Climate Science as Culture War

The public debate around climate change is no longer about science—it’s about values, culture, and ideology.

South Florida Earth First members protest outside the Platts Coal Properties and Investment Conference in West Palm Beach. (Photo by Bruce R. Bennett/Zum Press/Newscom)

In May 2009, a development officer at the University of Michigan asked me to meet with a potential donor—a former football player and now successful businessman who had an interest in environmental issues and business, my interdisciplinary area of expertise. The meeting began at 7 a.m., and while I was still nursing my first cup of coffee, the potential donor began the conversation with “I think the scientific review process is corrupt.” I asked what he thought of a university based on that system, and he said that he thought that the university was then corrupt, too. He went on to describe the science of climate change as a hoax, using all the familiar lines of attack—sunspots and solar flares, the unscientific and politically flawed consensus model, and the environmental benefits of carbon dioxide.

As we debated each point, he turned his attack on me, asking why I hated capitalism and why I wanted to destroy the economy by teaching environmental issues in a business school. Eventually, he asked if I knew why Earth Day was on April 22. I sighed as he explained, “Because it is Karl Marx’s birthday.” (I suspect he meant to say Vladimir Lenin, whose birthday is April 22, also Earth Day. This linkage has been made by some on the far right who believe that Earth Day is a communist plot, even though Lenin never promoted environmentalism and communism does not have a strong environmental legacy.)

I turned to the development officer and asked, “What’s our agenda here this morning?” The donor interrupted to say that he wanted to buy me a ticket to the Heartland Institute’s Fourth Annual Conference on Climate Change, the leading climate skeptics conference. I checked my calendar and, citing prior commitments, politely declined. The meeting soon ended.

I spent the morning trying to make sense of the encounter. At first, all I could see was a bait and switch; the donor had no interest in funding research in business and the environment, but instead wanted to criticize the effort. I dismissed him as an irrational zealot, but the meeting lingered in my mind. The more I thought about it, the more I began to see that he was speaking from a coherent and consistent worldview—one I did not agree with, but which was a coherent viewpoint nonetheless. Plus, he had come to evangelize me. The more I thought about it, the more I became eager to learn about where he was coming from, where I was coming from, and why our two worldviews clashed so strongly in the present social debate over climate science. Ironically, in his desire to challenge my research, he stimulated a new research stream, one that fit perfectly with my broader research agenda on social, institutional, and cultural change.

Scientific vs. Social Consensus

Today, there is no doubt that a scientific consensus exists on the issue of climate change. Scientists have documented that anthropogenic sources of greenhouse gases are leading to a buildup in the atmosphere, which leads to a general warming of the global climate and an alteration in the statistical distribution of localized weather patterns over long periods of time. This assessment is endorsed by a large body of scientific agencies—including every one of the national scientific agencies of the G8 + 5 countries—and by the vast majority of climatologists. The majority of research articles published in refereed scientific journals also support this scientific assessment. Both the US National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science use the word “consensus” when describing the state of climate science.

And yet a social consensus on climate change does not exist. Surveys show that the American public’s belief in the science of climate change has mostly declined over the past five years, with large percentages of the population remaining skeptical of the science. Belief declined from 71 percent to 57 percent between April 2008 and October 2009, according to an October 2009 Pew Research Center poll; more recently, belief rose to 62 percent, according to a February 2012 report by the National Survey of American Public Opinion on Climate Change. Such a significant number of dissenters tells us that we do not have a set of socially accepted beliefs on climate change—beliefs that emerge, not from individual preferences, but from societal norms; beliefs that represent those on the political left, right, and center as well as those whose cultural identifications are urban, rural, religious, agnostic, young, old, ethnic, or racial.

Why is this so? Why do such large numbers of Americans reject the consensus of the scientific community? With upwards of two-thirds of Americans not clearly understanding science or the scientific process and fewer able to pass even a basic scientific literacy test, according to a 2009 California Academy of Sciences survey, we are left to wonder: How do people interpret and validate the opinions of the scientific community? The answers to this question can be found, not from the physical sciences, but from the social science disciplines of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and others.

To understand the processes by which a social consensus can emerge on climate change, we must understand that people’s opinions on this and other complex scientific issues are based on their prior ideological preferences, personal experience, and values—all of which are heavily influenced by their referent groups and their individual psychology. Physical scientists may set the parameters for understanding the technical aspects of the climate debate, but they do not have the final word on whether society accepts or even understands their conclusions. The constituency that is relevant in the social debate goes beyond scientific experts. And the processes by which this constituency understands and assesses the science of climate change go far beyond its technical merits. We must acknowledge that the debate over climate change, like almost all environmental issues, is a debate over culture, worldviews, and ideology.

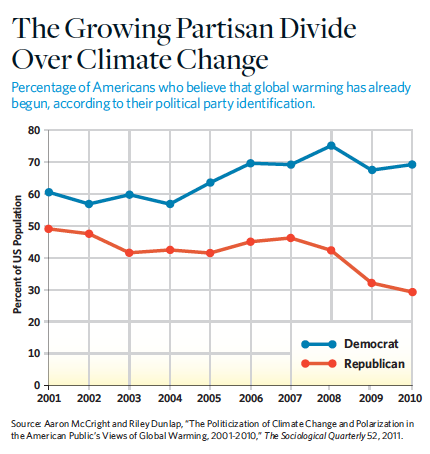

This fact can be seen most vividly in the growing partisan divide over the issue. Political affiliation is one of the strongest correlates with individual uncertainty about climate change, not scientific knowledge.1 The percentage of conservatives and Republicans who believe that the effects of global warming have already begun declined from roughly 50 percent in 2001 to about 30 percent in 2010, while the corresponding percentage for liberals and Democrats increased from roughly 60 percent in 2001 to about 70 percent in 2010.2 (See “The Growing Partisan Divide over Climate Change,” below.)

Climate change has become enmeshed in the so-called culture wars. Acceptance of the scientific consensus is now seen as an alignment with liberal views consistent with other “cultural” issues that divide the country (abortion, gun control, health care, and evolution). This partisan divide on climate change was not the case in the 1990s. It is a recent phenomenon, following in the wake of the 1997 Kyoto Treaty that threatened the material interests of powerful economic and political interests, particularly members of the fossil fuel industry.3 The great danger of a protracted partisan divide is that the debate will take the form of what I call a “logic schism,” a breakdown in debate in which opposing sides are talking about completely different cultural issues.4

This article seeks to delve into the climate change debate through the lens of the social sciences. I take this approach not because the physical sciences have become less relevant, but because we need to understand the social and psychological processes by which people receive and understand the science of global warming. I explain the cultural dimensions of the climate debate as it is currently configured, outline three possible paths by which the debate can progress, and describe specific techniques that can drive that debate toward broader consensus. This goal is imperative, for without a broader consensus on climate change in the United States, Americans and people around the globe will be unable to formulate effective social, political, and economic solutions to the changing circumstances of our planet.

Cultural Processing of Climate Science

When analyzing complex scientific information, people are “boundedly rational,” to use Nobel Memorial Prize economist Herbert Simon’s phrase; we are “cognitive misers,” according to UCLA psychologist Susan Fiske and Princeton University psychologist Shelley Taylor, with limited cognitive ability to fully investigate every issue we face. People everywhere employ ideological filters that reflect their identity, worldview, and belief systems. These filters are strongly influenced by group values, and we generally endorse the position that most directly reinforces the connection we have with others in our referent group—what Yale Law School professor Dan Kahan refers to as “cultural cognition.” In so doing, we cement our connection with our cultural groups and strengthen our definition of self. This tendency is driven by an innate desire to maintain a consistency in beliefs by giving greater weight to evidence and arguments that support preexisting beliefs, and by expending disproportionate energy trying to refute views or arguments that are contrary to those beliefs. Instead of investigating a complex issue, we often simply learn what our referent group believes and seek to integrate those beliefs with our own views.

