Samuel P. Huntington

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Samuel Phillips Huntington | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | April 18, 1927 New York City, United States |

| Died | December 24, 2008 (aged 81) Martha's Vineyard Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Political science |

| Institutions | Harvard University |

| Alma mater | Stuyvesant High School Harvard University University of Chicago Yale University |

| Known for | Clash of Civilizations |

Samuel Phillips Huntington (April 18, 1927 – December 24, 2008) was an American political scientist who gained wider prominence through his Clash of Civilizations (1993, 1996) thesis of a post-Cold War new world order.

Contents |

[edit] Biographical details

Huntington was born on April 18, 1927, in New York City.[1] He graduated with distinction from Yale University at age 18, served in the U.S. Army, earned his Master's degree from the University of Chicago, and completed his Ph.D. at Harvard University where he began teaching at age 23.[2] He was a member of Harvard's department of government from 1950 until he was denied tenure in 1959.[3] From 1959 to 1962 he was an associate professor of government at Columbia University where he was also Deputy Director of The Institute for War and Peace Studies. Huntington was invited to return to Harvard with tenure in 1963 and remained their until his death. Huntington and Warren Demian Manshel co-founded and co-edited Foreign Policy. Huntington stayed as co-editor until 1977.[4]

His first major book was The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations, (1957) which was highly controversial when it was published but today is regarded as the most influential book on American civil-military relations.[5][6][7] He became prominent with his Political Order in Changing Societies (1968), a work that challenged the conventional view of modernization theorists, that economic and social progress would produce stable democracies in recently decolonized countries. As a consultant to the U.S. Department of State, and in an influential 1968 article in Foreign Affairs, he advocated the concentration of the rural population of South Vietnam as a means of isolating the Viet Cong. He also was co-author of The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies, a report issued by the Trilateral Commission in 1976. During 1977 and 1978, in the administration of Jimmy Carter, he was the White House Coordinator of Security Planning for the National Security Council.

Huntington died on December 24, 2008 at age 81 in Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts.[1]

[edit] Notable arguments

[edit] Political Order in Changing Societies

In 1968, just as the United States' war in Vietnam was reaching its apex, Huntington published Political Order in Changing Societies, which was a critique of the modernization theory which had driven much US policy in the developing world in the prior decade.

Huntington argues that, as societies modernize, they become more complex and disordered. If the process of social modernization that produces this disorder is not matched by a process of political and institutional modernization—a process which produces political institutions capable of managing the stress of modernization—the result may be violence.

In the 1970s, Huntington applied his theoretical insights as an advisor to governments, both democratic and dictatorial. In 1972, he met with Medici government representatives in Brazil; a year later he published the report "Approaches to Political Decompression", warning against the risks of a too-rapid political liberalization, proposing graduated liberalization, and a strong party state modeled upon the image of the Mexican Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). After a prolonged transition, Brazil became democratic in 1985.

Huntington frequently cited Brazil as a success, alluding to his role in his 1988 presidential address to the American Political Science Association, commenting that political science played a modest role in this process. Critics, such as British political scientist Alan Hooper, note that contemporary Brazil has an especially unstable party system, wherein the best institutionalized party, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva's Workers' Party emerged in opposition to controlled-transition. Moreover, Hooper claims that the lack of civil participation in contemporary Brazil stems from that top-down process of political participation transitions.

[edit] The Third Wave of Democratization

In his 1991 book with the same title he makes the argument that beginning with Portugal's revolution in 1974, there has been a third wave of democratization which describes a global trend which includes more than 60 countries throughout Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa who have undergone some form of democratic transitions.

[edit] The Clash of Civilizations

In 1993, Professor Huntington provoked great debate among international relations theorists with the interrogatively-titled "The Clash of Civilizations?", an extremely influential, oft-cited article published in Foreign Affairs magazine. Its description of post–Cold War geopolitics contrasted with the influential End of History thesis advocated by Francis Fukuyama.

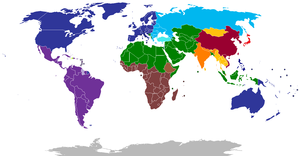

Huntington expanded "The Clash of Civilizations?" to book length and published it as The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order in 1996. The article and the book posit that post–Cold War conflict would most frequently and violently occur because of cultural rather than ideological differences. That, whilst in the Cold War, conflict likely occurred between the Capitalist West and the Communist Bloc East, it now was most likely to occur between the world's major civilizations — identifying seven, and a possible eighth: (i) Western, (ii) Latin American, (iii) Islamic, (iv) Sinic (Chinese), (v) Hindu, (vi) Orthodox, (vii) Japanese, and (viii) the African. This cultural organization contrasts the contemporary world with the classical notion of sovereign states. To understand current and future conflict, cultural rifts must be understood, and culture — rather than the State — must be accepted as the locus of war. Thus, Western nations will lose predominance if they fail to recognize the irreconcilable nature of cultural tensions.

