Sex & Gender Analysis

Case Studies

Chronic Pain: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

The Challenge

Sex and gender affect all parts of the pain pathway, from signaling to perception to expression and treatment. Recent studies have shown that women generally display a lower pain threshold across all types of pain—pressure, heat, cold, chemical or electrical stimulation, and ischemia (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013; Mogil, 2012). Some researchers attribute these differences solely to biological (sex) differences; others suggest that these observed differences are, at least in part, diminished or amplified by gender. The fact that women and men are raised to express pain differently may modify both their biological response to pain and their willingness to report it (Samulowitz et al., 2018). A better understanding of biological (sex) and sociocultural (gender) mechanisms of pain, and how these interact with pain management regimes, may lead to better health outcomes for pain patients.

Methods: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Biological mechanisms, such as sex hormones, influence the nervous and immune systems and thus the signaling, perception, expression, and response to treatment of pain. Gender roles and norms also influence pain. Gender norms, which vary across cultures, impact a patient’s perceived sensitivity to pain. During childhood, boys may be taught to be tough and stoic and girls to verbalize discomfort (Samulowitz et al., 2018). Researchers have demonstrated that these gender norms can be changed and that this can impact perceived sensitivity to pain (Robinson et al., 2003). Thus, observed biological differences (sexual dimorphism) might also be a consequence of gendered social and environmental influences.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Female-Typical Bodies and Male-Typical Bodies Promotes Sex-Specific Treatment A better understanding of the influence of biological sex on the nervous and immune systems might help researchers design sex-tailored pain treatments.

2. Studying How Sex and Gender Interact, and How Sex and Sex Interact Men/boys, women/girls and gender-diverse individuals are socialized to respond differently to pain and this might influence their sensitivity to pain. Researchers’ sex might also influence a research subject’s response to pain.

3. Understanding How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain Gender stereotypes can influence how pain is experienced, a patient’s willingness to report pain, and how healthcare professionals manage pain.

The Challenge

Gendered Innovation 1: Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain

Gendered Innovation 2: Studying How Sex and Gender Interact, and How Sex and Sex Interact

Method: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Gendered Innovation 3: How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

Sex and gender affect all parts of the pain pathway, from signaling to perception to expression and treatment. Recent studies have shown that women generally display a lower pain threshold across all types of pain—pressure, heat, cold, chemical or electrical stimulation, and ischemia (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013; Mogil, 2012). Some researchers attribute these differences solely to biological (sex) differences; others suggest that these observed differences are, at least in part, diminished or amplified by gender. The fact that women and men are raised to express pain differently may modify both their biological response to pain and their willingness to report it (Samulowitz et al., 2018). This case study focuses on how sex and gender interact in pain.

