Music of Palestine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Palestinian music (Arabic: الموسيقى الفلسطينية, al-musiqa-l-filastaniyya, "the Palestinian music") is one of many regional sub-genres of Arabic music. While it shares much in common with Arabic music, both structurally and instrumentally, there are musical forms and subject matter that are distinctively Palestinian.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Historical Development

[edit] Pre-1948

In the areas now controlled by both Israel and the Palestinian National Authority, multiple ethnic groups, races and religions have long held on to a diversity of cultures. Palestinians (including Druze and Bedouin) constituted the largest group, followed by Jews (including Sephardim and Ashkenazim), Egyptians, Cypriots, Samaritans, Circassians Armenians, Dom, and others. Wasif Jawhariyyeh was one oud-player, famous for his post 1904-diary.

Early in the 20th century, most Palestinians lived in rural areas, either as farmers or as nomads. The farmers (fellaheen) sang a variety of work songs, used for tasks like fishing, shepherding, harvesting and making olive oil. Traveling storytellers and musicians called zajaleen were also common, known for their epic tales. Weddings were also home to distinctive music, especially the dabke, a complex dance performed by linked groups of dancers. Popular songs made use of widely-varying forms, particularly the meyjana and dalauna.

[edit] Post-1948

See also:Palestinian music

After the creation of Israel in 1948, large numbers of Arab Palestinians fled to, or were forced into, refugee camps in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The most popular recorded musicians at the time were the superstars of Arab classical music, especially Umm Kulthum and Sayed Darwish. The centers for Palestinian music were in the Israeli towns of Nazareth and Haifa, where performers composed in the classical styles of Cairo and Damascus. A shared Palestinian identity was reflected in a new wave of performers who emerged with distinctively Palestinian themes, relating to the dreams of statehood and the burgeoning nationalist sentiment.

The Israeli government exerted considerable control over Palestinian music recordings within Israel[citation needed], and many of the most popular cassettes were distributed through the black market. Late in the 1970s, a new wave of popular Palestinian stars emerged, including Sabreen and Al Ashiqeen. After the 1987 First Intifada, a more hard-edged group of performers and songwriters emerged, such as al- Funoun, songwriter Suhail Khoury, songwriter Jameel al-Sayih, Thaer Barghouti's Doleh and Sabreen's Mawt a'nabi.

In the 1990s, the Palestinian National Authority was established, and Palestinian cultural expression began to stabilize. Wedding bands, which had all but disappeared during the fighting, reappeared to perform popular Egyptian and Lebanese songs. Other performers to emerge later in the 90s included Yuad, Washem, Mohsen Subhi, Adel Salameh, Issa Boulos, Wissam Joubran,Samir Joubran, and Basel Zayed with his new sound of palestine and Turab group founded in 2004 with the CD Hada Liel . Reem Kelani currently performs Palestinian folk songs.

[edit] Music and identity

Palestinian music reflects Palestinian experience.[3]. As might be expected, much of it deals with the struggle with Israel, the longing for peace, and the love of the land of Palestine. A typical example of such a song is Baladi, Baladi (My Country, My Country), which has become the unofficial Palestinian national anthem:

Palestine, Land of the fathers,

To you, I do not doubt, I will return.

Struggle, revolution, do not die,

For the storm is on the land.[4]

[edit] Palestinian hip hop

Beginning in the late 1990s, Palestinian youth forged a new Palestinian musical sub-genre - Palestinian rap or hip hop - which blends Arabic melodies and Western beats, with lyrics in Arabic, English and even Hebrew.

Borrowing from traditional rap music that first emerged in the ghettos of Los Angeles and New York in the 1970s, "young Palestinian musicians have tailored the style to express their own grievances with the social and political climate in which they live and work"[5]

DAM were pioneers in forging this blend. As Arab citizens of Israel, they rap in Arabic, Hebrew, and English often challenging stereotypes about Palestinians and Arabs head-on in songs like "Meen Erhabe?" ("Who's a terrorist?")

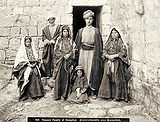

[edit] Musicians and instruments from Jerusalem, anno 1860

|

Tambourine and Zills |

|||

|

Oud player |

[edit] References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Music of Palestine |

- ^ Rima Tarazi (April 2007). "The Palestinian National Song:A Personal Testimony". This Week in Palestine. http://www.thisweekinpalestine.com/details.php?id=2099&ed=139&edid=139.

- ^ William McClure Thomson, (1860): The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land Vol II, p. 578.

- ^ Regev Motti (1993), Oud and Guitar: The Musical Culture of the Arabs in Israel (Institute for Israeli Arab Studies, Beit Berl), ISBN 965-454-002-9, p. 4.

- ^ Babnik and Golani, ed (2006). Musical View on the Conflict in the Middle East. Jerusalem: Minerva Instruction and Consultation Group. ISBN 978-965-7397-03-9.Lyrics by Ali Ismayel.

- ^ Amelia Thomas. "Israeli-Arab rap: an outlet for youth protest". Christian Science Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/2005/0721/p11s01-wome.html?s=widep.

[edit] Books

- Morgan, Andy and Mu'tasem Adileh. "The Sounds of Struggle". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 385-390. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0

[edit] Further reading

- Cohen, Dalia and Ruth Katz (2005). Palestinian Arab Music : A Maqam Tradition in Practice. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11298-5.

- Mashmalon, Micah (1988). Palestinian Folk Songs (Morris Moore Series in Musicology, 4). Shazco. ISBN 9998300916.

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

- Smithsonian Jerusalem Project: Palestinian Music Winter 1999, Issue 3, Jerusalem Quarterly

|

||||||||||||||||||||