Over time, these ideological filters become increasingly stable and resistant to change through multiple reinforcing mechanisms. First, we’ll consider evidence when it is accepted or, ideally, presented by a knowledgeable source from our cultural community; and we’ll dismiss information that is advocated by sources that represent groups whose values we reject. Second, we will selectively choose information sources that support our ideological position. For example, frequent viewers of Fox News are more likely to say that the Earth’s temperature has not been rising, that any temperature increase is not due to human activities, and that addressing climate change would have deleterious effects on the economy.5 One might expect the converse to be true of National Public Radio listeners. The result of this cultural processing and group cohesion dynamics leads to two overriding conclusions about the climate change debate.

First, climate change is not a “pollution” issue. Although the US Supreme Court decided in 2007 that greenhouse gases were legally an air pollutant, in a cultural sense, they are something far different. The reduction of greenhouse gases is not the same as the reduction of sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, or particulates. These forms of pollution are man-made, they are harmful, and they are the unintended waste products of industrial production. Ideally, we would like to eliminate their production through the mobilization of economic and technical resources. But the chief greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, is both man-made and natural. It is not inherently harmful; it is a natural part of the natural systems; and we do not desire to eliminate its production. It is not a toxic waste or a strictly technical problem to be solved. Rather, it is an endemic part of our society and who we are. To a large degree, it is a highly desirable output, as it correlates with our standard of living. Greenhouse gas emissions rise with a rise in a nation’s wealth, something all people want. To reduce carbon dioxide requires an alteration in nearly every facet of the economy, and therefore nearly every facet of our culture. To recognize greenhouse gases as a problem requires us to change a great deal about how we view the world and ourselves within it. And that leads to the second distinction.

Climate change is an existential challenge to our contemporary worldviews. The cultural challenge of climate change is enormous and threefold, each facet leading to the next. The first facet is that we have to think of a formerly benign, even beneficial, material in a new way—as a relative, not absolute, hazard. Only in an imbalanced concentration does it become problematic. But to understand and accept this, we need to conceive of the global ecosystem in a new way.

This challenge leads us to the second facet: Not only do we have to change our view of the ecosystem, but we also have to change our view of our place within it. Have we as a species grown to such numbers, and has our technology grown to such power, that we can alter and manage the ecosystem on a planetary scale? This is an enormous cultural question that alters our worldviews. As a result, some see the question and subsequent answer as intellectual and spiritual hubris, but others see it as self-evident.

If we answer this question in the affirmative, the third facet challenges us to consider new and perhaps unprecedented forms of global ethics and governance to address it. Climate change is the ultimate “commons problem,” as ecologist Garrett Hardin defined it, where every individual has an incentive to emit greenhouse gases to improve her standard of living, but the costs of this activity are borne by all. Unfortunately, the distribution of costs in this global issue is asymmetrical, with vulnerable populations in poor countries bearing the larger burden. So we need to rethink our ethics to keep pace with our technological abilities. Does mowing the lawn or driving a fuel-inefficient car in Ann Arbor, Mich., have ethical implications for the people living in low-lying areas of Bangladesh? If you accept anthropogenic climate change, then the answer to this question is yes, and we must develop global institutions to reflect that recognition. This is an issue of global ethics and governance on a scale that we have never seen, affecting virtually every economic activity on the globe and requiring the most complicated and intrusive global agreement ever negotiated.

Taken together, these three facets of our existential challenge illustrate the magnitude of the cultural debate that climate change provokes. Climate change challenges us to examine previously unexamined beliefs and worldviews. It acts as a flash point (albeit a massive one) for deeper cultural and ideological conflicts that lie at the root of many of our environmental problems, and it includes differing conceptions of science, economics, religion, psychology, media, development, and governance. It is a proxy for “deeper conflicts over alternative visions of the future and competing centers of authority in society,” as University of East Anglia climatologist Mike Hulme underscores in Why We Disagree About Climate Change. And, as such, it provokes a violent debate among cultural communities on one side who perceive their values to be threatened by change, and cultural communities on the other side who perceive their values to be threatened by the status quo.

Three Ways Forward

If the public debate over climate change is no longer about greenhouse gases and climate models, but about values, worldviews, and ideology, what form will this clash of ideologies take? I see three possible forms.

The Optimistic Form is where people do not have to change their values at all. In other words, the easiest way to eliminate the common problems of climate change is to develop technological solutions that do not require major alterations to our values, worldviews, or behavior: carbon-free renewable energy, carbon capture and sequestration technologies, geo-engineering, and others. Some see this as an unrealistic future. Others see it as the only way forward, because people become attached to their level of prosperity, feel entitled to keep it, and will not accept restraints or support government efforts to impose restraints.6 Government-led investment in alternative energy sources, therefore, becomes more acceptable than the enactment of regulations and taxes to reduce fossil fuel use.

The Pessimistic Form is where people fight to protect their values. This most dire outcome results in a logic schism, where opposing sides debate different issues, seek only information that supports their position and disconfirms the others’, and even go so far as to demonize the other. University of Colorado, Boulder, environmental scientist Roger Pielke in The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics describes the extreme of such schisms as “abortion politics,” where the two sides are debating completely different issues and “no amount of scientific information … can reconcile the different values.” Consider, for example, the recent decision by the Heartland Institute to post a billboard in Chicago comparing those who believe in climate change with the Unabomber. In reply, climate activist groups posted billboards attacking Heartland and its financial supporters. This attack-counterattack strategy is symptomatic of a broken public discourse over climate change.

The Consensus-Based Form involves a reasoned societal debate, focused on the full scope of technical and social dimensions of the problem and the feasibility and desirability of multiple solutions. It is this form to which scientists have the most to offer, playing the role of what Pielke calls the “honest broker”—a person who can “integrate scientific knowledge with stakeholder concerns to explore alternative possible courses of action.” Here, resolution is found through a focus on its underlying elements, moving away from positions (for example, climate change is or is not happening), and toward the underlying interests and values at play. How do we get there? Research in negotiation and dispute resolution can offer techniques for moving forward.

Techniques for a Consensus-Based Discussion

In seeking a social consensus on climate change, discussion must move beyond a strict focus on the technical aspects of the science to include its cultural underpinnings. Below are eight techniques for overcoming the ideological filters that underpin the social debate about climate change.

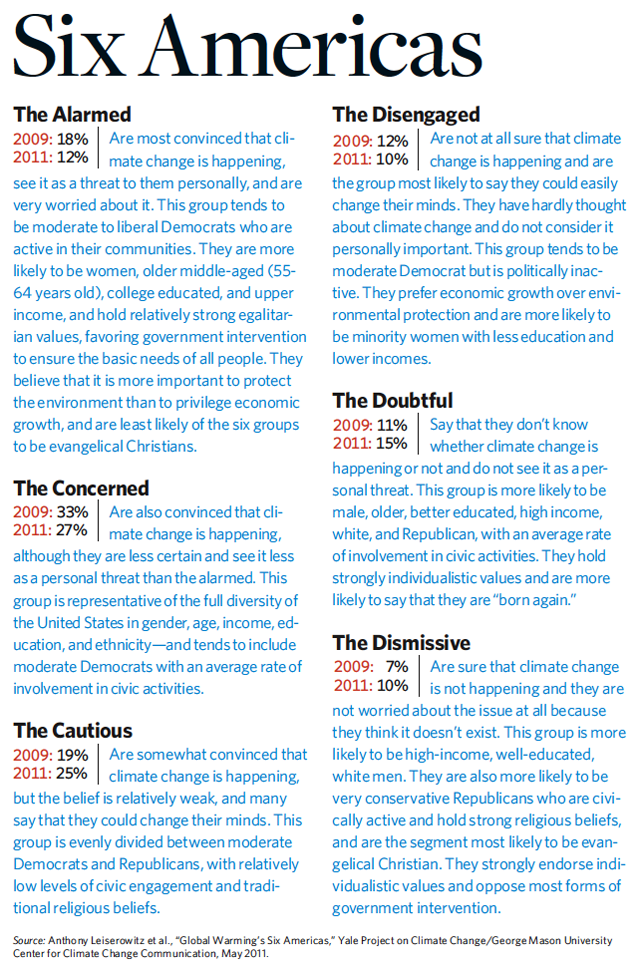

Know your audience | Any message on climate change must be framed in a way that fits with the cultural norms of the target audience. The 2011 study Climate Change in the American Mind segments the American public into six groups based on their views on climate change science. (See “Six Americas,” below.) On the two extremes are the climate change “alarmed” and “dismissive.” Consensus-based discussion is not likely open to these groups, as they are already employing logic schism tactics that are closed to debate or engagement. The polarity of these groups is well known: On the one side, climate change is a hoax, humans have no impact on the climate, and nothing is happening; on the other side, climate change is an imminent crisis that will devastate the Earth, and human activity explains all climate changes.

