2012 Research Highlights

Stanford scholars are engaged in ongoing basic and applied research that creates new knowledge and benefits society. Following are examples from 2012:

Biological Sciences

Researchers produce first complete computer model of an organism

Stanford researchers, led by Markus Covert, assistant professor of bioengineering, reported the first complete computer model of an organism in the journal Cell. The breakthrough used data from more than 900 scientific papers to account for every molecular interaction in the life cycle of Mycoplasma genitalium, the smallest free-living bacterium. The paper fulfills a longstanding goal for the field. Not only does the model allow researchers to address questions that aren’t practical to examine otherwise, it represents a stepping-stone toward the use of computer-aided design in bioengineering and medicine.

Researchers solve plant sex cell mystery

Hybrid seed production in corn is a multibillion-dollar industry, and crossbreeding is fundamental to the production of most other species as well. But despite plant reproduction’s central role in agribusiness, researchers have never answered where plant sex cells come from. The answer, according to Virginia Walbot, professor of biology, and graduate student Timothy Kelliher, is simple: low oxygen levels deep inside the developing flowers are all that is needed to trigger the formation of sex cells. Their work was published in Science.

Professor of Biology Virginia Wolbot with graduate student Tim Kelliher

Professor of Biology Virginia Wolbot with graduate student Tim Kelliher

New analysis provides fuller picture of human expansion from Africa

A review of humans’ anthropological and genetic records has resulted in the most up-to-date story of the “Out of Africa” expansion that occurred about 45,000 to 60,000 years ago. The expansion was outlined in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by geneticists led by Marcus Feldman, the Burnet and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences. The expansion had a dramatic effect on human genetic diversity. As a small group of modern humans migrated out of Africa into Eurasia and the Americas, their genetic diversity was reduced. The review integrates anthropological and archaeological data and could lead to a better understanding of ancient humans.

Business

Good middle managers add to workplace productivity

Middle managers don’t get lots of respect in the workplace, and scholars have mostly studied the worth of CEOs and the efficacy of various management practices. But a Graduate School of Business study suggests that front-line supervisors are far more important than many have thought. Replacing a poorly performing boss with a top-notch middle manager is roughly equivalent to adding one more worker to a nine-member team, according to Kathryn Shaw, the Ernest C. Arbuckle Professor, and Edward Lazear, the Jack Steele Parker Professor of Human Resources Management and Economics, writing in The Value of Bosses.

Why feelings of guilt may signal leadership potential

How people respond to mistakes can be a clue to who they are, according to research by Frank Flynn, the Paul E. Holden Professor of Organizational Behavior, and doctoral student Becky Schaumberg. In two studies, they found an unexpected sign of leadership potential: the tendency to feel guilty. Schaumberg began investigating a possible link between guilt and leadership when she noticed that driven people often mentioned guilt as a motivator. “You don’t usually think of guilt and leadership together, but we started thinking that people would want individuals who feel responsible to be their leaders,” she said.

Too much information clouds negotiators’ judgments

Knowing negotiation partners too well or having the wrong kind of information about them can produce less successful negotiating results than having no information, according to Margaret Neale, the John G. McCoy—Banc One Corporation Professor of Organizations and Dispute Resolution. “To the extent that people rely on information that’s easily available, they may rely on it to the exclusion of doing the hard work necessary to create value in a negotiation,” said Neale.

For the first time, American jobs not following economic growth

Blaming a slow economic recovery for restrained hiring misses the real problem with the unemployment rate, according to Nobel Laureate Michael Spence, dean emeritus of the Graduate School of Business. Structural changes over the last two decades have altered the design of the labor market, making much of its growth hinged on domestic demand, which is virtually nonexistent today. Spence is of author of The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World.

Education

Study finds widening gap between rich and poor students

Sean Reardon, professor of education

Sean Reardon, professor of education

The classroom achievement gap between rich and poor students has grown steadily over the past half-century, according to Sean Reardon, professor of education. Reardon says researchers had expected the relationship between family income and children’s test scores—which are closely related—to remain stable. “The fact that the gap has grown substantially, especially in the last 25 years, was quite surprising, striking and troubling," he said.

