'Not by Street Demonstrations Alone'

by IAN MORRISON

28 Mar 2010 22:165 Comments

An interview with Saeed Rahnema

An interview with Saeed Rahnema

Saeed Rahnema was active in the labor and left movement during the 1979 revolution in Iran. He was a founder and a member of the Executive Committee of the Union of Workers/Employees Councils of IDRO, the largest industrial conglomerate of Iran. He was a member of the Industrial Management Institute and served as an officer of UNDP. He is now a Professor of Political Science at York University in Toronto, Canada.

Ian Morrison: Since the recent election crisis there has been some talk among opposition circles about the role organized labor could play in a struggle for democracy in Iran, often in reference to the 1978 oil strike. You took part in the labor council movement during the collapse of Shah and are a sharp critic of that movement today. What could a contemporary democracy movement learn from that historical experience?

Saeed Rahnema: For the first part of your question I can say, as I have argued elsewhere, that there are lots of street protests and confrontations at this stage, but, as important as they are, none of these can really threaten the existence of the Islamic regime. The regime will be in serious trouble when workers and employees in the major industries and in social and government institutions start a strike as they did in the time of the Shah. Strikes are the most important aspect in my view. The regime will not change with street demonstrations alone.

As for the council movement, in the period leading to the revolution a new type of organization was created, which did not exist in earlier short-lived periods of the labor movement in Iran, called Workers and Employees Showras or councils. The major economic crisis in the late 1970s, along with the gradual erosion of the Shah's power, led to labor activism in most of the large factories. Workers began to demand a set of reforms, increased job security, improved job classifications, as well as wage demands. These led to the creation of strike committees in a growing number of factories. As the political crisis deepened, many owners in the private sector abandoned their factories and left the country; managers in the state-owned industries could not function either, leaving the large industries of Iran without leadership, and forcing the strike committees to take over the factories. Soon, under the influence of the left-leaning activists present in most of these committees, they took the name of council or showras. After the revolution, all major factories established their own showras.

How exactly did showras function? In your work you describe organizing showras in the Industrial Development and Renovation Organization of Iran (IDRO), which lacked an industry wide union with dues paying membership.

IDRO was the largest conglomerate of industries in Iran, which is still true today. During the revolution it comprised of over 110 factories with over 40,000 workers and employees. Some Industries had very old traditional factories from the time of Reza Shah in the 1930s, which produced sugar, textile, cement, bricks, etc., and there was also newer medium to heavy industries, such as machine tool industries, and tractor manufacturing. The IDRO, along with the Oil, Petrochemical, Copper,and Steel industries, were the sites of major councils and strikes, particularly the oil strike, which crippled the Shah's regime.

Like other people involved in the council movement, I had my own illusions. We thought that the Councils, as a form of workers' control, would be able to run the industries. What I argued later was that the councils were doomed to failure for a variety of reasons, one of which you mentioned. However, when the councils came into existence during the revolution, they were successful in toppling the Shah's regime. When Khomeini and the Islamists came into power they were not happy about the councils movement, although the new regime could not have had a revolution without them.

Why were they not happy? Because the councils were mostly formed by the Left as well as the Mojahedeen. The Mojahedeen-e Khalgh, an eclectic religious left organization, was very popular in Iran, along with a wide variety of Socialist Left organizations. Leftists were the dominate figures in the councils and the regime knew this. Although we all supported the new changes as well as Khomeini's back-to-work legislation, confrontations with the regime started from day one. The new regime's first strategy was to bring the councils under its own control, which they failed to do. After this, they started to establish 'Islamic Councils' in a growing number of institutions, using groups that they had already created in workplaces called 'Islamic Associations.' These Islamic Associations were similar to Arbeitsfronts in Nazi Germany and the Sampo in Japan during wartime fascist rule. These associations started to weaken the genuine councils.

When the hostage crisis takeover of the American Embassy in Tehran came, everyone was very excited because they thought it was an anti-imperialist move. In fact this was the most tragic turning point in the revolution. Khomeini's regime used this as a pretext to suppress all dissent. Yet all the councils supported the hostage takeover and organized a huge demonstration in front of the embassy.