The challenge is to move the debate away from the loud minorities at the extremes and to engage the majority in the middle—the “concerned,” the “cautious,” the “disengaged,” and the “doubtful.” People in these groups are more open to consensus-based debate, and through direct engagement can be separated from the ideological extremes of their cultural community.

Ask the right scientific questions | For a consensus-based discussion, climate change science should be presented not as a binary yes or no question,7 but as a series of six questions. Some are scientific in nature, with associated levels of uncertainty and probability; others are matters of scientific judgment.

- Are greenhouse gas concentrations increasing in the atmosphere? Yes. This is a scientific question, based on rigorous data and measurements of atmospheric chemistry and science.

- Does this increase lead to a general warming of the planet? Yes. This is also a scientific question; the chemical mechanics of the greenhouse effect and “negative radiative forcing” are well established.

- Has climate changed over the past century? Yes. Global temperature increases have been rigorously measured through multiple techniques and strongly supported by multiple scientific analyses.In fact, as Yale University economist William Nordhaus wrote in the March 12, 2012, New York Times, “The finding that global temperatures are rising over the last century-plus is one of the most robust findings in climate science and statistics.”

- Are humans partially responsible for this increase? The answer to this question is a matter of scientific judgment. Increases in global mean temperatures have a very strong correlation with increases in man-made greenhouse gases since the Industrial Revolution. Although science cannot confirm causation, fingerprint analysis of multiple possible causes has been examined, and the only plausible explanation is that of human-induced temperature changes. Until a plausible alternative hypothesis is presented, this explanation prevails for the scientific community.

- Will the climate continue to change over the next century? Again, this question is a matter of scientific judgment. But given the answers to the previous four questions, it is reasonable to believe that continued increases in greenhouse gases will lead to continued changes in the climate.

- What will be the environmental and social impact of such change? This is the scientific question with the greatest uncertainty. The answer comprises a bell curve of possible outcomes and varying associated probabilities, from low to extreme impact. Uncertainty in this variation is due to limited current data on the Earth’s climate system, imperfect modeling of these physical processes, and the unpredictability of human actions that can both exacerbate or moderate the climate shifts. These uncertainties make predictions difficult and are an area in which much debate can take place. And yet the physical impacts of climate change are already becoming visible in ways that are consistent with scientific modeling, particularly in Greenland, the Arctic, the Antarctic, and low-lying islands.

In asking these questions, a central consideration is whether people recognize the level of scientific consensus associated with each one. In fact, studies have shown that people’s support for climate policies and action are linked to their perceptions about scientific agreement. Still, the belief that “most scientists think global warming is happening” declined from 47 percent to 39 percent among Americans between 2008 and 2011.8

Move beyond data and models | Climate skepticism is not a knowledge deficit issue. Michigan State University sociologist Aaron McCright and Oklahoma State University sociologist Riley Dunlap have observed that increased education and self-reported understanding of climate science have been shown to correlate with lower concern among conservatives and Republicans and greater concern among liberals and Democrats. Research also has found that once people have made up their minds on the science of the climate issue, providing continued scientific evidence actually makes them more resolute in resisting conclusions that are at variance with their cultural beliefs.9 One needs to recognize that reasoning is suffused with emotion and people often use reasoning to reach a predetermined end that fits their cultural worldviews. When people hear about climate change, they may, for example, hear an implicit criticism that their lifestyle is the cause of the issue or that they are morally deficient for not recognizing it. But emotion can be a useful ally; it can create the abiding commitments needed to sustain action on the difficult issue of climate change. To do this, people must be convinced that something can be done to address it; that the challenge is not too great nor are its impacts preordained. The key to engaging people in a consensus-driven debate about climate change is to confront the emotionality of the issue and then address the deeper ideological values that may be threatened to create this emotionality.

Focus on broker frames | People interpret information by fitting it to preexisting narratives or issue categories that mesh with their worldview. Therefore information must be presented in a form that fits those templates, using carefully researched metaphors, allusions, and examples that trigger a new way of thinking about the personal relevance of climate change. To be effective, climate communicators must use the language of the cultural community they are engaging. For a business audience, for example, one must use business terminology, such as net present value, return on investment, increased consumer demand, and rising raw material costs.

More generally, one can seek possible broker frames that move away from a pessimistic appeal to fear and instead focus on optimistic appeals that trigger the emotionality of a desired future. In addressing climate change, we are asking who we strive to be as a people, and what kind of world we want to leave our children. To gain buy-in, one can stress American know-how and our capacity to innovate, focusing on activities already under way by cities, citizens, and businesses.10

This approach frames climate change mitigation as a gain rather than a loss to specific cultural groups. Research has shown that climate skepticism can be caused by a motivational tendency to defend the status quo based on the prior assumption that any change will be painful. But by encouraging people to regard pro-environmental change as patriotic and consistent with protecting the status quo, it can be framed as a continuation rather than a departure from the past.

Specific broker frames can be used that engage the interests of both sides of the debate. For example, when US Secretary of Energy Steven Chu referred in November 2010 to advances in renewable energy technology in China as the United States’ “Sputnik moment,” he was framing climate change as a common threat to US scientific and economic competitiveness. When Pope Benedict XVI linked the threat of climate change with threats to life and dignity on New Year’s Day 2010, he was painting it as an issue of religious morality. When CNA’s Military Advisory Board, a group of elite retired US military officers, called climate change a “threat multiplier” in its 2006 report, it was using a national security frame. When the Lancet Commission pronounced climate change to be the biggest global health threat of the 21st century in a 2009 article, the organization was using a quality of life frame. And when the Center for American Progress, a progressive Washington, D.C., think tank, connected climate change to the conservation ideals of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Richard Nixon, they were framing the issue as consistent with Republican values.

One broker frame that deserves particular attention is the replacement of uncertainty or probability of climate change with the risk of climate change.11 People understand low probability, high consequence events and the need to address them. For example, they buy fire insurance for their homes even though the probability of a fire is low, because they understand that the financial consequence is too great. In the same way, climate change for some may be perceived as a low risk, high consequence event, so the prudent course of action is to obtain insurance in the form of both behavioral and technological change.

Recognize the power of language and terminology | Words have multiple meanings in different communities, and terms can trigger unintended reactions in a target audience. For example, one study has shown that Republicans were less likely to think that the phenomenon is real when it is referred to as “global warming” (44 percent) rather than “climate change” (60 percent), but Democrats were unaffected by the term (87 percent vs. 86 percent). So language matters: The partisan divide dropped from 43 percent under a “global warming” frame to 26 percent under a “climate change” frame.12

Other terms with multiple meanings include “climate denier,” which some use to refer to those who are not open to discussion on the issue, and others see as a thinly veiled and highly insulting reference to “Holocaust denier”; “uncertainty,” which is a scientific concept to convey variance or deviation from a specific value, but is interpreted by a lay audience to mean that scientists do not know the answer; and “consensus,” which is the process by which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) forms its position, but leads some in the public to believe that climate science is a matter of “opinion” rather than data and modeling.

