A 1950s Approach to 21st Century Issues

The tariffs discussion is important but distracts from confronting other pressing economic issues.

President Donald Trump listens as Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven speaks during a news conference in the East Room of the White House in Washington, Tuesday, March 6, 2018. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh) The Associated Press

The news as cable TV spectacle was in overdrive Tuesday evening: A porn star suing President Donald Trump consuming CNN, the lingering punditry on MSNBC about an apparently-inebriated former Trump aide's erratic ways and two Fox News pundits engaging in ad hominem personal attacks against one another before frustrated host Laura Ingraham bid them both a hasty farewell.

Whew. And, then, there was also the matter of tariffs and world economic stability.

It's why Trump, our ardent Mar-a-Lago populist, is now at least apt course material for Emily Blanchard, an expert in international economics and public policy at Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business. Yes, he's grist for the mill of a pointy-head in the bucolic Ivy League enfolds of New Hampshire (which he'd probably privately love to know) due to tariffs, not Stormy Daniels.

"I've told students it doesn't add up," she says as Trump's well chronicled warnings of tariffs on imported steel and aluminum inspire rebuke and European admonitions of counter-measures against U.S. bourbon (hello, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky) and Harley Davidsons (sorry, House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin), among other prideful red-white-and-blue products on its politically-predictable retaliation list.

She spoke on a day in which Gary Cohn, Trump's top economic aide, disclosed he was splitting, clearly frustrated with the president. As introduction, I mentioned to Blanchard how I once covered organized labor and chronicled calamitous declines in the auto, steel and other industries starting in the late 1970s.

I knew the pulse of and the best joints in towns and hoods that never recovered even amid the astonishing rise of other sectors and Croesus-like wealth across America. There were the tales of families cast aside. Of losers who never rebounded amid American transformation. Of those who now can't imagine possessing a MacBook Air or other symbol of a post-Rust Belt economy, who fear children's cavities they can't afford to fill.

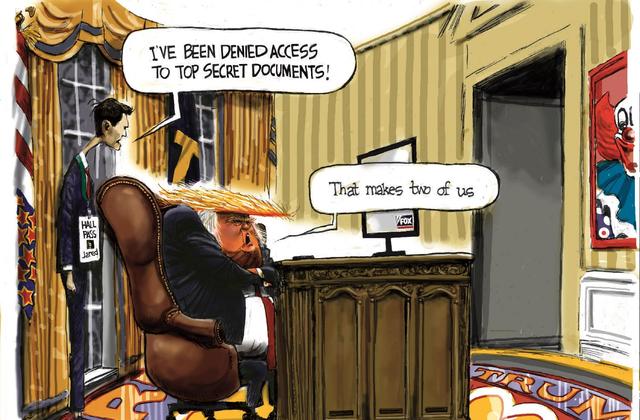

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

For sure, the debate inspired by Trump shows a notable free trade consensus that's built over several decades among the society's elites. But there's also a myopia over inequality and frayed social cohesion. The current public debate, no surprise, is not always rife with nuance, which is why I asked Blanchard initially about larger realities she feels might be missed.

In her mind, there is first the reality of trade being about comparative advantage and how everything possesses an opportunity cost. Increasing employment in steel and aluminum is fine, she says, but then tell her what we'd then not be making. Want to increase manufacturing? What sectors do you shrink? Where do all the workers come from for the cars you may want to roll off of assembly lines?

The second most important thing is that the trade deficit is what we think it is: It is not about exports and competitiveness. "This derives me bananas," she says. The either-or construct that permeates at least some of the recent discussion is unartful. It misses realities about the relevance of trade through longer periods of time, as well as some facts that relate to buying and selling assets.

The United States is nifty at producing things and offering a lot of growth possibilities, she says. And many investors worldwide would love to own some share of our economy, whether it's shares of Google stock, Treasury bills or even a fancy home somewhere.

But what people forget is that our open capital markets mean that we are selling assets. Simply put, the rest of the world buys our assets. The trade deficit is what happens when the world is selling us more stuff precisely because they are buying some of our assets. They help fund Apple and Google and the same municipal debt that builds our bridges, or funds kids' educations if a family is borrowing.

"When we say let's get rid of the trade deficit, we are saying let's stop borrowing from rest of world or, equivalently, let's no longer have rest of the world invest in the U.S.," she says. That, she underscores, is a rather different conversation whose ramifications are profound and maybe not well understood.

Don't want that deficit and, thus, investment from afar? Watch interest rates rise, fewer bridges get built or not as many kids winding up in college or trade schools. "That's what we mean when we say, 'shrink the deficit,'" she notes.

So don't just pick out a company or an industry, take a mercantilist perspective and declare that the battle involves our company against somebody else's. It misses how we are borrowing and lending with the rest of the world.

And so, we have the current situation over tariffs, which includes the fantasy of some citizens that other nations won't retaliate in rapid kind. "No, no, no," she says. Everybody loses. If the European Union turns its back on our cranberries, motorcycles, bourbon, orange juice, soybeans and rice, it's not good at all.

Blanchard doesn't really look at the Trump threats in a political context. That's not her metier. She doesn't know about power plays inside the White House beyond the obvious: Trump is displaying views articulated on the campaign trail that are consistent with a zero-sum game analysis. That means viewing trade through the lens of competitiveness and not discerning what she deems a needed larger equilibrium in the economy.