Critics (for example articles in Le Monde Diplomatique) call The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order the theoretical legitimization of American-led Western aggression against China and the world's Islamic cultures. Nevertheless, this post–Cold War shift in geopolitical organization and structure requires that the West internally strengthen itself culturally, by abandoning the imposition of its ideal of democratic universalism and its incessant military interventionism. Other critics argue that Prof. Huntington's taxonomy is simplistic and arbitrary, and does not take account of the internal dynamics and partisan tensions within civilizations. Furthermore, critics argue that Huntington neglects ideological mobilization by elites and unfulfilled socioeconomic needs of the population as the real causal factors driving conflict, that he ignores conflicts that do not fit well with the civilizational fault lines identified by him, and they charge that his new paradigm is nothing but realist thinking in which "states" became replaced by "civilizations"[8]. Huntington's influence upon U.S. policy has been likened to that of British historian A.J. Toynbee's controversial religious theories about Asian leaders in the early twentieth century.

The New York Times obituary on Samuel Huntington notes, however, that his "emphasis on ancient religious empires, as opposed to states or ethnicities, [as sources of global conflict] gained...more cachet after the Sept. 11 attacks."[9]

[edit] Who Are We and immigration

Professor Huntington's last book, Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity, was published in May 2004. Its subject is the meaning of American national identity and the possible cultural threat posed to it by large-scale Latino immigration, which Huntington warns could "divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages".

There is criticism about this book. For an example see Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity.

[edit] Other

Huntington is credited with coining the phrase Davos Man, referring to global elites who "have little need for national loyalty, view national boundaries as obstacles that thankfully are vanishing, and see national governments as residues from the past whose only useful function is to facilitate the elite's global operations". The phrase refers to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where leaders of the global economy meet.[10]

[edit] The National Academy of Sciences controversy

In 1986, Huntington was nominated for membership to the National Academy of Sciences, with his nomination voted on by the entire academy, but most votes, by scientists mainly unfamiliar with the nominee, being token votes. Professor Serge Lang, a Yale University mathematician, disturbed this electoral status quo by challenging Huntington's nomination. Lang campaigned for others to deny Huntington membership, and eventually succeeded; Huntington was twice nominated and twice rejected. A detailed description of these events was published by Lang in Academia, Journalism, and Politics: A Case Study: The Huntington Case which occupies the first 222 pages of his 1998 book Challenges.[11]

In the book Political Order in Changing Societies that Huntington published in 1968 he used, Lang alleged, pseudo-mathematical arguments to argue that in the 1960s South Africa was a "satisfied society". Lang didn't believe the conclusion, so he looked how Huntington justified this claim and concluded that he used methodology which was simply not valid. Lang suspected that he was using false pseudo-mathematical argument to give arguments that he wanted to justify greater authority. It was, said Lang:-

... a type of language which gives the illusion of science without any of its substance.

Huntington's prominence as a Harvard professor and (as then) Director of Harvard's Center for International Affairs contributed to much reportage by The New York Times newspaper and The New Republic magazine of his defeated nomination to the NAS.

Lang was inspired by the writings of mathematician Neal Koblitz who accused Huntington of misusing mathematics and engaging in pseudo-science. Lang claimed that Huntington distorted the historical record and used pseudo-mathematics to make his conclusions appear convincing. Lang documents his accusations in his book Challenges.

Huntington’s supporters included Herbert Simon, a 1978 Nobel Laureate in Economics. The Mathematical Intelligencer offered Simon and Koblitz an opportunity to engage in a written debate, which they accepted.

[edit] Quotations

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Samuel P. Huntington |

- It is my hypothesis that the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will not be primarily ideological or primarily economic. The great divisions among humankind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. Nation-states will remain the most powerful actors in world affairs, but the principal conflicts of global politics will occur between nations and groups of different civilizations. The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics. The fault lines between civilizations will be the battle lines of the future.

- The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion, but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact, non-Westerners never do —— The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, p. 51.

- Hypocrisy, double standards, and "but nots" are the price of universalist pretensions. Democracy is promoted, but not if it brings Islamic fundamentalists to power; nonproliferation is preached for Iran and Iraq, but not for Israel; free trade is the elixir of economic growth, but not for agriculture; human rights are an issue for China, but not with Saudi Arabia; aggression against oil-owning Kuwaitis is massively repulsed, but not against non-oil-owning Bosnians. Double standards in practice are the unavoidable price of universal standards of principle —— The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, p. 184.

- In the emerging world of ethnic conflict and civilizational clash, Western belief in the universality of Western culture suffers three problems: it is false; it is immoral; and it is dangerous . . . Imperialism is the necessary logical consequence of universalism —— The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, p. 310.

- In Eurasia the great historic fault lines between civilizations are once more aflame. This is particularly true along the boundaries of the crescent-shaped Islamic bloc of nations, from the bulge of Africa to central Asia. Violence also occurs between Muslims, on the one hand, and Orthodox Serbs in the Balkans, Jews in Israel, Hindus in India, Buddhists in Burma and Catholics in the Philippines. Islam has bloody borders —— "The Clash of Civilizations?", original 1993 "Foreign Affairs" magazine article.

