Minaret

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (August 2009) |

- For the mountain formation, see Minarets (California).

Part of a series on |

|

|---|---|

| Architecture | |

|

Arabic · Azeri |

|

| Art | |

|

Calligraphy · Miniature · Rugs |

|

| Dance | |

| Dress | |

|

Abaya · Agal · Boubou |

|

| Holidays | |

|

Ashura · Arba'een · al-Ghadeer |

|

| Literature | |

|

Arabic · Azeri · Bengali |

|

| Islamic Martial Arts | |

| Music | |

| Dastgah · Ghazal · Madih nabawi |

|

| Theatre | |

Minarets (Turkish: minare,[1] from Arabic manāra (lighthouse) منارة, usually مئذنة) are distinctive architectural features of Islamic mosques- generally tall spires with onion-shaped or conical crowns, usually either free standing or taller than any associated support structure; the basic form includes a base, shaft, and gallery. Styles vary regionally and by period. They provide a visual focal point and are used for the call to prayer (adhan).

Contents |

Functions

As well as providing a visual cue to a Muslim community, the main function of the minaret is to provide a vantage point from which the call to prayer is made. The call to prayer is issued five times each day: dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset, and night. In most modern mosques, the adhan is called from the musallah, or prayer hall, via microphone to a speaker system on the minaret. Minarets also function as air conditioning mechanisms: as the sun heats the dome, air is drawn in through open windows then up and out of the minaret, thereby providing natural ventilation.[citation needed]

History

The earliest mosques were built without minarets, the call to prayer was performed elsewhere; hadiths relay that the Muslim community of Madina gave the call to prayer from the roof of the house of Muhammad, which doubled as a place for prayer. Around 80 years after Muhammad's death the first known minarets appeared.[2]

The massive minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia is the world's oldest standing minaret.[3][4] Its construction began during the first third of the 8th century and was completed in 836 CE[5]. The imposing square-plan tower consists of three sections of decreasing size reaching 31.5 meters [5]. Considered as the prototype for minarets of the western Islamic world, it served as a model for many later minarets.[5]

Minarets have been described as the "gate from heaven and earth", and as the Arabic language letter alif (which is a straight vertical line).[6]

The world's tallest minaret, at 210 metres (689ft.) is located at the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, Morocco The world's tallest brick minaret is Qutub Minar located in Delhi, India.[citation needed]

In some of the oldest mosques, such as the Great Mosque of Damascus, minarets originally served as illuminated watchtowers (hence the derivation of the word from the Arabic nur, meaning "light").[citation needed]

Construction

Minarets basic form consist of three parts: a base, shaft, and a gallery. For the base, the ground is excavated until a hard foundation is reached. Gravel and other supporting materials may be used as a foundation; it is unusual for the minaret to be built directly upon ground-level soil. Minarets may be conical (tapering), square, cylindrical, or polygonal (faceted). Stairs circle the shaft in a counter-clockwise fashion, providing necessary structural support to the highly elongated shaft. The gallery is a balcony which encircles the upper sections from which the muezzin may give the call to prayer. It is covered by a roof-like canopy and adorned with ornamentation, such as decorative brick and tile work, cornices, arches and inscriptions, with the transition from the shaft to the gallery typically sporting muqarnas. Originally plain in style, a minaret's origin in time can be determined by its level of ostentation.[citation needed]

Local styles

Styles and architecture can vary widely according to region and time period. Here are a few styles and the localities from which they derive:

- Turkish (11th century)

- 1, 2, 4 or 6 minarets related to the size of the mosque. Slim, circular minarets of equal cross-section are common.

- Egypt (7th century) / Syria (until 13th century)

- Low square towers sitting at the four corners of the mosque.

- Iraq

- For a free-standing conical minaret surrounded by a spiral staircase, see Malwiya.

- Egypt (15th century)

- Octagonal. Two balconies, the upper smaller than the lower, projecting mukarnas, surmounted by an elongated finial.

- Persia (17th century)

- Generally two pairs of slim, blue tile clad towers flanking the mosque entrance, terminating in covered balconies.

- Tatar (18th century)

- A sole minaret is used, placed at the centre of a gabled roof.

- Morocco

- Typically a single square minaret. A notable exception is the octagonal minaret located in Chefchaouen.

- South Asia

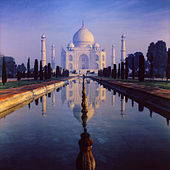

- Octagonal, generally three balconied, with the upper most roofed by an onion dome and topped by a small finial.

Examples

|

Minaret of the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan, in Kairouan, Tunisia, 8th-9th century |

The Charminar in Hyderabad, India |

The six minareted Blue Mosque or Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey. |

|

|

Faisal Mosque Minaret, Islamabad, Pakistan |

The minaret of the Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore, Pakistan |

One of the minarets of the Badshahi Mosque also in Lahore, Pakistan |

|

|

Simple wooden pole used as minaret in Nouadhibou, Mauritania |

The "bare tower" of Huaisheng Mosque, Guangzhou, China |

||

|

Wooden minaret of the Dungan Mosque in Karakol, Kyrgyzstan |

Sabah State Mosque minaret in Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (Borneo). |

Minaret in Wangen bei Olten, Switzerland. |

|

|

Baitul Futuh Mosque minaret in London, United Kingdom. |

Minaret at mosque in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. |

See also

References

- ^ "minaret." Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 21 Mar. 2009.

- ^ Paul Johnson, Civilizations of the Holy Land. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979, p. 173

- ^ Titus Burckhardt, Art of Islam, Language and Meaning: Commemorative Edition. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 128

- ^ Linda Kay Davidson and David Martin Gitlitz, Pilgrimage: from the Ganges to Graceland : an encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. 302

- ^ a b c Minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara Mediterranean Heritage)

- ^ University of London, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Volume 68. The School. 2005. p. 26

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Minarets |