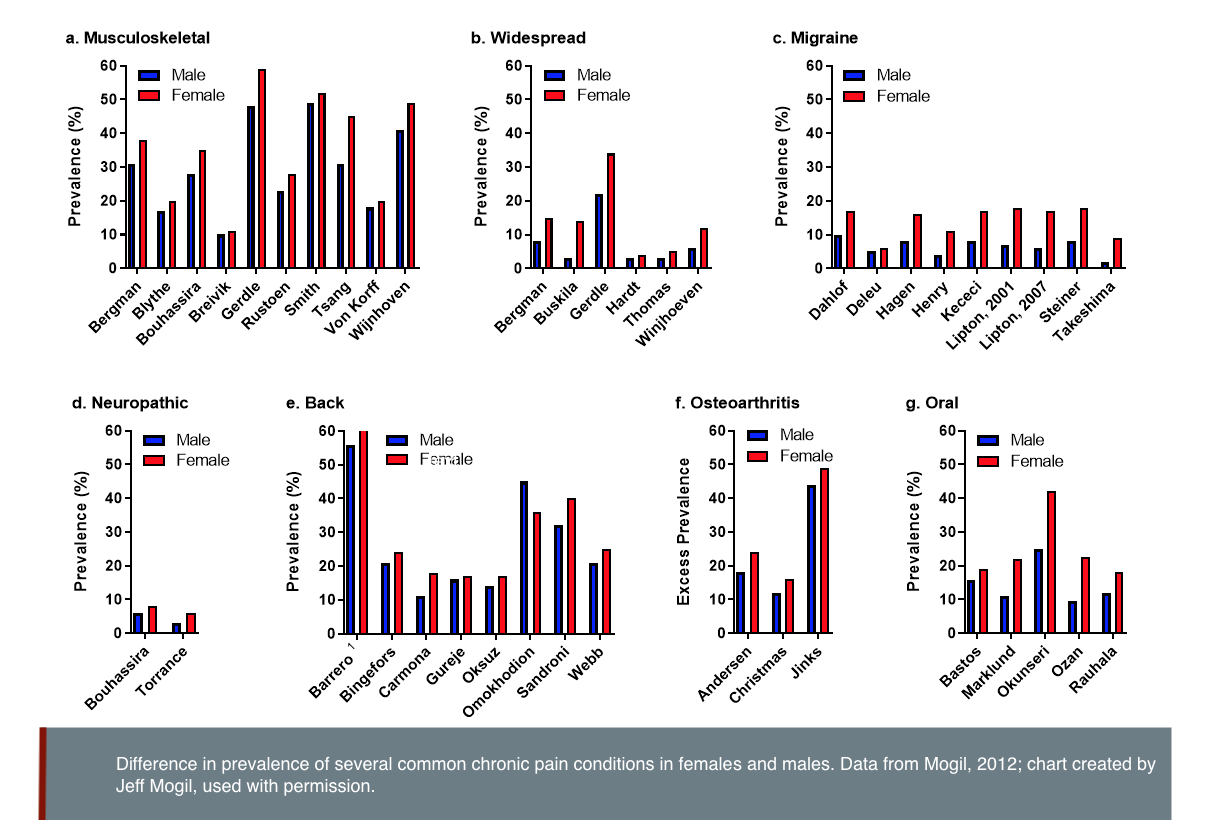

Chronic pain affects 20% of the adult population. Chronic pain refers to pain that persists past normal healing time and is commonly defined as pain that lasts more than 3 months (Merskey & Bogduk, 1994). Women, men and gender-diverse people all experience chronic pain. A higher prevalence of chronic pain has been reported in women compared to men (Greenspan et al., 2007; Mogil, 2012)—see figure below. Differences in the sources of pain also vary; migraine, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia are more prevalent in women, while cluster headaches are more prevalent in men (Sorge & Totsch, 2017).

Gendered Innovation 1: Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Female-Typical Bodies and Male-Typical Bodies May Promote Sex-Specific Treatment

The nervous system and the immune system are both involved in the development, maintenance and control of chronic pain. In experiments with male and female mice, injuries to peripheral nerves caused an increased sensitivity to pain. In females, T lymphocytes (white blood cells) mediated the response. In males, the response depended on central nervous system cells called microglia (which act as immune cells) instead. The researchers found that testosterone activates microglia and suppresses T cells, while estrogens activate T cells. While in both cases the result is increased sensitivity to pain, the pathways are different. In the future this could possibly lead to the development of female and male-specific painkillers (Sorge & Totsch, 2017). The researchers could also show that changing hormonal profiles throughout the lifespan influenced the pain pathway. Pregnant female mice, for example, switched to the male-typical pathway, while male mice that lacked testosterone switched to the female-typical pathway. If the results can be confirmed in humans, this could impact humans throughout their lifetime, and affect treatment choices in patients undergoing hormone therapy.

Additional mechanisms might influence pain perception in females and males. Animal studies have shown that the number of certain pain receptors is higher in female brains (Sorge & Totsch, 2017), while the descending pain control pathways—where the brain inhibits pain perception despite injury—activate more strongly in males (Sorge & Totsch, 2017).

Similar sex differences may influence human pain. In the European Union-funded Horizon 2020 project, NGN-PET (NGN-PET), researchers are modelling neuron-glia networks in an effort to discover new pain treatments. The role of both neurons and glial cells in chronic pain is well-documented but has not been exploited to develop novel specific painkillers that target neuronal-glial interactions. One objective of this project is to understand the specific mechanisms involved in common neuropathic diseases and whether these explain the higher susceptibility of women to neuropathic pain. This approach might lead to a better understanding of sex-specific pain mechanisms, help identify new targets for pain treatments, and improve pain treatments in a sex-specific manner.

Gendered Innovation 2: Studying How Sex and Gender Interact, and How Sex and Sex Interact

Sex and Gender Interact Pain perception and expression are influenced by many factors, for example social support, previous experience with pain, ethnicity and the concomitant presence of other diseases like depression. Gender stereotypes can also modulate pain perception. In a study of 120 men in Germany, two groups of men were enrolled and given opposite preliminary information. One group was told that men were less sensitive to pain than women because of their evolutionary role as hunters while the other group was told that women are less sensitive to pain because of the painful process of childbirth. The men in the first group reported less sensitivity to pain in the subsequent experiments. The associated imaging study (fMRI) suggests that this “gender priming” changed pain perception, and not just the willingness to report pain (Schwarz et al., 2019). More research in this area, including with gender-diverse people, is needed.

