Sex & Gender Analysis

Case Studies

Colorectal Cancer: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

The Challenge

Women have a higher risk than men of developing right-sided (proximal) colon cancer (Pal et al., 2010), which is associated with more aggressive forms of neoplasia compared to left-sided (distal) colon cancer (Hansen et al., 2012). Women are also prone to delayed diagnosis due to physiological and pathological differences in colon and colonic neoplasia, respectively. Despite sex- and gender-associated differences in nutrient metabolism and dietary practices, few studies have reported sex- and gender-specific risk estimates for dietary components.

Method: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Sex-related biological factors and gender-specific dietary choices influence segment-specific colon tumor formation. Collecting, reporting, and analyzing data by sex and gender is important for:

1. identifying genetic, anatomical, and physiological factors in men’s and women’s disease

2. applying an understanding of these factors when developing screening protocols

3. examining dietary factors and behaviors that influence cancer

Gendered Innovations:

1. Understanding Sex-Related Differences in Colorectal Cancer Risk may provide better prevention and treatment protocols for men and for women.

2. Providing Strategies for Sex- and Gender-Specific Screening Protocols may address issues associated with delays in colorectal cancer diagnosis.

3. Determining Gender-Specific Associations between Dietary Factors and Colorectal Cancer may lead to better cancer prevention guidelines.

Gendered Innovation 1: Understanding Sex-Related Differences in Colorectal Cancer Risk

Method: Analyzing Sex

Method: Analyzing Gender

Gendered Innovation 2: Providing Strategies for Sex- and Gender-Specific Screening Protocols

Method: Analyzing Factors Interacting with Sex and Gender

Gendered Innovation 3: Determining Gender-Specific Associations between Dietary Factors and Colorectal Cancer

Method: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Conclusions and Next Steps

The Challenge

The Global Health Observatory of the World Health Organization reported that 13% of all deaths originate from cancer. Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in the world, and it is one of the most common causes of cancer mortality in women followed by lung and breast cancer (Ferlay, 2013). Statistics from Korea and Japan indicate that colorectal cancer is the number one cause of cancer morbidity in women 65 years and older (Jung et al., 2012; Matsuda et al., 2014).

Dietary guidelines for cancer prevention represent an essential strategy to lower the burden of cancer. Despite sex- and gender-associated differences in dietary risk factors, few studies take these factors into account.

Gendered Innovation 1: Understanding Sex-Related Differences in Colorectal Cancer Risk

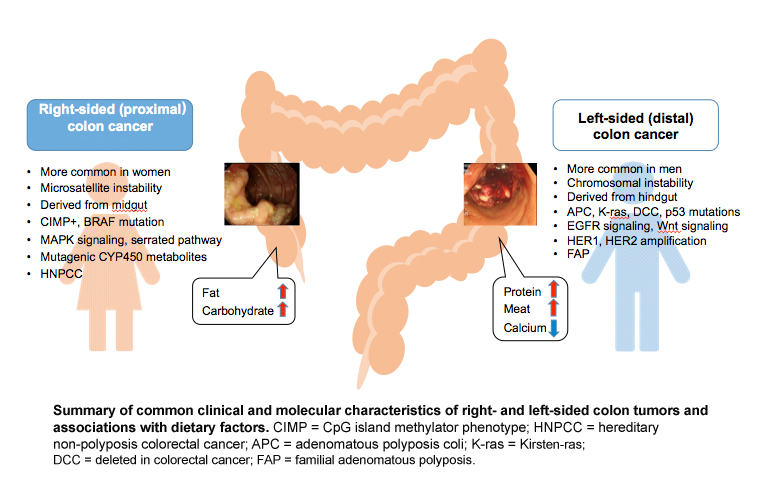

Women have a higher risk then men of developing right-sided (proximal) colon cancer (Pal et al., 2010), which is associated with poor prognosis. A major cohort study involving 17,641 patients compared right-sided colon cancer to left-sided colon cancer for clinical and histological characteristics, progress after the operation, and survival (Benedix et al., 2010). Proximal colon cancer is associated with more aggressive form of neoplasia compared to left-sided (distal) colon cancer (Hansen et al., 2012)—see Figure below. The results revealed worse outcomes for women, especially older women.

