State of matter

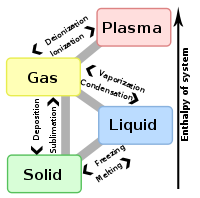

States of matter are the distinct forms that different phases of matter take on. Historically, the distinction is made based on qualitative differences in bulk properties. Solid is the state in which matter maintains a fixed volume and shape; liquid is the state in which matter maintains a fixed volume but adapts to the shape of its container; and gas is the state in which matter expands to occupy whatever volume is available.

States of matter are also distinguished by pressure and temperature conditions, transitioning to other phases as these conditions change to favor their existence; for example, solid transitions to liquid with an increase in temperature.

More recently, distinctions between states have been based on differences in molecular interrelationships. Solid is the state in which intermolecular attractions keep the molecules in fixed spatial relationships. Liquid is the state in which intermolecular attractions keep molecules in proximity, but do not keep the molecules in fixed relationships. Gas is that state in which the molecules are comparatively separated and intermolecular attractions have relatively little effect on their respective motions. Plasma is a highly ionized gas that occurs at high temperatures. The intermolecular forces created by ionic attractions and repulsions give these compositions distinct properties, for which reason plasma is described as a fourth state of matter.[1][2]

Forms of matter that are not composed of molecules and are organized by different forces can also be considered different states of matter. Fermionic condensate and the quark–gluon plasma are examples.

Although solid, gas and liquid are the most common states of matter on Earth, much of the baryonic matter of universe is in the form of hot plasma, both as rarefied interstellar medium and as dense stars.

States of matter may also be defined in terms of phase transitions. A phase transition indicates a change in structure and can be recognized by an abrupt change in properties. By this definition, a distinct state of matter is any set of states distinguished from any other set of states by a phase transition. Water can be said to have several distinct solid states.[3] The appearance of superconductivity is associated with a phase transition, so there are superconductive states. Likewise, liquid crystal states and ferromagnetic states are demarcated by phase transitions and have distinctive properties.

Contents |

[edit] The three classical states

[edit] Solid

The particles (ions, atoms or molecules) are packed closely together. The forces between particles are strong enough so that the particles cannot move freely but can only vibrate. As a result, a solid has a stable, definite shape, and a definite volume. Solids can only change their shape by force, as when broken or cut.

In crystalline solids, the particles (atoms, molecules, or ions) are packed in a regularly ordered, repeating pattern. There are many different crystal structures, and the same substance can have more than one structure (or solid phase). For example, iron has a body-centred cubic structure at temperatures below 912 °C, and a face-centred cubic structure between 912 and 1394 °C. Ice has fifteen known crystal structures, or fifteen solid phases which exist at various temperatures and pressures.[4]

Glasses and other non-crystalline, amorphous solids without long-range order are not thermal equilibrium ground states; therefore they are described below as nonclassical states of matter.

Solids can be transformed into liquids by melting, and liquids can be transformed into solids by freezing. Solids can also change directly into gases through the process of sublimation.

[edit] Liquid

A liquid is a nearly incompressible fluid which is able to conform to the shape of its container but retains a (nearly) constant volume independent of pressure. The volume is definite if the temperature and pressure are constant. When a solid is heated above its melting point, it becomes liquid, given that the pressure is higher than the triple point of the substance. Intermolecular (or interatomic or interionic) forces are still important, but the molecules have enough energy to move relative to each other and the structure is mobile. This means that the shape of a liquid is not definite but is determined by its container. The volume is usually greater than that of the corresponding solid, the most well known exception being water, H2O. The highest temperature at which a given liquid can exist is its critical temperature.[5]

[edit] Gas

A gas is a compressible fluid. Not only will a gas conform to the shape of its container but it will also expand to fill the container.

In a gas, the molecules have enough kinetic energy so that the effect of intermolecular forces is small (or zero for an ideal gas), and the typical distance between neighboring molecules is much greater than the molecular size. A gas has no definite shape or volume, but occupies the entire container in which it is confined. A liquid may be converted to a gas by heating at constant pressure to the boiling point, or else by reducing the pressure at constant temperature.

