Research in Arizona by anthropologist and archaeologist Michael Wilcox led to a new perspective on indigenous archaeology. (Michael Wilcox)

2010 Research Highlights

Stanford scholars are engaged in ongoing basic and applied research that creates new knowledge and benefits society. Following are examples from 2010:

- Biological Sciences

- Business and Management

- Education

- Engineering

- Environment

- Humanities

- Law

- Medicine

- Physical Sciences

- Social Sciences

Biological Sciences

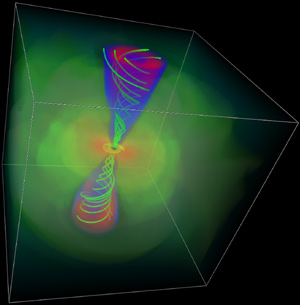

Optogenetics brain-research technique expanded

A team led by Karl Deisseroth, associate professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, reported in Cell about new capabilities in optogenetics to use any visible color of light to control cells and about ways to make cells susceptible to the technique even if they cannot be genetically engineered directly.

Optogenetics, invented by Deisseroth, precisely turns select brain cells on or off with flashes of light. The new capabilities expand the use of optogenetics, which is considered a powerful way to troubleshoot neural circuits associated with depression, Parkinson's disease and other conditions.

Hunting minke whales unjustified

Research by Hopkins Marine Station Director Stephen Palumbi questions hunting of minke whales. (L.A. Cicero)

The killing of Antarctic minke whales has been justified on the theory that their population is booming. A study based on minke DNA, led by Stephen Palumbi, the Harold A. Miller Professor in Marine Sciences and director of the Hopkins Marine Station, concludes that the population is, in fact, not booming.

The team led by Palumbi ran its DNA tests on whale meat from grocery stores in Japan. Their work, published in Molecular Ecology, shows that the current population of Antarctic minke whales is within the historical norm of the species over the last 100,000 years.

What makes us unique? Not necessarily our genes

A team including Michael Snyder, the Stanford W. Ascherman MD, FACS Professor of Genetics, found the key to human individuality may not lie in our genes, but in the sequences that surround and control them – something researchers know little about. The team's research was reported in Science Express.

The discovery suggests that researchers focusing exclusively on genes to learn what makes people different from one another have been looking in the wrong place.

Plant pathogen genetically tailors its attacks

Pathologists had always believed that when a pathogen went on the attack, it used all its weapons. But researchers led by Virginia Walbot, professor of biology, discovered that a tumor-causing corn fungus wields different weapons from its genetic arsenal depending on which part of the plant it infects. The discovery marks the first time tissue-specific targeting has been found in a pathogen.

The research, published in Science and Nature Cancer Reviews, establishes a new principle in plant pathology – that a pathogen can tailor its attack to specifically exploit the tissue or organ properties where it is growing.

Professor Virginia Walbot's research team found that only about 30 percent of the genes in the corn smut genome are always activated, regardless of whether it is in seedlings, adult leaves or the tassel.

Business and Management

Model reflects truthfulness of CEOs

How do you tell if CEOs are being truthful during quarterly earnings conference calls? Graduate School of Business researchers developed a model to analyze the words and phrases used during these calls and found speech patterns that give clues. They studied transcripts of CEOs and CFOs discussing financial results and then looked to see if financial statements were restated at a later point.

David Larcker, the James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting, and doctoral student Anastasia Zakolyukina developed a model to analyze words and phrases based on prior deception detection research conducted by psychologists and linguists. CEOs who were hiding information, for instance, were less likely to say "I" and more likely to use impersonal pronouns and references to general knowledge such as "you know."

Posting calories in restaurants lowers calories

When restaurants post calories on menu boards, a reduction in calories per transaction results, according to researchers at the Graduate School of Business. Based on data provided by Starbucks, Phillip Leslie and Alan Sorensen, both associate professors of economics and strategic management, and doctoral student Bryan Bollinger found that calorie-posting in New York City led to a 6 percent reduction in calories per transaction.

Beverage choices are unaffected by calorie-posting. But calorie-posting leads consumers to buy fewer foods and to switch to lower-calorie foods. Starbucks gave the researchers access to data from locations in New York, Boston and Philadelphia from January 2008 to February 2009.

