Check out a new feature that I did with Maggie Fick for Al Jazeera. This multimedia piece explores social, cultural and political issues on the border between north and south Sudan.

View it here on Al Jazeera’s website

Be sure to check out the photo gallery, too, by clicking on the “In Pictures” photo to the right of the text column.

Despite significant delays, voter registration finally kicked off today throughout the south.

Thousands of southerners braved searing heat and lines in order to register themselves for January’s referendum.

These are remarkably determined people.

Here are some photos from the first day of voter registration in the north-south border area of Melut.

(some images subject to additional copyright)

Check out a new photo essay I just completed for Foreign Policy Magazine that illustrates the challenges of transforming southern Sudanese security forces.

Great captions by Maggie Fick.

Check out this short video report I put together about the creation of southern Sudan’s national anthem. This is a truly wonderful group of people.

South Sudan National Anthem from Pete Muller on Vimeo.

As I enter this sheet metal cell bloc I am rapidly overwhelmed by the stale smell of tobacco and men. Shackled Nuer tribesmen stare curiously from the shadowy corners of the room. The midday sun beats on the roof; creating heat that brings immediate sweat to my brow. I move cautiously as to not tread on rows of unwashed blankets that signify the nightly sleeping order in this sweltering cage. With no bars between us, the bodies of killers and thieves brush against mine as I move to explore the space. I feel exceptionally foreign, but surprisingly unafraid.

I am reluctant to take pictures of these captive subjects, many of whom seem spiritually defeated. Their situation robs them of any ability to deny my attempts, creating strong pangs of guilt as my hand rests nervously on my camera. I have never worked in a prison before and feel tremendous ethical conflict about doing it now. My work is largely premised on relationships and mutual engagement and the confined status of these men simultaneously repels and attracts me.

“This one is a real killer,” a boyishly young guard explains in broken English. He gestures to half naked man who lays shackled on the floor. While perhaps it shouldn’t, his pointing angers me. Drawing attention to a man and talking about him as though he is not there makes me feel as though I am in a zoo. I contain my frustrations and take a seat on the floor next to the man. I offer him my right hand and touch his shoulder with my left. He seems surprised by my willingness to touch him. I muster a few sentences of Arabic and he seems pleased.

“ I killed a man about six months ago,” he explains through a translator. “He was the husband of a woman that I wanted for myself.” Like the rest of the world, southern Sudan is plagued by adultery and conflict related to it. “The man stabbed me with a spear in the stomach,” he explains, pointing to a gruesome vertical scar that spans the length of his abdomen. “The wound was terrible but I was still had the strength to kill him.”

It is my first known encounter with a killer. Well, perhaps I ought to say a powerless killer. I am sure that I have shaken hands with many powerful politicians in this country and others that have committed crimes of far greater magnitude than this shackled soul. “He is sentenced to death,” one of the guards says. “We are waiting only for the officials orders and then he will be killed.” The guard believes that the orders will arrived in the coming month. Another guard asks the man to confirm that this is true. He affirms with a nod. I feel overwhelming despair.

As I raise my camera to take his picture, he adjusts himself to a more upright position. Like all people, he wants nothing more than to be viewed in a dignified way. He looks directly into the lens and I snap a few frames. It haunts me to know that it will be the last photos anyone every takes of him. I am filled with emotion and naïve compassion for the man but the environment and circumstances prevent me from expressing it. I’ve already taken too long and the guards are anxious to move me away from a crowd growing behind us.

Over an evening beer, I share my thoughts on the encounter with an older Nuer man at a local bar. He explains that killing is not unusual in Nuer culture. “It is something normal for us.”

His remarks leave me thinking about what a strange evolution it must be for Nuer men to face a growing judicial system. Something that was formerly condoned and perhaps even respected is now legal grounds for execution.

The pitfalls of democratization, I suppose.