At temperatures below its critical temperature, a gas is also called a vapor, and can be liquefied by compression alone without cooling. A vapor can exist in equilibrium with a liquid (or solid), in which case the gas pressure equals the vapor pressure of the liquid (or solid).

A supercritical fluid (SCF) is a gas whose temperature and pressure are above the critical temperature and critical pressure respectively. In this state, the distinction between liquid and gas disappears. A supercritical fluid has the physical properties of a gas, but its high density confers solvent properties in some cases which lead to useful applications. For example, supercritical carbon dioxide is used to extract caffeine in the manufacture of decaffeinated coffee.[6]

[edit] Non classical states

[edit] Glass

Glass is a non-crystalline solid material that exhibits a glass transition when heated towards the liquid state. Glasses can be made of quite different classes of materials: anorganic networks (like window glass, made of silicate plus additives), metallic alloys, ionic melts, aqueous solutions, molecular liquids, and polymers. Thermodynamically, a glass is in a metastable state with respect to its crystalline counterpart. The conversion rate, however, is practically zero.

[edit] Crystals with some degree of disorder

A plastic crystal is a molecular solid with long-range positional order but with constituent molecules retaining rotational freedom; in an orientational glass this degree of freedom is frozen in a quenched disordered state.

Similarly, in a spin glass magnetic disorder is frozen.

[edit] Liquid crystal states

Liquid crystal states have properties intermediate between mobile liquids and ordered solids. Generally, they are able to flow like a liquid but exhibiting long-range order. For example, the nematic phase consists of long rod-like molecules such as para-azoxyanisole, which is nematic in the temperature range 118–136 °C.[7] In this state the molecules flow as in a liquid, but they all point in the same direction (within each domain) and cannot rotate freely.

Other types of liquid crystals are described in the main article on these states. Several types have technological importance, for example, in liquid crystal displays.

[edit] Magnetically ordered

Transition metal atoms often have magnetic moments due to the net spin of electrons which remain unpaired and do not form chemical bonds. In some solids the magnetic moments on different atoms are ordered and can form a ferromagnet, an antiferromagnet or a ferrimagnet.

In a ferromagnet—for instance, solid iron—the magnetic moment on each atom is aligned in the same direction (within a magnetic domain). If the domains are also aligned, the solid is a permanent magnet, which is magnetic even in the absence of an external magnetic field. The magnetization disappears when the magnet is heated to the Curie point, which for iron is 768 °C.

An antiferromagnet has two networks of equal and opposite magnetic moments which cancel each other out, so that the net magnetization is zero. For example, in nickel(II) oxide (NiO), half the nickel atoms have moments aligned in one direction and half in the opposite direction.

In a ferrimagnet, the two networks of magnetic moments are opposite but unequal, so that cancellation is incomplete and there is a non-zero net magnetization. An example is magnetite (Fe3O4), which contains Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions with different magnetic moments.

[edit] Low-temperature states

[edit] Superfluids

Close to absolute zero, some liquids form a second liquid state described as superfluid because it has zero viscosity (or infinite fluidity; i.e., flowing without friction). This was discovered in 1937 for helium which forms a superfluid below the lambda temperature of 2.17 K. In this state it will attempt to 'climb' out of its container.[8] It also has infinite thermal conductivity so that no temperature gradient can form in a superfluid. Placing a super fluid in a spinning container will result in quantized vortices.

These properties are explained by the theory that the common isotope helium-4 forms a Bose–Einstein condensate (see next section) in the superfluid state. More recently, Fermionic condensate superfluids have been formed at even lower temperatures by the rare isotope helium-3 and by lithium-6.[9]

[edit] Bose-Einstein condensates

In 1924, Albert Einstein and Satyendra Nath Bose predicted the "Bose-Einstein condensate," sometimes referred to as the fifth state of matter.

In the gas phase, the Bose-Einstein condensate remained an unverified theoretical prediction for many years. In 1995 the research groups of Eric Cornell and Carl Wieman, of JILA at the University of Colorado at Boulder, produced the first such condensate experimentally. A Bose-Einstein condensate is "colder" than a solid. It may occur when atoms have very similar (or the same) quantum levels, at temperatures very close to absolute zero (–273.15 °C).