Money makes hourly workers happy

Jeffrey Pfeffer, the Thomas D. Dee II Professor of Organizational Behavior, and colleagues from the University of Toronto found a stronger tie between money and happiness for people paid by the hour than by salary. Their research was published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

"If you are paid by the hour or account for your time on a timesheet, you begin to see the world in terms of money and in terms of economic evaluation," said Pfeffer. "To the extent that time becomes like money and money becomes more salient, the linkage between how much you earn and your happiness increases."

Study calls for sheltering in place after nuclear attack

In the event of a nuclear detonation, people in large metropolitan areas are better off sheltering in place in basements for 12 to 24 hours than trying to evacuate immediately, unless a lengthy warning period is provided.

That's the conclusion of an analysis led by Lawrence Wein, the Jeffrey S. Skoll Professor of Management Science. Wein modeled the impacts of a detonation in downtown Washington, D.C., and calculated that clogged exit roads would pose more significant risks by exposing evacuees to radiation than if people were to remain in place at the center of large buildings or in basements.

Education

Caution urged in use of student test scores

Linda Darling-Hammond, the Charles E. Ducommun Professor of Education; lead researcher Edward Haertel, the Jacks Family Professor of Education; and Richard Shavelson, the Margaret Jacks Professor of Education, Emeritus, are among the experts who cautioned against reliance on student test scores to evaluate teachers in a report issued by the Economic Policy Institute.

Their report says student test scores are not reliable indicators of teacher effectiveness, even with the addition of value-added modeling. Such modeling allows for more sophisticated comparisons of teachers than were possible in the past. But they are still inaccurate, so test scores should not dominate the information used by school officials in making decisions about the evaluation, discipline and compensation of teachers.

Study identifies best practices in middle grades

High-performing middle schools, regardless of whether they serve students from low- or middle-income families, embrace high expectations and design programs that prepare all students for a rigorous high school education, according to a study by Michael Kirst, professor emeritus of education, and Edward Haertel, the Jacks Family Professor of Education.

Higher-performing schools are distinguished by a school-wide focus on improving student academic outcomes. They also set measurable goals for improved outcomes on standards-based tests, share a mission to prepare students academically for the future and expect students and parents to share the responsibility for student learning. In addition, higher-performing middle-grade schools stress early intervention for struggling students and use data to monitor student progress and improve teacher practice.

Engineering

Electronic skin can feel a butterfly's footsteps

Researchers led by Zhenan Bao, associate professor of chemical engineering, developed an ultrasensitive, highly flexible electronic sensor that can feel a touch as light as an alighting butterfly.

The sensors, announced in Nature Materials, could be used in artificial electronic skin for prosthetic limbs, robots, touch-screen displays, automobile safety and a range of medical applications.

A butterfly tips the scales on a super sensor to determine weight and pressure, part of a Stanford research project on artificial skin.

Same types of cell respond differently to stimulus

Using new technology that allows scientists to monitor how individual cells react in the complex system of cell signaling, researchers led by Markus Covert, assistant professor of bioengineering, uncovered a much larger spectrum of differences between each cell than ever seen before. Cells don’t all act in a uniform fashion, as was previously thought.

Their work, published in Nature, used an imaging system developed at Stanford based on microfluidics and showed that scientists have been misled by the results of previous cell-population-based studies.

Water purification at low cost

Stanford researchers led by Yi Cui, associate professor of materials science and engineering, have developed a water purifying filter that makes the process more than 80,000 times faster than existing filters.

The key, according to research published in Nano Letters, is coating the filter fabric—ordinary cotton—with nanotubes and silver nanowires, then electrifying it. The filter uses very little power, has no moving parts and could be used throughout the developing world.

Ultra-thin solar cells efficiently absorb sunlight

Shanhui Fan, associate professor of electrical engineering, and his team of researchers have shown that a polymer film of a solar cell that is nanoscale-thin and has been roughed up a bit can absorb more than 10 times the energy predicted by conventional theory.

In their research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they say that the key to overcoming the theoretical limit for absorption lies in keeping sunlight in the grip of the solar cell long enough to squeeze the maximum amount of energy from it, using a technique called light trapping.