Sex and Sex Interact

Researcher’s sex can also influence response to pain. In animal studies, mice and rats exposed to painful stimuli displayed less discomfort when the experimenter was male compared to a female (Sorge et al., 2014). The phenomenon appears to be mediated by olfactory stimuli, i.e. the animals smell the pheromones of the experimenter. Male rodents experienced physiological stress when smelling other males (in this case humans), which dampened the intensity of the perceived pain. This phenomenon, which the authors label the “male observer effect,” seemed to be present in both male and female rodents, though it was more pronounced in female rodents.

The role of olfactory substances in the modulation of pain has also been reported in humans (Villemure & Bushnell, 2007). In one study, olfactory exposure to androstadienone (a male sexual steroid) improved mood in women but not in men. When women were exposed to a pain stimulus, androstadienone increased pain intensity which might be explained by a heightened attentional state produced by the exposure to steroid hormones. Unfortunately, the researchers did not report the gender identity or sexual orientation of the participants, which might impact the female and male reactions to androstadienone.

Method: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

In an EU-funded Horizon 2020 project, researchers are exploring factors and determinants for neuropathic pain, pain caused by damage to the nervous system (DOLORisk). The authors consider genetic, environmental/societal and clinical risk factors for neuropathic pain. By including gender and sex dimensions in both the genetic and environmental aspects of pain, the authors are increasing the chances of identifying vulnerable patients.

Gendered Innovation 3: How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain

Gender roles and identity influence how pain is experienced, patients’ readiness to report pain, and pain management by healthcare professionals.

Patient gender

Men may be less willing to report pain than women because dominant masculine gender roles associate male identity with toughness and stoicism (Robinson et al., 2001; Myers et al., 2003). Similarly, women are expected to report pain more readily. From childhood, girls and boys are frequently socialized to respond differently to pain and these attributes can vary across cultures and countries (Samulowitz et al., 2018). Researchers have demonstrated that these gender norms can be changed and that this can impact perceived sensitivity to pain (Robinson et al., 2003).

Gender assumptions in healthcare providers

Healthcare providers, who themselves embody gender identity, roles and relations, may treat their patients differently depending on their beliefs and subconscious assumptions. For example, some reports have shown that healthcare providers are more likely to classify pain as of psychological rather than physical origin in women compared to men (Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001). Men who suffer from chronic pain might find their “masculinity” questioned (Bernardes & Lima, 2010).

Pain might also be managed differently in women and men. Gender stereotypes may influence the treatments that physicians prescribe for women versus men reporting pain, and the choice of therapy in acute versus chronic settings. For example, in emergency medicine and prehospital settings, women with acute pain have been reported to obtain fewer painkillers, especially opioids (Lord et al., 2009), and wait longer than men for treatment (Chen et al., 2008). In these acute settings, women appeared to receive more non-specific diagnoses, be treated less aggressively, and prescribed more antidepressants than painkillers compared to men (Hamberg et al., 2002; Hirsh et al., 2013; Hirsh et al., 2014). Conversely, women with chronic pain are more likely to be prescribed opioids than men (Serdarevic et al., 2017; Simoni-Wastila, 2000). This places women at higher risk of developing dependency and overdosing on prescribed opioids than men (Green et al. 2009; Unick et al. 2013). Nevertheless, deadly overdoses are higher in men than in women (Calcaterra et al., 2013). This is in line with the fact that although women attempt suicide more than men, men more often die given their weapons of choice.

Women’s higher risk of opioid dependency may be due to differences in metabolism (sex) but also to experiences of trauma or distress (gender), which are more prevalent in women. Some women—including women who have experienced violence, Aboriginal and Indigenous women (in Canada), non-cisgender women and trans women—have been found to be at higher risk of opioid dependency (Hemsing et al., 2016).

The gender relations between provider and patient are complex. Researchers have found that women physicians were more likely to prescribe analgesics (painkillers) to patients in general and opioids to women patients, whereas men physicians were more likely to prescribe opioids to men patients (Safdar et al., 2009). In contrast, in an experimental study (as opposed to an observational one), Hirsh and colleagues found that women providers prescribed more antidepressants than men and offered more mental health referrals to women patients than to men (Hirsh et al., 2014). Women providers might be more inclined to consider psychosocial factors with women patients, which is in line with previous reports of the increased tendency of women physicians to discuss emotions and explore psychosocial factors (Roter, Hall, & Aoki, 2002). However, although emotional and psychological factors can contribute to chronic pain, women, men and gender-diverse patients alike should have equal access to both medication and mental health treatment.

