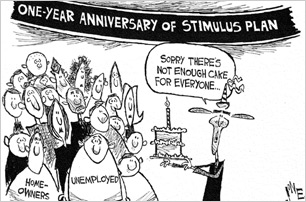

Basically, It's OverA parable about how one nation came to financial ruin.

Updated Sunday, Feb. 21, 2010, at 3:30 PM ET In the early 1700s, Europeans discovered in the Pacific Ocean a large, unpopulated island with a temperate climate, rich in all nature's bounty except coal, oil, and natural gas. Reflecting its lack of civilization, they named this island "Basicland."

In the early 1700s, Europeans discovered in the Pacific Ocean a large, unpopulated island with a temperate climate, rich in all nature's bounty except coal, oil, and natural gas. Reflecting its lack of civilization, they named this island "Basicland."

The Europeans rapidly repopulated Basicland, creating a new nation. They installed a system of government like that of the early United States. There was much encouragement of trade, and no internal tariff or other impediment to such trade. Property rights were greatly respected and strongly enforced. The banking system was simple. It adapted to a national ethos that sought to provide a sound currency, efficient trade, and ample loans for credit-worthy businesses while strongly discouraging loans to the incompetent or for ordinary daily purchases.

Moreover, almost no debt was used to purchase or carry securities or other investments, including real estate and tangible personal property. The one exception was the widespread presence of secured, high-down-payment, fully amortizing, fixed-rate loans on sound houses, other real estate, vehicles, and appliances, to be used by industrious persons who lived within their means. Speculation in Basicland's security and commodity markets was always rigorously discouraged and remained small. There was no trading in options on securities or in derivatives other than "plain vanilla" commodity contracts cleared through responsible exchanges under laws that greatly limited use of financial leverage.

In its first 150 years, the government of Basicland spent no more than 7 percent of its gross domestic product in providing its citizens with essential services such as fire protection, water, sewage and garbage removal, some education, defense forces, courts, and immigration control. A strong family-oriented culture emphasizing duty to relatives, plus considerable private charity, provided the only social safety net.

The tax system was also simple. In the early years, governmental revenues came almost entirely from import duties, and taxes received matched government expenditures. There was never much debt outstanding in the form of government bonds.

As Adam Smith would have expected, GDP per person grew steadily. Indeed, in the modern area it grew in real terms at 3 percent per year, decade after decade, until Basicland led the world in GDP per person. As this happened, taxes on sales, income, property, and payrolls were introduced. Eventually total taxes, matched by total government expenditures, amounted to 35 percent of GDP. The revenue from increased taxes was spent on more government-run education and a substantial government-run social safety net, including medical care and pensions.

A regular increase in such tax-financed government spending, under systems hard to "game" by the unworthy, was considered a moral imperative—a sort of egality-promoting national dividend—so long as growth of such spending was kept well below the growth rate of the country's GDP per person.

Basicland also sought to avoid trouble through a policy that kept imports and exports in near balance, with each amounting to about 25 percent of GDP. Some citizens were initially nervous because 60 percent of imports consisted of absolutely essential coal and oil. But, as the years rolled by with no terrible consequences from this dependency, such worry melted away.

Basicland was exceptionally creditworthy, with no significant deficit ever allowed. And the present value of large "off-book" promises to provide future medical care and pensions appeared unlikely to cause problems, given Basicland's steady 3 percent growth in GDP per person and restraint in making unfunded promises. Basicland seemed to have a system that would long assure its felicity and long induce other nations to follow its example—thus improving the welfare of all humanity.

But even a country as cautious, sound, and generous as Basicland could come to ruin if it failed to address the dangers that can be caused by the ordinary accidents of life. These dangers were significant by 2012, when the extreme prosperity of Basicland had created a peculiar outcome: As their affluence and leisure time grew, Basicland's citizens more and more whiled away their time in the excitement of casino gambling. Most casino revenue now came from bets on security prices under a system used in the 1920s in the United States and called "the bucket shop system."

The winnings of the casinos eventually amounted to 25 percent of Basicland's GDP, while 22 percent of all employee earnings in Basicland were paid to persons employed by the casinos (many of whom were engineers needed elsewhere). So much time was spent at casinos that it amounted to an average of five hours per day for every citizen of Basicland, including newborn babies and the comatose elderly. Many of the gamblers were highly talented engineers attracted partly by casino poker but mostly by bets available in the bucket shop systems, with the bets now called "financial derivatives."

on the Fray

Was the Assassination in Dubai a Success? A Cost-Benefit Analysis.

Was the Assassination in Dubai a Success? A Cost-Benefit Analysis. Maybe John Poindexter's "Total Information Awareness" Wasn't a Terrible Idea

Maybe John Poindexter's "Total Information Awareness" Wasn't a Terrible Idea Can Lil Wayne Bring His $150,000 Grill to Prison With Him?

Can Lil Wayne Bring His $150,000 Grill to Prison With Him? Help! I'm a Soldier Returning From Combat, and People Keep Asking, "Did You Kill Anyone?"

Help! I'm a Soldier Returning From Combat, and People Keep Asking, "Did You Kill Anyone?" Applebaum: What Obama Should Do if Israel Bombs Iran

Applebaum: What Obama Should Do if Israel Bombs Iran Latest Amy Bishop Lunacy: What Is a Herpes Bomb? And Would It Even Work?

Latest Amy Bishop Lunacy: What Is a Herpes Bomb? And Would It Even Work?