Casinos filled with secondhand smoke

Secondhand smoke in California's Native American casinos often exceeds concentrations associated with harmful health effects, according to a study headed by Lynn Hildemann, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering.

The casinos, which are exempt from the state's smoking restrictions, are among the few public places in California where smoking is legal. The study of smoke particle concentrations in 36 casinos across the state found that even many nonsmoking areas within the buildings contained smoke concentrations that were several times that of outdoor air. The research was published in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology.

New solar energy conversion process discovered

Researchers led by Nick Melosh, assistant professor of materials science and engineering, discovered a new process that simultaneously combines the light and heat of solar radiation to generate electricity and could offer more than double the efficiency of existing solar cell technology.

The process, called "photon enhanced thermionic emission," could reduce the costs of solar energy production enough for it to compete with oil as an energy source. Unlike photovoltaic technology currently used, the process excels at higher temperatures. Their work was published in Nature Materials.

A new process that simultaneously combines the light and heat of solar radiation to generate electricity could offer more than double the efficiency of existing solar cell technology, say the Stanford engineers who discovered it and proved that it works.

Researchers aim for rapid radiation detection

Shan Wang, professor of materials science and engineering and of electrical engineering, leads a consortium of researchers who think blood proteins may hold the key to developing instruments for use by first responders and labs in the event of nuclear incidents.

Stanford is among nine institutions to earn research contracts to develop a fast, cheap and accurate technology for determining the level of radiation exposure victims might suffer in a nuclear incident.

Environment

Absorbing more light kept the Earth warm

Researchers have long wondered why water on Earth was not frozen during the early days of the planet, when the sun emanated only 70 to 75 percent as much energy as it does today.

A team of researchers, including Dennis Bird, professor of geological and environmental sciences, and Minik Rosing, a geology professor at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, proposed in Nature that the vast global ocean of early Earth absorbed a greater percentage of the incoming solar energy than today's ocean – enough to ward off a frozen planet.

These rocks, billions of years old, tell a new story about the evolution of early Earth.

Heat waves could be common by 2039

Exceptionally long heat waves could become commonplace in the United States in the next 30 years, according to researchers led by Noah Diffenbaugh, assistant professor of environmental Earth system science and a Woods Institute fellow.

"Using a large suite of climate model experiments, we see a clear emergence of much more intense, hot conditions in the U.S. within the next three decades," said Diffenbaugh. Writing in Geophysical Research Letters, he concluded that high temperature extremes could become frequent events in the United States by 2039, posing serious risks to agriculture and human health.

Global warming may lift some from poverty

The impact of global warming on food prices and hunger could be large over the next 20 years. But even as some people are hurt, others would be helped out of poverty, according to a study led by David Lobell, assistant professor of environmental Earth system science and a fellow at the Woods Institute and the Program on Food Security and the Environment.

Lobell, who presented the results at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, said that higher temperatures could significantly reduce yields of wheat, rice and corn – dietary staples for tens of millions of poor people who subsist on less than $1 a day. Still, he said, those who farm their own land may actually benefit from higher crop prices.

Urban CO2 domes increase deaths

Research by Mark Z. Jacobson, professor of civil and environmental engineering and a senior fellow at the Woods Institute, shows for the first time the adverse local health effects of the domes of carbon dioxide that have developed above cities. The results, published in Environmental Science and Technology, show that the domes increase death rates, providing a scientific basis for regulation of CO2.

Jacobson, director of the Atmosphere/Energy Program, also testified on behalf of California's waiver application to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The waiver would allow the state to establish its own carbon dioxide emission standards for vehicles.

In the first study ever done on the local health effects of the domes of carbon dioxide that develop above cities, Stanford researcher Mark Jacobson found that the domes increase the local death rate.

Ocean acidification linked to prehistoric extinction

Researchers led by Jonathan Payne, assistant professor of geological and environmental sciences, believe massive volcanic eruptions were to blame for the ocean acidification that wiped out 90 percent of marine biodiversity in Earth's biggest mass extinction 250 million years ago.

Their results, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looked at calcium found in limestone from Guizhou Province in China. The scientists believe volcanoes spewed carbon dioxide gas that dissolved in the oceans and raised the acidity of seawater. That deadly combination may parallel today's climate change and ocean acidification.