Soon the Iran-Iraq war started. With these two crises the regime suppressed all political movements, along with the workers' councils. As the regime became more powerful, the 'Islamic Councils' eventually took over all the showras, and we were all expelled from the unions and our workplaces.

Before these events, councils were extremely powerful. On many occasions we refused to negotiate with the government and were often able to appoint new management. The new post-revolution CEO of the IDRO was a council member from our organization. Still suppression and a lack of democracy were major factors. One of our founding members and a great friend, Mahmoud Zakipour, was later executed by the regime. But, as I have said, the demise of the councils was also the result of internal weaknesses.

One of the weaknesses that you describe is the lack of power on the city, region and national levels. Showras had power inside the factories, but they were not linked to Soviet-type organizations, nor were they linked together through industrial unions. Can you explain this?

One of the main problems of the councils was structural. All of these were 'enterprise' or 'house' organizations in which each factory had its own unit with all workers and employees (none of them due-paying) considered as members. There where no industrial organizations that could connect individual units together. The types of unions we created, although they covered over 100 factories all across the country with actual central leadership, only served as an umbrella organization, itself isolated from other workers groups.

More importantly, the left was theoretically confused about councils. In regards to the analogy with the Russian Revolution, the councils in Iran were not like the Soviets that emerged in the 1905 and 1917 revolutions. Showras were not organs of political power which organized workers, soldiers and sailors at the city level. Neither were they similar to the Turin councils of the 1920s, which were organs of self-government. If you compare it with the Russian Revolutions, showras were more like factory committees.

The left considered Showras as organs of workers' control, but they were not in a position to exert control other than in a time of crisis and therefore only temporarily. Even if the councils had the capability to manage -- in some cases technically they could, because many engineers and middle managers had also joined the councils -- still the nature of Iranian industries would not allow for self-government because they were heavily reliant on government subsidies, and were also reliant on licensed imported parts and materials from multinational companies.

Can you explain the process through which these powerful councils were defeated?

The councils were weakened over the course of seven to eight months. Ironically, the confrontations between the councils started with the provisional government of Bazargan formed by the religious nationalist liberals. At that time the Islamists were not ready to run the government and were forced to rely on their closest allies, the religious nationalists. Councils created lots of problems for the liberal government, which was more tolerant of the councils than the Islamists after the provisional government resigned during the hostage crisis.

Internal ideological conflicts within councils were a major problem. Most of the leading members of the councils were members (or sympathizers) of different political organizations. The most powerful left organization of the time, and most influential in the council movement, was the Fadayeen. The Fadayeen had originated from a guerrilla organization during the time of the Shah and soon split into several different Fadaee groups. There was also the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party, Workers Path, and finally a multitude of Maoist organizations. The council members were trying to bring their political organizations' policies into the councils, despite that fact that all these groups were confused about the councils themselves, and had no understanding of democratic workers/employees organizations. The main demand for these groups was 'workers' control.' Yet it was never clear what was meant by this. Does workers control mean total control of production, management, and distribution, by workers alone? This was particularly problematic for large industries. Take for example the Oil industry, or the city transit services. If workers control these industries, what would be the role of the state? And, there are many other questions that I have discussed elsewhere.

After years of repression, and outright exploitations during the Shah's rule, workers had many demands. The old factories were totally impoverished. Even we, who had familiarity with Iranian industries, when during the revolution we started visiting different factories throughout the country (which produced textiles, jute, and other products), we were seriously shocked. It was very hard not to cry for the conditions of the workers and, of course, the workers wanted to solve all the problems overnight.

I remember that once I received a call from the head of a Jute factory in northern Iran. The manager of the factory, whose appointment we had supported, said that today the council unanimously decided to bring all the workers who had been laid off in the past 15 years back into the factory (1,000 workers). He said that the factory could barely manage with the current 900 workers, let alone adding 1,000 more. The Executive Committee of IDRO Union met, and we came to the very difficult choice of not supporting the Jute councils' decision. Problems such as this were endemic.

