Dedicated to advancing scholarly and public understanding of the past, present, and future of western North America, the Center supports research, teaching, and reporting about western land and life in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Student Researchers Trace California's Coastal Act and the Agency it Spawned

The Big Sur coastline (Photo: Vadim Kurland via Flickr)

Imagine the state of California without its coastline: a thousand miles of sand dunes, forests, rocky inlets, marinas, muscle beaches, and coastal mountains. While the state's constitution enshrines coastal access as a right of every Californian, citizens looked seaward with alarm in the early 1970s as an oil spill fouled the waters off Santa Barbara and some extravagant development projects sought to bar the public from beloved beaches.

The result was the Coastal Act of 1972, a ballot measure passed with 52.5% of the vote, with strong support among Central and Southern counties along the coast. The Act led to the establishment of the California Coastal Commission, a public agency charged with protecting the coast, regulating development, and ensuring continued public access to a coastal zone extending three miles out to sea.

Its mandate placed the Coastal Commission at odds with powerful political and economic forces in California, and over the four decades since its establishment, its budget has been chipped away, its full-time staff declining nearly by half since 1980. “For some people, the Coastal Commission is their least favorite agency,” says Quito Tsui, a research assistant for the Bill Lane Center for the American West.

Four decades since the Coastal Act, how has a small agency fared at regulating development along a vast shoreline? Two groups of research assistants spent the summer of 2015 working for the Center's California Coastal Commission project to trace the origins of the agency, and assess the cumulative work done under its aegis.

Examining the Commission's Localized Implementation

One of the keys to the Commission's effectiveness may be a decentralized structure and reliance on localized implementation. The Commission is divided into six regional offices, these offices in turn look to local communities to produce their own development plans – with public comment and input.

The research assistants Elana Leone and Quito Tsui – advised by the Center's Iris Hui – sought to examine the Local Coastal Programs (LCPs) created by local municipalities and under the supervision of the Coastal Commission.

Leone and Tsui approached their survey with three principal questions:

- How did the Local Coastal Programs they studied align with the Coastal Act?

- What degree of influence does the Coastal Act have on these LCPs?

- How much autonomy does the LCP program give to local jurisdictions and their residents?

Elana Leone, left, and Quito Tsui

Tsui and Leone looked at seven Local Coastal Programs produced within two of the Coastal Commission's six zones: the North Central Coast zone running southward from Sonoma to San Francisco, and the Central Coast zone extending south from San Mateo to Monterey counties.

In their report, entitled “A Closer Look at Local Coastal Programs: A Case Study of the North Central Coast,” the authors explored the seven plans in depth, creating a matrix for point by point comparison, and mapped critical areas in each of the local communities, from wetlands to coastal structures, erosion hot spots, and areas threatened by sea level rise. Despite many commonalities, the program documents varied widely in length, scope, and issue focus.

Coastal Commission regions (enlarge)

“We found that despite the Coastal Act’s unquestionable influence on the LCPs in the North Central Coast,” write Leone and Tsui, “that each coastal jurisdiction has some flexibility in establishing its own priorities.” The authors noted, for example, that while Marin county was explicity devoted to protecting and supporting its coastal agriculture, the coastal plans for Daly City, Half Moon Bay and Pacifica were primarily concerned with urban issues like affordable housing and coastal access. This is understandable given the great difference in size and urban density between Marin and the latter urban areas.

But other differences were harder to reconcile: why, Leone and Tsui ask, did only some of the LCPs address bluff erosion and rising sea levels, when coastal hazards like these are felt equally among all of the communities they surveyed? In particular, they asked why San Francisco's LCP doesn't address flooding or flood prevention, given the number of residents in the coastal zone. “This lack of consistency across the board,” they write, “can have significant policy consequences given the seriousness of the threats dune erosion, bluff erosion and flooding pose to the North Central Coast.”

Despite the shortcomings of individual plans, Leone and Tsui conclude that the variation among the LCPs overall is a positive result of the Commission's decentralization of coastal management. "Despite the possibility of the Coastal Act whitewashing local areas and their unique characteristics," the authors write, "we instead found that the Coastal Act is in fact a malleable document that more often than not, works with local governments to create a document that protects the interests of both local areas and the coast."

