Carbon Capture and Sequestration

Adsorption and membrane processes are investigated for carbon capture applications. Breakthrough and isotherm experiments are carried out on carbon-based sorbents to investigate the kinetics and material capacities. Simulations using Grand Canonical Monte Carlo are carried out to assist in sorbent design (pore structure and chemistry). Similar models are used to investigate gas (CO2, methane, water) transport in nanoporous systems of coal and gas shale rocks. Nitrogen-selective membrane technology is also investigated for carbon capture.

Topic 1. Breakthrough Experiments

Figure 1. Experimental apparatus for combustion flue gas breakthrough experiments.

The reactor may be heated using controlled tube furnace, creating the ability to perform temperature swing adsorption (TSA) experiments and test the capacity and attrition rate of the sample over multiple cycles, as well as determine the heat of regeneration. The CO2 uptake (and release) are measured using a custom-built Extrel quadropole mass spectrometer (MS). The MS is positioned at the outlet of the packed-bed reactor to determine breakthough time.

The CEC lab is also equipped with a Rubotherm microbalance for carrying out adsorption experiments and a Quantachrome instrument to characterize sorbents based on argon, CO2 and N2 adsorption experiments.

Funding Source: GCEP

Topic 2. Gas Sorption Modeling Using Grand Canonical Monte Carlo

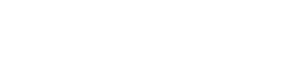

The implementation of the GCMC method yields the adsorption isotherms of a given adsorbent-adsorbate interaction in micro- and meso-slit pores: the total and the excess adsorption isotherms are predicted and the effects of pore size and surface functionality investigated. Total adsorption represents the total amount of CO2 adsorbed per unit pore volume, including CO2 in both condensed surface-bound adsorbed phase and weakly surface-bound gas phases. The excess adsorption is the additional amount of CO2 adsorbed per unit pore volume compared with the amount of CO2 in the same volume as the pore without the pore walls. The conversion from total to excess adsorption bridges the molecular simulation results to the direct experiment measurements.

Figure 2. Comparison of the simulated adsorption isotherm with the experimental measurement at 305 K.

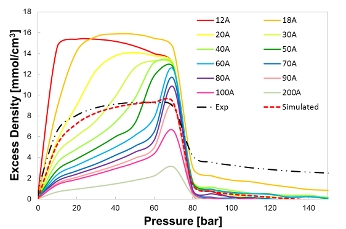

Figure 3. Functionalized graphitic surfaces investigated in the current work. These functional groups are positioned in the center of the top layer of the periodic graphite slabs.

Figure 4. Comparison of the pore volumes with different surface functionalities.

Funding Source: BP

Topic 3. Transport Model Predictions using Molecular Dynamics

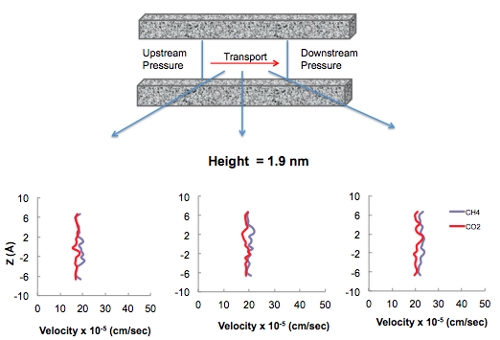

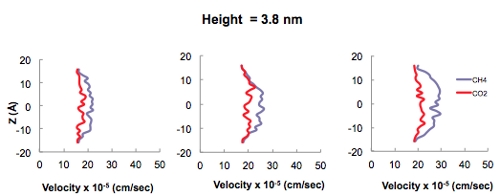

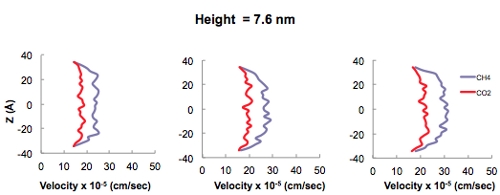

In addition to the adsorption isotherm predictions, transport of CO2 and methane as a function of pore diameter using MD simulations also leads to interesting results associated with gas transport in nanoporous materials. These simulations are carried out in an attempt to determine at which pore size the fluid-wall interactions vs purely fluid-fluid interactions become important in terms of playing a role in the mechanism of fluid transport in systems comprised of nanopores. The Klinkenberg effect is a result of gas slippage along the walls of a pore, in which fluid-wall interactions dominate over fluid-fluid interactions and may occur when the pore diameter approaches the mean free path of the gas. Conveniently, MD simulations are carried out to determine at which pore diameter this effect becomes pronounced. Figure 5 shows the velocity profiles of pure CO2 and CH4 fluids in 1.9, 3.8, and 7.6-nm sized pores. As the pore size increases it is evident that fluid-fluid interactions dominate resulting in the familiar Hagen-Poiseuille flow vs. the plug-flow behavior in smaller pores (i.e., pore diameter of 1.9 nm) where fluid-wall interactions dominate in the Knudsen regime. The transition between these two flow regimes occurs somewhere in the neighborhoof of 4 nm. Therefore, since both micro (i.e., < 2 nm) and mesopores exist in earth systems such as coal and gas shales, a combination of these two transport mechanisms is expected to occur.

Figure 5. Velocity profiles of pure CO2 and CH4 in 1.9, 3.8, and 7.6 nm sized carbon slit pores exhibiting the relevance of the fluid-wall interactions at smaller pore sizes.

Funding Source: DOE-NETL

Topic 4. Nitrogen-Selective Membranes (Post-combustion capture)

The US has over 300 GW of power capacity from pulverized coal combustion. Reducing emissions from coal will require postcombustion capture technology to retrofit these existing power plants. This capacity, representative of approximately 50% of all power generated in the US is responsible for more than 30% of annual CO2 emissions . Currently amine scrubbing is the technology of choice for postcombustion capture of CO2 due to it being a proven technology for smaller-scale applications of current market production of CO2. This technology comes with its challenges and still has not been proven to be successful on the scale of carbon capture required of the current US coal fleet.

The CO2 concentration in the flue gas of pulverized coal combustion is too small of a driving force to take advantage of a membrane technology for selective CO2 capture. The proposed research aims at applying dense membrane technology to take advantage of the nitrogen (N2) driving force in postcombustion capture.

The membrane housing would ideally be connected directly after the boiler or after the SCR (selective catalytic reduction) catalyst used for NOx reduction if one is in place . Since the NOx reduction process produces additional N2 the membrane technology could be placed after this unit so that the evolved gas is removed.

Figure 6. Schematic of N-Selective Membrane Reactor

Funding Sources: ARO (DURIP); NSF (Catalysis)