A recent cohort study has indicated that the risk of developing proximal large polyps as a proportion of all large polyps is higher in women. African Americans in the U.S. are more likely to develop proximal large polyps compared to whites and Hispanics (Lieberman et al., 2014). Although the effect of tumor location on survival remains uncertain, more information on pathophysiological differences in relation to sex is needed to plan strategies for screening and treatment of colorectal cancer.

Certain genetic and epigenetic differences between women and men may contribute to colorectal cancer risk. Microsatellite instability (MSI)-high, CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)-high, and BRAF mutation are often observed in right-sided colon cancer. By contrast, chromosomal instability, which is associated with 60-70% of colon cancer, is more often observed in left-sided colon cancer (Markowitz et al., 2009). Defective genes include APC, K-ras, DCC and p53.

CIMP-high was increased from the rectum to the cecum, with a higher percentage of females developing tumors in the cecum (Bae, J. M. et al., 2013). An earlier study reported that a methylated CpG island in the 5’ region of the p161NK4a tumor suppressor was positively associated with females (Wiencke et al., 1999). Another study showed that the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 936 polymorphism increased the risk of colon cancer in women only (Bae, S. J. et al., 2008). Also, the PIK3CA mutation occurs more frequently in females and in proximal colon cancer, which is associated with poorer survival (Phipps et al., 2013).

Method: Analyzing Sex

Differences in women and men’s patterns of colon cancer (discussed above) require understanding of sex-related biological factors that affect segment-specific colon tumor formation. Many of these factors can be studied in animal models. Animal studies, however, have preferred male animals. A literature search for experimental CRC studies using rodent models in Pubmed between 2012 and 2014 found 335 studies. Among those, 52% used only male animals, 18% used only female animals, and 30% used both sexes. More studies employing animals of both sexes are needed to investigate the molecular mechanisms of colon cancer development, responses to environmental stresses, and efficacy of treatments—and how these may differ by sex.

Method: Analyzing Gender

Women have been shown to be more strongly affected by cigarette smoking. Women who smoke exhibit a 19% increased risk of developing colorectal cancer compared to an 8% increased risk in men (Parajuli et al., 2013).

Gendered Innovation 2: Providing Strategies for Sex- and Gender-Specific Screening Protocols

Sex-specific anatomical and physiological characteristics have made it difficult to detect tumors during screening processes in women. A large cross-sectional study (n=4,910) found that in advanced colonic neoplasia, proximal colonic tumors (more common in women) are more often flat and depressed, while distal colonic tumors (more common in men) are polypoid and more easily detected by colonoscopy (Kaku et al., 2011). Endoscopic observations clearly revealed morphological difference between proximal versus distal neoplasia (see Figure below). Proximal colon cancer is more aggressive than distal and often at a more advanced stage when detected (Hansen et al., 2012). Women tend to exhibit polyps greater than 9mm while men exhibit smaller polyps upon colonoscopy (Lieberman et al., 2005), suggesting delays in diagnosis for women.

Moreover, women have longer transverse colon and increased redundancy compare to men (Saunders et al., 1996). The longer average total and transverse colon length and narrow colon diameter in women may lead to incomplete colonoscopy in women.

Other common colorectal cancer screening tools, such as the guaiac fecal occult blood test (FOBT), are less sensitive in women than in men (Brenner et al., 2010).

Taken together, these sex-specific aspects of colorectal cancer may explain women’s shorter 5-year survival rate and higher mortality in many regions of the world. Further, gender differences in health care revealed that among 1,071 surgical colon cancer patients, women (n=521, 48.6%) had less screening diagnosis (overall: 17.8% versus 22.6%; p=0.049) with subsequently higher rates of metastatic disease than men (Amri et al., 2014).