When Seeking Water Savings, Increasing Agricultural Efficiency Could Backfire

Strawberries receiving drip irrigation on a Watsonville, CA farm during the summer of 2015. (USDA via Flickr)

This past spring, a New York Times editorial thundered against California farmers’ use of flood irrigation amid the state’s ongoing drought. The authors urged farmers to “switch from flood irrigation or inefficient sprinklers to drip or microspray systems, which use less water.”

According to the Center’s Vanessa Casado-Perez and Maggie Niu (’17), the Times’ editorials – and others like them – suffer from a flaw in conventional wisdom about agricultural water use during drought. Drip and microspray irrigation systems, while more efficient, often do not end up conserving water at all. Instead, says Niu, a research assistant for Casado-Perez during the summer of 2015, “efficient technologies like drip irrigation actually consume more water than older methods,” which generate return flows that can be reused by other farmers. Because drip and microspray systems deliver water directly to the crop in small quantities, the water is either entirely absorbed or lost to evaporation.

Maggie Niu, left, and Vanessa Casado-Pérez

As a result, Niu and Casado Perez write, “promotion of drip or sprinklers may backfire: they may divert less water and produce more in a single plot of land, but they may consume more water than flood, thus having negative systemic effects.”

Water Conservation Goals and Policies May Be Misaligned

Niu and Casado-Perez wondered if the mismatch between the stated goal – water conservation – and the technical solution – increasing efficiency – was one that affected the water policies of many western states, one that might limit their ability to achieve water conservation.

Research Surveys Western State Water Policies

For a forthcoming paper entitled “Agricultural Water Conservation Policies in the West,” the authors examined conservation regulations and legislative statutes in seventeen states from up in the Dakotas and Texas westward. Pointing out that the official definition of agricultural conservation is “reducing the amount of water used on farms,” they point out that “the reality is much more complex.”

In their paper they find that conservation programs vary widely. Many states mention conservation in their codes and water plans, but for several, like Idaho and Nevada, participation is strictly voluntary. By contrast, parts of Arizona have some of the most stringent conservation requirements. Conservation plans vary also in their scope – local, as in Texas, or statewide – and at whom the measures are aimed, whether individual farmers or entire irrigation districts.

Federal Program is Also Problematic

Niu and Casado-Perez also looked at the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), funded by the federal government and managed in partnership with the states. EQIP subsidizes farmers looking to switch to more efficient irrigation systems – generally drip irrigation. They found that while EQIP identifies its goal as natural resource conservation, nowhere does the text define what that means, nor how switching to efficient watering systems would bring real water savings. “EQIP,” they conclude, “takes for granted that the adoption of efficient irrigation systems will achieve the desired goal.”

Surface waterways and flood irrigation flow valves bring irrigation water to drought-affected Livingston, California in July 2015. (USDA via Flickr)

Finding Models in State Legislative Statutes

Failing to find evidence of robust conservation either in state codes or in a widely used federal program, the authors turned to state legislative statutes “aimed at solely promoting the conservation of water.” They found measures like these in four states they studied: Montana, Washington, California and Oregon.

Of these statutes, Niu and Casado-Perez conclude that California’s legal framework is the one that most clearly prioritizes reduced water consumption. Like the others, it incentivizes farmers to save water by granting them full or partial right to the water they conserve, which they can then lease or sell this water to another right holder. Additionally, however, California’s law is the only one that requires a net reduction in consumption for water rights holders to retain their right.

In summation, the authors say that states “should tailor legislation to fit the water supply and demand of their state, focusing on whether increased efficiency will bring them more benefits, even with the possibility of increasing consumption, or whether conserving water is their priority.”

But states should never assume that pursuing one goal will achieve the other.

Center Postdoc Finds a Home for Digital Scholarship

Bauch doing fieldwork in the Grand Canyon backcountry, September 2013 (Photo: Geoff McGhee)

The geographer Nicholas Bauch spent 2013-2015 as a postdoctoral scholar at the Center developing an online, interactive revival of a turn-of-the-century photographic slideshow of the Grand Canyon. His project has been acquired by Stanford University Press, and will become its first digital-only publication.

As I end my term as a postdoctoral scholar at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, already I can look back and recognize these two years as a period of tremendous professional and personal development. For those of us in the business of writing, thinking, reading, collaborating, and experimenting, there do not exist gifts of higher value than time and trust. Having been the recipient of these two irreplaceable gifts from the Center, I have built new ways of practicing the craft of knowledge production, certainly within my own discipline of geography, but also – relatedly – in the creative act of writing.