California budget woes cripple K-12 reform efforts

Five years ago, Stanford’s Institute for Research on Educational Policy and Practice released a report, “Getting Down to Facts,” on the state of education in California. In 2012, the Stanford Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE) issued a progress report. PACE’s executive director, David Plank, professor of education, found that California still is not spending enough and that budget challenges have snuffed out any appetite for reform of a broken system.

Bringing high school history classes to life

“Reading Like a Historian,” a curriculum under the auspices of the Stanford History Education Group, was introduced in 2008 at five schools in the San Francisco Unified School District. Sam Wineburg, the Margaret Jacks Professor of education, heads the group. Students learn history by analyzing journal writings, memoirs, speeches, songs, photographs, illustrations and other documents of the era. A study evaluating the program showed that participating students outperform their peers.

Education Professor Sam Wineburg discusses “Reading Like a Historian”

Energy

Wireless power could revolutionize highway transportation

A research team has designed a high-efficiency charging system that uses magnetic fields to wirelessly transmit large electric currents between metal coils placed several feet apart. The goal is to develop an all-electric highway that wirelessly charges cars and trucks as they cruise down the road. The technology, described in Applied Physics Letter, has the potential to increase the driving range of electric vehicles, according to Shanhui Fan, professor of electrical engineering.

Wind could meet global power demand by 2030

If the world is to shift to clean energy, electricity generated by the wind will play a major role—and there is more than enough wind for that, according to Mark Z. Jacobson, professor of civil and environmental engineering and a Stanford Woods Institute senior fellow. Jacobson and colleagues at the University of Delaware developed the most sophisticated weather model available to show that not only is there plenty of wind over land and near to shore to provide half the world’s power, but there is enough to exceed the total demand by several times, even after accounting for reductions in wind speed caused by turbines. The findings appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists use microbes to make ‘clean’ methane

Microbes that convert electricity into methane gas could become an important source of renewable energy, according to Stanford and Penn State scientists. The researchers, including Alfred Spormann, professor of chemical engineering and civil and environmental engineering, are raising colonies of microorganisms, called methanogens, which have the ability to turn electrical energy into pure methane – the key ingredient in natural gas. The goal of the research, funded by a Global Climate and Energy Project grant, is to create microbial factories that will transform clean electricity from solar, wind or nuclear power into renewable methane fuel and other chemical compounds.

Stanford Professor Alfred Spormann explaining how to use microbes to make ‘clean’ methane

Engineering

Zhenan Bao, professor of chemical engineering

Zhenan Bao, professor of chemical engineering

Stanford’s touch-sensitive plastic skin heals itself

Chemical engineering Professor Zhenan Bao and her team have made the first synthetic skin that can sense subtle pressure and heal itself when torn or cut at room temperature in about 30 minutes. Their findings, published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, could lead to smarter prosthetics or resilient personal electronics that repair themselves. The team hopes to make the material stretchy and transparent so that it might wrap and overlay electronic devices or display screens.

Researchers advance thought-controlled computer cursors

Researchers led by Krishna Shenoy, professor of electrical engineering, have designed the fastest, most accurate mathematical algorithm yet for brain-implantable prosthetic systems. The systems are designed to help disabled people maneuver computer cursors with their thoughts. The algorithm’s speed, accuracy and natural movement approach those of a real arm. Results related to the algorithm, called ReFIT, were published in Nature Neuroscience.

Tiny wireless chips small enough to travel via blood steam

Researchers, including Ada Poon, assistant professor of electrical engineering, and Teresa Meng, professor of electrical engineering and of computer science, have created a tiny wireless chip, driven by magnetic currents, that’s small enough to travel inside the human body. They hope it will be used for biomedical applications, from delivering drugs to cleaning arteries. Poon is developing medical devices that can be implanted or injected into the human body and powered wirelessly using electromagnetic radio waves. No batteries to wear out. No cables to provide power.

