Roy DeCarava, 1919–2009

November 12, 2009

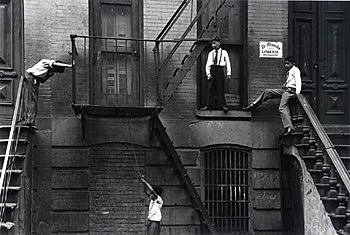

Roy DeCarava's Lingerie, New York

Roy DeCarava, an American master, died October 27, 2009, a few weeks shy of his ninetieth birthday. Born in Harlem in 1919, and coming to adulthood during the Harlem Renaissance, DeCarava became a photographer of the street and the people who inhabited that day-to-day world. He was good friends with the poet Langston Hughes, and together they collaborated on a book titled The Sweet Flypaper of Life. Unlike the prints of other photographers who kept their distance, DeCarava's are marked by a warmth that connects the viewer to the subject. They often feel like jazz without sound.

"Roy DeCarava stands as one of the most important American photographers of the twentieth century in part because he took the form of social documentary photography and made it subjective and lyrical," Merry A. Foresta told me as director of the Smithsonian Photography Initiative. "As one of the first African American photographers of the modern era, DeCarava depicted black life with an intimacy and sweetness that was unprecedented," she added.

There are nearly a dozen examples of DeCarava's work in American Art's collection. Couple Dancing, New York (1956) portrays a sensual moment, barely lit, private, yet the viewer is allowed to watch. In Lingerie, New York (1950) young children hang out on the stairs and fire escape of what appears to be a shuttered brownstone, the site of the shop La Blanche Lingerie. We are immediately drawn to the boy in tie and suspenders balancing on the window ledge, as if it were the most natural thing in the world--caught perhaps in that sticky, sweet flypaper known as life.

Related post on DeCarava from the Smithsonian's Photography Initiative blog, The Bigger Picture.

Posted by Howard on November 12, 2009 in American Art Everywhere, American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (0)

Picture This: Playing Punball

November 9, 2009

A museum visitor plays William T. Wiley's Punball: Only One Earth.

You've seen the William T. Wiley exhibition. Now play the game! What, you haven't seen the show yet? Well, now's your opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. On Thursday, November 12, from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m., visitors will have a rare opportunity to play Wiley's Punball: Only One Earth, which includes his distinctive imagery. He based his punball machine on a 1964 pinball game called "North Star." Please note that playing time is limited to five minutes per person on a first-come, first-serve basis. But take your time perusing the rest of the show.

What's It All Mean: William T. Wiley in Retrospect runs through January 24, 2010.

Posted by Jeff on November 9, 2009 in American Art Here, Picture This

Permalink

| Comments (0)

Picture This: Albert Paley's Portal Gates

November 6, 2009

Left: the museum's David DeAnna, contract art handler Jorge Herrera, and Justin Chambers move the right gate into place. Right: Herrera, DeAnna, and Jerry Hovanec finish the installation.

Our exhibitions' team was up and at ‘em early on October 27 to unpack and reinstall sculptor Albert Paley’s Portal Gates at the museum's Renwick Gallery. For the past two years, the beloved pieces were off-site as part of Albert Paley: Portals & Gates, an exhibition organized by the University Museums, Iowa State University. Commissioned by the Renwick Gallery in 1974 to adorn the entrance to the gallery's shop, where they stood for many years, the Portal Gates marked a turning point in the young goldsmith's career. I don’t think I'm exaggerating to say that this masterpiece of ironsmithing was greatly missed!

On the left, the museum’s art handlers use a winch, or mechanical lift, to hoist the 1,200-pound gates, made of forged steel, brass, copper, and bronze. On the right, they carefully place the gates in an alcove built by our own Jim Baxter. The process took several hours, since the handlers had to be meticulous, so as not to damage the pieces or the floor, the walls, and themselves! We at the Smithsonian American Art Museum are happy to present the gates once more to the public and hope that you’ll stop to see them soon!