Humanities

Historian explains why the West rules – for now

Ian Morris, the Jean and Rebecca Willard Professor in Classics, contends in Why the West Rules – for Now that destiny is written in geography and that history is a slow, complicated tango between geography and social development.

Morris writes that the world's great civilizations radiated outward from two distinct central cores – the "Hilly Flanks" in western Eurasia and the region between the Yellow and Yangzi rivers in China. The West has enjoyed strategic geographic advantages, especially an abundance of domesticated plants and animals at the end of the last ice age. But while geography drives social development, social development determines what geography means.

Naimark calls for new definition of genocide

In a new book, Stalin's Genocides, historian Norman Naimark, the Robert and Florence McDonnell Professor of Eastern European Studies, argues that we need a much broader definition of genocide – one that includes nations killing social classes and political groups. His case in point: Stalin.

He argues that the Soviet elimination of a social class, the kulaks (who were higher-income farmers), and the subsequent killer famine among all Ukrainian peasants – as well as the notorious 1937 order No. 00447 that called for the mass execution and exile of "socially harmful elements" as "enemies of the people" – were, in fact, genocide.

When it comes to use of the word "genocide," public opinion has been kinder to Stalin than Hitler. But Stanford historian Norman Naimark looks at Stalin's mass killings and urges that the definition of genocide be widened.

Revolutionaries shows how ordinary men are transformed

Pulitzer Prize winner Jack Rakove, the William Robertson Coe Professor of History and American Studies, wrote Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America, which shows how the private lives of the Founding Fathers were suddenly transformed into public careers.

Rakove traces how ordinary men—Washington, Franklin, Madison and Hamilton—were transformed by extraordinary events. None, he argues, set out to become "revolutionary" by ambition, but when events in Boston escalated, they found themselves thrust into a crisis that rapidly led to war.

Why Some Things Should Not Be for Sale

In Why Some Things Should Not Be for Sale, Debra Satz questions the place of markets in a democratic society by looking at markets most people find morally objectionable, like addictive drugs, weapons or human organs.

In a world in which markets are widely recognized as efficient, Satz, the Marta Sutton Weeks Professor of Ethics in Society, draws on history, philosophy, economics and sociology to ask what considerations ought to guide the debates about such markets. She suggests that markets, in fact, shape our culture, foster or thwart human development and create and support structures of power.

Retelling the story of New Mexico’s Native Americans

Michael Wilcox, assistant professor of anthropology, in The Pueblo Revolt and the Mythology of Conquest, corrects the story of New Mexican Native populations while promoting an indigenous approach to archaeology.

Wilcox uses the book to call on fellow scholars to embrace indigenous archaeology to understand Native American history by seeing the connections between artifacts and other scientific evidence and the narratives of living indigenous people. In doing so, he argues, archaeologists could better explain why indigenous populations persist.

Law

How do we deal with discrimination based on looks?

In a new book, The Beauty Bias, Deborah Rhode, the Ernest W. McFarland Professor of Law, says that “prejudice based on appearance is the last bastion of socially and legally acceptable bigotry.”

Rhode, director of the Stanford Center on the Legal Profession, examines why policymakers have not taken up appearance discrimination in her book. She analyzes how this area of the law has been marginalized, arguing that conceptions of attractiveness are so deeply engrained in American culture that we no longer are even aware of our own prejudices.

Lack of Internet regulation decreasing innovation

The design and architecture of the Internet originally led to boundless economic growth and innovation, but due to a lack of governmental regulation and increasing cost barriers, entrepreneurial and application innovation is being increasingly limited.

Barbara van Schewick, associate professor of law and faculty director of the Center for Internet and Society, argues this point in Internet Architecture and Innovation. She identifies elements of the original Internet that fostered innovation—such as little to no cost barriers—and contrasts these features against those of the present-day Internet. Van Schewick examines applications, such as Google, that were developed by students or others with low financial backing and illustrates how these applications would never have gotten off the ground today.