Overall, as a result of external factors such as repression, a lack of democracy, and internal structural factors, the councils were not in a position to manage the industries. What we needed to do was focus on establishing industrial unions, and turn the councils into their participatory arm in management. We needed to push for political democracy at the national level with industrial democracy on the shop-floor, then, as the unions become stronger one could push for higher levels of participation. There were no industrial unions under the rule of the Shah and we certainly do not have any now.

In the decades following the revolution the Iranian economy has been significantly 'privatized.' How would a more industrially inflected labor movement deal with the problem of international capital? How did this affect the Showras?

Iranian industries, first of all, were mostly government owned. I am referring to large manufacturing industries. However, the vast majority of Iranian industries are privately owned businesses with less than 10 workers. Immediately after the revolution the major industries of the private sector became nationalized and some were given to the religious foundations (bonyads). There were also about 900 top state-owned industries. These industries were mostly reliant on multinational corporations (at the time of the Shah there were some 250 multinationals operating in Iran). They were producing many brands of cars, and all sorts of durable consumer goods, but all of these were assembly plants with minimal local content which relied heavily on imported materials. These industries continue to be like this.

During the Iran-Iraq war, amazingly, in a turn towards war production, the economy was much more self-sufficient. But after that Iran has continued to be a major importer of raw materials. In the period after the Iran-Iraq war, when Hashemi Rafsanjani came to power in 1989, he followed a kind of neoliberal policy. In this period a new capitalist class was created from the ranks of clerics and senior Islamic Guards officers and their families. During this time a new middle class emerged along with a widening gap between the rich and poor. Some industries were 'privatized.' And although foreign direct investment by multinational remained limited, Iranian industries did continue limited expansion.

'Privatization' is not exactly how it sounds. These are actually transfers of government-owned industries to cronies of the regime, which has continued under the present government of Ahmadinejad. This is so obvious. There are many cases. In one case, which got lots of publicity, a top conservative cleric got a government bank loan to take over a major chain of profitable industries way below its market value for his son. Yet, not only has he not paid back his loan, he did not even pay back the government. This is so-called 'privatization.' Many of Ahmadinejad's friends became millionaires through this process, or by getting major oil/gas contracts. Overall, Ahmadinejad has not paid much attention to the manufacturing industry. He is following a crude populist policy of distributing oil wealth rather than investing in industries that are old, polluting, and need new investments in technology.

When I read articles about Iran today, there is a great deal of social unrest around economic issues, particularly workers not getting paid. There are many labor actions but not a labor movement per se. I wonder what kind of possibilities there are for economic issues becoming more of a question for the Green Movement?

There is now a major economic crisis in Iran. Massive unemployment, terrible inflation (close to 30%), and at the same time, as you rightly said, there are many factories that cannot pay their employees. In terms of leadership there is political anarchy. You have got government-owned industries and then you have partially state-owned industries under the control of bonyads or Islamic foundations. The most significant bonyad is the Foundation of the Oppressed and Disabled (Bonyad-e Mostazafan va Janfazan). These are industries which had belonged to the Shahs' family and the pre-revolution bourgeoisie. After the time of the Shah they were all transferred to this particular foundation, which is now run by people close to the Bazaar of Iran and the clerical establishment. The bonyads are so large and so important that they are responsible for 20% of the Iranian GDP, which is only a bit lower than the Oil sector. Bonyads are not under the control of the state and pay no taxes. It is an anarchic system with no serious protection for workers. Workers do not have a right to strike. They do not have unions and this is the main problem.

Many of these industries are heavily subsidized. But the government has decided to end some subsidies, along with the elimination of many gas, flour, and transportation subsides too. By ending subsidies, or having targeted subsidies, there will be more problems and more industrial actions. But these industrial actions -- and you rightly separate labor actions from a labor movement -- need labor unions. Labor unions are the most significant aspect of the rights of workers. Unions need democracy and political freedoms, a freedom of assembly and a free press. That is why the present movement within civil society is so significant for the labour movement.