Posted by Mandy on November 6, 2009 in American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (1)

Dave Hickey and the State of the Arts

November 4, 2009

"My ten millionth grandfather was Jonathan Edwards," critic Dave Hickey told us last week as part of the Clarice Smith Distinguished Lecture Series at American Art. He added, "But I'm not going to give you any of that." What he did give us, instead, was a thought-provoking hour on the nature of contemporary art in America and how ideals of art and the artist in society were shaped centuries ago. From the Roman Republic to the Florentine Renaissance to the downtown New York art world that emerged after World War II, Hickey riffed on the themes of paganism, materialism, commerce, success, and mediocrity.

Hickey is upset and concerned that in American democracy the average becomes the paradigm, and he used the example of an everyman fiddling with his iPhone in the mall. Institutions in America such as museums, foundations, and the government all level things off because what they know is how to make a democracy. "Americans can make great art, literature, and music, but American institutions cannot help at all in this," said Hickey. The majority has never created exceptional art. It has always been the minority "working in the backwash of his own work" that creates great art. Hickey even called in James Madison for backup and quoted the founding father as saying, "Genius is an accident, mediocrity is a fact."

The art world in America was formed by people who did not create a celebration of America but a refuge from it. What people created in those downtown lofts was a victory over rectitude. If you look at Jackson Pollock, Donald Judd, and Jasper Johns, you somehow become human in a way. Or, as Hickey put it, "American art is the cure for the malaise of statistical disembodied life we live here in America. . . . Works of art in their idiosyncrasy and outrageousness have the ability to rescue us from that world if we want to be rescued."

"Why don't we let the art world be what it is, which is a cure for America," Hickey said near the end of his talk, before taking questions from members of the audience.

Join us on November 18th for our third Clarice Smith Lecture when Linda Nochlin will present "Consider the Difference: American Women Artists from Cassatt to Contemporary."

- Dave Hickey, Donald Judd, Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns, Clarice Smith, American Art,

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Posted by Howard on November 4, 2009 in Lectures on American Art

Permalink

| Comments (0)

Discovering 1934: The Stories Behind the Paintings

October 30, 2009

John Cunning's Manhattan Skyline

"What kind of highway signs did they have in Minnesota in 1934?" was just one of the questions Ann Prentice Wagner, guest curator of the exhibition 1934: A New Deal for Artists, needed to answer to place the paintings in context. "I was asking and answering questions of the kind that I hadn't had previously," Wagner told an enthusiastic audience who attended her lecture the other night at American Art.

Berenice Abbott's Brooklyn Bridge, Water and Dock Streets, Brooklyn, from the series Changing New York

The exhibition marks the seventh-fifth anniversary of the Public Works of Art Project, a short-lived New Deal program that began in December 1933 and shut its doors the following June. (The Federal Works Project—same idea, different program--began in 1935 and ended in 1943.) Artists were employed to create artworks that would adorn public buildings and received weekly paychecks to help keep them going during the Great Depression. In December 1933, thousands of artists became workers. They were free to riff on the theme of "the American Scene."

What's amazing to me is that artists joined the ranks of everyday workers, and their efforts were valued, and helping them was considered vital to reviving the nation's soul. "Artists were proud to be American workers, practical workers who produced something valuable for the country," Wagner said. "America could have lost a generation of artists, a grim prospect."

And what did they produce? Mostly scenes of American life in the city as well as in the countryside. You get Manhattan but you also get Minnesota. "They were showing you where they came from and where they worked. They were showing you what they knew best," added Wagner.

But they didn't just document, they often reinterpreted the scene. They were artists first. With the help of Berenice Abbott's black-and-white photographs taken in the mid-1930s in New York, for example, Wagner was able to show the actual setting for John Cunning's Manhattan Skyline. Not only did Cunning remove some coffee-factory signs from the sides of the warehouses and replace them with red brick, he also moved the Brooklyn Bridge to better fit his composition. Cunning, indeed!

In April 1934, five hundred works from the Public Works of Art Project were displayed at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in an event hosted by President and Mrs. Roosevelt. Government agencies could choose artworks for their buildings. The Roosevelts chose thirty-two paintings for the White House, seven of which are on view in the exhibition, including the New York scene Christopher Street, Greenwich Village by Beulah Bettersworth. The current exhibition at American Art runs through January 3, 2010, followed by a national tour.

- Ann Wagner, 1934, The Federal Works Project, Public Works of Art Project, Corcoran Gallery of Art,

American Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Posted by Howard on October 30, 2009 in American Art Here

Permalink

| Comments (2)

Recent Comments