Other sociocultural factors, including age, ethnicity and sexual orientation, can also influence pain treatments. In U.S. emergency rooms, for example, white people are 25% more likely to receive medication for acute pain than Hispanic people and 40% more likely than African American people (Hoffman et al., 2016).

Failing to consider how sex interacts with gender in pain may result in poor patient management and lead to chronic pain and patient decline. Gender-sensitive and possibly sex-specific pharmacological pain management is needed to improve patients’ outcomes and quality of life.

Conclusions

Both biological and sociocultural differences between women, men and gender-diverse people influence chronic pain at all stages from signaling to treatment. A better understanding of sex-specific neuronal and immune mechanisms in chronic pain might help researchers develop novel and more effective sex-specific treatments. Gender roles and behaviors influence pain expression by patients and treatment by healthcare providers. A better understanding of the influence of sex and gender on pain may improve the quality of care provided to patients, the control of their pain, and their overall quality of life.

Next Steps

1. Preclinical and clinical studies must integrate new findings on sex differences in pain pathways to develop new treatments tailored to patient sex.

2. More research on the interaction between gender and the biology of pain is needed. These studies should include women, men, gender-diverse and transgender people.

3. Understanding how gender roles and behaviors impact pain management needs to be taught to future healthcare providers. Everyone has a role to play in changing gender roles and behaviors, beginning in early childhood, by raising awareness in parents, families and educators.

Works Cited

Bartley, E. J., & Fillingim, R. B. (2013). Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111(1), 52-58. doi:10.1093/bja/aet127

Bernardes, S. F., & Lima, M. L. (2010). Being less of a man or less of a woman: perceptions of chronic pain patients' gender identities. The European Journal of Pain, 14(2), 194-199. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.04.009

Dance, A. (2019). The pain gap. Nature, 567, 448-450.

Calcaterra, S., Glanz, J., & Binswanger, I. A. (2013). National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999-2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(3), 263-270. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018

Chen, E. H., Shofer, F. S., Dean, A. J., Hollander, J. E., Baxt, W. G., Robey, J. L., . . . Mills, A. M. (2008). Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(5), 414-418. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00100.x

DOLORisk: understanding risk factors and determinants for neuropathic pain. Cordis. September 29, 2017. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/193238/factsheet/en.

Dragon, C. N., Guerino, P., Ewald, E., & Laffan, A. M. (2017). Transgender medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT Health, 4(6), 404-411. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0208

Fillingim, R. B., King, C. D., Ribeiro-Dasilva, M. C., Rahim-Williams, B., & Riley, J. L., 3rd. (2009). Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. The Journal of Pain, 10(5), 447-485. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001

Green, T. C., Grimes Serrano, J. M., Licari, A., Budman, S. H., & Butler, S. F. (2009). Women who abuse prescription opioids: findings from the Addiction Severity Index-Multimedia Version Connect prescription opioid database. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(1-2), 65-73. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.014

Greenspan, J. D., Craft, R. M., LeResche, L., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Berkley, K. J., Fillingim, R. B., . . . Pain, S. I. G. o. t. I. (2007). Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: a consensus report. Pain, 132 Suppl. 1, S26-45. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.014

Hamberg, K., Risberg, G., Johansson, E. E., & Westman, G. (2002). Gender bias in physicians' management of neck pain: a study of the answers in a Swedish national examination. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(7), 653-666. doi:10.1089/152460902760360595

Hemsing, N., Greaves, L., Poole, N., & Schmidt, R. (2016). Misuse of prescription opioid medication among women: a scoping review. Pain Research and Management, 2016, 1754195. doi:10.1155/2016/1754195

Hirsh, A. T., Hollingshead, N. A., Bair, M. J., Matthias, M. S., Wu, J., & Kroenke, K. (2013). The influence of patient's sex, race and depression on clinician pain treatment decisions. The European Journal of Pain, 17(10), 1569-1579. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00355.x

Hirsh, A. T., Hollingshead, N. A., Matthias, M. S., Bair, M. J., & Kroenke, K. (2014). The influence of patient sex, provider sex, and sexist attitudes on pain treatment decisions. The Journal of Pain, 15(5), 551-559. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.003

Hoffmann, D. E., & Tarzian, A. J. (2001). The girl who cried pain: a bias against women in the treatment of pain. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 29(1), 13-27.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296-4301.