[edit] Fermionic condensates

A fermionic condensate is similar to the Bose-Einstein condensate but composed of fermions. The Pauli exclusion principle prevents fermions from entering the same quantum state, but a pair of fermions can behave as a boson, and multiple such pairs can then enter the same quantum state without restriction.

[edit] Rydberg molecules

One of the metastable states of strongly non-ideal plasma is Rydberg matter, which forms upon condensation of excited atoms. These atoms can also turn into ions and electrons if they reach a certain temperature. In April 2009, Nature reported the creation of Rydberg molecules from a Rydberg atom and a ground state atom,[10] confirming that such a state of matter could exist.[11] The experiment was performed using ultracold rubidium atoms.

[edit] Quantum Hall states

A quantum Hall state gives rise to quantized Hall voltage measured in the direction perpendicular to the current flow. A quantum spin Hall state is a theoretical phase that may pave the way for the development of electronic devices that dissipate less energy and generate less heat. This is a derivation of the Quantum Hall state of matter.

[edit] Strange matter

Strange matter is a type of quark matter that may exist inside some neutron stars close to the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit (approximately 2–3 solar masses). May be stable at lower energy states once formed.

[edit] High-energy states

[edit] Plasma (ionized gas)

Plasmas or ionized gases can exist at temperatures starting at several thousand degrees Celsius, where they consist of free charged particles, usually in equal numbers, such as ions and electrons. Plasma, like gas, is a state of matter that does not have definite shape or volume. Unlike gases, plasmas may self-generate magnetic fields and electric currents, and respond strongly and collectively to electromagnetic forces.The particles that make up plasmas have electric charges, so plasma can conduct electricity. Two examples of plasma are the charged air produced by lightning, and a star such as our own sun.

As a gas is heated, electrons begin to leave the atoms, resulting in the presence of free electrons, which are not bound to an atom or molecule, and ions, which are chemical species that contain unequal number of electrons and protons, and therefore possess an electrical charge. The free electric charges make the plasma electrically conductive so that it responds strongly to electromagnetic fields. At very high temperatures, such as those present in stars, it is assumed that essentially all electrons are "free," and that a very high-energy plasma is essentially bare nuclei swimming in a sea of electrons. Plasma is the most common state of non-dark matter in the universe.

A plasma can be considered as a gas of highly ionized particles, but the powerful interionic forces lead to distinctly different properties, so that it is usually considered as a different phase or state of matter.

[edit] Quark-gluon plasma

Quark-gluon plasma is a phase in which quarks become free and able to move independently (rather than being perpetually bound into particles) in a sea of gluons (subatomic particles that transmit the strong force that binds quarks together); this is similar to splitting molecules into atoms. This state may be briefly attainable in particle accelerators, and allows scientists to observe the properties of individual quarks, and not just theorize. See also Strangeness production.

Weakly symmetric matter: for up to 10−12 seconds after the Big Bang the strong, weak and electromagnetic forces were unified. Strongly symmetric matter: for up to 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang the energy density of the universe was so high that the four forces of nature — strong, weak, electromagnetic, and gravitational — are thought to have been unified into one single force. As the universe expanded, the temperature and density dropped and the gravitational force separated, a process called symmetry breaking.

Quark-gluon plasma was discovered at CERN in 2000.

[edit] Very high energy states

The gravitational singularity predicted by general relativity to exist at the centre of a black hole is not a phase of matter;[citation needed] it is not a material object at all (although the mass-energy of matter contributed to its creation) but rather a region which the known laws of physics are inadequate to describe.[citation needed]

[edit] Other proposed states

[edit] Degenerate matter

Under extremely high pressure, ordinary matter undergoes a transition to a series of exotic states of matter collectively known as degenerate matter. In these conditions, the structure of matter is supported by the Pauli exclusion principle. These are of great interest to astrophysics, because these high-pressure conditions are believed to exist inside stars that have used up their nuclear fusion "fuel", such as white dwarfs and neutron stars.