This is something that tragically some so-called Leftists in the West do not understand. We read here and there, for example, James Petras among others, who support the brutal suppressive Islamic regime, and take a position against women, youth and the workers/employees of Iran who confront this regime. It is quite ironic that the formal site of the regime's news agency posted a translation of Petras' article accusing civil society activists of being agents of foreign imperialism.

What we need is continued weakening of the regime by street protests along with labor organizing. And, I think it is very important that we recognize that the Green Movement is part of a larger movement in Iranian civil society. The Green Movement is a very important part, but, it is not the whole picture. The Green movement is now closely identified with Mr. Mousavi. So far he has been on the side of the people and civil society. Everyone supports him. But what will happen? Will he make major concessions? That remains to be seen.

There is a lot of confusion about the character of the regime because of its populist rhetoric. I am wondering what effect this confusion has on the possibility of organizing a trade union movement in Iran?

From the beginning, there were many illusions about the regime. One section of the Left, seeking immediate socialist revolution, immaturely confronted the regime and was brutally eliminated during the revolution. Another section of the Iranian left supported the regime, under the illusion of its anti-imperialism, and undermined democracy by supporting or even in some cases collaborating with the regime. This section paid a heavy price as well. Now, ironically, some leftist in the west are making the same mistakes under the same illusions.

There are four major illusions about Iran. The first is that the regime is democratic because it has elections. Leaving aside election fraud, in Iran not everyone can run for Parliament or the Presidency because an unelected twelve-member religious body, the Guardian Council, decides who can be nominated. Also, the Supreme Leader, who has absolute power, is not accountable to anybody.

The second illusion is the Regimes' anti-Imperialism. Other than strong rhetoric against Israel and the U.S., the regime has done nothing that shows that they are anti-Imperialist. Actually on several occasions they whole-heartedly supported the Americans in Afghanistan and at times in Iraq. Anti-imperialism has a much deeper meaning and does not apply to a reactionary force which dreams of expanding influence beyond its borders. If that is anti-imperialism, then the better example is Osama Bin Laden.

The third illusion is that this is a government of the dispossessed. A lot can be said about this, but I will limit myself to two income inequality measurements. Currently the Gini coefficient is around 44 (the range is from zero to a hundred, with zero as the most equal and one hundred as the most unequal.) This is worse than Egypt, Algeria, Jordan, and many other countries, despite the enormous riches of Iran. Interestingly, this figure is not so different from the time of the Shah. The other measurement, the deciles distribution of the top 10% and lowest 10 % income groups, shows that the top deciles' per capita per day expenditure is about 17 times that of the lowest deciles. This figure is also quite similar to the pre-revolutionary period.

The fourth illusion is that the regime is based on a 'moral' Islamic economy and not a capitalist economy. This moral economy, as Petras calls it, is nothing but the most corrupt capitalist system that we could possibly imagine.

There are some nascent unions, such as the bus drivers, sugar cane workers at Haft Tapeh, as well as teachers. These groups have been asking for international solidarity for a long time now. I wonder why those groups have had such a difficult time developing support. Have the conversations among 'left' groups about anti-Imperialism blinded them to these small but very real organizing efforts?

No doubt. Some among the left in the West make the same mistakes that the Iranian left made during the revolution -- focusing on anti-imperialism and undermining and minimizing democracy and political freedoms. If the left really cares about the working class, how can this class improve its status without trade unions? How can trade unions exist and function without democracy and social and political freedoms? Another aspect that some leftists don't take into consideration is the significance of secularism and the dangers of a religious state, particularly, the manner in which such regimes impinge on the most basic private rights of the individual, particularly women. Even if the Islamic regime were anti-imperialist, no progressive individual could possibly condone the brutal suppression of workers, women, and youth, who want to get rid of an obscurantist authoritarian and corrupt regime. The underground workers groups and other activists within civil society need all the support they can get from progressive people outside Iran, and they despise those so-called leftists in the West who support Ahmadinejad and the Islamic regime.

Ian Morrison covers labor for Tehran Bureau.