Method: Analyzing Factors Interacting with Sex and Gender

Colorectal cancer screening provides opportunities to prevent disease. The anatomical and physiological sex differences discussed above suggest that sex-specific screening tools and guidelines would enhance cancer detection.

- 1. Flexible sigmoidoscopy reportedly decreases examination pain in women (Farraye et al., 2004) and may lead to women seeking earlier screening.

- 2. A new spectroscopic applications of gastrointestinal endoscopy using early increase in rectal blood supply (EIBS) as a marker is shown to improve advanced proximal neoplasia detection (Roy et al., 2010). The performance characteristics of EIBS was superior in women indicating the use of EIBS as an adjunct to flexible sigmoidoscoopy may improve advanced tumor detection in women.

- 3. Women exhibit colorectal cancer about five years later than men; the cumulative 10-year incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer in women at ages 55, 60, and 65 follow rates in men at ages 50, 55 and 60 (Brenner et al., 2007). Colonoscopy is recommended for adults over 50 years old, yet there are no guideline regarding the age at which to stop colorectal cancer screening in many parts of the world. Asia-Pacific guideline stated that colorectal cancer screening should be continued until age 75 for both men and women (Sung et al., 2014). Due to longer life expectancy in women, colorectal cancer screening may need to be extended in women.

Gendered Innovation 3: Determining Gender-Specific Associations between Dietary Factors and Colorectal Cancer

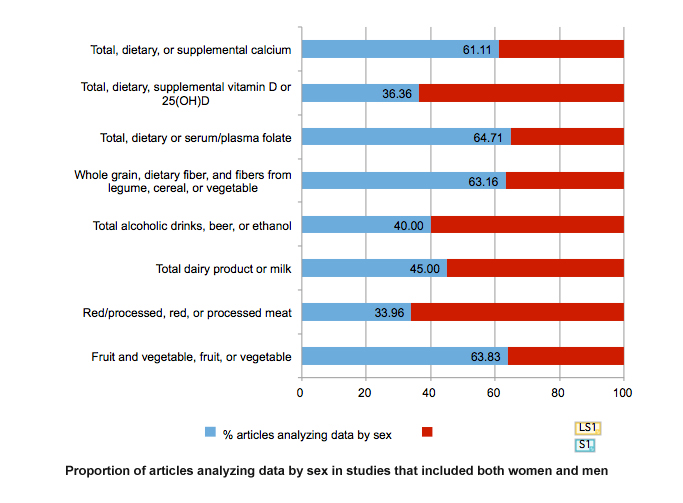

The Expert Report, “Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a global perspective” (World Cancer Research Fund et al., 2007) is the most comprehensive summary of the relationships between diet and cancer based on the analysis of over 7,000 scientific studies. The World Cancer Research Fund also provides the Continuous Update Project (World Cancer Research Fund et al., 2011). Among studies that included both men and women, the meta-analysis found that, while data was collected for women and men, and sex was reported, only half of the studies (51.02%) overall disaggregated data by sex. Only 33.96% of studies of red/processed, red, or processed meat and 64.71% studies of total, dietary and serum/plasma folate analyzed data by sex (see Chart below). The lack of sex-specific data impedes establishing dietary guidelines for cancer prevention that are valid for women and for men.

For alcoholic beverages, 40% of the studies reported sex-specific estimates. Given that sociological and cultural aspects of drinking vary by gender and that the toxic threshold of ethanol may differ by sex, providing data for women and for men will be important.

Since the 1980s, many female-specific prospective cohort studies (e.g. the Nurses’ Health Study, the Iowa Women's Health Study, the Black Women's Health Study, the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project Follow-up Cohort, the California Teachers Study, the New York University Women’s Health Study, the Shanghai Women's Health Study, and the Sweden Mammography Cohort) have analyzed the relationship between diet and cancer prevention. These studies have contributed to understanding cancer prevention for women, particularly for cancers that occur primarily in women. However, many other studies include both men and women and make a large contribution to the evidence for cancer prevention guidelines. Because these studies often reported sex-combined estimates, systematic review of sex-specific estimates often do not ensure a good statistical power and therefore dietary guidelines for cancer prevention have been limited.