Limited benefits of product liability as compared with costs

The benefits of product liability are only partial in some cases, as compared to the oftentimes more significant costs. A. Mitchell Polinsky, the Josephine Scott Crocker Professor of Law and Economics and director of the John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics, and his co-author, Steven Shavell of Harvard, come to this conclusion in “The Uneasy Case for Product Liability.”

They two analyzed the various costs and benefits of product liability to illustrate that its use is often unwarranted, arguing that—even in the absence of product liability—companies would be motivated by market forces to increase product safety.

Medicine

Study first to analyze genome for disease risk and treatment possibilities

For the first time, researchers led by Euan Ashley, assistant professor of medicine, used a healthy person’s complete genome sequence to predict risk for dozens of diseases and response to common medications. They used the genome of Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson Professsor in the School of Engineering, who last year used a technology he helped invent to sequence his own genome for less than $50,000.

Stephen Quake (left) talks with cardiologist Euan Ashley about his possible disease risks, based on the sequencing of his genome. (Norbert von der Groeben)

The resulting, easy-to-use risk report will likely catapult the use of such data out of the lab and into the waiting room of physicians within the next decade. The research was published in the Lancet, alongside an article about the ethical and practical challenges in such research by Hank Greely, the Deane F. and Kate Edelman Johnson Professor of Law.

Evolution pushed humans toward diabetes risk

Gene variants associated with an increased risk for type-1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis may confer previously unknown benefits to their human carriers, say researchers led by Atul Butte, assistant professor of pediatric cancer biology. As a result, the human race may have been evolving in the recent past to be more susceptible, rather than less, to diabetes.

"Everything we've been taught about evolution would indicate that we should be evolving away from developing it," said Butte. "But instead, we've been evolving toward it." The research was published in PLoS ONE.

Potential drugs to combat hepatitis C identified

Jeffrey Glenn, associate professor of gastroenterology and hepatology and director of the Center for Hepatitis and Liver Tissue Engineering, is among the researchers who have discovered a novel class of compounds that, in experiments in vitro, inhibit replication of the virus responsible for hepatitis C.

If these compounds prove effective in infected humans, they may accelerate efforts to confront this virus' propensity to rapidly acquire drug resistance, while skirting side effects common among current therapies. The research appears in Science Translational Medicine.

Scientists create functional inner-ear cells

Researchers led by otolaryngologist Stefan Heller, the Edward C. and Amy H. Sewall Professor in the School of Medicine, have found a way to develop mouse cells that look and act just like the animal's inner-ear hair cells – the linchpin to hearing and balance – in a petri dish.

The research, published in Cell, could lead to significant scientific and clinical advances along the path to curing deafness in the future if the researchers can further perfect the recipe to generate hair cells in the millions.

Therapy boosts human lymphoma cure rate in mouse models

More than half of laboratory mice with human non-Hodgkin's lymphoma are cured by a treatment involving just two monoclonal antibodies, researchers led by Ravindra Majeti, assistant professor of hematology, have found.

Their findings have laid the groundwork for trials in humans, aided by a grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. The trial combines the activity of rituximab, an antibody currently in use to treat the disorder, with another that blocks a molecule called CD47 on the surface of the cancer cells. Together, the two antibodies synergize to trigger the host's own immune system to eliminate the cancer.

Determining premature infants' risk of illness

Researchers led by Anna Penn, assistant professor of pediatrics, and computer scientist Daphne Koller, the Rajeev Motwani Professor in the School of Engineering, have developed a revolutionary, non-invasive way of quickly predicting the future health of premature infants.

Stanford researchers have developed PhysiScore, a non-invasive way of electronically scoring and assessing a baby's well-being and predicting whether future medical treatment might be needed.

Their new tool, PhysiScore, was announced in Science Translational Medicine. The innovation could better target specialized medical intervention and reduce health care costs. PhysiScore is, essentially, a more reliable, electronic version of the Apgar score, which is a simple assessment done on babies shortly after birth.

Study disproves coronary artery disease marker

A genetic marker touted as a predictor of coronary artery disease is no such thing, according to researchers led by Tom Quertermous, the William G. Irwin Professor in Cardiovascular Medicine, and Themistocles Assimes, assistant professor of medicine.

Their international study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, used more than 17,000 patients with cardiovascular disease and 40,000 others to assess the predictive value of a leading genetic assay for risk of atherosclerosis. The study found no connection.