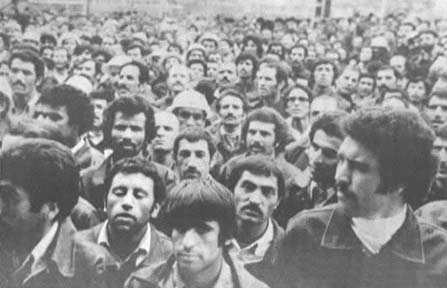

Photo: Oil workers strike.

Copyright © 2010 Tehran Bureau

5 Comments

Hello Mr. Morrison. You mentioned:

"The underground workers groups and other activists within civil society need all the support they can get from progressive people outside Iran, and they despise those so-called leftists in the West who support Ahmadinejad and the Islamic regime."

Please suggest specifically how progressive people outside Iran can support the underground workers groups without doing them harm. Thank you for any information.

Observer / March 29, 2010 1:27 AMPeople on the left or right outside Iran realistically cannot harm the Green Movement by expressing contempt for election fraud, human rights abuses,and random killings. They can support it (more than they think) by opposing blanket sanctions, military action and most important ,repeatedly ,emphasising the nature of the outrageous dictatorship in power there. The GM is not such a fragile bloom that foreign support or lack of, can kill it off. Were it so, it wouldn't have withstood the 9-month onslaught of the regime,which has been more dangerous than foreign activities or the antics of exiles or Israeli belligerence. BushJr. assembled his coalition of the 'willing' but there seems to be a coalition of the 'unwilling', unwilling to see that those who promote suffering wherever they may be should be viewed as enemies.

pirooz / March 29, 2010 7:24 AMSome of the political arguments between left and right need to be settled in the West. Is Bush and Cheneys TARP subsidy to Goldman Sachs, et al the Reaganite action of fiscal conservatives or the floundering of bumbling fools who sabotaged the US economy with their expensive wars? Is Obamas healthcare plan creeping communism or an investment in a healthier workforce that will make Buffet and co. even richer than they already are in the future? Was Clintons fiscally conservative achievement of balancing the budget the prelude to Bush and Cheneys liberal, spendthrift ways?Are the capitalist barons of the Peoples Republic of China ideological trojan horses? Will the Tea Party start picketing Walmarts? Is Neo-neoconservatism imminent? What happened to Newt Gingriches "Contract ON America"?

"The most significant bonyad is the Foundation of the Oppressed and Disabled (Bonyad-e Mostazafan va Janfazan). These are industries which had belonged to the Shahs' family and the pre-revolution bourgeoisie. After the time of the Shah they were all transferred to this particular foundation, which is now run by people close to the Bazaar of Iran and the clerical establishment."

"Transferred to the bonyad" - what a nice expression for brutal expropriation altogether with killing or chasing the owners from the country. Obviously all of them had stolen these industries!!!

As long as Mr. Rahnema and his likes continue to spread lies about their wonderful "revolution", nothing is going to change in their "Holy Republic"! khejalat ham khoub chiziyeh...

Arshama

Arshama / March 29, 2010 2:48 PMMany thanks Mr Morrison and Mr Rahnama for this brilliant interview. Stressing the crucial significance of independent trade unions for effective mobilisation, and pointing out the 'anti-imperialist', 'pro-poor' facade of this regime so naively hailed by some sections of the left in the West, will surely wash over the heads of socialists residing in cuckoo land, but will stay with us mortals who are concerned about human suffering and value lives and rights of human beings.

Mr Rahnama, if you read this, could you clarify your final point about support from those living outside of Iran. There are, as you know, many debates about the nature of this support. What framework do you have in mind for this support to remain legitimate and non-interventionist, that is, not becoming a tool for paving the path for sanctions and war, on behalf of the US and Israel, and not arrogantly aiming to direct the indigenous movement in Iran? Many thanks.

gorg O'meesh / March 29, 2010 2:51 PMTerrific interview!

Part of the problem (of support from the West) is that the Trade Unions in the US were smashed by Reagan and have only become weaker since then. Students lack intellectual political leadership.

SG / March 30, 2010 6:14 PM