United Students of Iran

by TARA MAHTAFAR in Washington, D.C.

17 Dec 2009 20:106 Comments

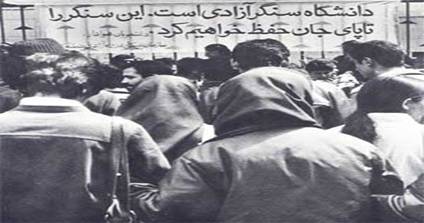

[ feature ] The large campus protests in more than 15 cities across Iran on Dec. 7 in celebration of Student Day, which coincided with the six-month milestone in the country's enduring pro-democracy movement, attested to the role of students at the forefront of the Iranian opposition.

[ feature ] The large campus protests in more than 15 cities across Iran on Dec. 7 in celebration of Student Day, which coincided with the six-month milestone in the country's enduring pro-democracy movement, attested to the role of students at the forefront of the Iranian opposition.

Unlike the country's atomized labor unions and relatively younger women's rights groups, Iran's student movement has deep roots, cultivated well before the revolution when universities -- particularly the schools in Tehran -- served as strongholds for progressive ideas and political activism. In fact, Student Day itself commemorates the deaths of three Iranian students who died protesting the rule of the Shah in 1953. After the Revolution, the Islamic Republic consolidated the network of student associations across the country into a nationwide union called Daftar Tahkim Vahdat, the Office to Consolidate Unity.

This student body of 2009, however, no longer adheres to the agenda defined by the Islamic revolutionary leaders of 1979, and more closely resembles the anti-Shah protesters of 1953. The trajectory of Daftar Tahkim from its ideologically-driven inception to its dissident voice today traces the development of political maturity in three generations of students who have revered the Iranian university system as a sort of Temple of Politics, and themselves as the sentinels of an ever-burning political conscience undimmed by the apathetic public and authoritarian leadership.

The Setup

Daftar Tahkim bands together "Islamic Associations" (student assemblies) at state universities across the country's 30 provinces into a single centralized union. Every year, each university student association holds elections to send representatives to the Tahkim union. The number of representatives each university sends depends on its size and its level of political activity. These 60 or so elected representatives meet once a year to vote on Tahkim's annual agenda and to elect nine members to serve a one-year term on the union's Central Council. The vote conditions are stringent: candidates must secure two-thirds of the total votes cast by the representatives (i.e., the "general assembly"). Central Council members each head a different committee tasked with running Takhim affairs, and collectively decide on the student union's official stance on political issues and academic affairs.

From regime's arm to regime's bane

When it was first established, Tahkim worked closely with the government, playing a central role in the seizure of the U.S. embassy in November 1979 as well as the crackdown on universities in 1980 that purged hundreds of dissident professors and students. But after the end of the war with Iraq, Tahkim began to adopt a critical slant toward the government, criticizing the economic policies of the Rafsanjani administration and the 'stifling' political climate at universities.

Pro-government vigilante groups, the regime's unofficial security apparatus, responded accordingly. On one occasion, when Dr. Abdolkarim Soroush, a prominent thinker popular among students and very unpopular with the regime, was due to give a lecture at Amir Kabir University, a vigilante group hung a noose from the university gateway, intended as a threat to dissuade Soroush from lecturing.

The turning point came when Daftar Tahkim effectively broke with the ideological right-wing during the 1997 presidential race, when the student union threw its weight behind moderate candidate Mohammad Khatami. The Islamic Association at Sharif University -- Iran's MIT -- hosted Khatami's first campaign rally. The event, attended by thousands of students, "exploded like a bomb among the student population," recalls a former Tahkim member, propelling Khatami's meteoric rise in landing the youth vote that year. As the student movement was galvanized by the advent of the Reformist movement, the student union entered a newly empowered phase with a clear mandate: to push for reforms in the executive branch of government.