As I end my term as a postdoctoral scholar at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, already I can look back and recognize these two years as a period of tremendous professional and personal development. For those of us in the business of writing, thinking, reading, collaborating, and experimenting, there do not exist gifts of higher value than time and trust. Having been the recipient of these two irreplaceable gifts from the Center, I have built new ways of practicing the craft of knowledge production, certainly within my own discipline of geography, but also – relatedly – in the creative act of writing.

I started at the Center with a vision to make a digital scholarly publication based on a single historical document: the 1905 photographic slideshow of the Grand Canyon produced and sold by a career photographer named Henry Peabody. By the time I arrived in autumn 2013, the Center had already established a tradition of cutting-edge digital scholarship, led by the efforts of creative director Geoff McGhee, former postdoc Maria Santos, former Dee fellows Andy Robichaud and Cameron Blevins, and visiting graduate student Thomas Favre-Bulle, among others. As part of this cohort, I noticed that all of our work in digital media occupied an uneasy position with respect to the rigors of peer review and academic publishing. We were all doing high-quality work, yet blatantly missing was a pathway to the same accreditation achievable in traditional print media.

As my Grand Canyon project – called Enchanting the Desert – grew, the editors at Stanford University Press took notice, and invited me to submit a prospectus for the first born-digital monograph in their new digital scholarship publishing initiative. None of us knew exactly how to proceed; in fact, the template they first sent to me for the prospectus was taken nearly verbatim from their book proposal template. I happily spent an enormous amount of intellectual energy fitting the needs of a digital scholar into the norms of the publishing industry, forging a new template for how digital scholars and publishers can communicate standards and best practices with one another.

The user interface of Enchanting the Desert (Stanford University Press)

With digital media, for example, new forms of narrative – in this case spatial narrative – became imminently possible. It became clear that anonymous peer reviewers for the historical content of the work would be necessary, as expected. But rather unexpectedly, it also became clear that reviewers for the design of the user interface would be necessary since the content of the project does not unfold linearly. From this I have found that designing for navigation and access (a reader cannot simply flip through the pages of a digital project like she can a book) is one of the major new realms traditional publishing houses will need to enter as born-digital scholarship continues to grow.

With a publication date now within sight (planned for 2016), my work at the Center has put me in a position to be a leader in the methods of the digital humanities as well as in the subject of cultural geography. These are very practical types of professional coups, as my knowledge about the history of tourism and photographic vision at the Grand Canyon has increased immeasurably alongside my technical skills in digital publishing – including things like website design, web archiving, cartographic design, and the application of media theory. Enchanting the Desert has given me the opportunity to practice all of these in one big cauldron, stirring the elements together to make a unique geographical vision of, as the subtitle to the project suggests, “a pattern language for the production of visual space at the Grand Canyon.”

Bauch using his field manual to line up the vantage point of one of Peabody’s original slides. (Geoff McGhee)

Despite all these invaluable achievements, the skill I can say that I have sharpened the most as a scholar – and as a person – during my time at the Center has been writing. Although I came to the Center with a Ph.D. and a considerable amount of experience in academia, I still felt something of a cold distance between the topics I thought about and what I read in my community of scholarship. That is, I always felt like I was on the outside looking in at geography books and journal articles, understanding and respecting what I read, but not knowing how exactly to do it myself. I always found myself wondering, “How do people write these documents?”

Part of my experience in academia before coming to the Center included two years as a teaching fellow in Stanford’s Introduction to Humanities program, a series of writing-intensive courses for first-year undergraduates. There I thought a lot about writing, witnessed the writing process for hundreds of students, and advised those hundreds of students on how to make their writing clearer and more engaging. But it was not until these past two years at the Center that I can proudly say that above all I now consider myself more than a good writer, or a writing instructor, but a professional writer.

Video profile of Enchanting the Desert from the Stanford Humanities + Digital Tools series. (Geoff McGhee)

With the time and trust granted to me by the Bill Lane Center, I have developed a style particular to the aims of my research visions, and have, with the countless informal conversations in the Center’s halls, consciously trained myself how to express all those wordless ideas, thoughts, feelings, and intuitions that constantly flood our minds. I have grown to love the process of finding the right word, to love those moments sitting in front of a blank page not knowing what exactly will emerge, and to love spending far too long perfecting a single sentence. I am better than I ever have been at slowing down, capturing, and describing the mechanics of the mind, something that I will cherish and continue to improve upon for the rest of my life.