Embryo survival predicted by research

Two-thirds of all human embryos fail to develop successfully. Researchers led by Renee Reijo Pera, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, have shown that they can predict with 93 percent certainty which fertilized eggs will make it to a critical developmental milestone and which will stall and die.

The findings, reported in Nature Biotechnology, are important to understanding the fundamentals of human development at the earliest stages, which have largely remained a mystery despite the attention given to human embryonic stem cell research. Because the parameters measured by the researchers in this study occur before any embryonic genes are expressed, the results indicate that embryos are likely predestined for survival or death before even the first cell division.

Mouse skin cells turn into neurons

Scientists led by Marius Wernig, assistant professor of pathology and a member of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, have transformed mouse skin cells in a laboratory dish into functional nerve cells with the application of just three genes. The cells make the change without first becoming a pluripotent type of stem cell – a step long thought to be required for cells to acquire new identities.

The findings, which appeared in Nature, could revolutionize the future of human stem cell therapy and recast our understanding of how cells choose and maintain their specialties in the body.

Melanoma-initiating cells identified

Researchers in the laboratory of Irving Weissman, the director of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, identified a cancer-initiating cell in human melanomas.

The finding, published in Nature, is important because the existence of such a cell in the aggressive skin cancer has been a source of debate. It may also explain why current immunotherapies are largely unsuccessful in preventing disease recurrence in human patients.

Physical Sciences

Unpeeling atoms, molecules from the inside out

The world’s first hard X-ray free-electron laser started operations with a bang. First experiments at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory’s Linac Coherent Light Source stripped electrons one by one from neon atoms and nitrogen molecules, removing the electrons from the inside out to create “hollow atoms.”

These early results, published in Nature and Physical Review Letters, described how the Linac Coherent Light Source’s intense pulses of X-ray light change the very atoms and molecules they are designed to image. Understanding how the machine’s ultra-bright X-ray pulses interact with matter is critical for the facility’s goal of making clear, atomic-scale images of biological molecules and movies of chemical processes.

Learning about galaxies from other galaxies

Researchers at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory devised a new way to measure the size and age of the universe and how rapidly it is expanding. The measurement determines a value for the Hubble constant, which indicates the size of the universe, and confirms the age of the universe as 13.75 billion years old, within 170 million years.

Their research, published in the Astrophysical Journal, used a technique called gravitational lensing to measure the distances light traveled from a bright, active galaxy to Earth along different paths. By understanding the time it took light to travel along each path and the effective speeds involved, the researchers inferred how far away the galaxy lies and the overall scale of the universe and some details of its expansion.

Extreme jets take new shape

Recent observations of blazar jets require researchers to look deeper into whether current theories about jet formation and motion require refinement.

Jets of particles streaming from black holes in faraway galaxies operate differently from what was previously thought, according to a study published in Nature. The study, led by scientists at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, revealed that most of a jet's light – gamma rays, the universe's most energetic form of light – is created much farther from the black hole than expected and suggests a more complex shape for the jet.

"As the universe's biggest accelerators, blazar jets are important to understand," said Kavli Research Fellow Masaaki Hayashida. "But how they are produced and how they are structured is not well understood. We're still looking to understand the basics."

"Artificial nose" results from new DNA approach

A new approach to building an "artificial nose" – using fluorescent compounds and DNA – could accelerate the use of sniffing sensors. The research, led by Eric Kool, the George A. and Hilda M. Daubert Professor in Chemistry, was published in Angewandte Chemie.

By sticking fluorescent compounds onto short strands of the molecules that form the backbone of DNA, the researchers produced tiny sensor molecules that change color when they detect certain substances. The sensors are cheap to make and could help devices become widely available.

Desktop experiments could illuminate dark matter

Theorists at the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Science, including Shoucheng Zhang, professor of physics, believe desktop experiments could point the way to dark matter discovery.

Their results, published in Nature Physics, suggest small blocks of matter on a tabletop could reveal elusive properties of the as-yet-unidentified dark matter particles that make up a quarter of the universe, potentially making future large-scale searches easier. The theorists describe an experimental setup that could detect for the first time the axion, a theoretical tiny, lightweight particle conjectured to permeate the universe. The axion, a candidate for the mysterious dark matter particle, has never been observed experimentally.