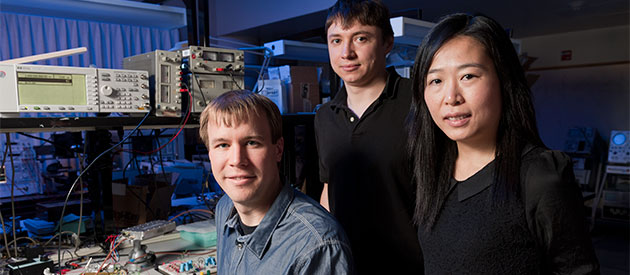

Professor Ada Poon, right, with graduate students Daniel Pivonka, left, and Anatoly Yakovlev

Professor Ada Poon, right, with graduate students Daniel Pivonka, left, and Anatoly Yakovlev

Environment

Biologist and NASA discover Arctic algal blooms

Environmental Earth system science Professor Kevin Arrigo, working with the NASA-sponsored ICESCAPE expedition, discovered a massive phytoplankton bloom underneath the Arctic pack ice in the Chukchi Sea. News of the discovery, something previously considered impossible, was published in Science and is a harbinger of changes in Arctic ecosystems as the planet warms.

Climate change threatens freshwater source for billions

Snowpack, a source of drinking water and agricultural irrigation for billions of people, could shrink significantly within 30 years, according to climate change researcher Noah Diffenbaugh, assistant professor in environmental Earth system science and a Stanford Woods Institute fellow. His study, published in Nature Climate Change, forecasts the effect of climate change on Northern Hemisphere snowpack through the 21st century in the Western United States, Alpine Europe, Central Asia and downstream of the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau. The news is especially troubling for snowpack-dependent California.

Computer models help predict tsunami risk

When a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast of Japan in 2011, it triggered a tsunami that killed more than 20,000 people and destroyed cities. Eric Dunham, assistant professor of geophysics, and Jeremy Kozdon, a postdoctoral research fellow, are creating computational models to pinpoint the cause of the tsunami. Their physics-driven models suggest that the large seafloor uplift and resulting tsunami were caused when seismic waves from the initial earthquake bounced back down from the seafloor above and caused the plates to slip more than had previously been expected. They hope their models will help to predict where future tsunamis might occur.

Carbon capture likely to cause earthquakes

Carbon capture and storage, or CCS, is part of the world’s greenhouse gas reduction strategy. It involves injecting and storing carbon dioxide in underground geologic reservoirs. The method is used at oil and gas exploration sites worldwide to prevent gases from entering the atmosphere. But to significantly reduce emissions, CCS would need to operate on a massive scale. In the journal PNAS, geophysics Professor Mark Zoback and environmental Earth science Professor Steven Gorelick argue that, in many areas, carbon sequestration is likely to create pressure build-up large enough to break the reservoirs’ seals, releasing the stored CO2 and producing temblors.

Stanford faculty Eric Duham and Jeremy Kozdon discuss how computer models can help predict tsunami risk

Humanities

Book focuses on the cultural dimensions of unmanned drones

Communities in Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere in Asia and the Middle East are being watched daily by armed unmanned drones, reminding civilians that their lives are not private. Despite the fact that the drones are breeding contempt on the ground, their numbers are expected to increase. Stanford humanities scholars argue that the national dialogue on drones ignores the historical, cultural and religious perspectives of the people the United States is watching and bombing. Under the Drones: Modern Lives in the Afghanistan-Pakistan Borderlands is a new book edited by Robert Crews, associate professor of history, and Shahzad Bashir, professor of religious studies.

Linguists seek to identify the elusive California accent

With the “Voices of California” project, linguists led by Penelope Eckert, professor of linguistics, have set out to discover and document the diversity of California English. Because there aren’t many stereotypes of California speech compared to the way of speaking associated with such East Coast cities as Boston or New York, a lot of Californians are happy with their perceived lack of accent. The disconnect between the state’s diversity and Californians’ views of their speech as homogenous has proven intriguing. So far, interviews with residents from Merced and Shasta counties have revealed the influence of the Dust Bowl migration from Oklahoma and have highlighted differences between coastal California and the Central Valley.