Overall, the challenge becomes one of framing complex scientific issues in a language that a lay and highly politicized audience can hear. This becomes increasingly challenging when we address some inherently nonintuitive and complex aspects of climate modeling that are hard to explain, such as the importance of feedback loops, time delays, accumulations, and nonlinearities in dynamic systems.13 Unless scientists can accurately convey the nature of climate modeling, others in the social debate will alter their claims to fit their cultural or cognitive perceptions or satisfy their political interests.

Employ climate brokers | People are more likely to feel open to consider evidence when a recognized member of their cultural community presents it.14 Certainly, statements by former Vice President Al Gore and Sen. James Inhofe evoke visceral responses from individuals on either side of the partisan divide. But individuals with credibility on both sides of the debate can act as what I call climate brokers. Because a majority of Republicans do not believe the science of climate change, whereas a majority of Democrats do, the most effective broker would come from the political right. Climate brokers can include representatives from business, the religious community, the entertainment industry, the military, talk show hosts, and politicians who can frame climate change in language that will engage the audience to whom they most directly connect. When people hear about the need to address climate change from their church, synagogue, mosque, or temple, for example, they w ill connect the issue to their moral values. When they hear it from their business leaders and investment managers, they will connect it to their economic interests. And when they hear it from their military leaders, they will connect it to their interest in a safe and secure nation.

Recognize multiple referent groups | The presentation of information can be designed in a fashion that recognizes that individuals are members of multiple referent groups. The underlying frames employed in one cultural community may be at variance with the values dominant within the communities engaged in climate change debate. For example, although some may reject the science of climate change by perceiving the scientific review process to be corrupt as part of one cultural community, they also may recognize the legitimacy of the scientific process as members of other cultural communities (such as users of the modern health care system). Although someone may see the costs of fossil fuel reductions as too great and potentially damaging to the economy as members of one community, they also may see the value in reducing dependence on foreign oil as members of another community who value strong national defense. This frame incongruence emerged in the 2011 US Republican primary as candidate Jon Huntsman warned that Republicans risk becoming the “antiscience party” if they continue to reject the science on climate change. What Huntsman alluded to is that most Americans actually do trust the scientific process, even if they don’t fully understand it. (A 2004 National Science Foundation report found that two thirds of Americans do not clearly understand the scientific process.)

Employ events as leverage for change | Studies have found that most Americans believe that climate change will affect geographically and temporally distant people and places. But studies also have shown that people are more likely to believe in the science when they have an experience with extreme weather phenomena. This has led climate communicators to link climate change to major events, such as Hurricane Katrina, or to more recent floods in the American Midwest and Asia, as well as to droughts in Texas and Africa, to hurricanes along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico, and to snowstorms in Western states and New England. The cumulative body of weather evidence, reported by media outlets and linked to climate change, will increase the number of people who are concerned about the issue, see it as less uncertain, and feel more confident that we must take actions to mitigate its effects. For example, in explaining the recent increase in belief in climate change among Americans, the 2012 National Survey of American Public Opinion on Climate Change noted that “about half of Americans now point to observations of temperature changes and weather as the main reasons they believe global warming is taking place.”15

Ending Climate Science Wars

Will we see a social consensus on climate change? If beliefs about the existence of global warming are becoming more ideologically entrenched and gaps between conservatives and liberals are widening, the solution space for resolving the issue will collapse and the debate will be based on power and coercion. In such a scenario, domination by the science-based forces looks less likely than domination by the forces of skepticism, because the former has to “prove” its case while the latter merely needs to cast doubt. But such a polarized outcome is not a predetermined outcome. And if it were to form, it can be reversed.

Is there a reason to be hopeful? When looking for reasons to be hopeful about a social consensus on climate change, I look to public opinion changes around cigarette smoking and cancer. For years, the scientific community recognized that the preponderance of epidemiological and mechanistic data pointed to a link between the habit and the disease. And for years, the public rejected that conclusion. But through a process of political, economic, social, and legal debate over values and beliefs, a social consensus emerged. The general public now accepts that cigarettes cause cancer and governments have set policy to address this. Interestingly, two powerful forces that many see as obstacles to a comparable social consensus on climate change were overcome in the cigarette debate.

The first obstacle is the powerful lobby of industrial forces that can resist a social and political consensus. In the case of the cigarette debate, powerful economic interests mounted a campaign to obfuscate the scientific evidence and to block a social and political consensus. Tobacco companies created their own pro-tobacco science, but eventually the public health community overcame pro-tobacco scientists.

The second obstacle to convincing a skeptical public is the lack of a definitive statement by the scientific community about the future implications of climate change. The 2007 IPCC report states that “Human activities … are modifying the concentration of atmospheric constituents … that absorb or scatter radiant energy. … [M]ost of the observed warming over the last 50 years is very likely to have been due to the increase in greenhouse gas emissions.” Some point to the word “likely” to argue that scientists still don’t know and action in unwarranted. But science is not designed to provide a definitive smoking gun. Remember that the 1964 surgeon general’s report about the dangers of smoking was equally conditional. And even today, we cannot state with scientific certainty that smoking causes lung cancer. Like the global climate, the human body is too complex a system for absolute certainty. We can explain epidemiologically why a person could get cancer from cigarette smoking and statistically how that person will likely get cancer, but, as the surgeon general report explains, “statistical methods cannot establish proof of a causal relationship in an association [between cigarette smoking and lung cancer]. The causal significance of an association is a matter of judgment, which goes beyond any statement of statistical probability.” Yet the general public now accepts this causal linkage.

What will get us there? Although climate brokers are needed from all areas of society—from business, religion, military, and politics—one field in particular needs to become more engaged: the academic scientist and particularly the social scientist. Too much of the debate is dominated by the physical sciences in defining the problem and by economics in defining the solutions. Both fields focus heavily on the rational and quantitative treatments of the issue and fail to capture the behavioral and cultural aspects that explain why people accept or reject scientific evidence, analysis, and conclusions. But science is never socially or politically inert, and scientists have a duty to recognize its effect on society and to communicate that effect to society. Social scientists can help in this endeavor.

But the relative absence of the social sciences in the climate debate is driven by specific structural and institutional controls that channel research work away from empirical relevance. Social scientists limit involvement in such “outside” activities, because the underlying norms of what is considered legitimate and valuable research, as well as the overt incentives and reward structures within the academy, lead away from such endeavors. Tenure and promotion are based primarily on the publication of top-tier academic journal articles. This is the signal of merit and success. Any effort on any other endeavor is decidedly discouraged.

The role of the public intellectual has become an arcane and elusive option in today’s social sciences. Moreover, it is a difficult role to play. The academic rules are not clear and the public backlash can be uncomfortable; many of my colleagues and I are regular recipients of hostile e-mail messages and web-based attacks. But the lack of academic scientists in the public debate harms society by leaving out critical voices for informing and resolving the climate debate. There are signs, however, that this model of scholarly isolation is changing. Some leaders within the field have begun to call for more engagement within the public arena as a way to invigorate the discipline and underscore its investment in the defense of civil society. As members of society, all scientists have a responsibility to bring their expertise to the decision-making process. It is time for social scientists to accept this responsibility.

Notes

1 Wouter Poortinga et al., “Uncertain Climate: An Investigation into Public Skepticism

About Anthropogenic Climate Change,” Global Environmental Change, August 2011.

2 Aaron McCright and Riley Dunlap, “The Politicization of Climate Change and Polarization

in the American Public’s Views of Global Warming, 2001-2010,” The Sociological

Quarterly 52, 2011.

3 Clive Hamilton, “Why We Resist the Truth About Climate Change,” paper presented

to the Climate Controversies: Science and Politics conference, Brussels, Oct. 28, 2010.