Electron-degenerate matter is found inside white dwarf stars. Electrons remain bound to atoms but are able to transfer to adjacent atoms. Neutron-degenerate matter is found in neutron stars. Vast gravitational pressure compresses atoms so strongly that the electrons are forced to combine with protons via inverse beta-decay, resulting in a superdense conglomeration of neutrons. (Normally free neutrons outside an atomic nucleus will decay with a half life of just under 15 minutes, but in a neutron star, as in the nucleus of an atom, other effects stabilize the neutrons.)

[edit] Supersolid

A supersolid is a spatially ordered material (that is, a solid or crystal) with superfluid properties. Similar to a superfluid, a supersolid is able to move without friction but retains a rigid shape. Although a supersolid is a solid, it exhibits so many characteristic properties different from other solids that many argue it is another state of matter.[12]

[edit] String-net liquid

In a string-net liquid, atoms have apparently unstable arrangement, like a liquid, but are still consistent in overall pattern, like a solid. When in a normal solid state, the atoms of matter align themselves in a grid pattern, so that the spin of any electron is the opposite of the spin of all electrons touching it. But in a string-net liquid, atoms are arranged in some pattern which would require some electrons to have neighbors with the same spin. This gives rise to curious properties, as well as supporting some unusual proposals about the fundamental conditions of the universe itself.

[edit] Superglass

A superglass is a phase of matter which is characterized at the same time by superfluidity and a frozen amorphous structure.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes and references

- ^ D.L. Goodstein (1985). States of Matter. Dover Phoenix. ISBN 978-0486495064.

- ^ A.P. Sutton (1993). Electronic Structure of Materials. Oxford Science Publications. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0198517542.

- ^ M. Chaplin (20 August 2009). "Water phase Diagram". Water Structure and Science. http://www.lsbu.ac.uk/water/phase.html. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ M.A. Wahab (2005). Solid State Physics: Structure and Properties of Materials. Alpha Science. pp. 1–3. ISBN 1842652184.

- ^ F. White (2003). Fluid Mechanics. McGraw-Hill. p. 4. ISBN 0-07-240217-2.

- ^ G. Turrell (1997). Gas Dynamics: Theory and Applications. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 3–5. ISBN 0471975737. http://books.google.com/?id=-6qF7TKfiNIC&pg=PA3.

- ^ Shao, Y.; Zerda, T. W. (1998). "Phase Transitions of Liquid Crystal PAA in Confined Geometries". Journal of Physical Chemistry B 102 (18): 3387–3394. doi:10.1021/jp9734437.

- ^ J.R. Minkel (20 February 2009). "Strange but True: Superfluid Helium Can Climb Walls". Scientific American. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=superfluid-can-climb-walls. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ L. Valigra (22 June 2005). "MIT physicists create new form of matter". MIT News. http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2005/matter.html. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ V. Bendkowsky et al. (2009). "Observation of Ultralong-Range Rydberg Molecules". Nature 458 (7241): 1005. doi:10.1038/nature07945. PMID 19396141.

- ^ V. Gill (23 April 2009). "World First for Strange Molecule". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8013343.stm. Retrieved 2010-02-23.

- ^ G. Murthy et al. (1997). "Superfluids and Supersolids on Frustrated Two-Dimensional Lattices". Physical Review B 55: 3104. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.55.3104.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: State of aggregation |

- 2005-06-22, MIT News: MIT physicists create new form of matter Citat: "... They have become the first to create a new type of matter, a gas of atoms that shows high-temperature superfluidity."

- 2003-10-10, Science Daily: Metallic Phase For Bosons Implies New State Of Matter

- 2004-01-15, ScienceDaily: Probable Discovery Of A New, Supersolid, Phase Of Matter Citat: "...We apparently have observed, for the first time, a solid material with the characteristics of a superfluid...but because all its particles are in the identical quantum state, it remains a solid even though its component particles are continually flowing..."

- 2004-01-29, ScienceDaily: NIST/University Of Colorado Scientists Create New Form Of Matter: A Fermionic Condensate

- Short videos demonstrating of States of Matter, solids, liquids and gases by Prof. J M Murrell, University of Sussex

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||