Professor Penny Eckert and graduate student Kate Greenberg discuss data from the Voice of California project

Professor Penny Eckert and graduate student Kate Greenberg discuss data from the Voice of California project

Maybe Russia’s tsars weren’t so bad after all

It’s a common refrain in Russia that autocratic rule is the best fit for the country because of its history of tyrannical tsars. Not so fast, says historian Nancy Kollmann, who wrote Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Russia. Kollmann says there was more to the country’s justice system between the 15th and 20th centuries than the whims of tsars. Russian law was instead predictable and sensitive to public opinion.

Railroaded, by historian Richard White, recounts the development of the 19th century transcontinental railroad

Railroaded, by historian Richard White, recounts the development of the 19th century transcontinental railroad

White’s Railroaded confronts assumptions about America history

Historian Richard White’s book Railroaded recounts the development of the 19th-century transcontinental railroad by Leland Stanford and others, suggesting that the assumed onset of modernity it prompted was not a good thing. In fact, White suggests that the railroad led to chaos, dysfunction and financial losses. If the railroads had been built a few decades later, American Indians would have had more time to adjust to the inevitable and their reservations would have been structured more advantageously to them. There would have been no senseless cattle industry and overgrazing, no mining industry with its booms and busts and no migration to lands that could not support settlement.

Law

Cuellar investigates how we govern security

The impact of public law depends on how politicians secure control of public organizations and how these organizations, in turn, are used to define national security. Governing Security, by Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, the Stanley Morrison Professor of Law and co-director of the Stanford Center for International Security and Cooperation, investigates the history of two federal agencies that touch the lives of Americans every day: the Roosevelt-era Federal Security Agency (today’s Department of Health and Human Services) and the Department of Homeland Security. Through both, Cuéllar offers an account of developments affecting the basic architecture of our nation.

Michele Landis Dauber is the author of The Sympathetic State

Michele Landis Dauber is the author of The Sympathetic State

Disaster relief and the origins of the American welfare state

Even as unemployment rates in the United States soared during the Great Depression, President Roosevelt’s relief and social security programs faced attacks in Congress and the courts. In response, New Dealers pointed to a tradition—dating to 1790—of federal aid to victims of disaster and sought to paint the Depression as a cataclysmic event. In The Sympathetic State, Michele Landis Dauber, professor of law and Bernard D. Bergreen Faculty Scholar, traces the roots of the modern American welfare state to the earliest days of the republic, when relief was forthcoming for victims of wars, fires, floods, hurricanes and earthquakes.

Trolley car hypothetical case reconsidered

When is it okay to harm some in order to benefit others? For the past 40 years, moral philosophers have wrestled with this question by exploring variants of the following tragic choice. A trolley is traveling down a track, out of control. If it keeps on barreling down the track, it will kill five people. You can’t stop the trolley, but you can flip a switch to divert it to another track, where it will kill only one person. May you flip the switch? Must you flip the switch? In an essay in Philosophical Quarterly, Barbara Fried, the William W. and Gertrude H. Saunders Professor of Law, argues that philosophers’ decades-long preoccupation with these bizarre ‘may I kill one to save five?’ hypotheticals has diverted their attention from the kind of harm/benefit tradeoffs that are ubiquitous in the real world: What restrictions should we put on socially productive activities (driving, manufacturing, developing and marketing new products, constructing new buildings and roads, etc.) that pose some risk of harm to others? The moral principles that philosophers have extracted from their decades-long preoccupation with trolley problems cannot answer this question, and hence largely amount to a moral sideshow. The main attraction—how should we regulate risk—has yet to get serious attention from moral philosophers.

Due process as separation of powers

From its conceptual origin in Magna Carta, due process of law has required that government can deprive persons of rights only pursuant to a coordinated effort of separate institutions that make, execute and adjudicate claims under the law. In Due Process As Separation of Powers, published in the Yale Law Journal, Michael McConnell, the Richard and Frances Mallery Professor of Law and director of the Stanford Constitutional Law Center, maintains that originalist debates about whether the Fifth or Fourteenth amendments were understood to entail modern “substantive due process” have obscured the way that many lawyers and courts understood due process to operate as a mechanism of separation of powers. McConnell and his coauthor maintain that contemporary resorts to originalism to support substantive due process are misplaced.