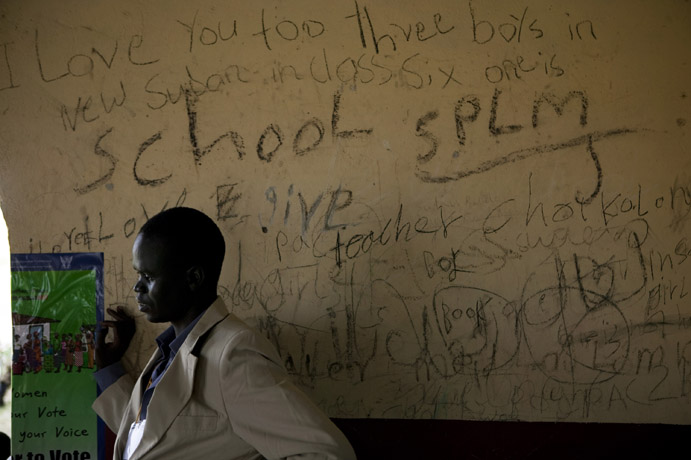

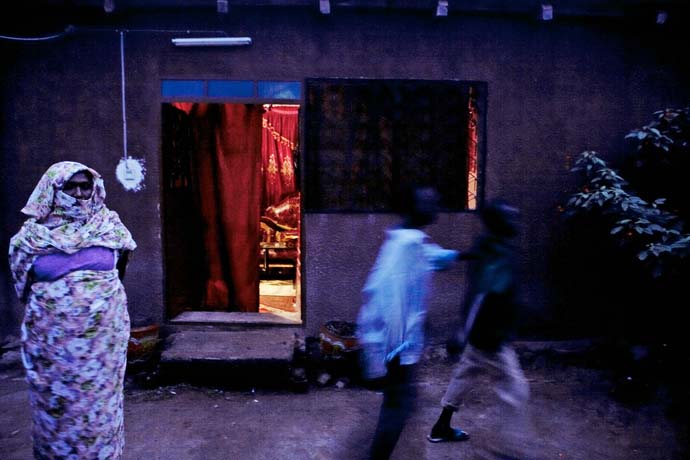

These images are part of a forthcoming feature on border communities in south Sudan’s Upper Nile state. Upper Nile forms the northern most border of southern Sudan and contains a significant amount of the region’s oil wealth.

These photos were taken in the town of Renk, which sits some 30 kilometers south of the Current Border Line (CBL). Renk is a relatively short jaunt from Khartoum, making it a highly mixed community. It is heavily populated by northern Sudanese traders and is a frequent destination for northerners who want a break from the Islamic laws that govern the north. Renk’s lively streets boast an unusual amount of nightlife, including restaurants, bars and shops.

Given Renk’s proximity to northern Sudan and the presence of multinational oil companies, Renk is significantly more developed than most areas of the south. The streets are lined with lights and residents enjoy 24 hour power, two highly uncommon services throughout the area.

Some fear, however, that the culturally mixed nature of border communities like Renk could make for a combustive atmosphere around the referendum. Furthermore, the region’s oil wealth could be a source of conflict between north and south if southerners do opt for secession.

The full story, done in print (by Maggie Fick), photos and video, is slated to appear on Al Jazeera online in the coming days.

Stay tuned.

Hundreds of southern Sudanese turned out on Saturday to support the independence movement that is growing here. Pro-separation marches have become a ritual activity on the 9th of each month, the date on which southern Sudan’s referendum is scheduled to take place in January.

October 9th Video Blog from Pete Muller on Vimeo.

Despite looming concerns that the vote may be delayed due to political and administrative wrangling, southerners seem more resolute than ever that the referendum proceed on schedule.

The referendum commission has announced a tentative start date for voter registration on the 14th of November, leaving a very short window for a massive logistical undertaking. According to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, southerners are mandated to achieve at least 60 percent participation in the referendum in order for the results to be considered valid. The threshold issue has political implications given that pro-independence groups want to ensure that separation supporters are registered. Conversely, in areas where unity sentiments might run higher than others, some believe that registration might be intentionally impeded.

Some here claim that votes for unity will be cast through abstention. If those who support unity register but do not vote, it could exert pressure through the threshold channel.

We hear very little talk of unity here in the south. I wonder, at times, if unity sentiments, while certainly the minority, might be more common than the discourse suggests. The more time I spend in southern Sudan, the more I believe that local level politics play a significant role in determining national sentiment. It seems, at times, that intertribal tensions within the south are paramount in the decision making process. I wonder if some marginalized and/or minority tribes might tacitly support unity based on localized fears of power imbalance. In some remote areas it is hard to imagine groups voting based on macro level considerations.

Dust swirls violently as our helicopter comes to rest on a remote airstrip. After two hours of flying time, I am fidgety and glad to be on the ground. I do a quick check of my equipment and prepare to experience a place that I haven’t before. A young Russian operator cracks the chopper door and a stifling heat floods the cabin. “Welcome to Akobo,” he says in thickly accented English. “Have a nice day.” Travelers navigate a rickety ladder onto cracked soil. The landing strip is crowded with heavily armed soldiers who look worse for the wear.

Akobo is not a place where one typically expects to have a “nice” day. Until about nine months ago, this sand speck of a town was the epicenter of interethnic conflict in southern Sudan. Over the course of several months, a series of massacres took place throughout the county, resulting in death tolls well over 1,000 people. Tens of thousands fled the violence, transforming Akobo town into an overcrowded, makeshift camp for internally displaced persons. Add to the violence an acute food shortage, which prompted some journalists and aid workers to brand Akobo the “hungriest place on earth.” Images of emaciated bodies poured out of Akobo’s antiquated hospital.

As we explore the town, I begin to sense that people here are deeply traumatized. Over the course of a few hours, I pass several people who appear catatonic. A man in his forties stands under a tree while a long line of soldiers, local authorities and foreigners pass only a few meters away. He seems to look directly through us, as though we’re not even there. I greet him in Arabic but receive no response. An elderly woman on the hospital grounds skittishly runs away from me as I cut hastily through the yard. I slow my pace hoping to calm her down but her fear is palpable and she continues to scramble.