Enchanting the Desert is forthcoming from the Stanford University Press.

Read more about Digital Humanities publishing by Nicholas Bauch »

Investigation into Fracking and Air Pollution Wins 2015 Knight-Risser Prize

The Center for Public Integrity

“Big Oil, Bad Air: Fracking the Eagle Ford Shale of South Texas,” a joint reporting project by the Center for Public Integrity, InsideClimate News and The Weather Channel, has been named winner of the 2015 Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism. Also receiving a Special Citation was BuzzFeed News, for “Warehouse Empire,” a report about the impact of warehouse sprawl at the eastern edge of the Los Angeles Basin. The Knight-Risser Prize is co-administered by the Bill Lane Center for the American West and the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships at Stanford. It celebrates the best environmental reporting on the North American West — from Canada through the United States to Mexico.

A 20-month joint reporting project spanning three organizations, “Big Oil, Bad Air” explores the tension between cheap energy and air quality in one of the most active oil and gas fields in the United States. The stories focus on 20,000 square miles of Texas where thousands of production facilities, and waste dumped into open pits, release toxic chemicals into the air with virtually no regulatory oversight.

The core project team comprised reporters Jim Morris of the Center for Public Integrity and Lisa Song and David Hasemyer of InsideClimate News; and Susan White, former executive editor of InsideClimate News. Greg Gilderman, a producer with The Weather Channel joined the effort as a video partner.

The prize includes a cash award of $5,000, and the winner participates in the annual Knight-Risser Prize Symposium, which brings journalists, researchers, scholars and policy makers together with public audiences to explore new ways to ensure that sophisticated environmental reporting survives in the West. The symposium will be held at Stanford University in early 2016. More details and registration information will be available soon.

Read more at the Knight-Risser Prize for Western Environmental Journalism »

Water and Energy at Issue in Fifth State of the West Symposium

Photos: Steve Castillo

Two fundamental resources of the American West, water and energy, were the focus of the fifth annual State of the West Symposium held on November 12. Collaboratively organized by the Bill Lane Center for the American West and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), the half-day event took place at SIEPR's headquarters on the Stanford campus.

Assessing The Economic State of the West

The SIEPR fellow and Stanford public policy lecturer David Crane opened the symposium with a keynote talk (video) assessing the economic state of the American West. Crane noted that while energy dependent economies in North Dakota and Alaska have suffered from declining oil and gas prices, other western states like California, Nevada, Washington, and Oregon saw robust employment growth over the past year. Crane added that a number of western states are seeing tax revenues approach levels not seen since before the Great Recession; at the same time, he pointed out how spending priorities have changed since the economic crisis. For example, California now devotes a much smaller share of its budget to long-term investments like transportation, parks, and education, in favor of meeting the increasing demands of Medicaid, pension obligations, and prison costs.

Video: Economic State of the West

Water Markets a Solution to Scarcity?

The afternoon sessions convened distinguished panels on two issues of critical importance. First, a panel led by SIEPR director Mark G. Duggan explored the feasibility of water transfers and markets as a possible approach for addressing the western drought (video). Felicia Marcus, chair of California's State Water Resources Control Board and a veteran water regulator, lamented the difficulty of achieving productive dialogue on water when most players only see one part of the larger picture. Warning that climate change will be a "game-changer" for California water – in that rising temperatures will reduce the state's ability to use winter snowpack for water storage – Marcus urged an "all of the above" strategy employing conservation, increased efficiency, groundwater recharge, water recycling and desalination and, perhaps most controversially, new water storage projects. Marcus predicted that while "water is complicated, it's not impossible, and we are making progress," pointing to a legislature that has passed more water legislation in the past six years than "in the previous three decades."