4 Andrew Hoffman, “Talking Past Each Other? Cultural Framing of Skeptical and Convinced

Logics in the Climate Change Debate,” Organization & Environment 24(1), 2011.

5 Jon Krosnick and Bo MacInnis, “Frequent Viewers of Fox News Are Less Likely to

Accept Scientists’ Views of Global Warming,” Woods Institute for the Environment,

Stanford University, 2010.

6 Jeffrey Rachlinski, “The Psychology of Global Climate Change,” University of Illinois

Law Review 1, 2000.

7 Max Boykoff, “The Real Swindle,” Nature Climate Change, February 2008.

8 Ding Ding et al., “Support for Climate Policy and Societal Action Are Linked to Perceptions

About Scientific Agreement,” Nature Climate Change 1, 2011.

9 Matthew Feinberg and Robb Willer, “Apocalypse Soon? Dire Messages Reduce Belief in

Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs,” Psychological Science 22(1), 2011.

10 Thomas Vargish, “Why the Person Sitting Next to You Hates Limits to Growth,”

Technological Forecasting and Social Change 16, 1980.

11 Nick Mabey, Jay Gulledge, Bernard Finel, and Katherine Silverthorne, Degrees of Risk:

Defining a Risk Management Framework for Climate Security, Third Generation Environmentalism,

2011.

12 Jonathan Schuldt, Sara H. Konrath, and Norbert Schwarz, “‘Global Warming’ or

‘Climate Change’? Whether the Planet Is Warming Depends on Question Wording,”

Public Opinion Quarterly 75(1), 2011.

13 John Sterman, “Communicating Climate Change Risks in a Skeptical World,” Climatic

Change, 2011.

14 Dan Kahan, Hank Jenkins-Smith, and Donald Braman, “Cultural Cognition of Scientific

Consensus,” Journal of Risk Research 14, 2010.

15 Christopher Borick and Barry Rabe, “Fall 2011 National Survey of American Public

Opinion on Climate Change,” Brookings Institution, Issues in Governance Studies,

Report No. 45, Feb. 2012.

How small business and "green" business came hand-in-hand with eBay and Intuit.

How small business and "green" business came hand-in-hand with eBay and Intuit.

TCHO company executive John Kehoe talks about the firm's goals in producing high-end products and helping farmers in developing countries.

TCHO company executive John Kehoe talks about the firm's goals in producing high-end products and helping farmers in developing countries.

Buzz Thompson identifies models of collaboration across areas of expertise that can help us solve complex societal issues.

Buzz Thompson identifies models of collaboration across areas of expertise that can help us solve complex societal issues.

Business efforts must become more sustainable and responsible to turn the tide on social inequity and environmental decay. Net positive is a new standard that can help ensure a resilient and regenerative world.

Business efforts must become more sustainable and responsible to turn the tide on social inequity and environmental decay. Net positive is a new standard that can help ensure a resilient and regenerative world.

People, place, and the Pope offer new hope for environmental progress.

People, place, and the Pope offer new hope for environmental progress.

There is no scientific consensus on the safety of GMOs and no evidence that their commercialization has been beneficial to society as a whole; until there is, it is prudent to just say no.

There is no scientific consensus on the safety of GMOs and no evidence that their commercialization has been beneficial to society as a whole; until there is, it is prudent to just say no.

How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate focuses on the nuances of America's social psychology and cultural beliefs - and how those contexts shape the politics and readings of climate science.

How Culture Shapes the Climate Change Debate focuses on the nuances of America's social psychology and cultural beliefs - and how those contexts shape the politics and readings of climate science.

Before critiquing art that speaks to climate change, the scientific community must broaden its view on what art is and how it can help the movement.

Before critiquing art that speaks to climate change, the scientific community must broaden its view on what art is and how it can help the movement.

COMMENTS

BY Muja'hid AbdulBari,MS

ON August 17, 2012 05:45 PM

As I read your VERY erudite recount of your evangelizing encounter and subsequent research, I couldn’t help wondering whether today’s split in consciousness has its roots in the era when ‘ole Thomas Jefferson penned that oft repeated idea that ‘We hold these Truths to be self evident…” while he and his class were simultaneously the financial beneficiaries of 1) the enslavement of a large group of ‘Creator’ created men, women and children; 2) the theft of a continent by genocidal pressure against its native inhabitants and 3) the invalidation of his professed religious foundation through his personal bigamous relationship with the half sister of his legal wife. Somewhere he (‘ole TJ) is quoted as suspecting something like Divine retribution on some people for ALL that behavior. Diggers into the evidences of the past suggest that whole peoples have been suddenly destroyed for exactly the obstinate obtuseness that his looking has uncovered for him. It is, sadly for so many, the way of empires.

On the other hand, if Prof. Hoffman had every been a high achieving contact sport athlete, once he realized that he had been baited & set up, he might have inquired if the gladiator brain had ever been to Mt. Kilimanjaro or the Arctic region of the Polar Bears’ home. Some folks have to see it for themselves for the TRUTH to register. Al Gore??

BY Antony Berretti

ON August 19, 2012 12:26 AM

Dear Andrew.

Very good article and draws out the point about yes it’s happening, no it’s not argument.

I saw this years ago and gave up trying to persuade friends to modify there lifestyles in relation to the evidence that was even 30 years ago accumulating. Now over the past six years I tried a different approach, but to no avail, the vast majority of world citizens have been drugged with the concept of doubt.

You only have to look at the way the British colonialist empire dealt with any of it’s populace, even it’s own citizen during the Victorian period, to see how long this technique has been around for. Entice the people with a cheap and readily avail drug, such as opium, as history from the Opium wars of the 19th century taught us and you the authority or privileged ruling class, can do what you please, hiding behind religious script to justify your actions.

Today that opium takes the form of anything that can tie the population into a financial nose around their neck, so that you have no time to consider anything else, other than earning more to pay off what you owe or would like to acquire. Clearly there are things that are essential such as food, shelter, medicines or the ability to travel to work, but as people are tied into following social trends, they fall into this trap from which there is no escape unless you can, as you say, see the greater picture and understand where this will eventually take society.

Your current presidential election which I follow, as a Scot, I see events in the USA as central to decision making for all counties to which we should take a note of, I understand the importance of this up coming vote, so no surprise when republicans behave as opium drugged Chinese!

But I shall and hopefully you too will battle on as there is no future for any human being if we continue as nothing is wrong.

BY David L. Hagen

ON August 23, 2012 01:14 PM

Andrew

Thanks for grappling with the issues.

Two major problems in climate communication are caused by two equivocations:

“climate change” referring to recent global warming versus the natural changes over millions of years; and referring to major “anthropogenic global warming” versus natural CO2 changes dominating over minor anthropogenic contributions.

You presume that majority “science” is right and warming will be harmful.

However, the IPCC’s 0.2 C/decade mean warming prediction is running hotter than 95% of actual temperature trends (> 2 sigma) for the last 32 years of satellite data measurements. I.e. the red corrected OLS trend is 0.138 C/decade [0.083, 0.194]. See Lucia Liljegren, The Blackboard, etc. Recent evidence shows cloud trends could have caused most warming etc. Thus the current “consensus” appears to be an argument from authority or popularity that does not recognize that major physics is missing and that climate sensitivity (feedback) to CO2 has been strongly overestimated.

The strong benefit of CO2 to increasing food production will be very important for feeding the growing world population. Developing countries need fossil fuels to rise out of poverty. Pragmatically, we need to recognize their rapid increase in fossil fuels and that adaptation appears much more cost effective than “mitigation.” In the long run, we will need to transition to sustainable fuels, and use available fossil fuels in the transition.

For balancing views and information, see: The Copenhagen Consensus, The Cornwall Alliance, CO2 Science, and the Non-governmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC). PS The Bangladesh delta is rising with sea level because of Himalayan siltation.