Tahkim under Khatami

"Daftar Takhim effectively functioned in the capacity of a political front," says former Central Council member Ali Akbar Mousavi Khoeini, who went on to be elected as one of the youngest representative to the Reformist-dominated 6th Majlis. "Students were on the forefront of the struggle to create 'pressure from below' during the first term of Khatami's presidency," he adds, referring to Reformist strategist Saeed Hajjarian's tactic for enacting reform ('haggling at the top, pressure from below').

Tahkim had private audiences with Khatami several times a year, and maintained close contact with his administration, especially the Ministry of Science and Ministry of Culture, to lobby for student demands. These demands included legislation for press freedom and free flow of information, and legislation to bring cartel-like financial institutes that operated outside of parliamentary oversight under Majlis supervision.

The list of demands grew following the deadly attacks on Tehran University dormitories in 1999, a tragedy known as Kuye Daneshgah. Tahkim issued a statement denouncing the vigilante group Ansar Hezbollah for the bloodshed, and called for a full investigation into the attacks and for prosecution of the offenders, as well as the release of student prisoners like Ahmad Batemi, who were arrested in connection with the student uprising that year. The student union also produced a film with footage and interviews documenting the events, copies of which were distributed widely on university campuses. Students were bitterly disappointed in Khatami's weak response to Kuye Daneshgah. They had expected that the perpetrators of the brutal murders would be brought to justice, but all Khatami did was verbally condemn the attack.

"Khatami should have used his political capital -- 20 million votes -- as leverage to push through his agenda for reform," says Mousavi-Khoeinha. "But he chose not to use this authority."

Yet Takhim did hold some degree of sway with the Reformist administration that their endorsement had helped elect to power. When Gholamhossein Karbaschi, the mayor of Tehran, was convicted on embezzlement charges, Takhim announced that students would march in the streets to demand his release from prison. The demonstrations did not take place because authorities released Karbaschi, in a move many saw as a concession to appease students. More importantly, Tahkim managed to send three of its members to Majlis.

Although the student union endorsed Khatami's reelection, the president's second term drew biting critiques from Tahkim, faulting his "weaker" cabinet that was focused on economic policies and notably less oriented toward political development and cultural progress. By the end of Khatami's tenure, Tahkim was so disenchanted by the failure of the eight-year Reform project that they issued a statement announcing they would abstain from voting in the 2005 elections.

And then came Ahmadinejad

Repression of the student movement accelerated under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as hardened disciplinary committees meted out harsh terms to student activists: academic suspension, expulsion, and sometimes, referral to the Revolution Court to stand trial. Student-run newspapers that had thrived and opened up public discourse during the so-called "Khatami Spring" were shut down one by one. State-sponsored financial resources, facilities, and licenses for events were also cut off.

Akbar Atri, a former member of the student union who was briefly detained in 2003 when officials seized Tahkim's office on Jomhouri Street in downtown Tehran, recalls that "the order was said to have come from the top, through the Supreme Leader's clerical representatives at the universities, who are stationed there as informants."

The student union began to increasingly rely on virtual networks to sustain its "consolidation," a connectivity once used to control students now used by the Iranian youth to keep grassroots democratic activism alive.

"During the Reformist period, civil institutions were allowed to develop and progress," says Mousavi-Khoeini. "People working within civil society learned about new methods of interaction." As high-speed Internet access became more prevalent, the union of student associations learned how to build web-based networks to "arrive at a balance of opinions on how to move forward and strategize... so that they don't have to see each other face-to-face to discuss opinions and make decisions."

As it turned out, Tahkim's role would pale as a central nexus and organizer of student activities when the structure of communication among Iran's four million students shifted to a decentralized network that allowed for organization on a local level as protests flared up on campuses across the country in the wake of the country's cataclysmic 2009 presidential election.

June elections and beyond...

A month before the election, Tahkim sent letters to all four candidates -- Mir Hossein Mousavi, Mehdi Karroubi, Mohsen Rezaei, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad -- listing a set of student demands to ascertain who would pledge to meet those demands if elected. Only Karroubi responded with a firm pledge; consequently, the student union issued a statement formally endorsing the Reformist cleric as their candidate of choice.