Stanford economist Frank Wolak has been working on water pricing formulas to help public utilities replace revenue they are losing to water conservation. He spoke about the promise of water markets as a way of allocating water more efficiently – pointing to the example of electrical markets as a model, using an "independent system operator" to manage pricing and exchange of resources. In electricity, said Wolak, the transmission network takes bids and uses them to run a market that balances supply and demand in real time. The challenge, though, is getting back exactly what you put in, he said, and dealing with possible effects on ecosystems. But the gain would be worth it, Wolak continued, saying that the money that goes to pay for armies of water lawyers could instead go to a tariff that would fund local water transfers.

Both Marcus and Wolak saw the Australian millennium drought – which lasted from 1995 to 2007 and led to major policy changes – as a valuable lesson for western water policy. Wolak pointed out how Australian ecosystems were given their own water right and a seat at the negotiating table, while Marcus admired the communal spirit that negotiators have shown – "even though they fight, there's much more talk of 'we'” in Australia.

Video: Panel on Water Markets

Debating the Costs and Benefits of a "Fossil Highway" to Asia

The second panel of the afternoon featured a spirited debate between opponents and supporters of fossil-fuel export facilities on the West coast (video). Moderated by Bruce E. Cain, the Spence and Cleone Eccles Family Director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West, the panel was led off by Sally Benson, co-director of Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy. Benson pointed out the growing share that renewable energy sources are taking in western states like California.

The conservation lawyer Jay Manning touted the successes of the Pacific coast states from California to British Columbia in promoting renewable energy policies, from cap and trade in California to carbon taxes in B.C. "These states, which together comprise the fifth largest economy in the world," Manning said, "will be the first to embrace the clean energy economy." At the same time that states like Oregon and Washington appear headed toward economy-wide limits on carbon, Manning warned of the possible effects of several fossil energy export projects proposed for ports in Washington and British Columbia. Focusing on the Millennium coal terminal proposed in Longview, Wash., Manning argued that sending U.S. coal abroad to be burned in Asia would add a billion tons of CO2 to the atmosphere every year.

Arguing the "pro" case for the terminals fell to Bill Chapman, CEO of the Longview-based Millennium Bulk Terminals company. Chapman countered that "having a dialogue about symbolic gestures in a mostly hydro-powered region is not going to affect China" – adding that China already has 155 coal-burning plants under development and that the policy priorities should be for Asian markets to burn cleaner coal – like the US's. He added that a priority is for Chinese plants to start using pollution control devices, which they have already installed but are reluctant to use because of the corresponding reduction in energy output.

Video: Panel on Energy Infrastructure

Evening Keynote with Wyoming Political Royalty

The Western Governor's Association chairman and Wyoming Governor Matt Mead gave the evening keynote address(video). Echoing the discussion of fossil fuel exports, Mead pointed out that his coal-rich state is the third largest energy exporter in the world, and that "it is unrealistic to think that the source of 40% of electricity is not going to be around," but added "it is the responsibility of coal-producing states to make it better."

Turning an eye to renewables, Gov. Mead said "we intend to build the world's best onshore wind platform, though delivering to California is problematic."

Gov. Mead also stressed the importance of ensuring that the West can meet the food needs of the future, despite the shrinking number of young people going into agriculture. He added that food is an important national security concern: "imagine the leverage of other countries if we needed them not just for fuel, but for food?"

From left to right: David M. Kennedy, Former Sen. Alan Simpson, Bruce E. Cain, Jody Foster, Nancy Pfund

Gov. Mead, the grandson of Wyoming Governor and Senator Clifford Hansen, was given a folksy introduction by his fellow Equality State political scion, the voluble former Senator Alan Simpson, the son of Wyoming Senator and Governor Milward Simpson. The address was followed by a conversation among Gov. Mead, Sen. Simpson, and Bill Lane Center founding former co-director David M. Kennedy.

In reaching back to his family roots, Gov. Mead emphasized the need for maintaining collegiality in working with the other western governors. "In Wyoming, civility matters. If you look at myself, Governor Brown and Governor Inslee [of Washington], we have fundamental disagreements on coal, but we have to work together on forest health and issues that don't recognize state boundaries. The Western Governors' Association and the ability to recognize differences and common interests, that's a model to me," he added.

Video: Gov. Matt Mead and Former Senator Alan Simpson

State of the West Symposium Returns in 2016

The sixth annual State of the West Symposium will be held in December 1, 2016. Complete video of this year's sessions is available at siepr.stanford.edu. Read about previous symposia on our State of the West page.