BY Josee Allen

ON August 24, 2012 09:08 AM

If Global warming is the result of 200 years of industrial activity, and as we have now, by and large, cleaned up our industries, how can we prevent the newly industrialised nations from continuing the pollution? Also we have to stop the elitist politicians from using tax payers money and resources to “reward their friends and punish their enemies” when they give massive and corrupt contracts which seem to end up financing China’s industry, which is far from ‘clean’.

BY Alan Anderson

ON August 24, 2012 11:13 AM

As a midwestern farmer, I read with great interest Mr. Hoffman insightful article. Here on the farm (latitude 40.25n.), our growing seasons have been lenghtening and precipitation totals

increasing. On the surface this would appear to be a good thing,however the volatility that has accompanied these changes is problematic. From an agricultural point of view, it probably makes a big difference whether you are a farmer from north Texas or North Dakota as to how you view global warming/ climate change. There are always winners and losers with any kind of change and it seems to me that it is this reality that is seldom acknowledged. Thanks again for your thoughtful analysis.

BY Girma Orssengo

ON August 25, 2012 03:20 PM

To briefly summaries, as shown in the chart below, the AGW sand castle was built by smoothing the GMST oscillation before the 1970s, leaving the warming phase of this oscillation since then untouched, and calling this recent warming man-made.

http://bit.ly/OaemsT

BY Girma Orssengo

ON August 25, 2012 03:30 PM

Today, there is no doubt that a scientific consensus exists on the issue of climate change. Scientists have documented that anthropogenic sources of greenhouse gases are leading to a buildup in the atmosphere, which leads to a general warming of the global climate and an alteration in the statistical distribution of localized weather patterns over long periods of time.

That consensus was obtained by misinterpretation of the data by smoothing the GMST oscillation before the 1970s, leaving the warming phase of this oscillation since then untouched, and calling this recent warming man-made.

http://bit.ly/OaemsT

BY Girma

ON August 25, 2012 04:13 PM

And yet the physical impacts of climate change are already becoming visible in ways that are consistent with scientific modeling, particularly in Greenland, the Arctic, the Antarctic, and low-lying islands.

Not so.

For the USA, in the last 100 years data from NOAA, the most extreme drought occurred in the 1930s (Dust Bowl) and the extreme wet occurred in the 1970s.

http://www1.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/cmb/sotc/drought/2012/06/uspa-wet-dry-mod-ext-190001-201206.gif

BY Girma Orssengo

ON August 25, 2012 04:56 PM

Climate Science as Culture War

By Andrew J Hoffman

It is a very well written article that supports your position on what to do to stop man made Global Warming.

Enjoyed reading it.

However, I disagree with your position.

In the following chart, when you look at the global mean temperature data since record begun 162 years ago, there has not been any change in its pattern.

http://bit.ly/Aei4Nd

Its pattern has been on a slight warming trend since the little ice age.

BY Andrew Hoffman

ON August 26, 2012 09:56 AM

My goal in writing this article is to discuss the social and psychological processes that influence how we process complex scientific information. Overall, I believe that the kinds of value conflicts I describe are embedded within most, if not all, environmental and scientific/technology issues. I had dinner the other night with a medical ethicist who said he saw the same kinds of dynamics I describe in the question over home birthing. They are at play in the questions over environmental issues like whether to drill in ANWR, place restrictions on toxic chemicals like Bisphenol-A or protect endangered species. And they are at play on other scientific/technological questions like the installation of smart meters, the safety of nanotechnology or the question of a link between vaccinations and autism. In the end, the process by which scientists come to conclusions is far different than the process by which society comes to conclusions. Scientists and other interested parties need to recognize and not lament that fact. I have some scientists who feel that this direction of inquiry is a waste of time because it is a debate over “truth.” But, as I teach my MBA students, it is one thing to come up with what you think is the right answer. It is a totally different thing to convince people it is the right thing, and then get them to do something about it.

I appreciate the feedback I have received on this page and more directly. also recommend some very good work by Jonathan Haidt (The Happiness Hypothesis, and The Righteous Mind) on the topic.

BY Peter Erskine

ON August 26, 2012 03:30 PM

In the seventh paragraph of this article, Andrew Hoffman says “The answers to this question can be found, not from the physical sciences, but from the social science disciplines of psychology, sociology, anthropology, and others.”.

I would take issue with such an insulting assertion. The primary reason why there is such a large groundswell of questioning, is that the “warmists” have always hijacked the meeting and run off with the agenda before the results are in. In their eagerness to force early conclusions and to grasp the resulting funding, they sweep under the carpet the fact that there is still scientific climate research going on, and a far greater amount of general science research (not necessarily pure climate research) that still awaits to be done.

Society is only just at the beginning of collecting together the list of factors that affect climate; and our understanding of how, and how much, each factor affects climate is still rudimentary.

It is therefore 100% reasonable to object to the loud calling-out of premature and basically unsound conclusions.

And this has nothing to do with anthropology or psychology! It is simply rationalism and “good science”.

BY Joe Brewer

ON August 26, 2012 04:55 PM

Hello Andrew,

Thank you so much for writing this article. I left a Ph.D. program in atmospheric science nearly a decade ago to study human cognition and social values for this exact reason. It is profoundly important that the psychological and cultural drivers of these phenomena become better known.

Back in 2008, I co-authored a paper making the same argument you have presented here. It was published in the Environmental Law Review with the title “Why the Environmental Movement Needs a Cognitive Dimension.” You can download it here:

http://www.cognitivepolicyworks.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/EnvironmentalCognitivePolicy.pdf

I would love to speak with you about how our respective works can merge. This is an area of research and emerging practice that I have dedicated my life to. I have worked with many leading researchers and scholars across psychology, linguistics, anthropology, and neuroscience to build a cogent framework for cultural engagement that I’d love to explore with you.

Very best,

Joe Brewer

Director, Cognitive Policy Works

Seattle, WA

BY Richard J. Bono

ON August 27, 2012 08:08 AM

I am an architect living in York County Pennsylvania, across the Susquehanna from Lancaster County. I am co founder of a local land trust which is one of five in the two country region that makes us the #1 ag preservation region in the USA. Among our natural assets a extremely high quality soils combined with generally reliable and abundant rainfall. The UN has designed parts of our region as one of the three greatest naturally irrigated farming areas on the planet.

I…among many others here… have been attuned to the rhythms of nature with our ag tradition, and our strong local food movement. I have also followed the science of Climate Change as a non scientist….reading poplar books by James Hansen and Heidi Cullen. On occasion I have discovered what I had intuited to be true, had scientific support. In an ag area, attention to nature is not something abstract. It’s a matter of business. It’s a matter of both scientific and practical knowledge, it is a matter of politics…and it’s a matter of religion.

I agree with you whole heartedly, that speaking the cultural language of social group is central to moving public consciousness and education. Here, our strong ag preservation movement has caught the imaginations of many disparate groups, who have cooperated to make it happen…from businessmen, to small farmers, to production farmers, to politicians, to bankers, to lawyers, etc. Central to this fact, as corny (sorry) as it might sound, is the idea that the good society is one that values the stewardship of the land. The idea of stewardship is both Biblical AND a scientific one. However if this sense was the only value, our success would have never materialized.

The practical and economic mechanism for stewardship and conservation is legal instrument called the conservation easement. Here landowners GIVE UP development rights to their land. Under any of our five programs, the difference between the development value, and the agricultural value, serves as the basis, of either a direct state subsidy (through cigarette taxes), or a Federal income tax credit. This is something wealthy landowners, small farmers, production farmers, organic farmers, politicians, businessmen, lawyers, etc…all support, as evidenced by their presence on the boards of directors of these non profits. Here, easements can be tailored to different individual economic situations.

We have found a way to integrate many disparate interests, into a soundly based economic system that preserves our agricultural (and natural land) tradition…that is very consistent with the religious idea of stewardship. “Brokers”, as you call them, from many persuasions, were indeed employed to explain and popularize, within groups appropriate to their own experience of life.. Among the most effective with the most powerful elements here, surprisingly to some, were many of the lawyers…..and one architect.