Medicine

Women feel pain more intensely than men

Women report more intense pain than men in virtually every disease category, according to researchers led by Atul Butte, associate professor of pediatrics. The investigators mined electronic medical records to establish the broad gender difference to a high level of statistical significance. Their study, published in the Journal of Pain, suggests that stronger efforts should be made to recruit women subjects in population and clinical studies to find out why this gender difference exists.

Single antibody shrinks human tumors transplanted into mice

Human tumors transplanted into laboratory mice disappeared or shrank when scientists treated the animals with a single antibody. The researchers were led by Irving Weissman, who directs Stanford’s Institute for Stem Biology and Regenerative Medicine and the Ludwig Center for Cancer Stem Cell Research and Medicine. The antibody works by masking a protein flag on cancer cells that protects them from macrophages and other cells in the immune system. The scientists achieved the findings with human breast, ovarian, colon, bladder, brain, liver and prostate cancer samples. It is the first antibody treatment shown to be broadly effective against a variety of human solid tumors, and the dramatic response has the investigators eager to begin phase-1 and –2 human clinical trials within the next two years.

Integrative 'omics' profile lets scientist discover, track his diabetes onset

For more than two years, geneticist Michael Snyder and his lab members pored over his body’s secrets: the sequence of his DNA, the RNA and proteins produced by his cells, the metabolites and signaling molecules wafting through his blood. They spied on his immune system as it battled viral infections. To his shock, they discovered that he was predisposed to type-2 diabetes and then watched his blood sugar shoot up as he developed the condition during the study. It’s the first eyewitness account — viewed on a molecular level — of the birth of a disease that affects millions and an important milestone in the realization of personalized medicine.

Online tool helps those with BRCA mutations understand options

Women who have a high risk for developing breast and ovarian cancers are now able to access a tool developed by Stanford Cancer Institute researchers, including Allison Kurian, assistant professor of oncology, to wrestle with their tough choices. The interactive tool allows women with known mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes to see what their chances of survival would be after taking different preventive measures at different ages. The tool receives around 1,000 visits per month.

Method allows sequencing of fetal genomes using maternal blood

Researchers have, for the first time, sequenced the genome of an unborn baby using only a blood sample from the mother. Previous whole-genome sequencing required DNA from the father as well as blood from the mother. The research, led by Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson Professor in Engineering and professor of bioengineering and of applied physics, brings fetal genetic testing one step closer to routine clinical use. As the cost of such technology drops, it will become increasingly common to diagnose genetic diseases within the first trimester of pregnancy. The research was published in Nature.

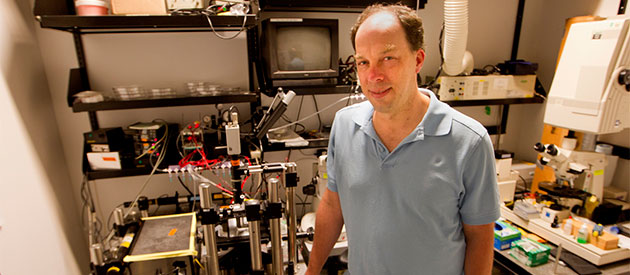

Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson Professor in Engineering

Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson Professor in Engineering

Physical Sciences

BaBar experiment confirms time asymmetry

Time marches forward: watch a movie in reverse, and you’ll quickly see something is amiss. But from the perspective of a single, isolated particle, the passage of time looks the same in either direction: a movie of two particles scattering off of each other would look just as sensible in reverse – a concept known as time reversal symmetry. The BaBar experiment at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory made the first observation of a long-theorized exception to this rule. Digging through nearly 10 years of data from billions of particle collisions, researchers found that certain particle types change into one another much more often in one way than they do in the other, a violation of time-reversal symmetry and confirmation that some subatomic processes have a preferred direction of time. The research was reported in Physical Review Letters.