"Takhim's vote was completely demand-centered," Akbar Atri, the former student leader, said. The list of demands focused on students' rights to academic freedom and free expression, release of student prisoners, and a reversal of policies barring students from study.

Separately, Mousavi-Khoeini added: "The Central Council members looked at Karroubi's record when he was Majlis speaker, and decided that he had the backbone to take a stand for reintroducing reform. Tahkim backed him and directed its energy on bringing non-voters to the ballot box."

Following the post-election crackdown that stamped out the summer's massive street unrest, the student union released multiple statements denouncing what they termed the "coup government" as well as calling on students to demonstrate on campus when universities reopened in September.

Wave of arrests did not stop turnout on 16 Azar

Wave of arrests did not stop turnout on 16 Azar

In the week leading up to Student's Day in early December, two members of Daftar Tahkim's Central Council -- Abbas Hakimzadeh and Milad Assadi -- as well as dozens of general assembly members were arrested in a bid to discourage student protests on 16 Azar. But as former student organizer Akbar Atri explained, the wave of arrests failed to scare off the resolute students.

"Despite the fact that most of Tahkim's leaders have been imprisoned in the past six months or continually summoned to the Intelligence Ministry and Revolutionary Court, the body of the union within various universities is so empowered that in the absence of student leaders they are able to operate autonomously," he said. "The new network structure of the student movement means that every time some student leaders are detained, a fresh batch of organizers takes their place."

Speaking in a telephone interview, Ali Qolizadeh, a 25-year-old engineering graduate who was accepted to an MBA program at Tehran University but illegally barred from enrollment due to his record of activism in the Tahkim general assembly, explained that since the elections, students involved in the opposition Green Movement coordinate activities using new methods of organization.

"It is a horizontal not hierarchical model that is directed by collective leadership," Qolizadeh said. "Small groups of 20 or 30 students band together using social media and operate locally, for instance, distributing fliers door-to-door in their neighborhoods... It is because of the virtual nature of our organizing activities that the government does not have the power to suppress us. It is the key to our success."

Mousavi-Khoeini, who is in touch with student organizers in Iran, said the structure of Tahkim altered after the election. "They have turned to networking activities, so that decision-making is no longer taking place at a top level."

Copyright © 2009 Tehran Bureau

6 Comments

"decision-making is no longer taking place at a top level"

What exactly is there to decide? Whether to tear up a picture of Imam Khomeini? Or to stand up the next day at Tehran University holding up placards of Imam Khomeini? Are these the types of decisions being made by the student organizers? Is this the kind of "success" Ali Qolizadeh is referring to?

Pirouz / December 17, 2009 11:41 PMIts ironic your name is Pirouz since you cant see victory when it stares you in the face. Protests in 20 universities in Iran ... yes, its a failure -- for you and your kind.

Amir / December 18, 2009 3:17 AMIn the comments section of EVERY SINGLE ARTICLE I have ever read on this site, I have seen at least one comment by Pirouz always spinning the subject in textbook Islamic Republic fashion. I don't intend to make accusations, but the consistency and unifom propagandist nature of his comments makes me very suspicious that he may be being paid to this! Ordinary readers leave comments every now and again when they feel they have something interesting to add. Propagandists spin every story to fit the ideology that sustains them.

Cy / December 18, 2009 9:32 AMPirouz: You are so annoying sometimes. I can tell you are an intelligent person, but you are always so d*mn negative. Do you even really believe they tore the picture of Khomeini? Your comments are all over these articles. Start using some facts to back them up!

Annoyed by Pirouz / December 18, 2009 5:32 PM"What exactly is there to decide?"

well, precious pirous, guess that'd be deciding and designin step-by-step the downfall of mullahs

@ pirouz / December 18, 2009 7:10 PMI wanted to thank you for compiling such an amazing article. I believe non-Iranian readers will find it a great resource for getting familiar with Iran's student movement, as will Iranians not previously involved in such activities. Incidents taking place during the past 6 months have made so many of us become new voices for Iran, although some of us were not fully aware of the foundations of student movements during high school or university studies.

M / December 18, 2009 10:51 PM