Land preservation is so strong a value here now, that any politician who runs on a platform opposing farm and and natural land preservation will be soundly defeated…as forcefully demonstrated 20 years ago, in very Republican Lancaster.

But there are challenges ahead:

In regard to the dynamic nature of Climate Change, one incident comes to mind. I had heard that our plant hardiness zone was expected to change from a 6 to a 9 (or even 10) in 75 years. Such a change would have a profound impact, not only on the natural environment, but upon our agriculture, and hence our whole human community. I spoke to Dr. Richard Alley, member of the US Academy of Sciences, and Greenland ice core scientist…when he made a presentation to an auditorium full of students at York College, a business oriented school here. Dr. Alley confirmed pretty much what I had heard…saying: “that sounds about right.”.

When you mention existential threats to human society, it’s hard to imagine a more universal and geo-historic one. It also strikes me that those who live and work close to nature, as in places like York and Lancaster, will know from their everyday experience, that something important is changing. This is even more so in the areas of the country that will feel physical changes faster…like the American mid and south west, Florida. I suspect that continuing extreme weather events will eventually make a pure denier position untenable. It will become akin to denying the nose on one’s face.

If that was all there was to this I would be more hopeful, for the other element is time. Dr. Hansen says that we have 8 centuries of heat built into the earth system already. So reducing carbon dioxide, and improving our performance, might not really be enough in itself. He and Dr. Alley also speak of tipping points, and the seven major “positive feedback loops”, that no one knows how much “forcing” will activate. Alley’s science demonstrates is that quite catastrophic changes to the earth climate, occurred, quite often, and most alarmingly, abruptly….as 20 foot ocean rises within 8 years. This would realize Hansen’s “different planet” warning.

Dr. Alley says no one can predict such tipping point scenarios, but there is a clear element of existential risk involved. My point is that this is very serious business..and nature will not take into account the human timetable in realizing its peril. There is not an unlimited amount of time.

As one, now in the alarmist camp, I think your article could not be more important. We have to get started. Thank you.

BY Paul

ON August 27, 2012 12:36 PM

@ Girma

Have you added together, for each year, both tails of the distribution (unusually wet plus unusually dry) and then calculated a moving average for this data to look for a trend? I would think you could draw a more robust conclusion by doing so rather than visually identifying spikes in the data.

BY Paul

ON August 27, 2012 12:39 PM

Very insightful article by the way.

BY srp

ON August 28, 2012 05:22 PM

A propos of the article’s theme about appealing to the values of those whom one wants to persuade, I have long been baffled as to why Urgent Mitigationists (my own coinage intended to be more neutral than “alarmists”) have not unified behind a program of greatly increased nuclear power production. James Hansen has advocated this, but the movement in general has clustered behind the twin solutions of 1) massive cutbacks in energy use and 2) “soft” energy sources such as windmills, solar photovoltaics, and biofuels.

There are three reasons related to the theme of this article why this two-pronged approach taken by the UM movement is perverse and counterproductive. First, nuclear power, while more expensive per kilowatt-hour than fossil-fuel sources of electric power, is vastly cheaper than wind or solar, especially when adjusted for availability, reliability, need for backup sources, etc. Studious avoidance of what should be a natural call for expansion of the next-best source of electricity after fossil fuels breeds suspicion among typical American business/engineering types that the agenda of the UMs is not to solve an environmental problem but rather to pursue an ideological green deindustrialization agenda.

Second, nuclear power, as a quintessential “hard” technology, appeals to the Promethean and cornucopian values of pro-capitalism, pro-technology constituencies that are heavily represented among skeptics. Nobody will hear a call for expanded nuclear capacity as some sort of conspiracy by Gaia-worshipping anti-growth fanatics to make us all live as peasants. Rather than a step back from progress it will be perceived as a confirmation of the progressive track of technological civilization. Windmills and solar, by contrast, beyond their economic and technical weaknesses, smack of exactly the kind of call for passivity and surrender to natural forces that many on the political right see as anti-civilizational.

Third, vigorous advocacy of nukes would lend huge credibility to those claiming the mantle of science because it would run contrary to the persistent fear mongering about radiation and nuclear safety promulgated by self-described environmentalists. It’s hard to take seriously people who say that their views are driven by the scientific consensus reported by official bodies when those same people reject the “settled science” behind the risks of radiation, deaths per kilowatt-hour across technologies, the safety of waste disposal and/or reprocessing, etc. In this regard, Urgent Mitigationists ought to have raised a massive hue and cry about the recent decisions by both Germany and Japan to cut back or eliminate nuclear power from their generating bases; their failure to do so again casts suspicion that their real allegiances are to a sentimental nature-worship rather than a pragmatic response to climate risks.

BY Stephen Scanlon

ON August 28, 2012 07:04 PM

Your use of “logic schism” has filled a lexicographical void for me. It might go a long way to explain why the justices of the Supreme Court can so often come up with those 5 - 4 decisions. If they are approaching an issue from distinct perspectives, how can they be expected to reference the same body of the law in their interpretations. This is the same when people are talking at cross purposes when they have no basis for understanding one another. Logic schism is a failure to be able to understand the other. Entering the enemy’s camp - the social scientist’‘s job - is sometimes necessary and a sign of crossing into understanding is that one leaves the camp somewhat humbled. That is why those on the extremes cannot be effective leaders.

BY Richard J. Bono

ON August 29, 2012 06:31 AM

In my earlier comment, I badly erred when I wrote that James Hansen said that there are eight centuries of heat already in the earth system. I meant to say eight centuries to dissipate antropogenic carbon dioxide.

BY Uday Bhaskar

ON September 13, 2012 08:35 PM

Dear Andrew,

thanks for a very elaborate and detailed article. however, i think this is one of the reasons why people get averse on this issue, as we generate more verbal gibberish than making crisp and factual points. the title is attractive enough, but the points made are very stretched and all encompassing so that we get rounded by all commercial propaganda that shapes everything what we call (very loosely) our culture. We do not need to go very far than check our facts in daily life, the catch is to do that by consciously avoiding traps of commercial propaganda. If we do that we directly appreciate the truth of the matter, be it science, culture, etc.. surrounding the climate change. and more importantly, to talk of crisp point, I would say the concern now on should be described more as ‘human change’ than climate change, because we are causing this change, not nature. If we get this point, without letting our bloated egos coming in the way, we will do good for ourselves and the nature, as always can take care of itself.

thanks

uday

BY Robert Cavalier

ON October 10, 2012 06:02 AM

It is important to realize that the principles and practices of deliberative democracy can help to diagnose the problems involved in discussing climate change as well as to provide solutions to the challenge of discussing climate change. Two centers whose work is informed by the social sciences are the Center for Deliberative Democracy at Stanford ( http://cdd.stanford.edu ) and the Program for Deliberative Democracy at Carnegie Mellon ( http://hss.cmu.edu/pdd/ ). Both centers have been actively involved with citizen deliberation.

Recently, the Program for Deliberative Democracy hosted a series of Campus Conversations on Climate Change - See

http://www.cmu.edu/homepage/environment/2012/fall/climate-change-conversation.shtml

and http://hss.cmu.edu/pdd/polls/climate/campus/pgh.html

BY Eli Rabett

ON November 12, 2012 07:22 PM

You make a fundamental mistake in your analogy with the tobacco issue, the tobacco companies were forced to admit the link to lung cancer and other life shortening illnesses in court as the price for being allowed to stay in business. It was not the result of some nebulous public health community’s efforts, but rather plaintiff’s lawyers and state attorney generals jumping on them long after the scientific case was clear.

Your argument fails because what your “donor” and the fossil fuel interests and the Homeland Institutes and the CATO Institute and the Girmas are looking for is affirmation that they should be taken seriously. They should not, and doing so only delays action.

