TEHRAN — As another day of defiance, concessions and ominous threats transfixed Iran’s capital, it was increasingly apparent on Thursday that there was no clear path out of a deepening confrontation that has posed the most serious challenge to the Islamic republic in its 30-year history.

Multimedia

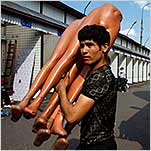

The situation had all the hallmarks of a standoff. Hundreds of thousands of silent protesters flooded into the streets. They roared a welcome to their champion, Mir Hussein Moussavi, the opposition candidate for president whose reported defeat by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in Friday’s election touched off the crisis.

Iran’s leaders offered conciliation, while simultaneously wielding repression.

With one hand, the government offered to talk to the opposition, inviting the three losing presidential candidates to meet with the powerful Guardian Council. While that reflected a continuing retreat from the initial insistence by Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, that the election results were accurate, many Iranians saw the offer as an effort to buy time and shield the ayatollah from public accountability. The Guardian Council is loyal to him.

Even Mr. Ahmadinejad, who has kept a defiant if low profile, made an unusual public concession. After insulting the huge crowds that poured into the street by dismissing them as “dust,” the president issued a statement on state television, according to The Associated Press:

“I only addressed those who made riot, set fires and attacked people. Every single Iranian is valuable. The government is at everyone’s service. We like everyone.”

With the other hand, the government continued to arrest prominent reformers, limit Internet access and pressure reporters to stay off the streets, and security officials signaled their waning tolerance.

It was not clear whether Iran’s government, made up of fractious power centers, was pursuing a calculated strategy or if the moves reflected internal disagreements, or even uncertainty.

“Most analysts believe the outreach is just to kill time and extend this while they search for a solution, although there doesn’t seem to be any,” said a political analyst in Tehran, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal. “This will only be a postponement of the inevitable, which is indeed a brutal crackdown.”

Important clues could emerge Friday, when Ayatollah Khamenei is scheduled to lead the national prayer service from Tehran University. Political analysts said that they hope that the leader will reveal his ultimate intent, indicating a willingness either to appease the opposition, or to demand an end to protests.

There was some speculation among Iran experts in the United States of a possible compromise, with reformers being given positions in a new government. But it was unclear if that would be acceptable to the opposition, which understands that in Iran, positions do not necessarily come with power. For eight years, the reform president, Mohammad Khatami, saw his program stifled by the conservative interests of the religious leadership and its allies.

“There could have been a very easy political solution, and that would have been nullifying the election results, but they have refused to do that so far,” said Mashalah Shamsolvaezin, a political analyst in Tehran. “Postponing the resolution means they want the military to find the solutions,” he said, referring to the Revolutionary Guards, not the army.

On Thursday the opposition remained firm in its demand for a new election, and it was not immediately clear how it would respond to the council’s offer of talks, which could take place as early as Saturday. The meeting would include Mr. Moussavi and two other candidates, Mehdi Karroubi and Mohsen Rezai.

Mr. Moussavi has indicated in the past that he does not trust the Guardian Council because some of its members campaigned on behalf of Mr. Ahmadinejad before the election. State radio said the Guardian Council had begun a “careful examination” of 646 complaints about the vote.

Nor was it clear what role was being played by a former Iranian president, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who supported Mr. Moussavi and is in a power struggle with Ayatollah Khamenei. Today there were unconfirmed reports that two of his children had been banned from leaving the country because of their role in helping the protesters.

The path to resolution is so cloudy because Iran’s political system is not based on coalitions or compromise. It has evolved into a winner-take-all contest, with each side holding competing views of what kind of country Iran should be: one in continuing opposition to the West, where individual freedoms are tightly restricted, or one more open to engagement with the world and greater civil liberties.

“We don’t have a consensus on who we are,” said a political scientist with close ties to Iran’s leadership. “Here we have ideology and ways of thinking that have nothing in common.”

In Iran’s theocracy, the supreme leader has vast power over the military, the judiciary and broadcasting. He also appoints 6 of the 12 jurists on the Guardian Council, which oversees Parliament and certifies election results, and so he exerts a profound influence on the organization.

The president and Parliament are elected by the people, and in recent years, popular demands have grown for social freedoms and economic gains. That pressure was easier to resist with Mr. Ahmadinejad as president, because it meant that conservatives controlled all the levers of power.

- 1

- 2