- Islam's borders are bloody and so are its innards. The fundamental problem for the West is not Islamic fundamentalism. It is Islam, a different civilisation whose people are convinced of the superiority of their culture and are obsessed with the inferiority of their power —— Huntington's 1998 text The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order.

- Cultural America is under siege. And as the Soviet experience illustrates, ideology is a weak glue to hold together people otherwise lacking racial, ethnic, and cultural sources of community —— Who Are We? America's Great Debate, p. 12.

- The effective operation of a democratic political system usually requires some measure of apathy and noninvolvement on the part of some individuals and groups. —— Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission

- A government which lacks authority will have little ability short of cataclysmic crisis to impose on its people the sacrifices which may be necessary... We have come to recognize that there are potential desirable limits to economic growth. There are also potentially desirable limits to the indefinite extension of political democracy.

- Such a transformation would not only revolutionize the United States, but it would also have serious consequences for Hispanics, who will be in the United States but not of it. Sosa ends his book, The Americano Dream, with encouragement for aspiring Hispanic entrepreneurs. "The Americano dream?" he asks. "It exists, it is realistic, and it is there for all of us to share." Sosa is wrong. There is no Americano dream. There is only the American dream created by an Anglo-Protestant society. Mexican-Americans will share in that dream and in that society only if they dream in English. - "The Hispanic Challenge" from Foreign Policy, p. 45.

- A world without U.S. primacy will be a world with more violence and disorder and less democracy and economic growth than a world where the United States continues to have more influence than any other country in shaping global affairs. The sustained international primacy of the United States is central to the welfare and security of Americans and to the future of freedom, democracy, open economies, and international order in the world. - "Why International Primacy Matters," International Security (Spring 1993):83.

[edit] Selected publications

- The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations (1957),

- The Common Defense: Strategic Programs in National Politics (1961),

- Political Order in Changing Societies (1968),

- The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies (1976),

- American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony (1981),

- The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (1991),

- The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1996),

- Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity (2004), an article based on the book is available after (free) registration at Foreign Policy

- Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (2000)

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b Hart, Dan (December 27, 2008). "Samuel Huntington, Harvard Political Scientist, Dies". Bloomberg News.

- ^ "Samuel Huntington, Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor". Department of Government, Harvard University. http://www.gov.harvard.edu/faculty/shuntington/. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/obituaries/article5408079.ece

- ^ http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2009/02/samuel-huntington-81-political-scientist-scholar/

- ^ Michael C. Desch. 1998. "Soldiers, States, and Structures: The End of the Cold War and Weakening U.S. Civilian Control." Armed Forces & Society. 24(3): 389-405.

- ^ Michael C. Desch. 2001. Civilian Control of the Military: The Changing Security Environment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Peter D. Feaver. 1996. “An American Crisis in Civilian Control and Civil-Military Relations?” The Tocqueville Review. 17(1): 159.

- ^ see Richard E. Rubenstein and Jarle Crocker (1994): Challenging Huntington, in: Foreign Policy, No. 96 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 113-128

- ^ Samuel P. Huntington of Harvard Dies at 81, The New York Times, December 27, 2008

- ^ Davos man's death wish, The Guardian, 3 February 2006

- ^ Serge Lang (1999). "Challenges". http://books.google.com/books?id=0avTrkyT1VcC&pg=PA560&dq=%22A+case+study%22+intitle:Challenges+inauthor:Serge+inauthor:Lang&lr=&as_brr=0&sig=SVjRSA1oN5MbUah_e3M3lk4KJAs#PPP10,M1C.

[edit] External links

|

|

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive and inappropriate external links or by converting links into references. (January 2009) |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Samuel P. Huntington |

- The Crisis of Democracy, by Samuel Huntington

- Sam Huntington discusses "Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity" with Jenny Attiyeh on Thoughtcast

- José Antonio Aguilar on "Who Are We? by Samuel Huntington

- A list of comments, mainly critical ones, on Who Are We on Foreign Policy, available to (freely) registered users. Among the writers are a number of eminent scholars of immigration and Latin American studies.

- Professor Edward Said's critique of Huntington's 'Clash of Civilizations' theory.

- An article by Alan Hooper that criticizes the impact of Huntington's advice during the transition process on the quality of democracy in Brazil.

- "Your New Enemies" by Said Shirazi, a leftist critique of Huntington.

- "Interview with Sam Huntington" by Amina R. Chaudary - a 2006 Interview with Islamica Magazine

- A Critique of Clash of Civilization by the late Edward Said

- "The Paradigm Problem: Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis and the search to define a global strategic paradigm" by Emmet McElhatton

- Judaism, Christianity and Islam - A Clash of Civilizations or Evolutionary Succession?

- Wars of Civilizations and Why Huntington's theory appeals to the Western Mind