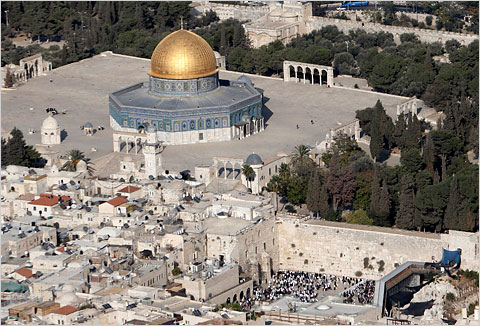

Ronen Zvulun/Reuters Control of Jerusalem’s holy sites have been a stumbling block in pat negotiations.

Ronen Zvulun/Reuters Control of Jerusalem’s holy sites have been a stumbling block in pat negotiations.As my colleagues Helene Cooper and Isabel Kershner report, Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, left Washington after a long meeting with President Obama apparently failed to persuade him to halt the building of homes for Jews in East Jerusalem.

American and Israeli negotiators will continue to talk about how to revive peace talks, but Mr. Netanyahu’s vice prime minister, Silvan Shalom, said on Thursday that the Obama administration’s focus on Jerusalem puzzled him. Mr. Shalom told Israel Radio that construction in the city was “unconditional,” and asked, “How did we get to the point that building in Jerusalem has turned into a stumbling block?”

For all the other difficulties confronting negotiators in the Middle East, the diplomatic storm that began this month during a visit there by America’s vice president has made it clear that the thorniest problem to be solved is finding some way for Israelis and Palestinians to live in two separate states but still share one capital, Jerusalem.

The tension between the United States and Israel began with the announcement, on a day Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. was in Jerusalem, that Israel would build 1,600 more homes for Jews in a part of the city it seized from Jordan during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. That disregard for the possibility that parts of Jerusalem might be placed under Palestinian sovereignty under a peace agreement threatened to derail new talks before they even began.

Then the Israeli Web site Ynet News reported on Tuesday night, just before Mr. Netanyahu met with President Obama at the White House, that another controversial building project would go ahead in East Jerusalem.

Responding to criticism from the American government, Mr. Netanyahu has repeatedly suggested, as he did during a speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (Aipac) in Washington on Monday, that the status of the city is not up for negotiation. “Jerusalem is not a settlement; it’s our capital,” he told Aipac, a pro-Israel lobbying group.

As Laura Rozen noted on Politco’s Web site, the prime minister also said that his position on the city was no different than that of his predecessors:

In Jerusalem, my government has maintained the policies of every single Israeli governments since 1967, including those led by Golda Meir, Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Rabin. …. Everyone knows — everyone: Americans, Europeans, Israelis certainly, Palestinians — that these neighborhoods will be part of Israel in any peace settlement. Therefore, building them in no way precludes the possibility of a two-state solution.

In his book “1967” the Israeli historian Tom Segev explained that Israel’s government quickly made the decision to annex the parts of Jerusalem it took during a week of fighting that year, and from the start treated the city differently from the other territory it occupied in Gaza and the West Bank. He added that officials were initially careful to incorporate East Jerusalem quietly:

The demand to Judaize the city became a popular signifier of patriotism. But the process required restraint, caution and intelligence, so as not to anger “the world” — meaning the Vatican, the U.S. State Department, the U.N., or, God forbid, The New York Times. Israel often tried to mislead “the world.” Minister of Justice Shapira once suggested announcing that the Jewish Quarter had not been expropriated but rather evacuated “for survey needs.” The world, including the United States, was indeed opposed to the annexation of East Jerusalem. Administration officials said so more than once.

That said, Mr. Segev also noted that “the United States did not take action against the de facto annexation, trying only to downplay it as much as possible.”

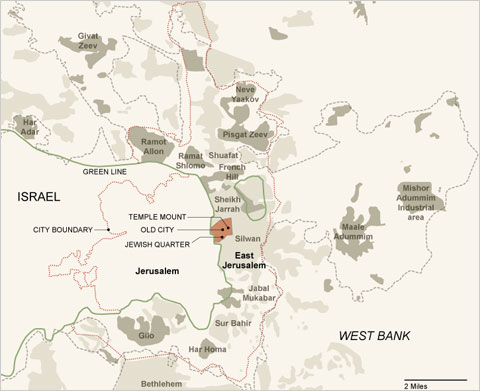

The New York Times A map showing Israeli settlements in parts of Jerusalem beyond the “Green Line,” those areas captured in fighting in 1967. The areas shaded dark gray are Israeli settlements. The dotted red line indicates the current boundary of the city. The dotted gray line shows the location of the barrier Israel is building. Enlarge.