Method: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Large population-based cohort studies should: 1) collect data for both women and men; 2) record sex; 3) analyze data by sex. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estimated a substantial increase to 19.3 million new cancer cases per year by 2025 (Ferlay et al., 2013). Given the biological and socio-cultural differences between women and men, sex- and gender-specific analyses should be conducted to provide optimal cancer prevention strategies and to reduce the number of new colorectal cancer cases both in men and women.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Specific sex (biological) and gender (environmental) factors influence the development of colorectal cancer, and cancer screening guidelines protocols need to address these factors.

Dietary factors that increase or decrease the risk of developing colorectal cancer are continuously updated based on large scale cohort studies. These studies need to collect, report, and analyze data by sex. Better data will lead to better guidelines for cancer preventive dietary habits.

1. Despite higher incidence of right-sided colon cancer in women, a substantially higher number of preclinical studies use only male animals. Researchers should be aware of sex-specific pathophysiological differences in colorectal cancer development and use both female and male animals appropriately in their research. These efforts can be supported by agencies providing research fund and editors of peer-reviewed journals when publishing research.

2. Sex-specific biological and anatomic characteristics of the colon, such as the longer average total and transverse colon length and narrow colon diameter in women, require consideration of sex when developing endoscopy devices.

3. Observational studies have reported the associations between dietary components and colorectal cancer risk. Diet is highly influenced by women and men’s consumption behaviors, and researcher should gather, report, and analyze data by sex and gender.

Works Cited

Amri, R., Stronks, K., Bordeianou, L. G., Sylla, P., & Berger, D. L. (2014). Gender and Ethnic Disparities in Colon Cancer Presentation and Outcomes in a U.S. Universal Health Care Setting. Journal of Surgical Oncology, 109(7), 645-651.

Bae, J. M., Kim, J. H., Cho, N. Y., Kim, T. Y., & Kang, G. H. (2013). Prognostic implication of the CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancers depends on tumour location. British Journal of Cancer, 109(4), 1004-1012.

Bae, S. J., Kim, J. W., Kang, H., Hwang, S. G., Oh, D., & Kim, N. K. (2008). Gender-specific association between polymorphism of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF 936 C>T) gene and colon cancer in Korea. Anticancer Research, 28(2B), 1271-1276.

Benedix, F., Kube, R., Meyer, F., Schmidt, U., Gastinger, I., Lippert, H., & Colon/Rectum Carcinomas Study, G. (2010). Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, 53(1), 57-64.

Brenner, H., Haug, U., & Hundt, S. (2010). Sex differences in performance of fecal occult blood testing. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 105(11), 2457-2464.

Brenner, H., Hoffmeister, M., Arndt, V., & Haug, U. (2007). Gender differences in colorectal cancer: implications for age at initiation of screening. British Journal of Cancer, 96(5), 828-831.

Farraye, F. A., Horton, K., Hersey, H., Trnka, Y., Heeren, T., & Provenzale, D. (2004). Screening flexible sigmoidoscopy using an upper endoscope is better tolerated by women. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 99(6), 1074-1080.

Ferlay J., Ervik M., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M., Parkin D., Forman D. & Bray, F. (2013). GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Retrieved 09-11, 2014, from http://globocan.iarc.fr

Hansen, I. O., & Jess, P. (2012). Possible better long-term survival in left versus right-sided colon cancer - a systematic review. Danish Medical Bulletin, 59(6), A4444.

Jung, K.W., Park, S., Kong, H.J., Won, Y.J., Lee, J.Y., Seo, H.G. & Lee, J.S. (2012). Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2009. Cancer Research and Treatment, 44(1): 11-24.