Your argument is not new, it has never worked and unfortunately it is not working today. While confrontation may be polite, it is strenuous even when so, but unfortunately it is necessary.

BY Gail Zawacki

ON November 27, 2012 11:12 AM

Dear Professor Hoffman,

I actually did attend a Heartland Conference (uninvited!) because I wanted to understand what enables professional deniers to be so convincing. (original blog post and photos here: http://witsendnj.blogspot.com/2011/07/beware-banality-of-evil-heartless-at.html)

One of the first questions asked by a speaker was, let’s suppose burning gas and oil and coal IS bad. What are we going to replace it with? Solar panels? Wind? Geothermal?

This elicited guffaws in the audience and therein, I believe, lies the simple answer. Deniers don’t believe that “renewable” (to the extent it really is renewable, because it isn’t since it is produced with many nonrenewable resources) can ever replace the concentrated power of fossil fuels. And they’re right.

Most climate activists and scientists have no answer for this other than “faith” in technological magic - rather than confronting head-on that in order to make even a dent in the acceleration of global warming, thanks to all those amplifying feedbacks, the developed nations would have to sacrifice by drastically curtailing consumption…and the developing nations would have to drastically curtail population.

Nothing less will do, and as long as the Big Gang Green organizations pretend we will be saved by recycling, and buying local, and giving them donations, the deniers suspect quite rightly that there is no credibility in the environmental movement, and this is what enables them to dismiss the science.

To use your analogy of tobacco use - people had to QUIT. And they had to be tremendously frightened by an existential threat to do so.

BY peter kenneth

ON December 28, 2012 11:30 PM

Thank you for penning down such a great thought. I think there is a need to take initiative in order to save our earth.

BY nursing ceu

ON February 1, 2013 09:06 PM

Very insightful post, Thank you so much for writing this article and sharing your thought to save our earth.

BY bill from Arizona

ON March 29, 2013 03:07 PM

This is an interesting subject. I was intrigued how you mentioned someone who evangelized you in the beginning of your article then in the first paragraph of the second section you evangelized to your readers.

I’ll admit that I am a skeptic. I have a strong science background and believe I can identify fuzzy science when it is presented. There are too many questions on cause and effect, tampering with the data, and bullying by the climate science elites. Why does no one in the climate science field call out Al Gore’s false claim of CO2 to temperature correlation in the ice core record? Or when “climategate” broke out and the wagons were circled. When these scientists idly sit back and not condemn these kinds of behavior they show they are not “critical” of their own science.

The IPCC itself is not a scientific body, but rather a political body. The term “denier” is a way to bully people, even though those that do not goose step to the IPCC come in many flavors. And yes there are many top climatologists that think the IPCC is not representative of the science.

However, the bigger question is that you might want to consider your own beliefs and why you believe them before trying to change the minds of others.

BY Richard

ON September 25, 2013 08:18 PM

I think your post does show some totalitarian tendecies and in addition tendecies for hatred for capitalism and personal immorality and generally far leftism and being part of the cultural divide. As well as hypocricy and dihonesty and a want to mislead people and lack of open mindedness.

AGW is also true by the way.

I ask that you actually examine your own beliefs and whether there are any limitations to them. Maybe upsetting the status quo too much without putting certain boundaries in place could cause more harm than good, social change of great sacrifice that you call necessary (bassically you are a cousin to communists) might come with greater negative consequences than moving forward with capitalistic technological and otherwise inovvations than the impossible goals.

Indeed some of the most misanthropic ecologist enviromentalist visions are more extreme than communism too but that does not mean we should not have any enviromentalism in general. The problem is you keep the door half open to them instead of closed shut in that message of your, showing deep irresponsibility just like Einstein did (you are no Einstein) when he praised the communist regimes of his time.

BY aed939

ON April 7, 2014 04:04 PM

It might be helpful to examine some retrospectful hypotheticals. Rather than trying to model the future, consider whether the world would be better off or worse off if we had the preindustrial atmospheric CO2 levels. What would crop yields be? W ould we be able to feed 7 billion people? How much land would be devoted to agriculture? What would the world ecosystems be—would there be less diversity and more extinctions? Would it be less green? Would there be slower reforestation?

BY Brad Keyes

ON April 19, 2014 03:10 PM

Andrew,

the reason this debate so stimulates and puzzles you, and the reason you’re on the wrong “side” of it, is that you don’t understand HOW SCIENCE WORKS. You can’t even tell pseudoscience from science.

For example:

> Today, there is no doubt that a scientific consensus exists on the issue of climate change.

Consensus in science is meaningless.

It’s got an evidentiary value of zero. Why are you even talking about a “consensus” on a matter of nature?

Oh, that’s right. Because climate science, as a movement, is PSEUDOscientific.

If you had a science PhD you’d know this. It’s not exactly hard to spot when you know what you’re looking for!

> Both the US National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science use the word “consensus” when describing the state of climate science.

It’s almost like they’re TRYING to tell you it’s pseudoscience.

> And yet a social consensus on climate change does not exist.

Maybe the general public knows more about HOW SCIENCE WORKS than you, Andrew. Ever think of that possibility?

> Surveys show that the American public’s belief in the science of climate change

“belief in the science of…”

Gibberish.

In science the object of belief, disbelief, knowledge, doubt, etc. is the HYPOTHESIS (which may become a THEORY in time). A human being can’t believe or deny something called “the science.” That isn’t English. What do you even picture in your head when you say that?

> Belief declined from 71 percent to 57 percent between April 2008 and October 2009, according to an October 2009 Pew Research Center poll;

Belief IN WHAT?

“The science”? Word salad.

“Climate change”? An unfalsifiable, undefined, uninteresting platitude. EVERYONE believes in climate change, even the people so sick of hearing about it that they tick the “Dismissive” box in the hope people on your “side” will shut up about it.

> beliefs that emerge, not from individual preferences, but from societal norms;

Can you name any other belief about how nature works that arises from “societal norms”? I was under the impression they arose from science books.

> Why is this so? Why do such large numbers of Americans reject the consensus of the scientific community?

You mean the climate-scientific community, and the answer is:

— consensus isn’t worth one iota of evidence, so why SHOULD people agree with it?

— any scientific community that has consensus researchers like Oreskes and Cook… isn’t one. It’s a pathological, post-scientific wasteland. Consensus is meaningless, so why is anyone studying it?

Oh, that’s right: to get rhetorical ammunition for the “Culture War.”

> With upwards of two-thirds of Americans not clearly understanding science or the scientific process

Including “science communicators” like yourself, Andrew!

Sad, isn’t it?

And their understanding is only getting worse the longer you allow them to think “peer review” and “consensus” are scientific concepts. Well done. You’re creating a generation of scientific illiterates.

> How do people interpret and validate the opinions of the scientific community?

How do they USUALLY do that?

Think about it. The answer’s in front of your face.

> To understand the processes by which a social consensus can emerge on climate change, we must understand that people’s opinions on this and other complex scientific issues are based on their prior ideological preferences, personal experience, and values

That’s true, in the absence of an understanding of how science works—a kind of herd/tribe thinking takes over and people align with others like them.

Those of us who know how science works aren’t polarized though.

> “...that the effects of global warming have already begun ...”

Sorry but what is that clause trying to say?

Try putting it in the form of a falsifiable hypothesis if you want buy-in from those of us who know how to have a scientific debate.

> the debate will take the form of what I call a “logic schism,” a breakdown in debate in which opposing sides are talking about completely different cultural issues.4

That’s already happening, but the opposing “sides” aren’t Liberal and Conservative.

They’re the sides identified by CP Snow and Alan Sokal.

Read them and you’ll know why your sentences don’t look like English to me.

> When analyzing complex scientific information, people are “boundedly rational,” to use Nobel Memorial Prize economist Herbert Simon’s phrase;