pizzo and School of Engineering Dean Jim Plummer examine a microfluidic chip outside the Stanford Microfluidics Foundry at the facility’s opening Jan. 11 at the Clark Center.

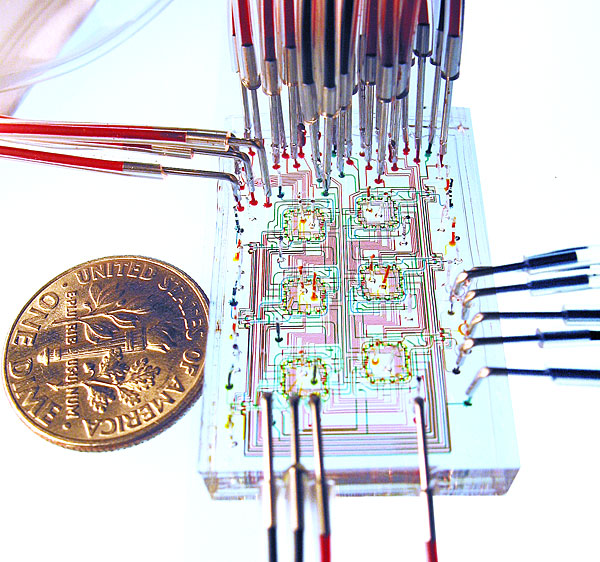

This microfluidic chip houses bioreactors, where bacteria can be cultured and observed. Stanford researchers make the chips using optical lithography to etch the circuit pattern into silicon. The etched silicon acts as a mold. Silicone is poured into the mold and then removed. By stacking several layers of molded silicone and then encasing them in glass, researchers can create an integrated circuit of channels, valves and chambers for chemicals and cells—like a rubbery labyrinth.

Silicon microelectronics have made computation ever faster, cheaper, more accessible and more powerful. Microfluidic chips, feats of miniscule plumbing where more than a hundred cell cultures or other experiments can take place in a rubbery silicone integrated circuit the size of a quarter, could bring a similar revolution of automation to biological and medical research, says Stanford bioengineering Professor Stephen Quake. To put the university on the leading edge of that movement, on Jan. 11 in the James H. Clark Center, Quake opened the Stanford Microfluidics Foundry to manufacture custom "labs on a chip" for academic researchers.

"Right now biological automation is in its infancy," Quake says. "It's all about using large robots to push fluids around in the same way that computers in the early days were about big mainframes. It's expensive, it's inflexible and it hasn't really trickled down to the academic research level yet."

The expense, inefficiency and high maintenance and space requirements of robotic automation systems present barriers to performing experiments. By contrast, microfluidic chips are inexpensive and require little maintenance or space. They also need very small amounts of samples and chemical inputs to make experiments work, making them more efficient and potentially cheaper to use.

Quake likens the advent of microfluidic chips to the rise of the personal computer because they both make automation more accessible. "Chip-based automation is going to make it much more enabling for individual researchers," Quake predicts.

Fundamental experiments fasterResearchers can use the chips to carry out some of the most fundamental and important experiments in biomedical research, Quake says. One cell-culture chip recently designed in Quake's lab by postdoctoral researcher Rafael Gomez-Sjoberg and visiting scholar Anne Leyrat, for example, has 100 chambers to hold individual cells and all the microscopic plumbing necessary to add any combination of 16 different chemical inputs to those chambers. Researchers could use the chip to test how different inputs might cause stem cells to transform into more specific cells needed for particular treatments. The chip could also be used to test how different combinations of antibiotics affect a particular bacterium.

A different microfluidic chip designed by Quake's former student Carl Hansen has shown great results in preparing highly valuable and expensive purified proteins for structural analysis. Scientists now must crystallize proteins before their examination with X-rays. This tedious trial-and-error process is greatly speeded using microfluidic chips compared to traditional methods, Quake and colleagues have shown.

A resource for academiaThe foundry, headed by Quake and directed by research associate Jessica Melin, will be a resource on campus and beyond for making custom microfluidic chips for academic researchers who commission them, and for teaching researchers and students how to make their own if they desire, Quake says. Quake and Melin plan to teach classes on microfluidics and chip making in the foundry every quarter beginning with the current one. The foundry employs four technicians and was funded by the schools of Medicine and Engineering and the university.

Quake helped found a Bay Area company called Fluidigm that serves commercial clients. In contrast, the Stanford foundry will help fulfill small orders of chips to his academic colleagues for specialized research applications.

"It's a way to get this technology into people's hands," he says. "I'd like for everyone in the Medical School and in the life sciences here at Stanford to think about how to use this kind of fluidic automation in their own research and to think about cases where it will help." The chips might just become even more important to some researchers than their computers.

David Orenstein is the communications and public relations manager at the Stanford School of Engineering.

Share This Story