Galaxy may swarm with 'nomad planets'

Our galaxy may be awash in homeless planets, wandering through space instead of orbiting a star. In fact, there may be 100,000 times more “nomad planets” in the Milky Way than stars, according to a study led by Louis Strigari of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology. If observations confirm the estimate, this new class of celestial objects will affect theories of planet formation and could change understanding of the origin and abundance of life.

Physicists and engineers take first step toward quantum cryptography

A team of physicists has demonstrated a first step in creating a quantum telecommunications device that could be built and implemented using existing infrastructure. Their work appeared in Nature. Quantum mechanics offers the potential to create secure telecommunications networks by harnessing a fundamental phenomenon of quantum particles. The work was done by the research group of Yoshihisa Yamamoto, a professor of applied physics and of electrical engineering, in collaboration with the group of applied physics Professor Martin Fejer.

Molecular graphene heralds new era of ‘designer electrons’

Researchers from Stanford and the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory created the first-ever system of “designer electrons” – exotic variants of ordinary electrons with tunable properties that may ultimately lead to new materials and devices. The research was led by Hari Manoharan, associate professor of physics and a member of SLAC’s Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences. Their first examples, reported in Nature, were hand-crafted, honeycomb-shaped structures inspired by graphene, a pure form of carbon that has been widely heralded for its potential in future electronics.

Stanford and SLAC scientists explain creating ‘designer electrons.’

Social Sciences

Political scientist maps militant groups

What’s the difference between Hamas in Iraq, the Islamic Army in Iraq and the Jihad and Reform Front? All are based in Iraq, but have different historical roots and leadership structures. The differences highlight a challenge to tackling terrorism: understanding the dozens of groups worldwide. Martha Crenshaw, fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, is building a searchable, online map that shows the history and relationships among militant organizations, including detailed descriptions of the groups, dates of leadership changes, major attacks and the beginning and end of relationships with other militant groups.

Study suggests girls can 'rewire' brains to ward off depression

Using fMRI brain imaging and a video game, researchers can teach girls at risk of depression how to train their brains away from negative situations. Early findings from a study led by psychology Professor Ian Gotlib of girls at risk of becoming depressed suggest that such rewiring is possible – and is surprisingly easy. Researchers have been able to teach the girls to change their reaction to negative information and lower their stress levels, which should help ward off depression.

(Psychology Professor Ian Gotlib, left, and postdoctoral researcher Paul Hamilton)

More authority translates to less stress

In a study of high-ranking government and military officials, James Gross, professor of psychology, and a Harvard team found that a higher rank was associated with less anxiety and lower levels of a stress hormone. The study, which appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looked at cortisol measurements and self-reported anxiety within high-ranking government and military officials enrolled in a Harvard executive leadership program. Although evaluating stress is complex, the researchers found that high-ranking leaders were less stressed according to both measures. The strength of the relationship was directly related to rank: the higher the position, the lower the stress.

Center on Poverty and Inequality reveals Recession Trends

David Grusky, professor of sociology and director of the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality (CPI), believes the United States is experiencing a level of economic inequality that hasn’t been seen since the first Gilded Age. CPI’s new Recession Trends website delivers 16 “Recession Briefs” authored by the country's top scholars that lay out the economic and social fallout of the recession. The Recession Trends initiative also acts as a clearinghouse of data on social and economic trends, ranging from housing to crime to mental health.

Multitasking harms development of tweenagers

Tweenage girls who spend hours watching videos and multitasking with digital devices tend to be less successful with social and emotional development, according to Roy Pea, the David Jacks Professor of Education, and Clifford Nass, the Thomas More Storke Professor. But these effects might be warded off with simple face-to-face conversations with other people. Multitasking and spending hours watching videos and using online communication were statistically associated with a series of negative experiences: feeling less social success, not feeling normal, having more friends whom parents perceive as bad influences and sleeping less. The research appeared in Developmental Psychology.

Communication Professor Clifford Nass discusses multitasking