The New York Times A map showing Israeli settlements in parts of Jerusalem beyond the “Green Line,” those areas captured in fighting in 1967. The areas shaded dark gray are Israeli settlements. The dotted red line indicates the current boundary of the city. The dotted gray line shows the location of the barrier Israel is building. Enlarge.While Israeli Israeli officials have become considerably less reticent about acting as if the question of Jerusalem has been settled since 1967 — and while more than 150,000 Jews have moved into housing in the part of the city annexed that year — the international community still generally sees the status of the city as an open question. On Wednesday, the United Nations secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, told the Security Council, “All settlement activity is illegal, but inserting settlers into Palestinian neighborhoods in Jerusalem is particularly troubling.”

As Mr. Segev explained in “One Palestine, Complete,” a history of the era leading up to the creation of the Jewish state, on Nov. 29, 1947, when the United Nations voted to divide Palestine into two states, the question of what to do about the holy city was left open: “Jerusalem was to remain under international control.”

In 1995, Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister who signed the Oslo Accords as a step towards a two-state solution to the conflict with the Palestinians, told the Israeli Parliament:

I said yesterday, and repeat today, that there are not two Jerusalems; there is only one Jerusalem. From our perspective, Jerusalem is not a subject for compromise. Jerusalem was ours, will be ours, is ours and will remain as such forever.

Many of the delegates at this year’s Aipac conference may have wondered how this idea that Jerusalem should remain under Israeli control had become a stumbling block in Israel’s relations with the Obama administration. After all, the president himself, when he was running for office, had assured them that he agreed with that position. To rapturous applause, Mr. Obama told Aipac in 2008:

Let me be clear. Israel’s security is sacrosanct. It is nonnegotiable. The Palestinians need a state that is contiguous and cohesive, and that allows them to prosper — but any agreement with the Palestinian people must preserve Israel’s identity as a Jewish state, with secure, recognized and defensible borders. Jerusalem will remain the capital of Israel, and it must remain undivided.

Almost immediately, that speech caused problems for Mr. Obama. Saeb Erekat, a Palestinian negotiator, told Al Jazeera that next day, “This is the worst thing to happen to us since 1967.” The Palestinian president, Mahmoud Abbas, complained that Mr. Obama was talking about something that was not yet settled as it were, telling reporters, “Jerusalem is part of the six points that are subjects on the negotiations’ agenda.” He added:

The whole world knows that holy Jerusalem was occupied in 1967 and we will not accept a Palestinian state without having Jerusalem as the capital.

Days later, Mr. Obama backtracked, telling CNN that he simply meant that the city would not be physically divided, although it could be shared, in the way President Bill Clinton suggested during negotiations a decade ago:

You know, the truth is that this was an example where we had some poor phrasing in the speech. And we immediately tried to correct the interpretation that was given. The point we were simply making was, is that we don’t want barbed wire running through Jerusalem, similar to the way it was prior to the ‘67 war, that it is possible for us to create a Jerusalem that is cohesive and coherent.

I was not trying to predetermine what are essentially final status issues. I think the Clinton formulation provides a starting point for discussions between the parties.

Robert Malley, an adviser to President Clinton who participated in the Camp David summit meeting in 2000, explained in an article on the negotiations — written with Hussein Agha for The New York Review of Books in August 2001 — that while both sides arrived in the United States that year with stated positions claiming Jerusalem for themselves, both also showed some flexibility on the core issue during the talks.

Of the Palestinians, Mr. Malley and Mr. Agha wrote, “Despite their insistence on Israel’s withdrawal from all lands occupied in 1967, they were open to a division of East Jerusalem granting Israel sovereignty over its Jewish areas (the Jewish Quarter, the Wailing Wall, and the Jewish neighborhoods) in clear contravention of this principle.” As for Ehud Barak, who was then Israel’s prime minister and now serves as the country’s defense minister, they noted: “Coming into office on a pledge to retain Jerusalem as Israel’s ‘eternal and undivided capital,’ he ended up appearing to agree to Palestinian sovereignty—first over some, then over all, of the Arab sectors of East Jerusalem.”