That takes us back to how making more steel may well mean not making more of something else. I think of the long-shuttered U.S. Steel South Works on Chicago's South Side, which once had 25,000 workers and was an engine of upward mobility, especially for many immigrants throughout the 20th century. Long gone, the area never revived, its forgotten handiwork found in famous structures like the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

Blanchard mentions both Trump and Peter Navarro, the trade adviser little known until now and one of the reasons Cohn is departing. She strains to be diplomatic. "The economics are not sound," she says. They don't see how the many pieces of a complex society fit together. Of how, for example, interest rates depend on the openness of trade and capital markets. "It's hard to get the mind around but trade deficits are trade through time," she says.

Trade through time?

As she notes again, the world craves various American products. That's good, since that foreign investment keeps borrowing costs low and funds lots of things around us: corporate research and development, path-breaking innovation, infrastructure such as new or repaired bridges and road, as well as education. There's much more.

But to get their hands on such assets, the world exports more goods and services to the U.S. than it imports from the U.S. "Essentially, it's as if the rest of the world is saying 'Hey, we want to invest in the US – we want to buy a stake in the future of the U.S. economy' and in return, that influx for foreign investment means that the U.S. can import more goods and services today than it exports," she emails. "This is an accounting identity – it has to be true – if the rest of the world is (on net) investing in the U.S. (i.e. if the U.S. is running a capital account surplus), then the U.S. must run a current account deficit."

Now if you decided, as a matter of policy, to force all that trade to roughly balance, then net inflows of foreign investment will decrease, maybe sharply. "U.S borrowing costs would rise, which would cause investment, consumption, and (almost certainly) GDP to fall," she says. "Moreover, we'd spend much more of our taxes paying off existing government debt."

It's what she tries to underscore to students. It's balance of payments accounting at a national level.

And, yet, she remains sensitive to those citizens to whom I alluded earlier, the ones left behind. If a few dropped by a Dartmouth classroom, she says, "I would apologize."

Their frustrations have been ignored for far too long, including by her own profession. The effects of trade and technology were not fully perceived. There was a view that was, in hindsight at least, wishful thinking about the winners somehow compensating the losers.

"That is not happening," she observes, raising fundamental questions of what we do now. The view coursing through some of the pro-Trump reactions, and they exist on multiple levels, is that just a slight rewinding of the clocks might bring a more equitable income distribution.

Political Cartoons on the Economy

"But we can't go back even if we wanted to," she maintains. It would mean reducing the size of the larger pie and, also, mythologizing a past that wasn't all that grand (as a woman, she knows well the gender inequities in the marketplace of old). As Doug Irwin, a Blanchard colleague at Dartmouth whom I tracked down in New Zealand, puts it, "Trump is a 1950s guy who thinks we should produce a lot of coal, cars and steel with a lot of men employed."

Raising tariffs won't bring us back to some golden era. It forgets how technology will supplant bodies and robots will be responsible for much of any increased output (automation is a topic continually overlooked by Trump both as candidate and president). Look around any workplace and see how more is done with fewer. As is noted frequently, we are actually talking about precious few steel and aluminum jobs to be gained via tariffs, a small slice of the jobs to be lost if the rest of the world stops buying our stuff.

She asks for an important national conversation that, for sure, will be difficult in a world of Twitter driven-discourse with declining civic engagement and even arguable mounting media illiteracy (just read Robert Mueller's recent indictment of Russians for campaign skullduggery to see how they laughed at our inability to discern their fake news). And feverish immersion in what's "hot," like the pretty pedestrian 15 minutes on Stormy Daniels' lawsuit that opened a CNN prime-time show Tuesday evening.

How do we make work more valuable and better target our labor force? And it can't just be a factory-by-factory, town-by-town discussion. It's got to be big and broad and cohesive. The tariffs discussion is important but also a distraction from our confronting issues of education, infrastructure and related issues and policies.

"We need to have a really deep conversation about the value of our individual efforts and work, by everyone."

Trump, the born-to-the-manor New Yorker, has never experienced it himself. But the pain he exploits is indeed real.

James Warren, Contributing Editor for Opinion

James Warren is a contributing editor at U.S. News & World Report and an award winning reporter... READ MORE »James Warren is a contributing editor at U.S. News & World Report and an award winning reporter, columnist and editor. He is chief media writer for the Poynter Institute for Media Studies. He was managing editor of The Chicago Tribune and Washington bureau chief for both The Tribune and New York Daily News. He's been a regular commentator on CNN, MSNBC, Fox News and Al-Jazeera America. He was a Chicago columnist for The New York Times and has written for Vanity Fair, Politico, Washington Monthly, Time, The Atlantic, Daily Beast and Huffington Post. Follow him on twitter at @jimwarren55.

Tags: Donald Trump, trade, international trade, exports, imports

Recommended

Don't Blame Video Games

David ZendleMarch 8, 2018

The Medicaid Freeloader Fallacy

Rachel GravesMarch 8, 2018

Now We're Talking

Michael H. Fuchs March 8, 2018

Wave? What Wave?

Peter RoffMarch 7, 2018

Boots on the Ground in Schools

Nat Malkus March 7, 2018