Bacteria built with arsenic

In a study that could rewrite biology textbooks, scientists at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource helped find the first known living organism that incorporates arsenic into the working parts of its cells.

“It seems that this particular strain of bacteria has actually evolved in a way that it can use arsenic instead of phosphorus to grow and produce life,” said Sam Webb, who led the research at SLAC in collaboration with NASA. “Given that arsenic is usually toxic, this finding is particularly surprising." The results appeared in Science Express.

Social Sciences

Getting older leads to happiness

A study headed by Laura Carstensen, the Fairleigh S. Dickenson, Jr. Professor in Public Policy and director of the Center on Longevity, shows that, as we grow older, we tend to become more emotionally stable. And that translates into longer, more productive lives that offer more benefits than problems.

The study, published in the journal Psychology and Aging, involved tracking about 180 Americans between ages 18 and 94 from 1993 to 2005. For one week every five years, participants carried pagers and responded to periodic quizzes intended to reflect how happy, satisfied and comfortable they were at any given time.

Using social networks to halt the spread of disease

James Holland Jones, associate professor of anthropology, and former postdoctoral fellow Marcel Salathé developed a mathematical model to identify social networks and predict how they'll interact during a disease outbreak.

Developing an algorithm and testing it on Facebook data, they figured out how to identify the social interactions between communities – the relationships most likely to link one group to another and get more people sick. Their work, published in PLoS Computational Biology, could help to head off a future epidemic.

Older investors prone to market mental misfires

When it comes to making risky financial investments, an older mind is likely to make more mistakes than a younger one, psychologists say in a paper in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Researchers led by Brian Knutson, associate professor of psychology, show that older investors make more errors when picking stocks compared to younger people playing the market. And that's not because of senility, memory lapses or other cognitive declines often associated with growing older. Instead, the problem rests with seniors' ability to estimate value, according to functional magnetic resonance imaging results.

Children raised by gays do fine in school

By mining data from the 2000 Census, Michael Rosenfeld, associate professor of sociology, figured out the rates at which kids raised by gay and straight couples repeated a grade during elementary or middle school.

His research, published in Demography, found that children of same-sex parents have essentially the same educational achievement as peers growing up in heterosexual households. Far more important than the sexual orientation of parents are their income and education levels in determining the success of children.

Benefits should pay for housework

A study by Londa Schiebinger, the John L. Hinds Professor in the History of Science, shows academic scientists spend about 19 hours a week on household chores. If universities offered a benefit to pay someone else to do that work, scientists would have more time to spend on the jobs they're trained for, she concluded.

"We're trying to get people more support in the household to lead to a better work-life balance," Schiebinger said. In a paper published in Academe, Schiebinger and co-author Shannon Gilmartin, a research consultant at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research, say partnered female scientists do 54 percent of the basic household chores; partnered male scientists do 28 percent of the cooking, cleaning and laundry.

Cigarette Citadels project targets cigarette manufacturing

Matthew Kohrman, associate professor of anthropology, plotted the international locations of more than 300 cigarette factories under the Cigarette Citadels project of the Stanford Global Tobacco Prevention Research Initiative.

Stanford anthropologist Matthew Kohrman has plotted the international whereabouts of more than 300 cigarette factories, so far. His Cigarette Citadels project gives the public a better understanding of where the tobacco industry operates.

The project is designed to increase the public's understanding of the tobacco industry and to share information that could combat the single largest cause of preventable death. Using tools such as Google Maps, Kohrman has pinpointed the largest clusters of cigarette manufacturers in Europe and Asia.

Researchers prove limits of brain scans as legal evidence

Brain scans are not yet accurate enough to be used as legal evidence. That's the conclusion of a team, writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that included Anthony Wagner, associate professor of psychology; postdoctoral fellow Jesse Rissman; and Hank Greely, the Deane F. and Kate Edelman Johnson Professor of Law.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging to scan the brains of healthy adults, the researchers were able to measure how strong their subjects' sense of a specific memory was. But the researchers could not tell for sure whether the memories themselves were based on recollections of actual experiences.