Yet, when push came to shove, the question of who would rule one small part of the city — the holy site known as the Haram al-Sharif to Palestinians and the Temple Mount to Jews — seemed impossible to resolve. At Camp David, Mr. Malley recalled, a fair amount of attention was devoted to was called the “divine sovereignty” compromise:

The Americans spent countless hours seeking imaginative formulations to finesse the issue of which party would enjoy sovereignty over this sacred place—a coalition of nations, the United Nations Security Council, even God himself was proposed. In the end, the Palestinians would have nothing of it: the agreement had to give them sovereignty, or there would be no agreement at all.

Even after the Camp David talks ended, President Clinton tried to keep the idea of letting God rule that sensitive part of Jerusalem alive. After a meeting between the president and Yasir Arafat in New York in September 2000, my colleague Jane Perlez reported:

[T]he Americans were trying desperately to move the discussion away from any form of exclusive sovereignty and toward the concept of shared sovereignty between Israel and the Palestinians, or better still, the concept of ”divine sovereignty.”

According to this idea, the two Muslim shrines at the site, the Dome of the Rock and Al Aksa, and the area under the earth where the First and Second Jewish temples stood, would be under the sovereignty of God, an idea that was once broached by King Hussein during his reign in Jordan.

Later that same month, my colleague Deborah Sontag reported that the proposal was still on the table, but explained that the talks seemed deadlocked on the issue because neither leader was willing to be seen as giving away a site holy to both Muslims and Jews:

Gershom Gorenberg, an expert on the mount, said the site had predictably ended up as the core of the conflict not only because of its religious importance to both sides but also because of its ”mythic value” in their historical narratives.

For secular Israelis, capturing the mount was a pinnacle of Zionism, which made the Jewish homeland more solid by reclaiming the sacred center of Judaism after two millenniums. Religious Jews saw it as the first step toward redemption. For the Palestinians, in contrast, losing the mount became emblematic of all the other losses; regaining it became a driving goal of their nationalist movement. [...]

No Arab leader, Mr. Arafat said, could give away the rock from which Muhammad is said to have leapt to heaven. No Jewish leader, Mr. Barak said, could give away the rock that more or less marks where the temple once stood.

As The Guardian reported that year, Jerusalem’s Roman Catholic Patriarch also came out in favor of the plan to draw God into the talks.

While agreement on the status of the holy city’s holiest site was not reached before the end of Mr. Clinton’s presidency, if the Obama administration hopes for a breakthrough, it may return to the idea of “divine sovereignty.” That said, it is worth remembering that the idea provoked fierce opposition from some Jewish groups when it was proposed a decade ago. In “Divided We Stand: American Jews, Israel,and the Peace Process,” Ofira Seliktar wrote that the Zionist Organization of America sponsored full-page ads in American newspapers saying, “Israel must not surrender Judaism’s holiest site.” The ads said that “no Israeli leader has the right to give away the essence of the Jewish people that is embodied in the Temple Mount.”

Making that sort of compromise now might be close to impossible for Mr. Netanyahu, since his interior minister, Eli Yishai — whose department announced the new building in East Jerusalem during Vice President Biden’s trip — is the leader of the right-wing Shas party, which represents Orthodox Jews.

The Palestinians, too, resisted the plan. As Ms. Sontag reported in late September 2000:

The Palestinians, however, refused to enter into a long-term lease arrangement for their holy space. They also questioned Israeli historical claims that the site was home to the First and Second Temple as well as Jewish traditional beliefs that Adam was created there and that Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac there.

As Mr. Gorenberg, the expert on the holy site, said at the time, the true stumbling block was and remains the need for followers of both religions to accept the legitimacy of the claims of the other: ”If an agreement is reached, then in religious and national terms, the two sides will have agreed to the idea of more than one truth existing in Jerusalem — that there’s more than one way up God’s mountain,” Mr. Gorenberg told Ms. Sontag nearly ten years ago. ”But,” he added, “that’s a big if.”