Kim, S.E., Paik, H. Y., Yoon, H., Lee, J.E., Kim, N., & Sung, M. K. (2015) Sex- and gender- specific disparities in colorectal cancer risk. World Journal of Gastroenterology, In press.

Lieberman, D. A., Holub, J., Eisen, G., Kraemer, D., & Morris, C. D. (2005). Prevalence of polyps greater than 9 mm in a consortium of diverse clinical practice settings in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3(8), 798-805.

Lieberman, D. A., Williams, J. L., Holub, J. L., Morris, C. D., Logan, J. R., Eisen, G. M., & Carney, P. (2014). Race, ethnicity, and sex affect risk for polyps >9 mm in average-risk individuals. Gastroenterology, 147(2), 351-358.

Markowitz, S. D., & Bertagnolli, M. M. (2009). Molecular origins of cancer: Molecular basis of colorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(25), 2449-2460.

Pal, S. K., & Hurria, A. (2010). Impact of age, sex, and comorbidity on cancer therapy and disease progression. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 28(26), 4086-4093.

Parajuli, R., Bjerkaas, E., Tverdal, A., Selmer, R., Le Marchand, L., Weiderpass, E., & Gram, I. T. (2013). The increased risk of colon cancer due to cigarette smoking may be greater in women than men. Cancer Epidemiolgy Biomarkers & Prevention, 22(5), 862-871.

Phipps, A. I., Makar, K. W., & Newcomb, P. A. (2013). Descriptive profile of PIK3CA-mutated colorectal cancer in postmenopausal women. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 28(12), 1637-1642.

Roy, H. K., Gomes, A. J., Ruderman, S., Bianchi, L. K., Goldberg, M. J., Stoyneva, V., Rogers, J. D., Turzhitsky, V., Kim, Y., Yen, E., Jamee,l M., Bogojevic, A., & Backman. (2010). Optical measurement of rectal microvasculature as an adjunct to flexible sigmoidosocopy: gender-specific implications. Cancer Prevention Research 3(7): 844-851.

Saunders, B. P., Fukumoto, M., Halligan, S., Jobling, C., Moussa, M. E., Bartram, C. I., & Williams, C. B. (1996). Why is colonoscopy more difficult in women? Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 43(2 Pt 1), 124-126.

Sung, J. J., Ng, S. C., Chan, F. K., Chiu, H. M., Kim, H. S., Matsuda, T., Ng, S. S., Lau, J. Y., Zheng, S., Adler, S., Reddy, N., Yeoh, K. G., Tsoi, K. K., Ching, J. Y., Kuipers, E. J., Rabeneck, L., Young, G. P., Steele, R. J., Lieberman, D., & Goh, K. L. (2014). An updated Asia Pacific Consensus Recommendations on colorectal cancer screening. Gut. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306503

Wiencke, J. K., Zheng, S., Lafuente, A., Lafuente, M. J., Grudzen, C., Wrensch, M. R., Miike, R., Ballesta, A., & Trias, M. (1999). Aberrant methylation of p16INK4a in anatomic and gender-specific subtypes of sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiolgy Biomarkers & Prevention, 8(6), 501-506.

World Cancer Research Fund, & American Institute for Cancer Research. (2007). Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research.

World Cancer Research Fund, & American Institute for Cancer Research. (2011). Continuous Update Project Report. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research.

Colorectal Cancer: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact In a Nutshell

Women are more likely than men to develop right-sided colon cancer, which is more aggressive than left-side colon cancer, the male-typical pattern (figure 1).

Right-side tumors are also flatter and harder to detect which means that women's cancers may go undetected.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Understanding sex-related differences in colorectal cancer risk may provide better prevention and treatment protocols for men and for women.2. Providing sex- and gender-specific screening protocols may improve diagnosis of colorectal cancer in women.

3. Determining gender-specific associations between dietary factors and colorectal cancer may lead to better cancer prevention guidelines.