Making money from stolen paintings — particularly famous ones — is not a straightforward matter, and those who try to do so fall broadly into two categories. The first, most common type is the naïf, who steals a painting but has laid few plans beyond the theft itself. He soon discovers that the painting’s notoriety has rendered it toxic, and he can’t sell it. The work of art becomes burdensome and worthless — to him at least. A more sophisticated criminal, on the other hand, recognizes that a pilfered masterpiece is a unique commodity and that in order to profit from it, he needs to think more like a derivatives trader than a pickpocket.

What Is the Value of Stolen Art?

The space where a Matisse painting hung in the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam, the day it and six other artworks were stolen.

By ED CAESAR

Published: November 13, 2013

The Rotterdam Police, via Associated Press

Top to Bottom: “Reading Girl in White and Yellow,” Matisse; “Woman With Eyes Closed,” Lucian Freud; “Head of a Harlequin,” Picasso.

Billions of dollars’ worth of art goes missing every year, according to the F.B.I., but thefts of high-profile paintings are both infrequent and widely reported. While an open-market sale of works taken in such circumstances is impossible, there continues to be demand for the product, because the rightful owner — a collector, a museum, an insurer — wants the art back. That desire, however nebulous, is what is truly being traded when noteworthy artworks are exchanged on the black market. As long as there is a belief among criminals in the enduring willingness of parties from the legitimate art world to retrieve their property, a stolen painting has currency.

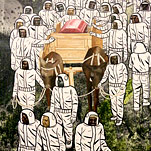

When a couple of men wearing hoods broke into the Kunsthal museum in Rotterdam at 3:22 a.m. on Oct. 16 last year and stole two drawings by Monet and one painting each by Gauguin, Picasso, Matisse, Lucian Freud and Jacob Meyer de Haan, it wasn’t immediately obvious which camp they fell into. There was something businesslike about the burglary itself, which took about two minutes and prompted experienced detectives to suspect an expert crew was responsible. A little more than a year after the heist, however — with the principals having confessed their guilt and the artworks most likely destroyed — we know for sure: They were knuckleheads.

In early October 2012, Radu Dogaru and Eugen Darie, two Romanians from an eastern county called Tulcea were living in the Netherlands. Along with several of their countrymen, according to a criminal indictment, they pursued a variety of hustles, including prostitution and selling stolen watches. One day, Dogaru, the supposed ringleader of this group, unaccountably decided he wanted “great, old art objects” to sell on the black market and resolved to burglarize a museum.

Dogaru and Darie began scouting their options with a stroll through Rotterdam’s museum district. As Darie would reveal when interviewed by Romanian police, the first target they considered was the Natural History Museum, but the place was full of dead animals, and they didn’t see a way to make a profit on such items. (In fact, the Natural History Museum was robbed the previous year of its rhino horns — a commodity whose black-market price in the Far East can run to around $2,000 per ounce, more than the cost of gold or cocaine.)

The Romanians’ attention turned to the Kunsthal next door — a modern, glass-fronted gallery, where a blockbuster exhibition entitled “Avant-Gardes” was about to open. The show comprised some 250 works borrowed from the Triton Collection, belonging to the Cordias, a wealthy Dutch shipping family, and included paintings by Van Gogh and Bonnard, among others. The Romanians didn’t know much about art, but they knew that works by famous artists sold for millions.

The Rotterdam Police, via Associated Press

The painting “Waterloo Bridge, London,” by Claude Monet, was one of several paintings stolen on Oct. 16, 2012, in Rotterdam.

They made several visits to the Kunsthal over the next few days. Dogaru jogged through the park behind the museum a few times to check its security, and on one occasion, the men visited the Kunsthal along with Darie’s girlfriend, posing as art lovers. (The indictment states that on these visits, they placed their hands in the pockets of their sweatpants, to appear nonchalant.) The group sought out paintings on the basis of two criteria: each item had to be by a well-known artist and small enough to fit inside a knapsack.