TEHRAN — The direct confrontation over Iran’s presidential election was effectively silenced Friday when the main opposition leader said he would seek permits for any future protests, an influential cleric suggested that leaders of the demonstrations could be executed, and the council responsible for validating the election repeated its declaration that there were no major irregularities.

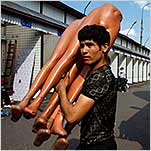

Ahmad Khatami, a senior Iranian cleric, delivered a sermon during Friday prayers in Tehran. More Photos »

Follow the latest updates on The Timesís news blog.

Go to the Lede Blog ĽBehind the Protests, Social Upheaval in Iran

What social forces have been unleashed in the aftermath of the disputed election in Iran?

What social forces have been unleashed in the aftermath of the disputed election in Iran?

Multimedia

Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, in front of a crowd, suggested at Friday Prayer in Tehran that protest leaders could be executed. More Photos >

Rather than address the underlying issues that led to the most sustained, unexpected challenge to the leadership since the 1979 revolution, the government pressed its effort to recast the entire conflict not as an internal dispute that brought millions of Iranians into the streets, but as one between Iran and outside agents from Europe, the United States and even Saudi Arabia.

It was a narrative that spoke both to the leadership’s belief that it had beaten back the popular outburst, and to the fragility of the calm. “There has been too much violence to forget about it,” said an expatriate Iranian analyst who is not being identified because he has relatives in Iran and is afraid of reprisals against them.

Although the government appeared to have the upper hand, political analysts said it was too soon for President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to declare his troubles over. Though it seemed increasingly likely he would be sworn in for a second term by early August, there was no guarantee how that term would unfold or whether competitors within the system — who have a different vision of Iran — would work against him.

Even before he faced a challenge to his legitimacy, Mr. Ahmadinejad was often castigated by Parliament for his troubled handling of the economy, and there had been talk of trying to impeach him. Several of his ministers quit the government in protest over his economic policies. “There are quite a few people sitting on the fence watching to see which way the wind will blow,” said Ali M. Ansari, a professor of Iranian history at St. Andrews University in Scotland. “Information is very hard to come by, but there seems to be much back-room negotiating predicated on the fact normality should first return to the country.”

Throughout the crisis, events in Iran have focused on two camps: the opposition, led by Mir Hussein Moussavi, a former prime minister, and the camp surrounding Mr. Ahmadinejad, including the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the military and security agencies. But there is a third group of more pragmatic military and security figures who have competed with Mr. Ahmadinejad but are believed to remain close to Ayatollah Khamenei.

Two of the most influential in that group are the mayor of Tehran, Mohammad Baqer Ghalibaf, a former commander in the Revolutionary Guards, and the speaker of Parliament, Ali Larijani, the nation’s former chief nuclear negotiator. Both ran for president four years ago and want to run again, and have at times been sharp critics of Mr. Ahmadinejad’s stewardship. Political analysts have described them as loyal to the leader and committed to Islamic government, but eager for a more modern state integrated with the rest of the world. Mr. Larijani resigned as nuclear negotiator in part because he favored engagement over confrontation.

During the electoral crisis both made statements demonstrating their independence from Mr. Ahmadinejad — and their objection to some aspects of the crackdown. The mayor called for allowing legal protests. The speaker said that it was improper for the Guardian Council, which is supposed to monitor the elections, to side with Mr. Ahmadinejad. Mr. Larijani also said that the majority of the people did not believe the government’s contention that Mr. Ahmadinejad had won with 63 percent of the vote.

“It’s an odd dynamic,” said Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The person they have to be loyal to, the supreme leader, has thrown his weight behind this person they despise. Ghalibaf is one of these people, like Larijani, and others had been on the fence, and if there is a tipping point they could go the other way.”

The government continued to try to frame any opponents as traitors to the nation. The Friday Prayer ceremony is a political and religious ritual held in a large hall at Tehran University and broadcast all over the country. Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, a stout, turbaned cleric who frequently delivers the Friday speech, hewed to the hard party line. He urged that those who led protests be convicted for taking up arms against people, an offense punishable by death.

“I want the judiciary to punish leading rioters firmly and without showing any mercy to teach everyone a lesson,” he said.

A few hours earlier, the Guardian Council repeated its claim that the election had been fair. “There has been no fraud in the election,” said the council’s spokesman, Abbas-Ali Kadkhodaei, acknowledging that the review process was not technically completed. He said the council had checked discrepancies reported by Mr. Moussavi, but that they had not borne out.

Mr. Moussavi immediately posted a report containing a long list of irregularities on his Web site, an action that barely registered against the might of the state machine. But he also signaled that the street phase of the protests was ending, saying on his Web site that he would try to seek permits for future protests — permits the government has consistently refused.

While protesters were aided at first by technology — primarily the Internet and text messaging — the government deployed its control of state television and news outlets to sweep away competing narratives.

“It is still possible that the information age will crack authoritarian structures in Iran,” wrote Jon B. Alterman, director of the Middle East program for the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “But it is far more likely that the government will be able to use that technology to secure its own rule.”

Mr. Moussavi may have little room to maneuver, but he has refused to surrender altogether. He is being closely monitored by security agents. Members of Parliament who are aligned with Ayatollah Khamenei met with Mr. Moussavi on Wednesday and tried to press him to relent.

“Mr. Moussavi still wants the election results nullified,” Ismail Kossari, one of the members of Parliament, told the ILNA news agency.

“We told him that his demand was unreasonable and immoral and he shouldn’t have repeated his demand after the supreme leader’s statements at the Friday prayers,” Mr. Kossari was quoted as saying.