Watch complete video of the 2015 State of the West Symposium »

Applications Now Open for Summer 2016 Local Governance Institute at Stanford

Applications are now open for the 2016 Local Governance Summer Institute, taking place from July 24-29, 2016. This week-long summer institute at Stanford University is open to city managers, county executives, regional directors, and other senior local government officials from throughout the West.

Applications are now open for the 2016 Local Governance Summer Institute, taking place from July 24-29, 2016. This week-long summer institute at Stanford University is open to city managers, county executives, regional directors, and other senior local government officials from throughout the West.

See the event page for details and a link to the application form »

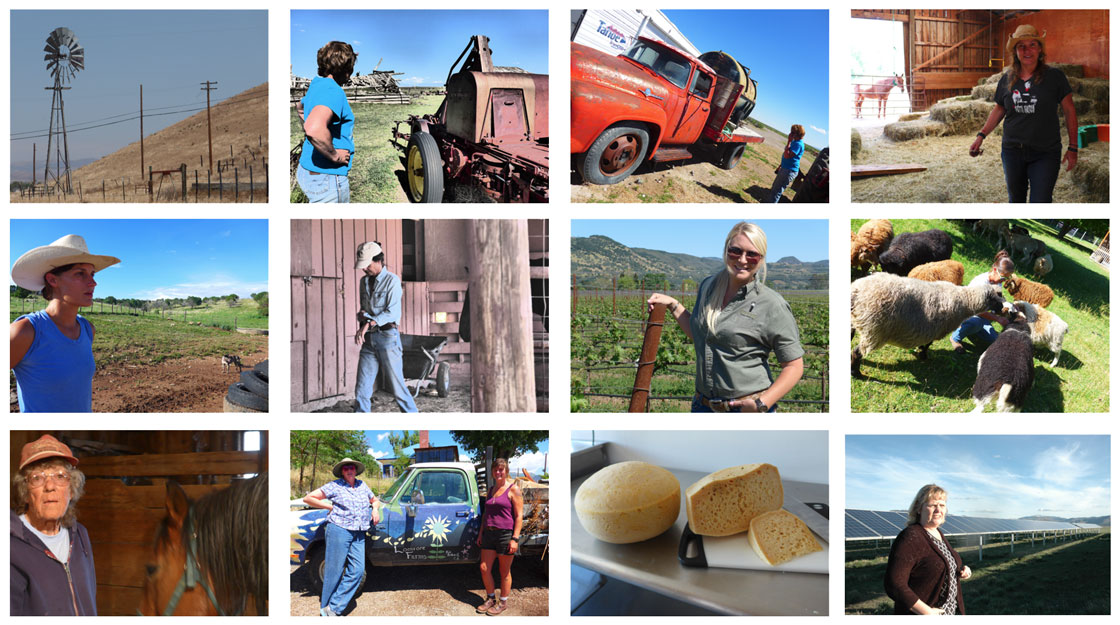

A Multi-Faceted Portrait of Women Farmers and Ranchers

Photographs from the Femme Farmer Project by Elizabeth Zach

Elizabeth Zach's story opens in a bar in Highwood, Montana, where the 76-year-old rancher Donna Schroeder points out two cattle brands carved into a wooden block. The first she shared with her husband, she says, the other she adopted after his death more than four decades ago – over which time she continued to run herds of 350-odd cattle on her own.

Zach, writing under a Western Journalism and Media Fellowship from the Bill Lane Center for the American West, continues,

Donna is a striking example of an intriguing and expansive demographic in America today. According to the Economic Research Service, a U.S. Department of Agriculture agency, in the past three decades the number of women-operated farms has increased substantially in the nation. Between 1978 and 2007, when the last agriculture census was completed, the number of women-operated farms in the U.S. grew from 306,200 to nearly a million. Women run 13 percent of all the nation’s farms and are 30 percent of all farmers in the U.S.

Since this past January, Zach has been traveling throughout the rural West interviewing women farmers and ranchers about their lives and livelihoods, compiling a moving portrait of a changing field though interviews with more than 50 subjects. Zach writes that the women she encountered ranged widely in age, background, and agricultural products, ranging from cattle ranchers to wine and artisinal cheese makers, from sheep herders to lavender growers.