Lord, B., Cui, J., & Kelly, A. M. (2009). The impact of patient sex on paramedic pain management in the prehospital setting. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 27(5), 525-529. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.04.003

Merskey, H., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Classification of chronic pain. 2nd edition. Seattle: IASP Press.

Mogil, J. S. (2012). Sex differences in pain and pain inhibition: multiple explanations of a controversial phenomenon. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(12), 859-866. doi:10.1038/nrn3360

Myers, C. D., Riley, J. L., 3rd, & Robinson, M. E. (2003). Psychosocial contributions to sex-correlated differences in pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 19(4), 225-232.

NGN-PET: Modeling Neuron-Glia Networks into a drug discovery platform for Pain Efficacious Treatments. Cordis. September 26, 2019. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/210123/factsheet/en

Robinson, M. E., Gagnon, C. M., Riley, J. L., 3rd, & Price, D. D. (2003). Altering gender role expectations: effects on pain tolerance, pain threshold, and pain ratings. The Journal of Pain, 4(5), 284-288.

Robinson, M. E., Riley, J. L., 3rd, Myers, C. D., Papas, R. K., Wise, E. A., Waxenberg, L. B., & Fillingim, R. B. (2001). Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to sex differences in pain. The Journal of Pain, 2(5), 251-257. doi:10.1054/jpai.2001.24551

Roter, D. L., Hall, J. A., & Aoki, Y. (2002). Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA, 288(6), 756-764. doi:10.1001/jama.288.6.756

Safdar, B., Heins, A., Homel, P., Miner, J., Neighbor, M., DeSandre, P., . . . Emergency Medicine Initiative Study, G. (2009). Impact of physician and patient gender on pain management in the emergency department--a multicenter study. Pain Medicine, 10(2), 364-372. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00524.x

Samulowitz, A., Gremyr, I., Eriksson, E., & Hensing, G. (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: a theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Research and Management, 2018. doi:10.1155/2018/6358624

Schwarz, K. A., Sprenger, C., Hidalgo, P., Pfister, R., Diekhof, E. K., & Buchel, C. (2019). How stereotypes affect pain. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 8626. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45044-y

Serdarevic, M., Striley, C. W., & Cottler, L. B. (2017). Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 238-246. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000337 Simoni-Wastila, L. (2000). The use of abusable prescription drugs: the role of gender. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 9(3), 289-297. doi:10.1089/152460900318470

Sorge, R. E., Mapplebeck, J. C., Rosen, S., Beggs, S., Taves, S., Alexander, J. K., . . . Mogil, J. S. (2015). Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nature Neuroscience, 18(8), 1081-1083. doi:10.1038/nn.4053

Sorge, R. E., Martin, L. J., Isbester, K. A., Sotocinal, S. G., Rosen, S., Tuttle, A. H., . . . Mogil, J. S. (2014). Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nature Methods, 11(6), 629-632. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2935

Sorge, R. E., & Totsch, S. K. (2017). Sex Differences in Pain. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(6), 1271-1281. doi:10.1002/jnr.23841

Unick, G. J., Rosenblum, D., Mars, S., & Ciccarone, D. (2013). Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993-2009. PLoS One, 8(2), e54496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054496

Villemure, C., & Bushnell, M. C. (2007). The effects of the steroid androstadienone and pleasant odorants on the mood and pain perception of men and women. European Journal of Pain, 11(2), 181-191. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.005

Women, men, and gender-diverse individuals perceive pain differently. They often express pain differently and may receive different treatments. A better understanding of sex and gender differences in pain may lead to better health outcomes.

Gendered innovations:

1. Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Women and Men Promotes Sex-Specific Treatment. A better understanding of the influence of biological sex on the nervous and immune systems might help researchers design sex-tailored pain treatments.

2. Studying How Sex and Gender Interact. Men/boys, women/girls, and gender-diverse individuals are socialized to respond differently to pain, and this might influence their sensitivity to pain. Men, for example, may be less willing to report pain than women because gender roles in Western cultures often associate male identity with toughness and stoicism.

3. Understanding How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain. Gender stereotypes can influence how pain is experienced, a patient’s willingness to report pain, and how healthcare professionals manage pain. For example, some healthcare providers are more likely to classify pain as psychological in women compared to men.