Recognizing an unstable, violent and largely uncontrollable environment in Akobo, the international community began targeting considerable funds toward stabilization projects here. “I started throwing every penny I had at Akobo,” explains Leis Grande, the head of the UN’s humanitarian efforts in southern Sudan. “I’ve hauled every news agency and foreign minister I could get my hands on through Akobo. It’s my twelfth visit to the town.” Grande speaks directly and passionately with key figures here. She hugs everyone, an uncommon but highly refreshing gesture. She seems genuinely and deeply concerned about the people she meets.

On a walk back to the helicopter at the end of the day, she describes the process of “flipping” unstable and violent pockets throughout the south. She explains that such areas require tremendous financial investment in an array of sectors including employment, food provision, education and health. “When I first started coming to Akobo, almost none of the kids were in school. Now, we’re got more than 5,000 kids in schools.” She explains that youth employment is critical in conflict areas where teens often comprise large portions of warring forces. Additionally, Grande suggests that the provision of foodstuffs helps reduce conflict in areas where large numbers of people are food insecure.

“I think that Akobo has turned the corner,” she says with cautious optimism. “It takes a lot of intensive effort over the course of at least six months to see serious changes.” She says that the UN, with considerable support form the United States, has targeted fifteen other extreme needs cases throughout southern Sudan. She hopes to “flip” these communities from conflict ridden to stable using a similar model to that employed in Akobo. “We’re up against a lot of challenges. I certainly expect to see some progress in several of those areas but it’s never easy.”

As I take stock of the town, I ponder the prospects for unchecked cruelty in places this remote. Wedged between the border of south Sudan and Ethiopia, Akobo is hundreds of miles from any form of development. During the rain season, it can only be reached by helicopter. I imagine that when people go to war here, few things prevent them from engaging in orgies of violence against their adversaries. There are no intimidating witnesses here, no one to name and shame those responsible for extreme cruelty. With a long history of interethnic violence and such complete isolation, the thought of war here sends chills up my spine.

I hope that Ms. Grande’s feeling that Akobo has turned the corner is correct.

A bit too tired to write much now but here are some snaps from Salva Kiir’s return from the US yesterday. He had been in the States attended the UN meeting on southern Sudan. People were pretty excited to see him.

The Beijing hotel is, without a doubt, the largest “prefab” I’ve ever seen. Its spacious lobby, grandiose theater, connecting hallways and dozens of rooms are constructed solely from plastic slats fastened together in a less than appealing aesthetic. Its entrance is decorated with plastic trees that, at night, glow an array of neon colors.

Last Saturday evening, the Beijing Hotel appropriately hosted the celebration of the 61st anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. Sponsored by the Chinese National Petroleum Company and organized by the Chinese consulate, the event amounted to one of the strangest, albeit entertaining, that I have ever attended.

It commenced with gorgeous Chinese dancers playing drums on a stage that looked prepared to host the Blue Man Group. Blue, orange, green and yellow lights illuminated the dancers as copious amounts of fake smoke gushed from machines on all corners of the stage. The drummers were followed by a team of predictably underage male gymnasts who, despite frequent mistakes in their act, finished every maneuver with a plastic, ear-to-ear smile. The gymnasts made way for a series of renowned Chinese, pop culture entertainers who performed acts ranging from magic, to brass instruments to comedic routines in Mandarin poking fun at Chinese celebrities that no one outside of China has ever heard of.

In the middle of the event, a man from the consulate took the stage to say a few words about the People’s Republic and led the crowd in the Chinese national anthem. Unfortunately, neither he nor any of the other participants spoke a word of English. The presentation’s communication was left to a young, Chinese-American woman who served as the evening’s emcee. With a charming smile, and form fitting black dress she appeared between scenes to explain what would otherwise be lost.

The event was a strong and interesting indication of China’s growing presence in resource-rich areas of Africa. Here in Sudan, China is heavily invested in petro-chemical extraction in the oil rich basins throughout south central areas of the country. When one drives through the oil fields of northern Upper Nile state, it is common to see busloads of Chinese oil workers traveling on out-of-place tarmac roads between processing facilities. There is, in fact, an international airport in the village of Paloich, a tiny speck in the middle of the Melut oil basin. While I do not know for sure, something tells me that the planes that fly in and out are likely destined for China.

I am curious to see how the resource game between east and west unfolds here in Africa. As I watched these Chinese entertainers whose mission, at least in part, is to win popular favor among Sudanese, I could not help but think of the vast cultural gap between China and Africa. Western powers have been involved in Africa for centuries, leaving behind aspects of their customs, practices and languages. While large-scale cultural differences certainly exist between Africans and Westerners, most continental capitals bare the clear marks of past and current relationships with the West. The national powerbrokers in most countries share learned languages and customs with incoming French, Dutch and American investors. Watching a stereotypically Chinese entertainer play a trumpet into the face of a Sudanese parliamentarian seemed like a futile attempt at cultural persuasion.