One of Zach's most memorable subjects, a Colorado convent where nuns rise at dawn to tend cattle, gather eggs, make cheese and run a working farm, was just featured in the October 26 issue of High Country News. Zach, a prolific freelance journalist with bylines in The New York Times, the Washington Post and other publications, is also a staff writer for the Rural Community Assistance Corporation in Sacramento. The RCAC has published a long-form version of Zach's reporting on its newly relaunched website, and Zach is working with the Center to develop more outlets for her continuing reporting on the topic, including the Spence and Cleone Eccles Rural West Conference taking place next March in Missoula, Montana.

Read more at the Femme Farmer Project, the RCAC and High Country News »

New Faces and New Roles at the Center

From left, Iris Hui, Jessica Dutro, and Preeti Hehmeyer.

After some sad goodbyes over the summer, the Bill Lane Center for the American West entered the new academic year with some great new colleagues and a new look to our organizational structure. We hope you'll join us in welcoming our new coworkers, and making note of some changed responsibilities.

In August, Preeti Hehmeyer joined us as our new Associate Director, Planning and Development. Preeti got off to a busy start with the Center, flying down to Mexico at the end of her first week for our California-Mexico Clean Tech Trade Mission in Mexico City and Monterrey. Fresh from the world of management consulting, Preeti will be responsible for planning and organizing our events and conferences, as well as development and donor relations. She will also be handling our summer internships program and Sophomore Colleges.

Jessica Dutro is our new Associate Director of Finance & Administration. Jessica joined us from the university controller's office at the beginning of September, and has already showed her mettle by handling the many moving parts of a Sophomore College course that sent students and their instructors all around California, and our three US-Mexico collaborations on entrepreneurship, energy and water, and clean technology.

The researcher and social scientist Iris Hui is now our Associate Director, Academic Affairs. As a postdoctoral scholar, Iris had been running our American West scholars group for the past two years, and her responsibilities have now expanded to include oversight of all of our research projects, as well as our postdocs and dissertation scholars. We are excited to have Iris in this new role.

We'd also like to wish Kathy Montgomery well with her move to Oregon and to offer heartfelt thanks for her hard work, good humor, and friendship these past three years.

Native Lands and the Northwestern Boom: John Dougherty's Book Heads to Print

The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River in 1973. (David Falconer, National Archive via Flickr Commons)

We are very pleased to announce that John J. Dougherty's book Flooded by Progress has been acquired by the University of Washington and is headed for publication as part of the Emil and Kathleen Sick Book Series in Western History and Biography. According to the publisher, the series "features scholarly books on the peoples and issues that have defined and shaped the American West." and "seeks to deepen and expand our understanding of the American West as a region and its role in the making of the United States and the modern world." Previous titles in this prestigious series include works written and/or edited by Richard White, Katrine Barber, Andrew H. Fisher, Lissa Wadewitz (a former Center scholar), John Findlay, Alexandra Harmon, Jen Corrine Brown and others.

We are very pleased to announce that John J. Dougherty's book Flooded by Progress has been acquired by the University of Washington and is headed for publication as part of the Emil and Kathleen Sick Book Series in Western History and Biography. According to the publisher, the series "features scholarly books on the peoples and issues that have defined and shaped the American West." and "seeks to deepen and expand our understanding of the American West as a region and its role in the making of the United States and the modern world." Previous titles in this prestigious series include works written and/or edited by Richard White, Katrine Barber, Andrew H. Fisher, Lissa Wadewitz (a former Center scholar), John Findlay, Alexandra Harmon, Jen Corrine Brown and others.

John is in his second year as a postdoctoral fellow at the Center, and is working on completing his manuscript, which began as his doctoral dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley. Here, he describes his forthcoming book:

Flooded by Progress: Law, Natural Resources, and Native Rights in the Postwar Pacific Northwest examines the politics of federal Indian law and the changing environmental landscape in the post-World War II Pacific Northwest. It argues that the changing legal status of Native lands and resources was instrumental in both the industrial expansion of the region and environmental changes brought by increased development of natural resources. It highlights how the region’s environmental and economic transformations inequitably burdened Native communities in the Pacific Northwest, from their loss of treaty rights and tribal status to the destruction of tribal lands and natural resources. However, the book also illuminates how Native communities actively navigated critical directions in Indian policy and became powerful stakeholders in regional environmental politics.

Please join us in congratulating John and in looking forward to his book's debut.